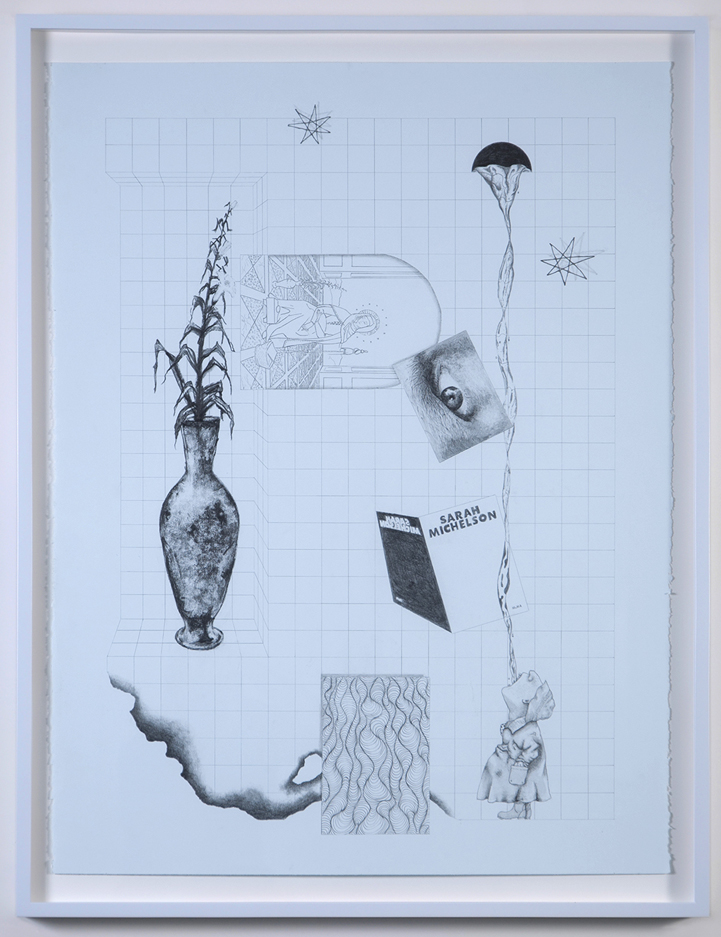

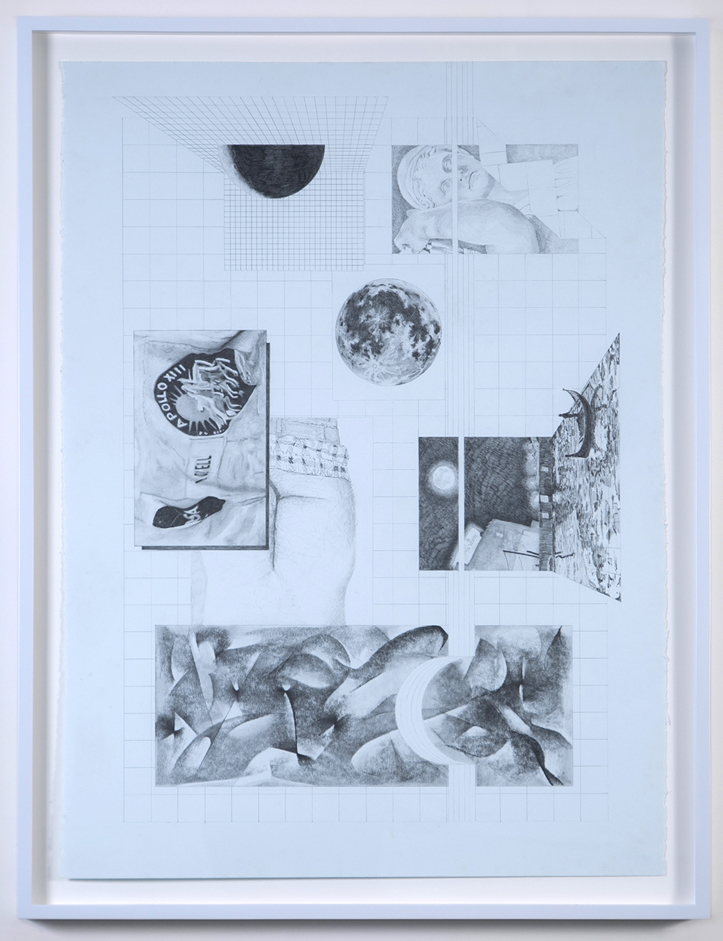

Artwork by Sam Roeck

New pencil drawings and space-design on view at OCDChinatown

Advent by Sam Roeck is on view through Oct. 3rd

Chinatown is underrated. But there lay energy uncharted. On a damp Monday in September (the humidity was still trying it) I walked over with the rest of the office to check out Sam Roeck’s show up at OCDChinatown. The address brought us to an indoor bizarre home to several shops and produce stands. Sure, we thought, it’s here?

OCDChinatown promotes itself as a clubhouse for queers, gays and women in performance, sound, word, film, fashion and “most of all kunst.” OCDChinatown is a set, a screen, an informal testing ground for new work. So when it came time to exhibit Sam’s latest work, the space was a bit of a no-brainer.

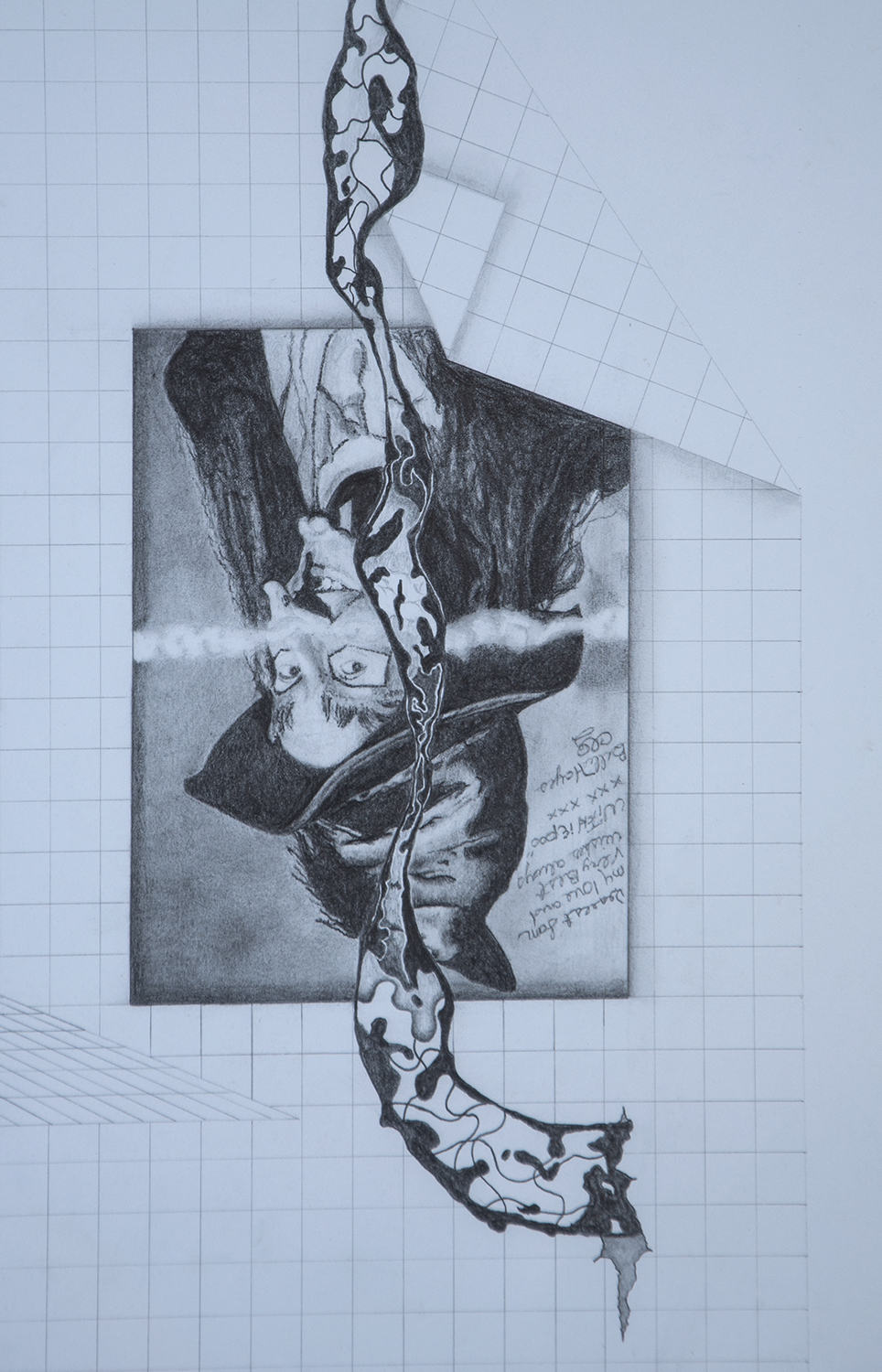

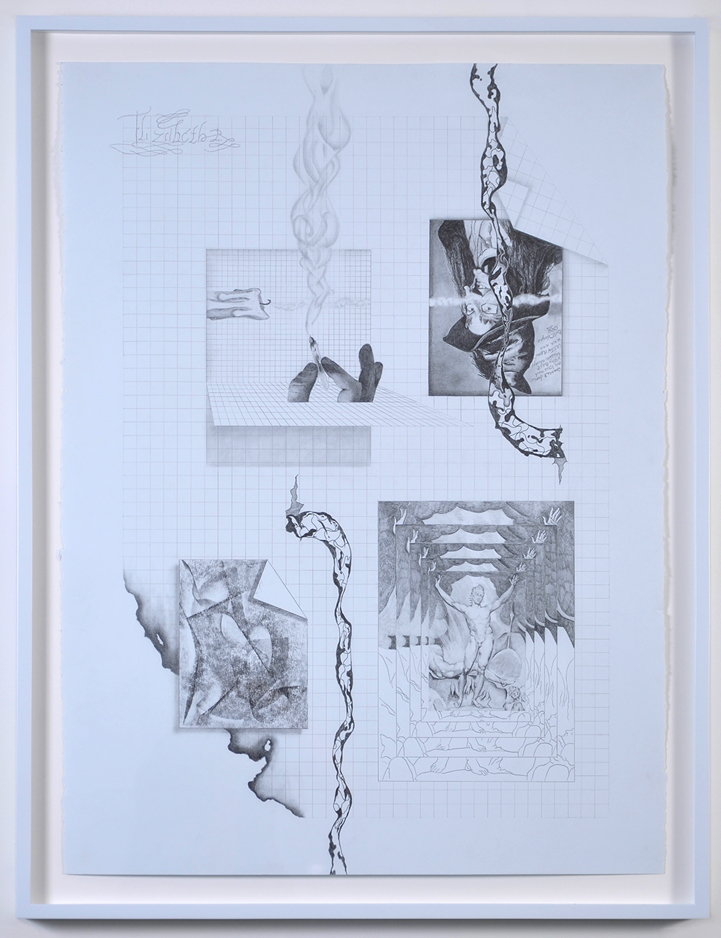

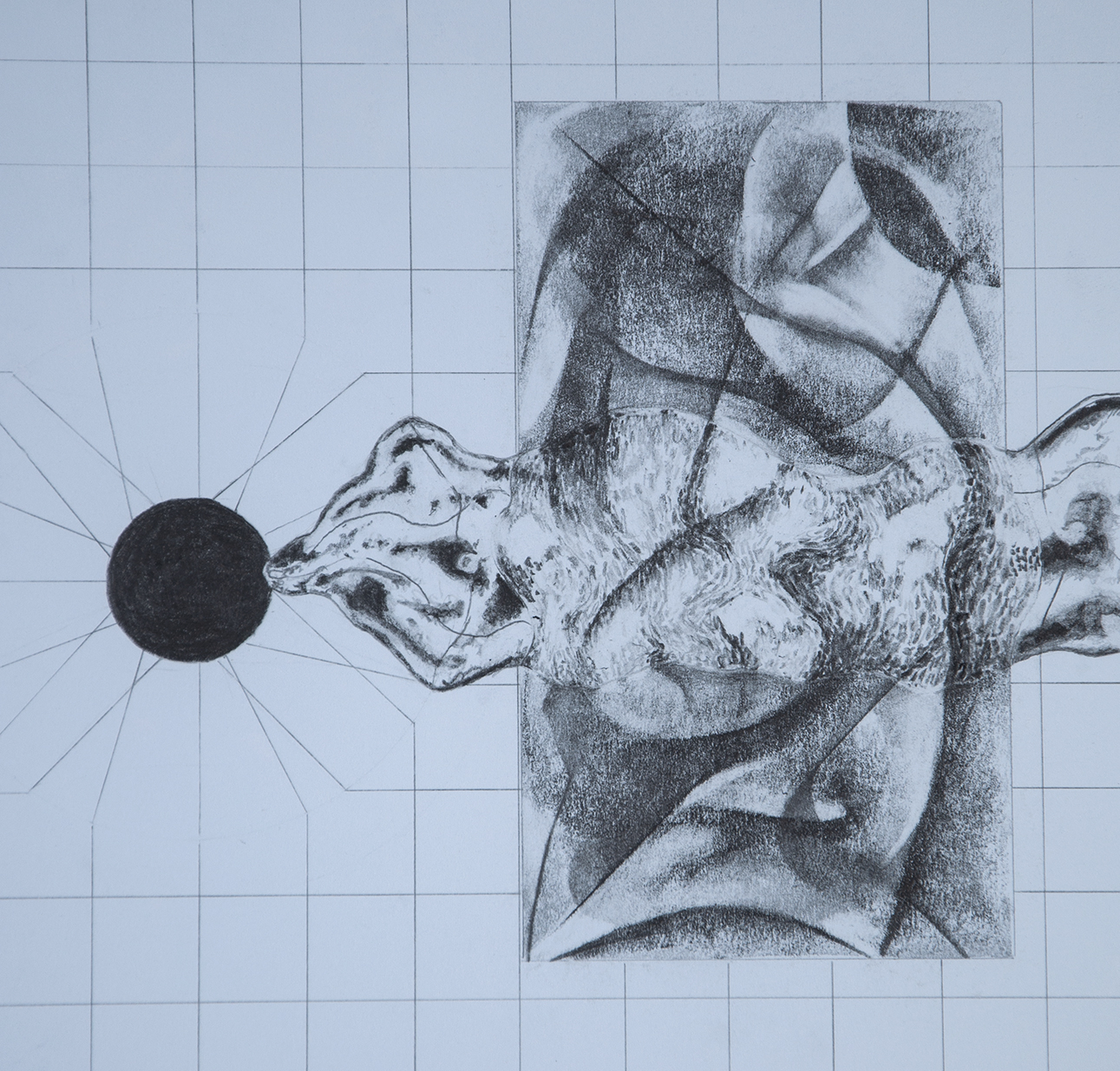

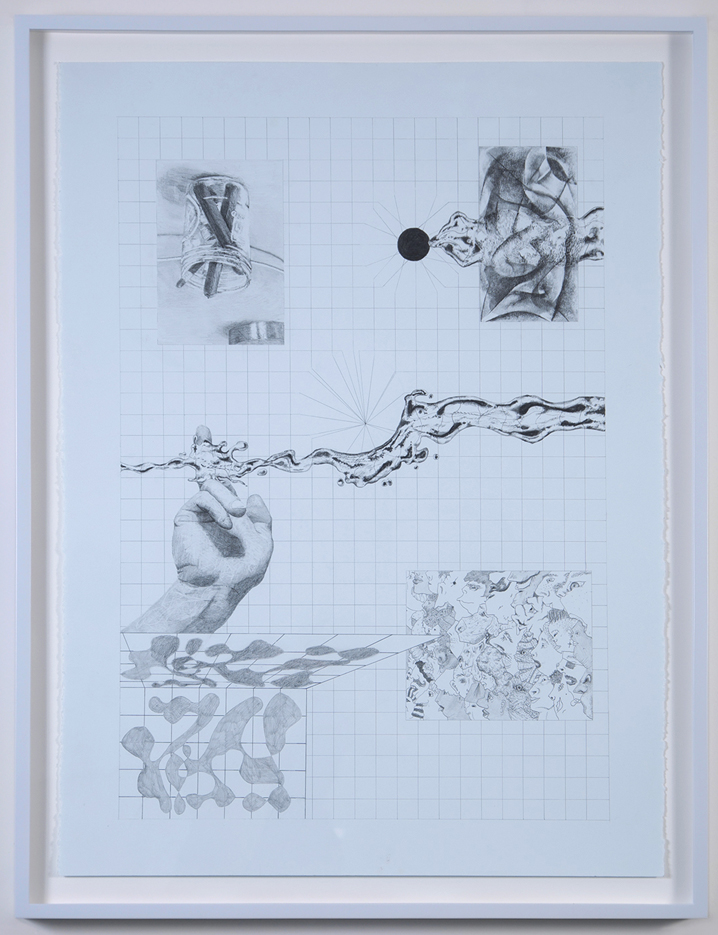

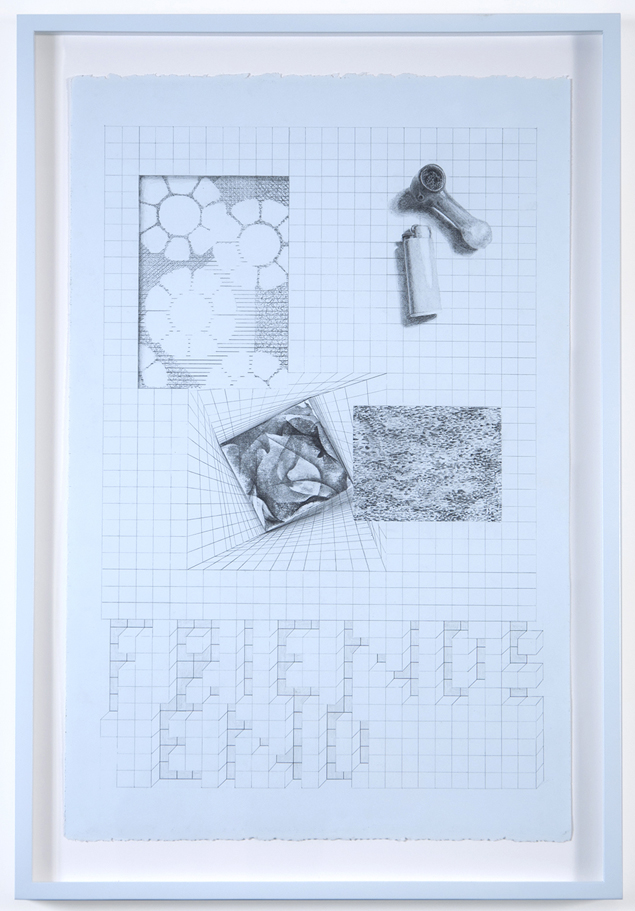

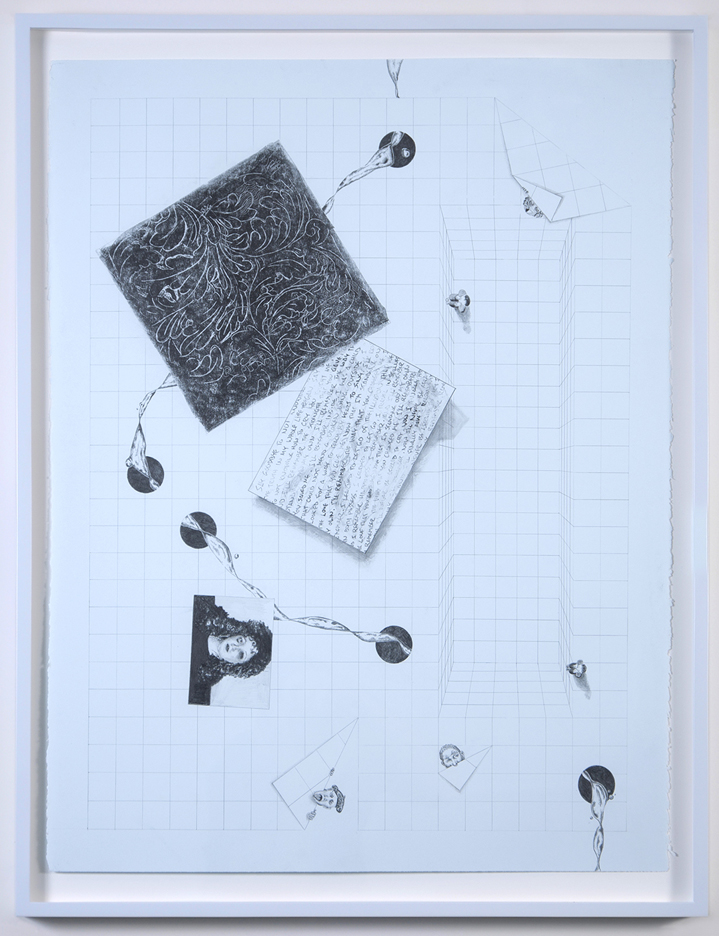

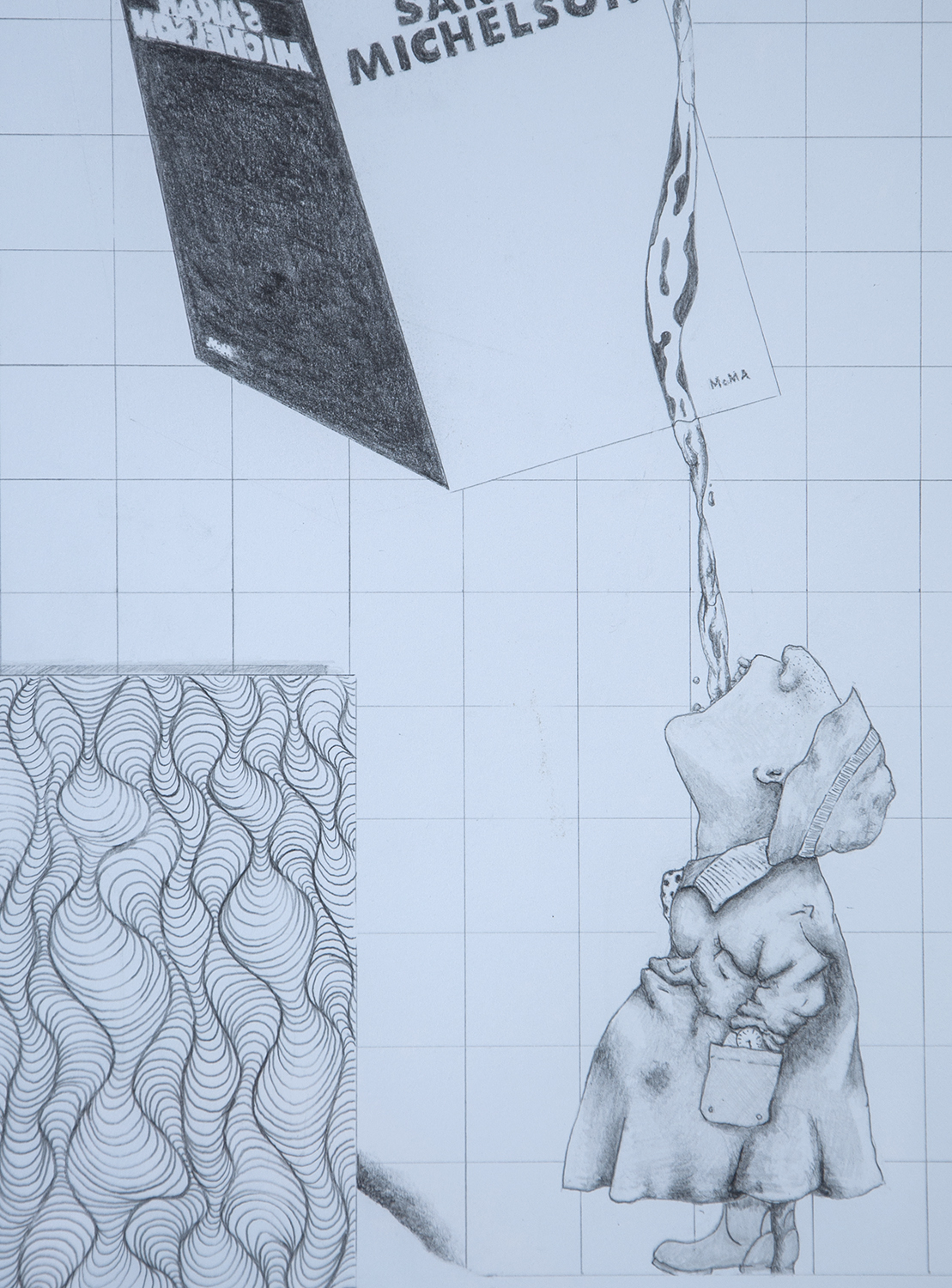

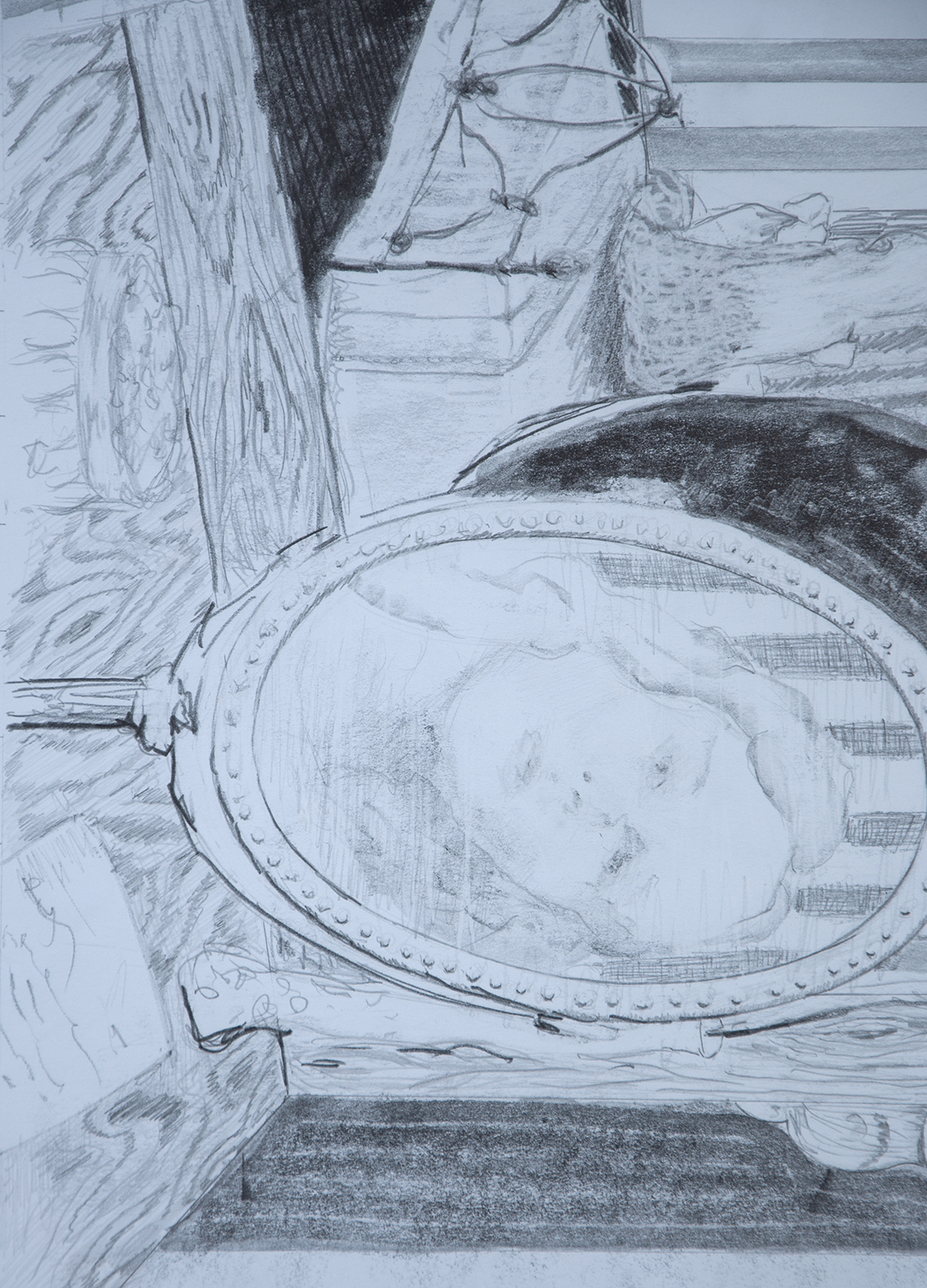

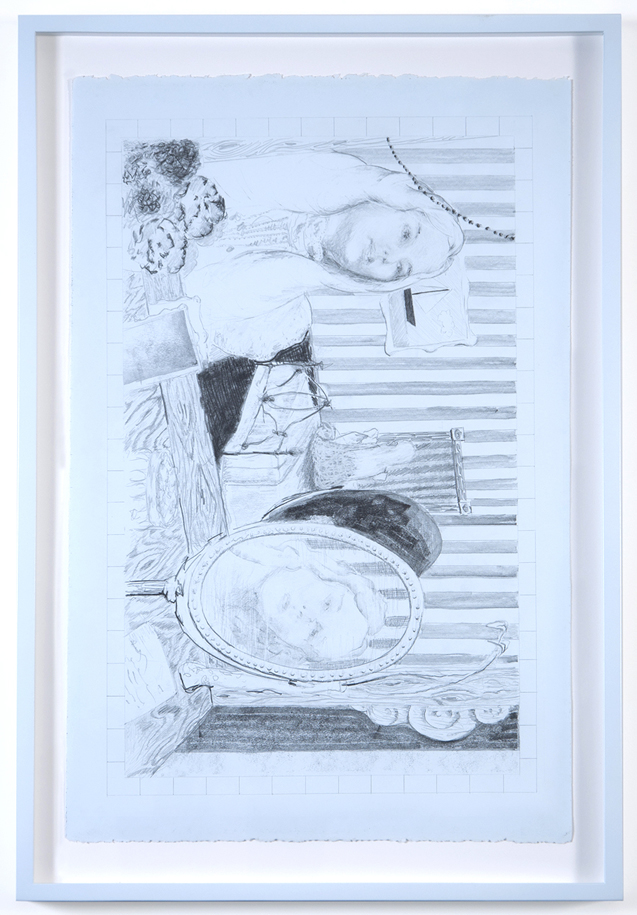

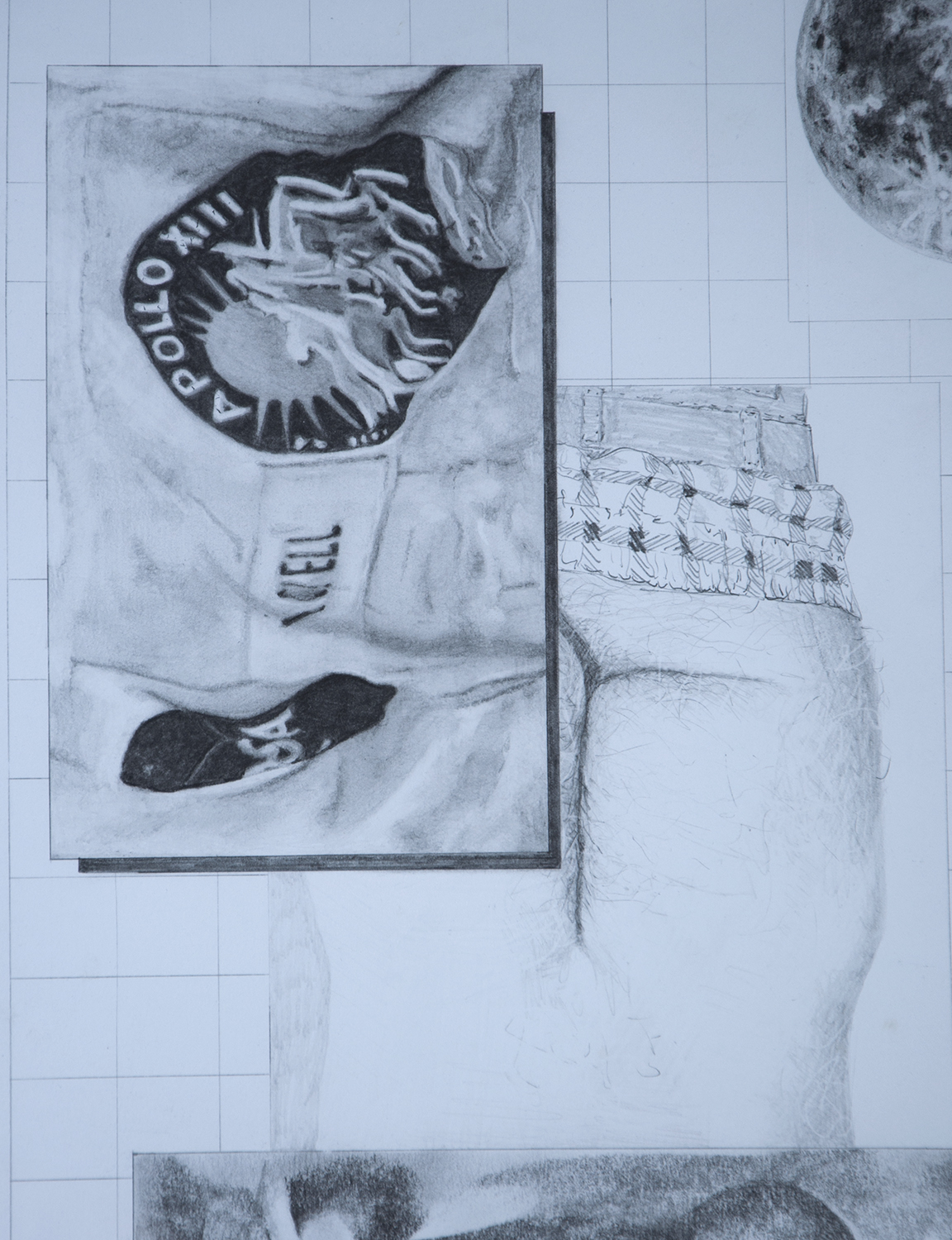

Working with pencil, Sam’s created six new drawings that operate on the grid, but his lines jettison off for right angles and protrude focus for subsequent eye tricks. Hallucinogenic-trails of liquid also help this visual-shtick, as well as exquisitely shadowed burnt edges. Sam’s hand is quite impressive, especially when you consider the total precision of the drawing and his cleanliness on page. The line-work itself takes immense concentration, and I wasn’t bothered by any kind of eraser marks. Besides, they make for great texture. But his drawings keep the eye skipping, much like watching pop-rocks, so I wasn’t searching for mistake, only the next best moment.

Having had no real context prior to going to the show, “Advent” is a formal presentation in a totally random space. I sent Sam some questions over email (he said he loves nothing more!) to hear more about the work and his approach to commercialism in art.

When did you start creating these works on paper, and how did you discern this as a show as opposed to stand-alone pieces? I started making these drawings about 18 months ago. As for them being stand-alone pieces or a show — can’t they be both? They all grew up together and now they are at this party in Chinatown and after that’s over they’re spreading out around the city and some are leaving the state. I made them knowing they would live apart from one another so there are things drawn into them that will always tie them together. Like how your mom used to write your name in your underwear in case you got lost.

Could you talk us through the process of creating these drawings? Some of them are very planned out and some kind of fall together. Some are specifically about things like a friend break-up and the moon, and some are more like how monks used to copy manuscripts and fill the margins with little drawings and dirty jokes to entertain themselves as they worked.

I have no idea how long they take individually. I’ll work on one and then stop and work on another. I listen to books on tape when I work and I know I went through nine books while working on this show, but some of them I listened to more than once.

I work hard at trying to keep the paper as clean as possible. I wash my hands a lot and use lots of cover sheets. I wanted the drawings to be a place where a dirty thumbprint or a poorly erased mark could live as an element of the drawing just as much as everything else in it. Isolating that space between chance and intention is really important to me.

Are you looking at process of making the works on paper any differently than your sculpture? Sculptures are real so they have to physically work and, like, stand up. It’s so nice that drawings don’t have that problem. But you have to draw things so that other people can see with your eyes. So on the one hand you are freed from the material world but on the other you have to spend a lot of time pretending to be a different person looking at what you just drew and seeing if they can see it the way you see it.

How do you go about selecting the popular-imagery that gets included into the drawings? Like why Nan Goldin, for example, and why that witch? I like that this question implies that the other imagery in the drawings is unpopular.

It’s less a selection process than a balancing act — like something super-personal weighted against a drawing of an abstraction plus a black hole that is sucking everything into it. Everything should make a mark on every level of consciousness. If you read Phillip Pullman’s description of how an alethiometer works- that is maybe the best description for how the images come together. Most important: I like them (or sometimes don’t, but in a way that I know is important for me).

The Nan Goldin portrait (“Nan One Month After Being Battered”) is in there because when I made that piece I had recently left my job in Nan’s studio and I felt really conflicted about that decision to leave. That particular portrait is a really complicated piece for me. I love it, but it’s also fucked up to love it and drawing it — taking the time to really sit with that piece and reproduce it in this slow manner — felt devotional and cathartic, a way of relating to this trauma that’s both hers and that she also made everyone’s, which is a relationship to trauma I can learn from.

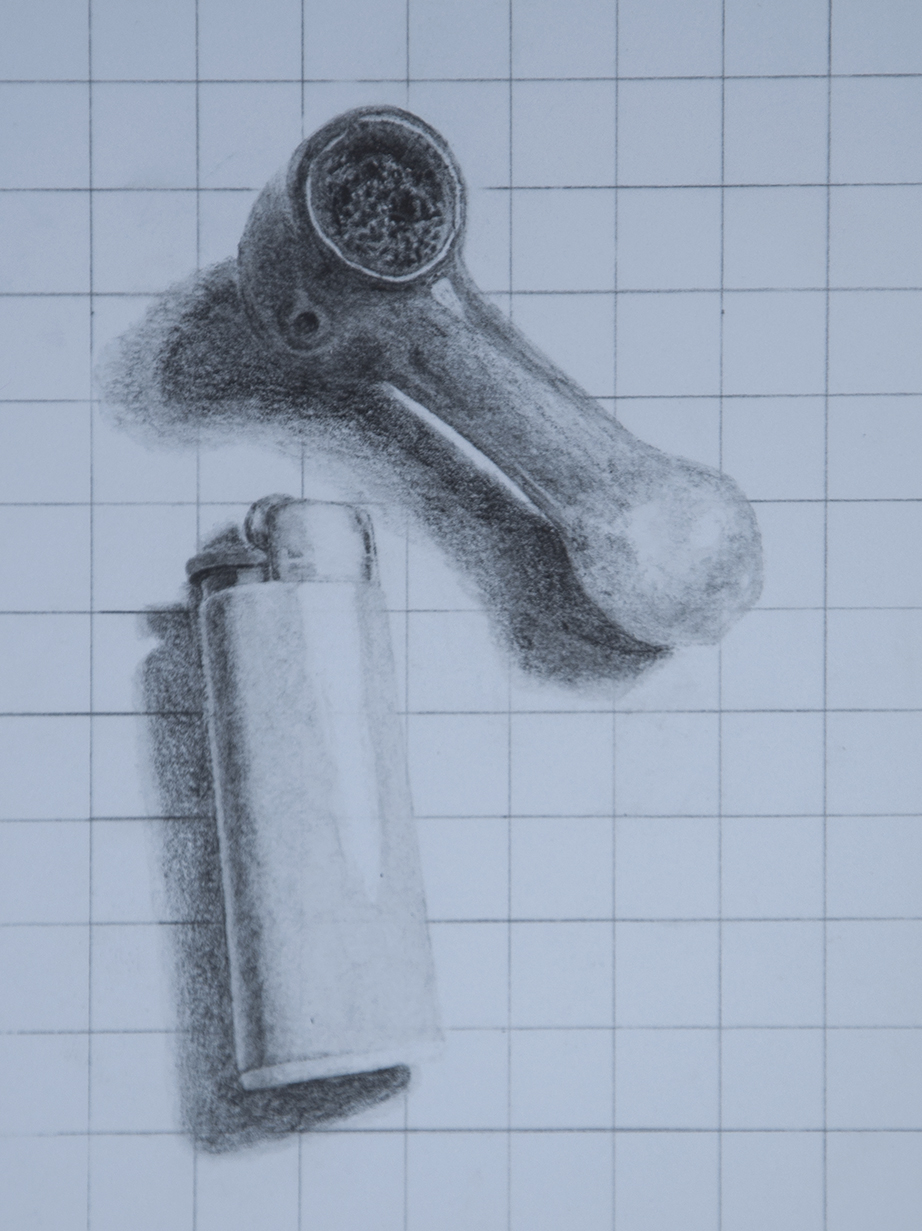

“That witch” is Witchiepoo (played by Billie Hayes on H.R. Puffinstuff). The show is about this kid on a magical adventure but it’s also about testing the limits of how blatant its creators could be on national television about getting high. Which also brings us to my drawing of the bowl and the bic lighter…

What about OCDChinatown made it the right space to present these new works? I have known Liutas for years. When he first opened OCDChinatown he and I met about doing something there but I wasn’t really sure what. Liutas has an amazing eye and mind, and his programming reflects his interests — from performances to an Eckhaus Latta pop-up shop to artist residencies. He is really open to the artists using the space in whatever way is best for them. The show went through a number of very different incarnations. I landed on a traditional gallery exhibition because that was not something the space or I had really worked with before. On the other hand, it’s also drawings and functional sculptures, both of which have a curious relationship to the story of art. They’re both time-intensive and involve a lot of craft, but neither is really the thing, you know? I feel a bit more ownership in that space.

As someone who has done product design and performance, how do more traditional mediums, such as drawing and sculpture, affect the way you view your works as consumer objects? My mom teaches art to high schoolers. She has a studio at home, and my sister and I grew up making things — everything. I make clothes — dresses, dance leotards. I make tables and chairs. I make paintings and elaborate meals and performances. I’ve watched every episode of How It’s Made and Martha Stewart Living. The Way Things Work was my “under-the-covers” book from before I could read. I like to think about commercial objects the way we think about art — the intentionally, the narrative of the creator, its relationship to history, how it will tell our story to the future. I think Martha Stewart and I would really get along. The attention to the audience that performance asks you to consider is something I tried to bring into this static show. Not in a Minimalist phenomenological way, not exactly. I just wanted more light in the room and I wanted a place for people to hang out so I made the light fixtures as functional sculptures for the space. But for every element of functionality I tried to counter it with a decision based on whatever the opposite of functionality is.