PORTRAITS BY DANIEL TRESE | PHOTOGRAPHY BY DUANE MICHALS

Duane Michals

Duane Michals doesn’t consider himself a photographer but an expressionist. A great photo, he says, should never show you reality; it should contradict it. It should challenge the way you view the world, bending and upending your assumptions. While Duane is best known for his pioneering narrative sequences — photo series that tell stories like a progression of film stills — his 50-plus-year career spans photojournalism, video art and, of course, portraiture. Duane has shot everyone from René Magritte to Andy Warhol to Meryl Streep. Dreamlike and uncanny, his images tend to offer more questions than answers. And somehow, at 87 years old, he’s still at it.

Born just south of Pittsburgh in 1932, Duane zigzagged from Texas to Colorado to Korea to New York, all before a fateful trip to Russia, where he discovered an instinct for photography. After that, Duane returned to New York and started working in the field professionally, first taking photos for magazines like Esquire and Vogue, then moving to fine-art photography and, with a MoMA show in 1970, landing the first of many prestigious exhibitions.

To hear about it firsthand, I called Duane at his Gramercy Park apartment. He was arch, dryly self-deprecating yet disarmingly insightful. Now in his ninth decade, Duane’s prolific career — which, these days, includes two simultaneous exhibitions at The Morgan Library & Museum and DC Moore Gallery in New York — has maintained its incredible speed. As he said toward the end of our wandering conversation where I laid the compliments on thick, “Yes, yes, hurry up.” There’s no time to waste, and still more to be done.

Duane Michals photographed by Daniel Trese at The Morgan Library & Museum, NYC, August 2019.

Duane Michals photographed by Daniel Trese at The Morgan Library & Museum, NYC, August 2019.

What was the first photo you ever took? I took a lovely picture of my little brother when he was about eight, standing on our porch. I published it in a book I did of portraits. It’s a very simple picture, but it’s quite lovely.

Tell me about your trip to Russia as a young man, when you began to take photography seriously. I came to New York because I liked books and magazines. I had an aesthetic itch. In high school I was the news editor of the school paper. I used to write and draw. When I came to New York I went to study at Parsons, but I dropped out because it was a waste of time.

I got a job at Modern Dance Magazine, not because I was interested in dance but because it was beautifully designed. I went from there to Time Inc., where I met a woman who discovered, in 1958, at the height of the Cold War, that you could go to Russia. So I borrowed money, I borrowed a camera, and the trip changed my life. If I had never gone to Russia, I would have never become a photographer.

What happened in Russia that made you a photographer? I discovered I was a natural at photography. It was a perfect synchronization of instinct and talent.

What should a great photo do to those who look at it? A great photograph should not tell the viewer what they already know. It should not report reality; it should contradict it. I don’t need to know what I already know.

A photo should surprise me. It should astound me. I’m not interested in regurgitating public opinions or public knowledge of reality. A great artist contradicts what you already know and makes demands on your sensibilities.

Why should art be vulnerable? Being vulnerable means that you are willing to put something on the line. You are willing to expose something that’s private. It’s easy to take pictures of someone else’s face; there’s nothing of yourself at risk there. Most photographers are comfortable taking risks with other people’s lives, but they play chicken when it comes to their own.

Sex, death, love, violence, what topics and inquiries most inspire your work? To me, the most interesting question is: What is the very nature of my experience? I started out in Catholic school believing every lie the Catholic Church told me, but now I’m an atheist. Now, at 87, I’m having my existential angst. I used to be on the outskirts of death, but now I’m coming downtown.

Until now, death was always a philosophical fascination. Now it’s becoming a fact. There’s a shift in my consciousness about how I view life. That’s been a big evolution. I have crossed the Rubicon, and I am in a much different place in terms of my reality. I’m much more interested in the very nature of being.

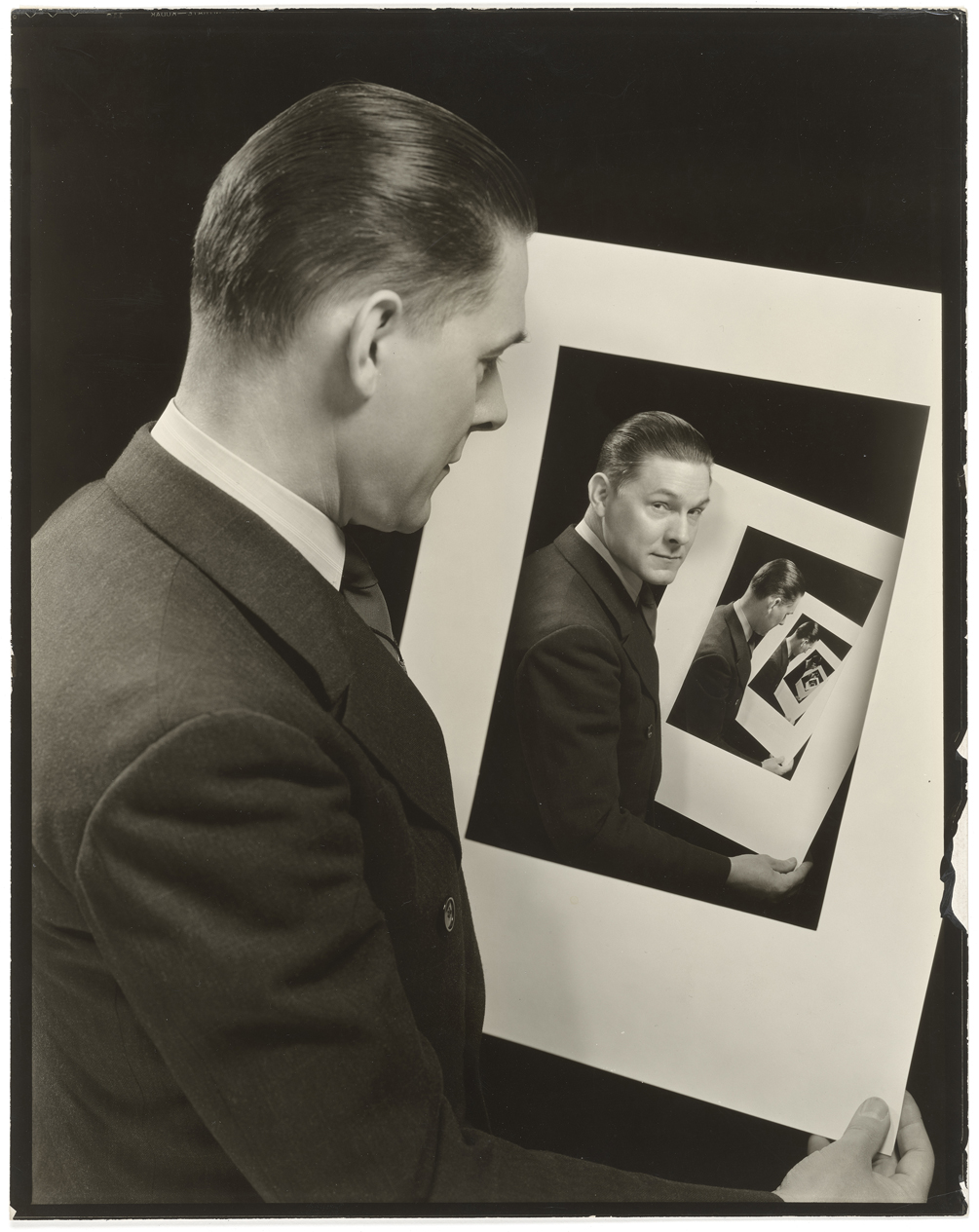

“John F. Collins (1888-1990) Multiple Self-Portrait.”

“John F. Collins (1888-1990) Multiple Self-Portrait.”

Where are you happiest? We [Duane and his assistants] did a little movie about James Joyce, and the last line said: “I was most happy when I loved the most.” I think I’m happiest when I care for someone deeply. I had a friend, we were together 57 years, and he died of Alzheimer’s. [Ed. — Duane’s partner, Fred Gorey, passed away recently] The last seven years, he stayed home and I realized what love is: Love is when the other person’s welfare is more important than your own. That’s why Donald Trump will never love anybody.

How did you two meet? We met at the gym, of course. The Sheridan Square Sports Club. In 1960, that was the only gym in town. There wasn’t a gym on every corner like there is today. I thought, Why waste all my time going to the gay bars which were like showrooms. Why don’t I just go to the factory where they manufacture them? I cut out the middleman and went right to the source.

In 1960, I was 28. It was two years since I’d gone to Russia. I was a photographer, Fred was an architect, and I loved architecture. We survived a long-term relationship because we always wanted to be together regardless of the issues we had to deal with — and everybody has to deal with issues. Nobody lives happily ever after. We deeply cared for each other.

In the end, when he didn’t recognize me very much, he turned to me one day and said, “You are my darlingest dear.” It still brings tears to my eyes. It was true. We had bumps in the road. All relationships evolve: What’s appropriate at 20 is not appropriate at 40, what’s appropriate at 40 is not appropriate at 60, and so on. So you get people stuck in timewarps, still hanging out at gay bars beating the same drum. My mother once said to me, “You either change or you fall behind.” And it’s true.

The other thing I maintain is that curiosity is the most important ingredient. If you are not curious, nothing will ever change. Change is built out of curiosity and acting on it.

Curiosity is a big part of your work, forcing the viewer to ask questions. Yes, I once said that I am uncomfortable in my comfort zone. I like evolving, questioning, being challenged.

It’s very easy for people like Mapplethorpe to photograph big dicks and people with great bodies. That’s a description of what men look like. That’s not insight. The question is not what a beautiful man looks like; the question is why I am responding to him. What is he eliciting in me?

I get very angry with gay guys who spin in the same circles. There’s no evolution. A life without question means you are dead to it. Then life becomes a very bad habit. You have to completely reinvent yourself unless you have been completely hypnotized by the culture. The gay culture, too. Fred and I were not typical gay people. Mapplethorpe would have called us Uncle Toms. We didn’t go to the gay pools. We had our lives to lead. Our lives had three, four, five, six, seven dimensions. Not just 69 dimensions, if you know what I mean.

What do you consider your biggest break? Breaks happen to people all the time. I always say I shoot first and ask questions later. When we’re born, we’re already born with certain DNA. I was born with the DNA that said I would lose my hair by the time I was 30. Then I have social DNA. I was born into a steelworking family. We were bottom feeders, Eastern European and Catholic — these were givens. I had nothing to do with these. If I had followed that trajectory, I would be married, teaching high school in Pennsylvania. But I didn’t do that. I went over the wall.

When I was 14 I read in the New York Times that you could go to Texas and work harvesting wheat. I went. It was an amazing, frightening, successful disaster. I ran into migrant workers and stuff I never knew of. Then I went to Colorado on a scholarship. So very early I began to take chances. I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing. I was a nice kid, but dumb.

When I was 28, I became a photographer. I didn’t know anything about photography. One day I was in the Village and I ran into a friend and I said, “Guess what? I’m a photographer.” I hadn’t done anything, but that’s the kind of chutzpah I had.

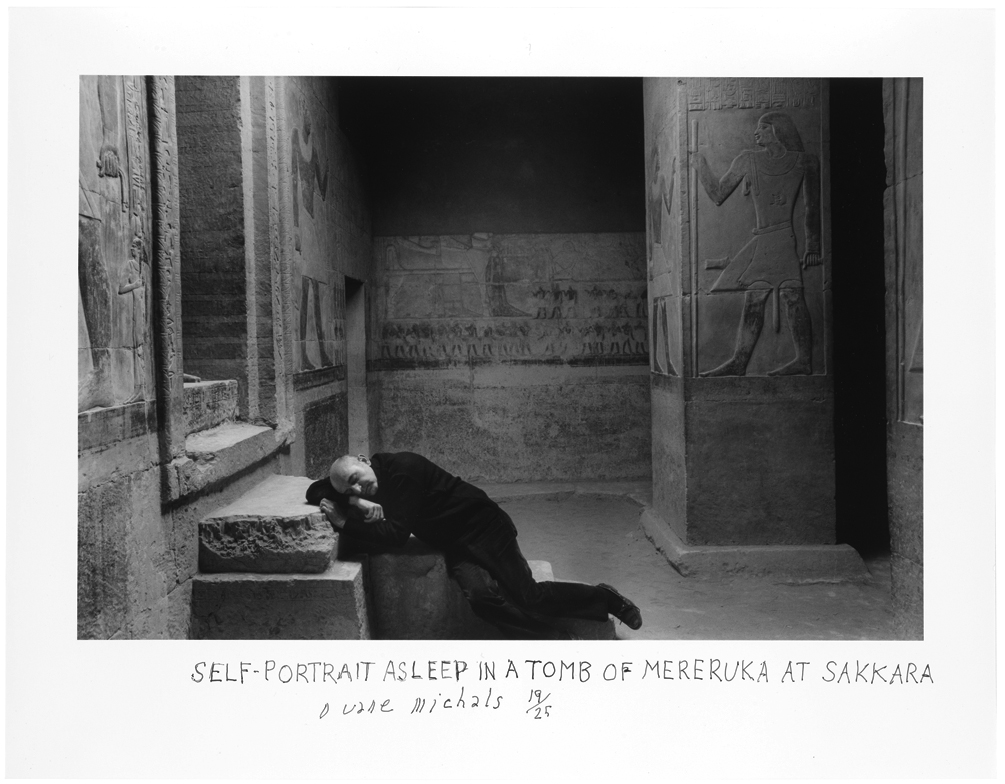

“Self-Portrait Asleep in a Tomb of Mereruka Sakkara” (1978).

“Self-Portrait Asleep in a Tomb of Mereruka Sakkara” (1978).

Do you think luck has played a role in your life? I think luck is taking advantage of opportunities. The Chinese say, “To walk around the world, you have to take a first step.” For me, going to Texas at 14 was the first step. Second step was going to Colorado. Third step was becoming an officer during the Korean War, which was the worst time of my life. I hated every minute of it. The fourth step was coming to New York. I’m still walking. Although now I do a little dance, but I’m still going.

How do you think about success? Success is finding what you love and getting someone to pay you to do it. I haven’t worked for 50 years. Success is getting as close as you can to your instincts without compromising your life away. Work is when you have to go someplace to do something you don’t want to do. Success, for me, is writing a line that I find funny. Success is making this little movie that I’m working on. It’s very, very simple. It does not mean driving a Rolls-Royce.

Who were your heroes as a young man? My first hero was Walt Whitman. I was 17. I bought his book Leaves of Grass for $5, which was a lot of money. It was the first book I ever bought, and it thrilled me. Whitman contradicted me. There I was, just figuring out who I was sexually, and he had written a poem to the effect of: “When I heard in the capitol that the president had mentioned me, I was not happy, but when I heard that my lover was coming and that he would be with me that night, I was happy.” I read that and thought, “He”? They must have meant “she.” And that one sentence was so liberating. I saw that in print, in October 1948, in the dark ages. Whitman was utterly revolutionary. His role was to contradict assumptions about who a lover could be, in 1860. It was stunning. It was brave.

Who are your heroes now? Right now, mostly artists. Politically, I like Buttigieg, Mayor Pete. I think he’s extraordinary. My example of a gay guy is him. It’s not RuPaul, it’s him. He is much more revolutionary and dangerous to the straight world than RuPaul. RuPaul can be dismissed as being amusing and nothing more. Buttigieg says, “No, no, I have a relationship with a man, I speak seven languages, and I’m running for president.” He is so revolutionary because he is so ordinary.

Let me ask you about a few people you’ve photographed. Let’s start with Tilda Swinton. I love Tilda Swinton. She’s lovely. I told her she’s the new Greta Garbo. She transcends every category as an actor. She is so intelligent, and I love the way she looks.

Meryl Streep? I just love Meryl Streep. Again, this was before she was famous. I met her in Times Square and we just had fun, jumping up and down. Then she invited me to her apartment on lower Broadway and gave me a piece of apple pie she’d made. We had coffee and her boyfriend was there. Fast-forward to about five years ago, she and I were at an awards ceremony put on by the French government, the Order of Arts and Letters. When I saw her, she said, “Duane, how are you?” I couldn’t believe it. She remembered that night as I did. She was just stunning. She is the authentic, great actress of our time, and nice. In that picture you just see the energy, the talent. She’s exploding with it.

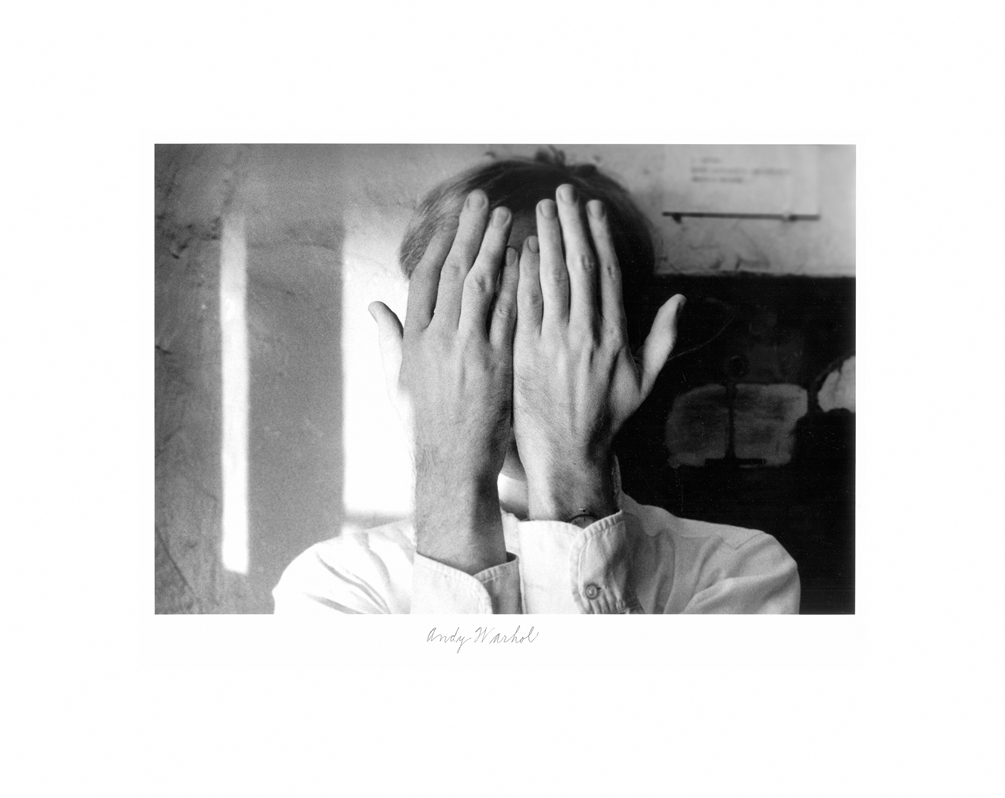

Andy Warhol? I knew Andy. He was from the same town in Pennsylvania as me. Andy was an art hustler. I knew him before he became super famous. We were having lunch and he said, “Be careful with your ideas because people will steal them.” Then he became the biggest crook in town. He stole everything.

Barbra Streisand? I love Barbra. I photographed her when she was about 18 or 19. She showed up with three shopping bags of clothes and we had fun. We got on so well. I heard her sing on a talk show, and I said, “Barbra, if I could buy stock in you, I would.” That first afternoon was just a delight. She wasn’t a funny lady; she was a funny, nutty lady.

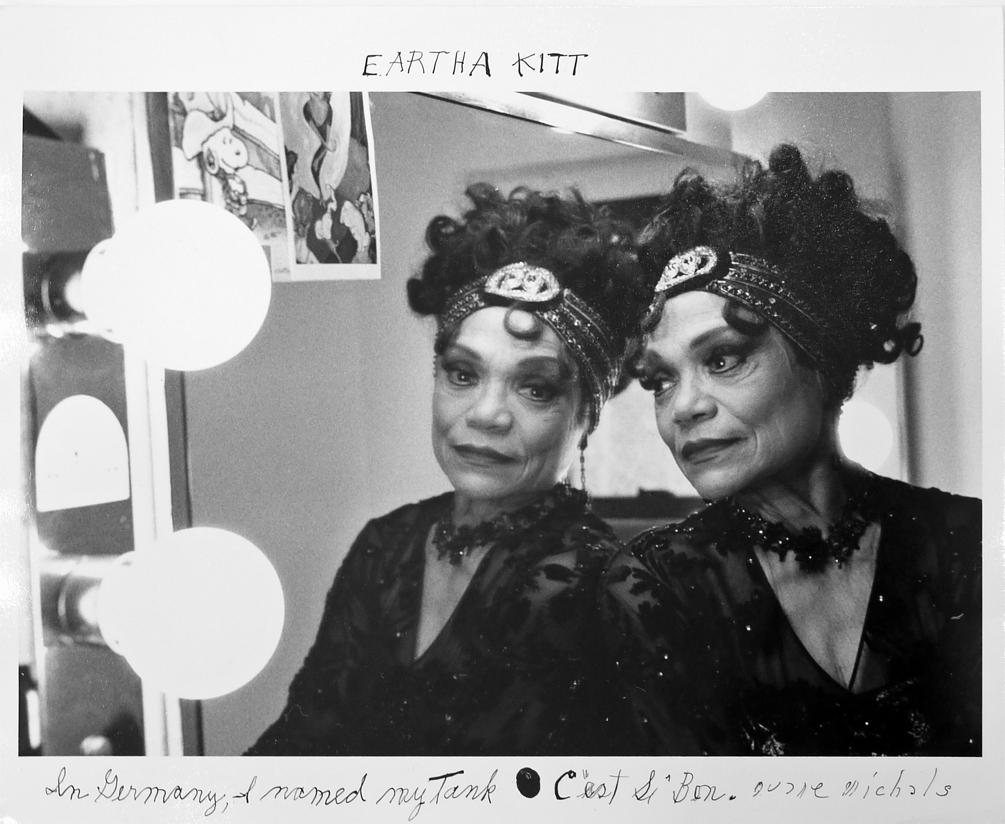

Eartha Kitt? I loved Eartha Kitt. When I met her, she was so exhausted. It was between matinees. Eartha Kitt was one of a kind. I cannot imagine what her life was like, being a black woman at that time. But she did it. She was Ms. Spectacular.

Susan Sontag? Frankly, I didn’t like her. She positioned herself as America’s intellectual. She always championed obscure Swedish movies. I read in an interview that, all those years she was talking about the genius of Swedish movies, she didn’t really like them. People like her and Andy position themselves. But I found her writings about photography nonsense. I think she was our greatest faux intellectual.

What makes a great portrait? There’s the essential part that I call “stand and stare.” Everybody does that. I don’t believe in stand and stare — it’s description. You can only make a hint about a person in a portrait, but it will only ever be an approximation. I like to ask, “What is the essential you?” The biggest scoundrels can smile; the biggest evil can be charming.

My idea of a successful portrait is when it’s one I haven’t seen before. When the portrait has atmosphere. Poetry is atmosphere. If it’s specific, then it’s basically copy in a catalog. Atmosphere is much different. Atmosphere drifts and changes shape like a cloud. Making beautiful people look beautiful is like rolling off a log. What’s the challenge? I read that Diane Arbus used to spend two days living with someone, but that’s totally nonsense. Living with someone doesn’t give you insight. You end up with the tall guy standing in the room with his mouth open, no matter what.

There’s a lot of bullshit written about portraiture. I once photographed a guy, and then I heard that he loved the picture because his nose looked small. I found out that any photo where his nose looked big, he hated it no matter how good it was. So portraits lie. It’s all about flattery.

Do you ever see yourself not working? No, I don’t, because I don’t work. Washing dishes is work. Digging ditches. I don’t work. I call myself an expressionist. To express yourself, you need to have something to express.

Do you have a motto you live by? “There are two choices in life: doing and bullshit. So do it.”

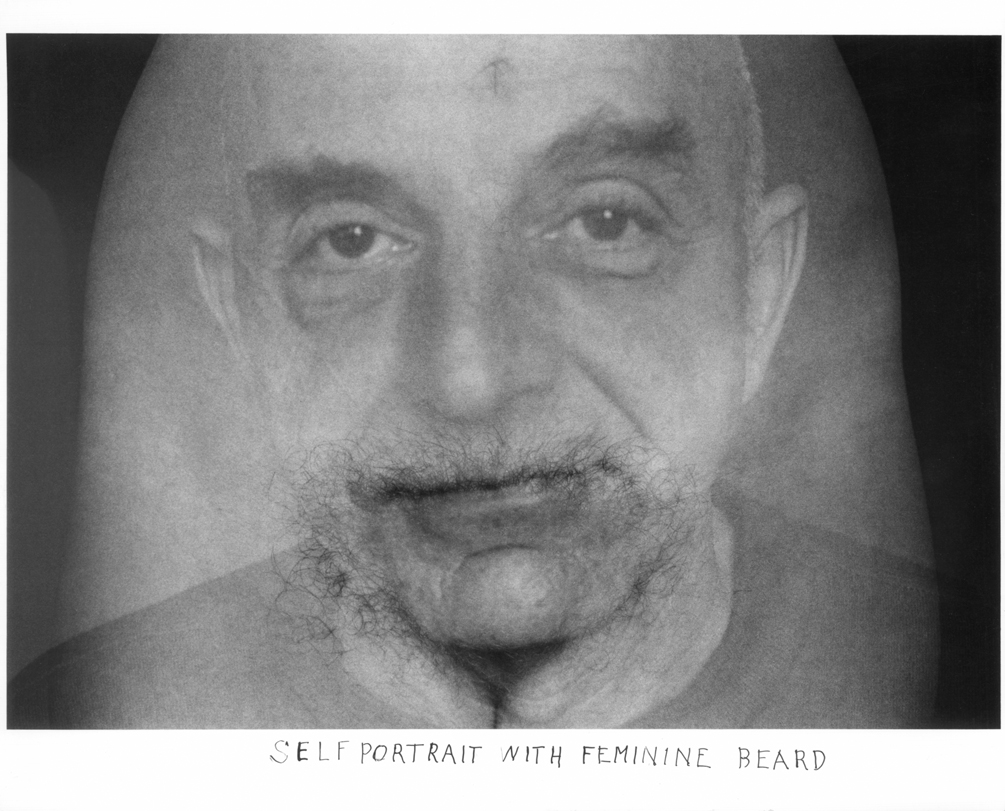

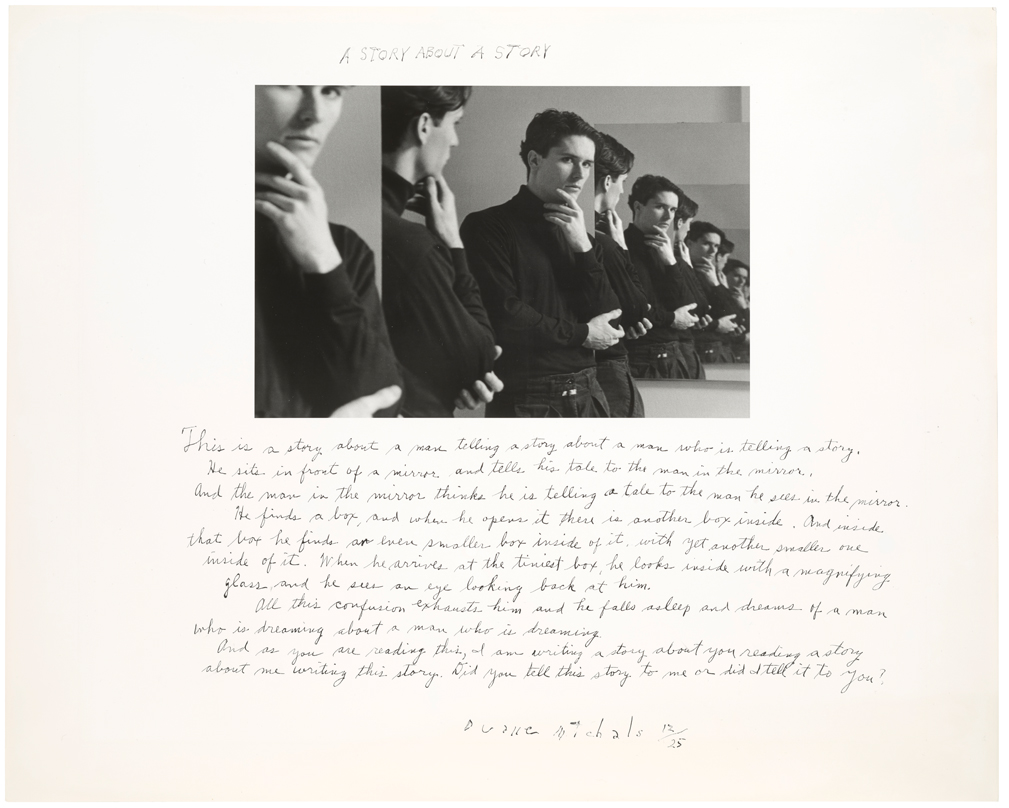

“A Story About a Story” (1989).

“A Story About a Story” (1989).

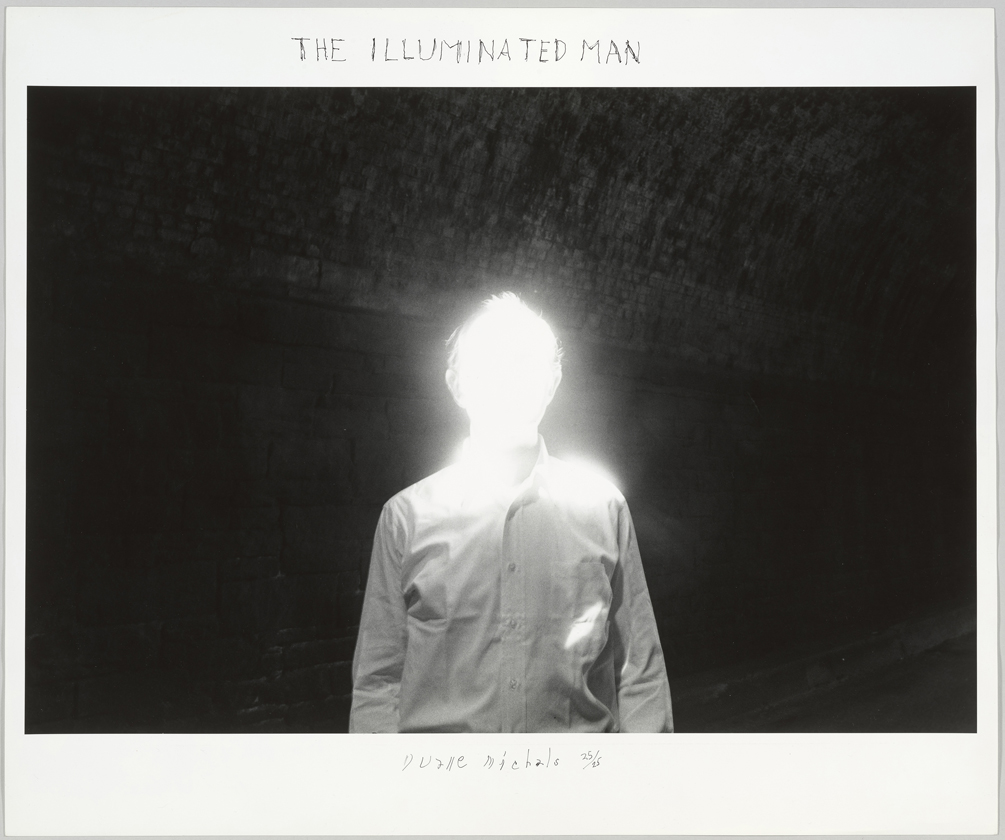

“The Illuminated Man” (1968).

“The Illuminated Man” (1968).

To see the rest of the feature get a copy of GAYLETTER Issue 11 here.

All images courtesy of the Morgan Library & Museum and DC Moore Gallery, New York.