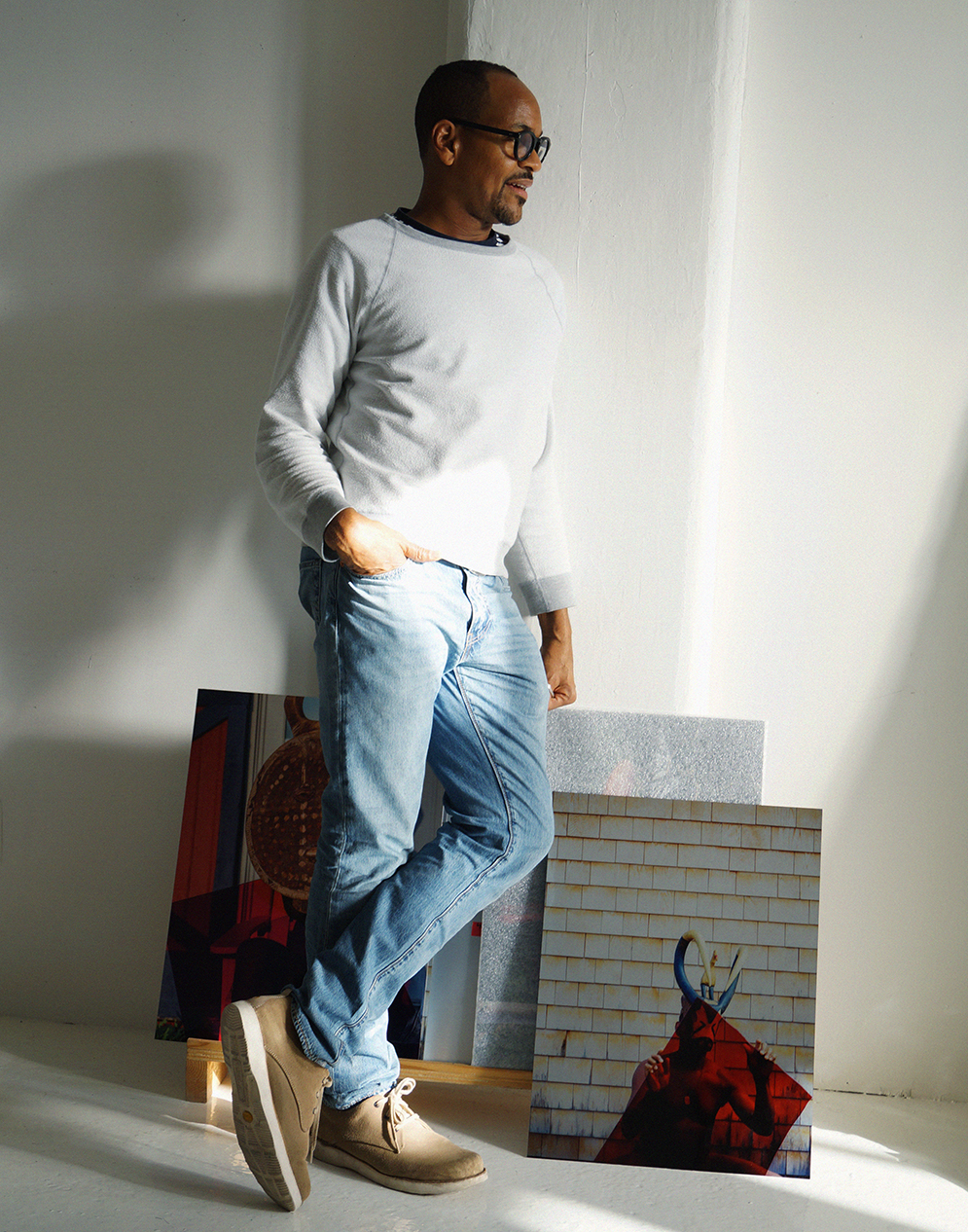

Photography by Abi Benitez. All artwork courtesy of Lyle Ashton Harris and Salon 94.

LYLE ASHTON HARRIS’ RETURN TO SELF-PORTRAITURE

The visionary talks influence, time and his remarkable career

It was a crisp Saturday in early October. In Chelsea’s gallery district, a few gallery-goers shuffled around and down sidewalks, hopping from space to space, unfazed by the wind, blind to the artist walking among them. Lyle Ashton Harris was arriving at his studio. Having been enamored by his work, and given his newest upcoming exhibition at Salon 94 Bowery, Flash of the Spirit, I was visiting him to pick his brain. Our eyes met as Lyle looked over his shoulder as he was unlocking the door to the studio building. He greeted me with a grin. “Did you recognize me?” he asked. “I just wondered…”

Upstairs, Lyle’s studio was beautifully filled with natural light. The space appeared worked-in, but generally uncluttered. As we grazed around the room, he busied himself applying light-background music (Solange, Kaytranda, Sade, Fleet Foxes, and Kate Bush) for the afternoon. Perhaps the most notable sight in his studio, both in size and palette, were two immense, unstretched canvases. The two faced each other on far opposing walls, but he quickly called my attention away from there and back toward the center of the room where a table scattered with photographs and several prints were arranged into piles. These were his latest series of portraits created over summer after a nudge from his dealer to get back to working within portraiture. Also on the table was a diorama of Salon 94 complete with tiny photos of the work now exhibited, pinned to the miniature gallery walls. He suggested we get settled, and alongside a few stacks of thick hardcover artist books and museum catalogs, we nestled into our seats, sipping sparkling water for the next two hours.

We started from the beginning. ”Well, I’m from the Bronx and I’m a professor at New York University. As a child I lived in Tanzania. I would not be who I am today without having lived in a black, African country in the mid-1970’s. Being exposed to socialism and social/cultural actualism in Africa was very important. Growing up in the Bronx, as opposed to Manhattan, was also important. I had a trajectory going from the Bronx, to Tanzania, to the Bronx, then Connecticut, then the West Coast. I remember when I met Basquiat at Area.” The memory made him laugh.“I was always aware that I wasn’t one of the wandering kids. I had a home to go to. I would ride in cabs with 10 people from Manhattan to the Bronx and then we would all fucking run off without paying. I was always with people who claimed a family for themselves, but I had a family.”

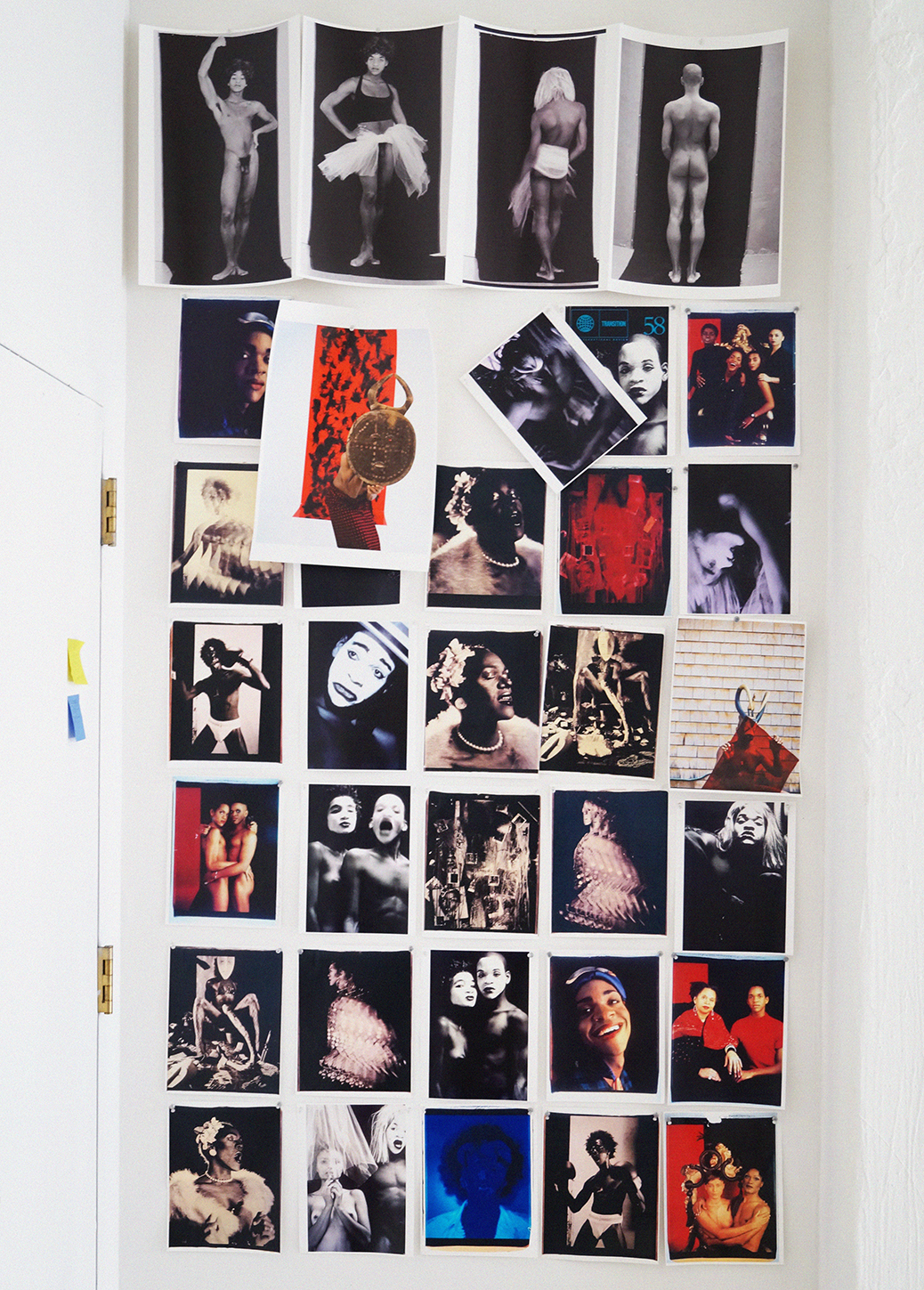

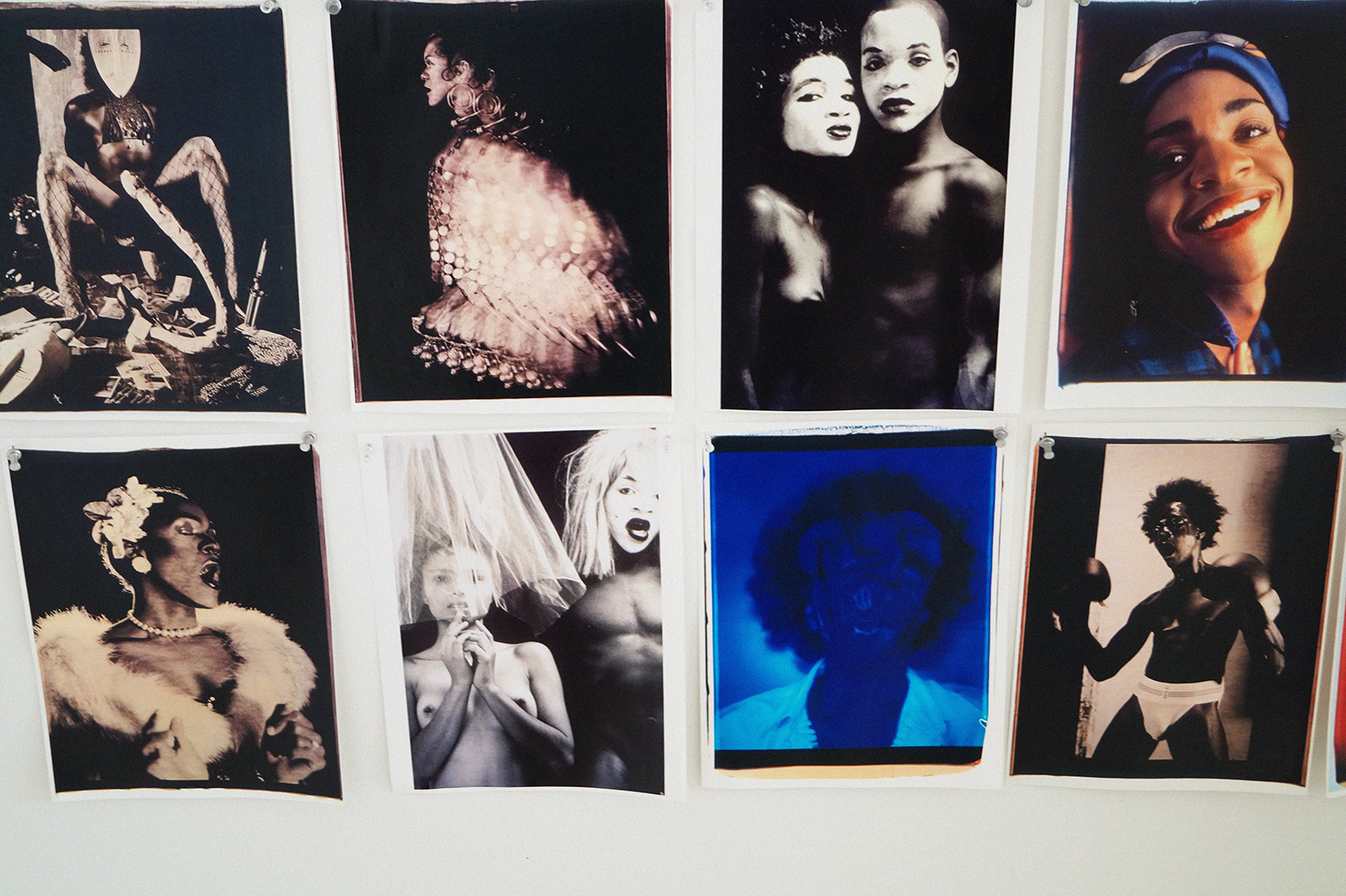

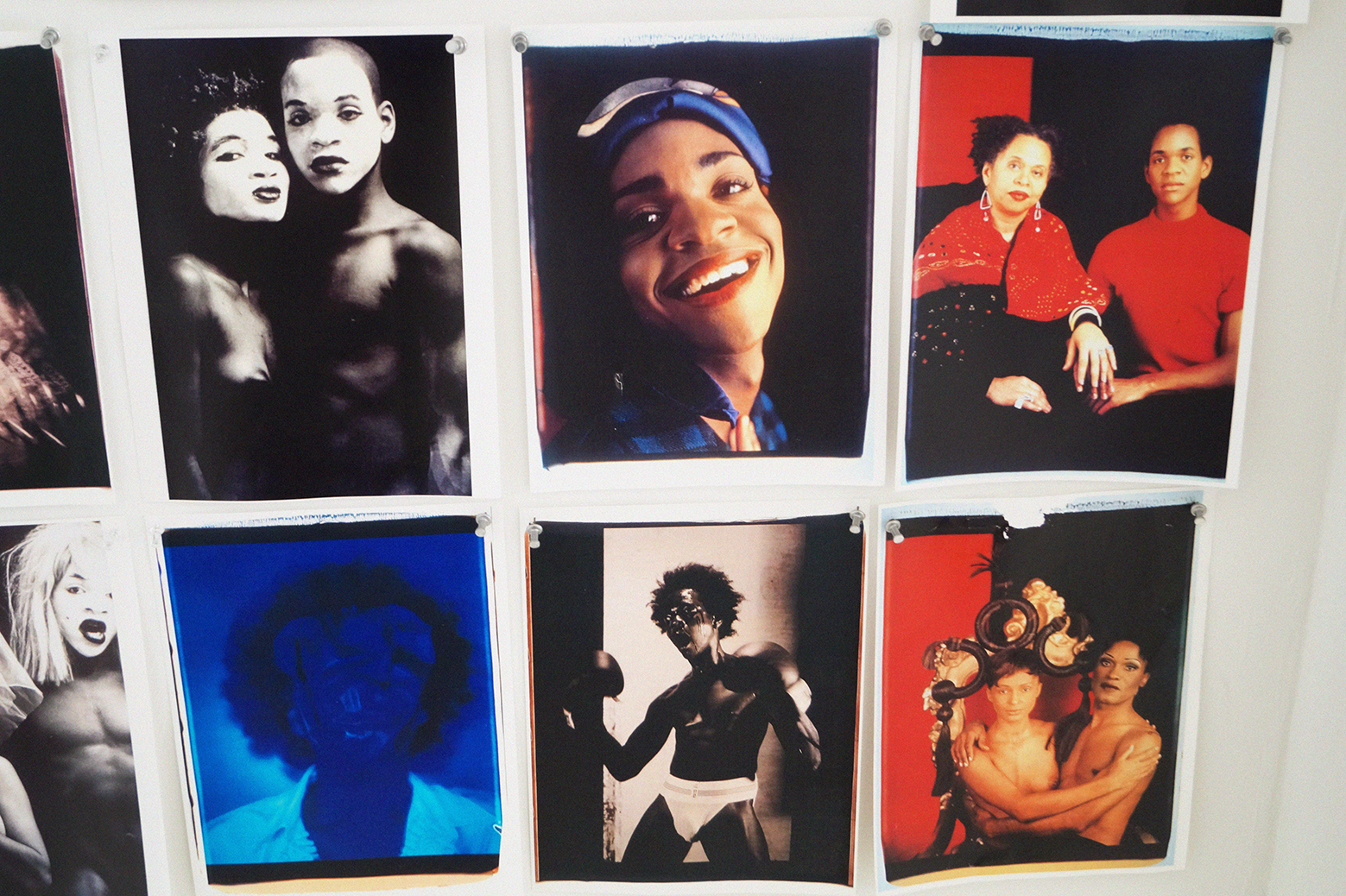

As we small-talked the woes of inter-city travel, we switched our focus to an assortment of self-portraits that had been taped to the wall adjacent to the door of the studio. Since the ‘80s, Lyle has explored and exploded all kinds of identities: race and ethnicity, gender and sexuality, social class and the enigma of fame. His portraits conjure a simple elegance as the artist shape-shifts into whatever guise that proposition the most interesting questions.

In a moody black and white series titled Americas (1987-88), closely followed by Constructs (1989), the artist posed solo and with friends, naked or draped in the American flag, frowning and writhing in whiteface while wearing choppy blond wigs, or sporting a long piece of tulle tied around the waist like a dancer’s tutu. A selection from the constructions was included in 1994’s Black Male exhibition at the Whitney Museum. As we discuss the photographs, Lyle explained his whiteface.“If you think about vaudeville culture in the nineteenth century, you have white men portraying not only females, because females could not be on the stage, but also black people, as they could not be on the stage either. I’m interested in how these elements of transvestism sparked within the American psyche through vaudeville theatre.” He noted that the photographs were a type of drag performance but with a consciousness toward the history of performing race and gender.

Also on his studio walls were photos from The Good Life, Lyle’s first New York exhibition presented by Jack Tilton in 1994 in which, accompanied by other artists, friends, and family, he expanded his subversive photographic themes in rich jewel tones, creating quick narratives in each frame: A black policeman wearing lipstick (titled Saint Michael Stewart, in reference to the 1983 incident of police brutality in which an African-American man died while being held in custody for spray-painting graffiti in a New York subway station); a family portrait with gender-bending parents holding their sleeping child; a naked kiss between two men as one presses a gun into the other’s chest (actually a collaboration with Lyle’s brother, the filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris, who also appears in the photo). These images often raise more questions than they answer. “It is an interrogation,” Lyle asserted, “but it is also about seduction and play. I think my relationship to gay culture has been critical to my work over the years, but this relationship is made more complex when you consider historical perspectives, by mixing black literature, art criticism, and American pop culture. I would say that the work has always been multi-pronged for a lack of a better term.”

As we continued to inspect the wall in Lyle’s studio, we bridged onto the subject of his fascination with celebrity. Among the images on the wall were Lyle’s darkly romantic pictures of the artist dressed as Billie Holiday from the series Billie, Boxers, Better Days (2002). It would not be the only time Lyle inhabited the role of obsessor. Another work from the same era Performing MJ (2004/06), is a tribute to Michael Jackson, performed at Yale University and the Studio Museum in Harlem. It was a feast for the senses as the artist embodied a frenzied version of the musical legend – arriving in sunglasses and a wheelchair but soon dancing half naked in heels and banging on bongo drums as he scattered pages of ephemera across the floor. The Watering Hole (1996), Lyle’s work about serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer includes a pair of mixed-media works that are part personal scrapbook and part detective’s wall of investigation. He uses a range of photographic media, collage, installation and performance to present both a personal image and an indexical archive, a self-aware way of processing history.

Perhaps it is that self-awareness that has led to his work’s increasing depth. Many times during our visit to his studio, Lyle became self-critical, asking, “How do you find me?” and, “Am I speaking too abstractly?”, or qualifying with “If that makes any sense, I hope that’s clear.” He apologized with charm throughout the duration of our visit. “I’ll say very frankly that I could talk a mile around something opposed to hitting it. There’s a part of me that can get so caught up in the academic language, you know?” These micro-reflections, though arguably self-deprecating, always seemed to come from a genuine desire to communicate his truth. However, Lyle explains that he wasn’t always so self-aware. “The photographs that comprise what I call the Ektachrome Archives (1986-00) were snapshots when they were done and I never imagined showing them as art.” Those 35mm ‘snapshots’, emblematic of the second wave of AIDS activism and the multicultural optimism of the ‘90s, comprise an extensive personal album of Lyle’s family and friends, featuring a mix of art world characters – including Nan Goldin, Catherine Opie, Glenn Ligon, Renée Cox, Klaus Biesenbach, bell hooks, and Isaac Julian. Many of the images have now been shown at David Castillo Gallery and Sommer Contemporary Art, and they also formed the content of a site-specific multimedia projection installation shown at the 2017 Whitney Biennial.

“I think why people are really drawn to [Ektachrome Archive] is the purity in the way the eye sees, unlike when I was making The Watering Hole, when I was setting out to make art.” Most of the photos were captured before Lyle entered graduate school at CalArts. Before, Lyle claims, he was polluted. “Before I turned that turn, before I became a quote unquote ‘artist.’” The archive, Lyle believes, came from his natural impulse to document. He attributes this natural impulse to document to the influence of his grandfather, who was an amateur photographer, capturing family and friends throughout the years. “It was my way of negotiating the world,” Lyle said. “Being young, being queer and being an ingénue, being out at night in spaces having fun with people who have gone on to become well known. When I was in graduate school I was cute and I was smart and somehow, I wanted to be part of it more and the camera was a way into that.”

At this point, our conversation had reached a pause, and we collectively began to admire the warm October evening beginning to mill in from the windows, bouncing off the white walls. I raised a theory, cause why not? Having deeply familiarized myself with Lyle’s work throughout the years, I had begun to split his work into two different categories. An idea I feared he’d hate. Some of his work is made from the perspective of the archivist, who is constantly distilling and blowing up, reconstructing and deconstructing experience. He replied before I finished, showing interest. I continued, citing his role as an image maker, one who examines culture and then organizes and creates a new image that might make the members of said culture think. “That’s smartly distilled,” he said, chuckling. He noted that my two categories often overlap within the works too. But would the image maker return in the upcoming show? “I would say definitely, yeah.” he answered. “There is an archivist part of me that is about the historical and creating that space as a form of service to myself and others. Then there’s also the part of myself who is about luxuriating. I’ve noticed with a lot of my students now who are young and queer, that there is a return to the romantic, and I’m finding that they are troubled by the lack of intimacy that exists in social media settings. So I am interested in working against that by seeking out genuine connection and interaction, complex and rich and deep because I find that there is a way in which we, a lot of us, have turned over our sexualities.”

After some playful discussions about our comedic errors on various sex apps, we returned to the subject of our visit, the upcoming show at Salon 94 Bowery, which opened November 9th and continues through the third week of December.

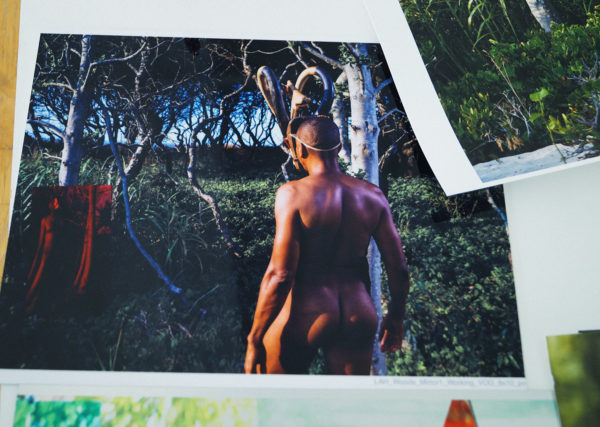

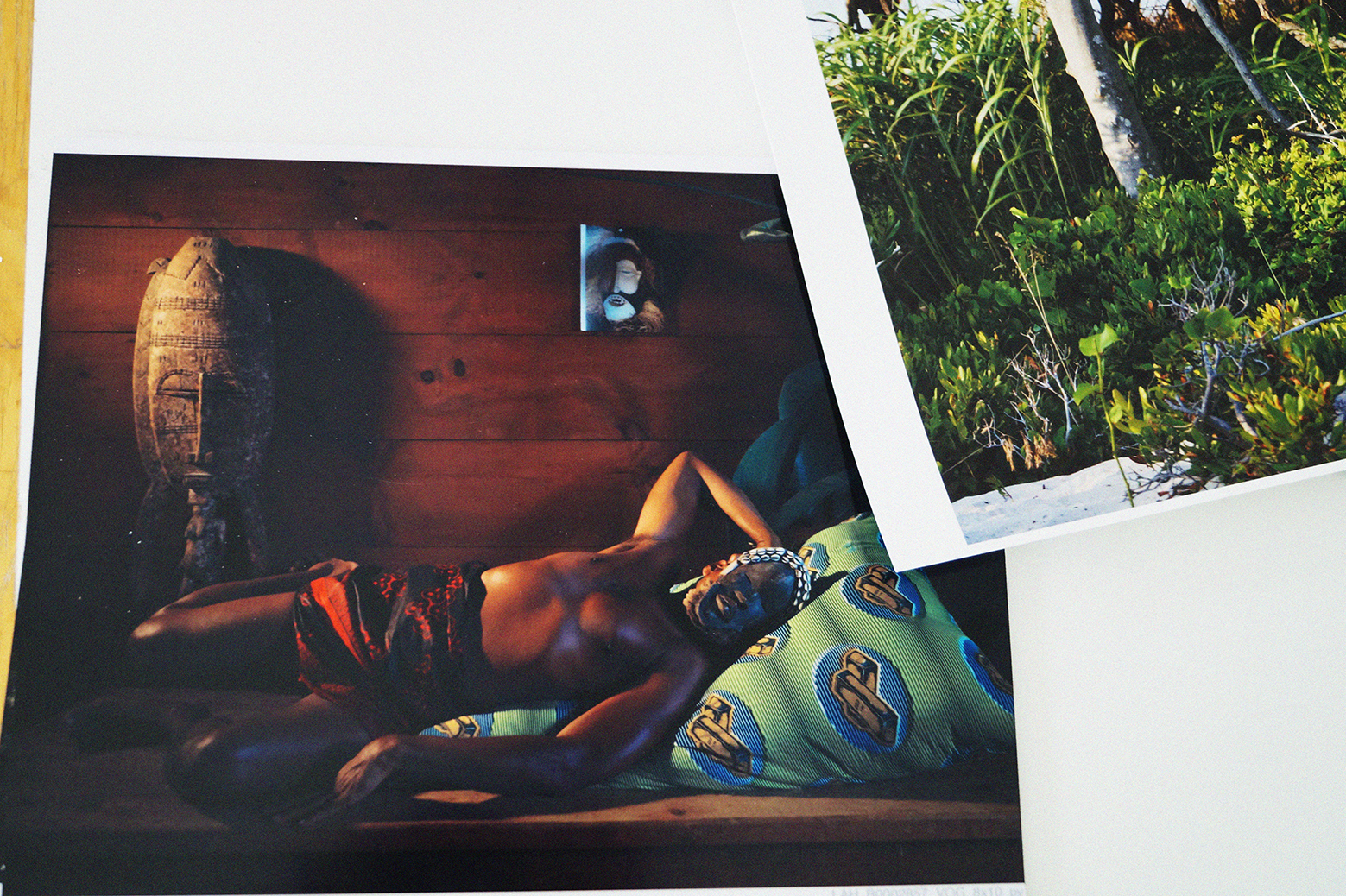

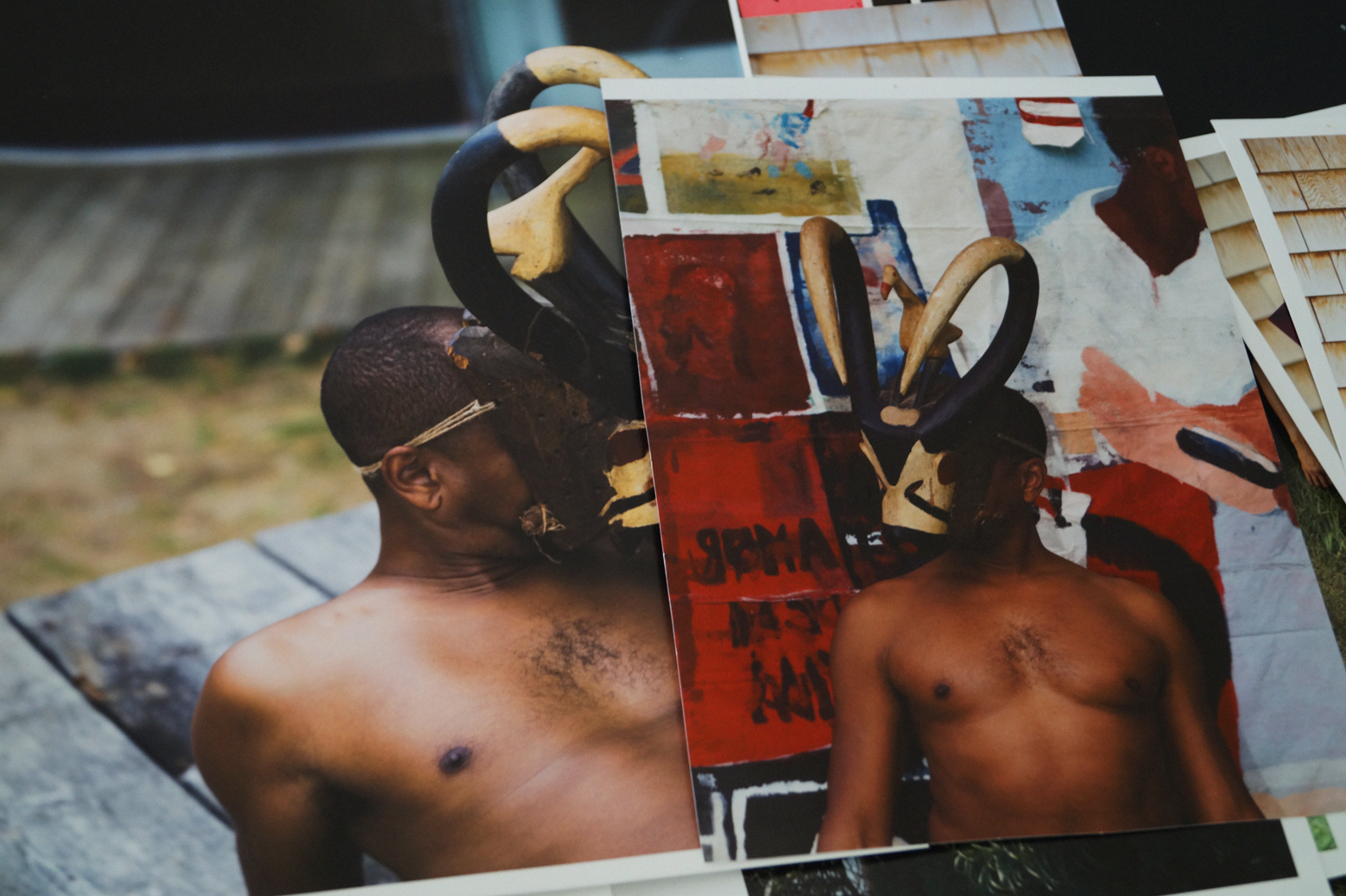

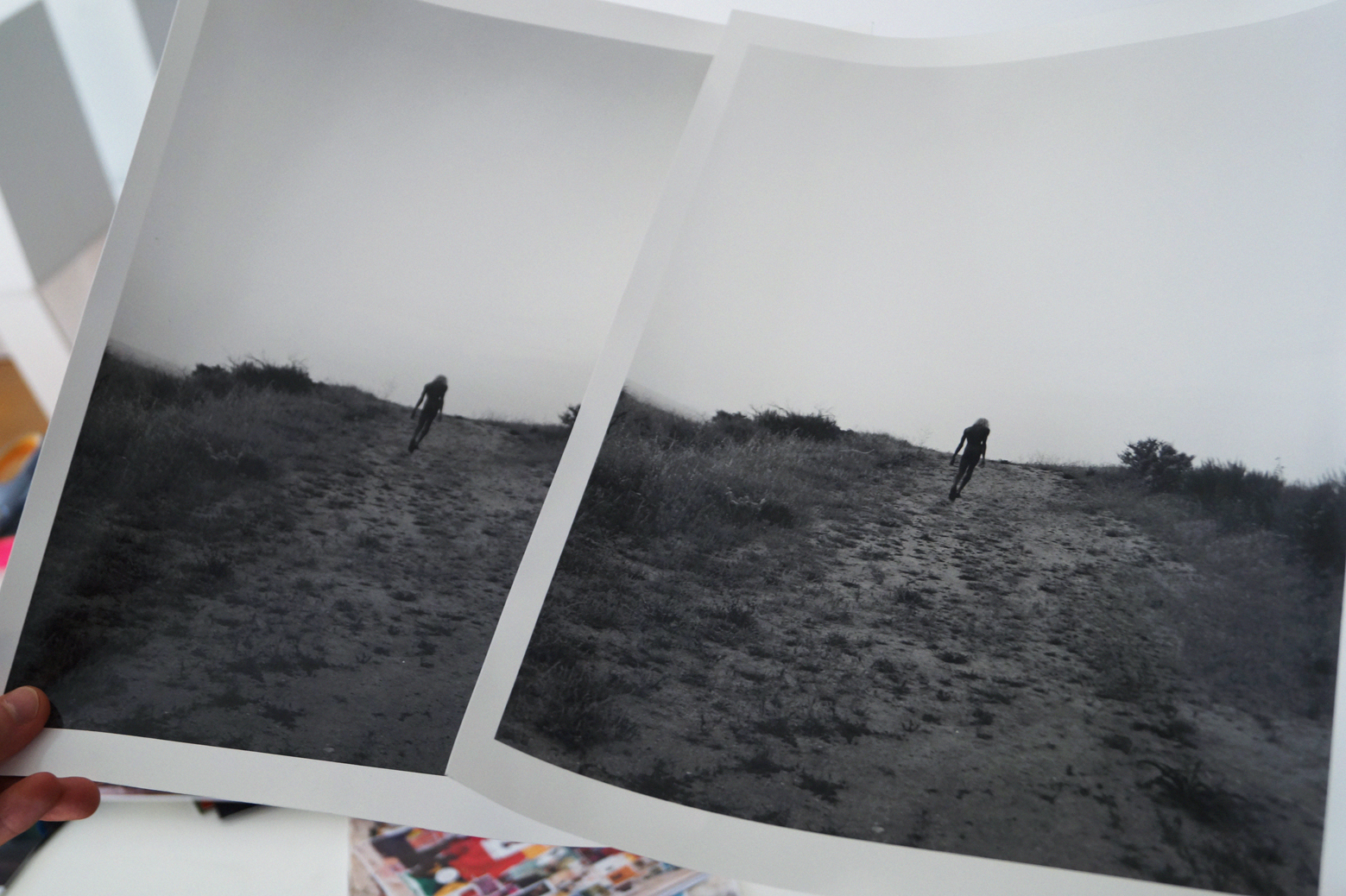

In the new work, Lyle wears masks, several borrowed from his family’s collection of African masks belonging to his uncle, Harold Epps, who traveled throughout West Africa in the ‘60s. He’s seen gyrating in natural spaces, bearing large mirrors and pieces of colored fiberglass. Although his body has visibly changed since his early works, his physique remains strong, fortified with a sensual wisdom. “What I like about this new stuff,” he muses, “I think there is the element of the erotic that has returned to the work, 20 years later. There is an element of abandonment as opposed to it being all about a critique. I saw the masks when I lived with my father in South Africa and when I also lived as a child in Tanzania during the early budding of my sexuality. I don’t necessarily see using them as appropriation as opposed to an engagement with a complex cultural history.”

“It’s been intense because my dealer asked me to do self-portraits, and it wasn’t part of the trajectory. I was off considering the [the large canvases near the windows]. I also lived in Ghana for seven years from 2005 to 2012, and I was engaged to someone there. That didn’t work out though because he couldn’t come here, so I got back here in 2013. At that point I discovered 3000 slides I had deposited after I won the Prix de Rome in 2000, snapshots if you will, from my mother’s house in the Bronx where I grew up. That was the genesis for what became the Ektachrome Archive”

So now, Lyle has returned to self-portraiture. “I spent a lot of time this summer in Fire Island and Provincetown. Both gay destinations, and after several years visiting both places, I recognize that they have different sensibilities. I like the fact that Fire Island is a community setting. You have to cook, you know, there are no restaurants to speak of. These are curious places to interrogate, Provincetown and Fire Island, where queerness is prized but whiteness is still predominant. In a way, I don’t want to go out there, where I might hang out with friends, and in a photograph of ten people, one is a person of color.”

As we skirted on the subject of racial biases in art world institutions, Lyle announced, Lyle said he feels younger than he did ten years ago. As a professor, he feels connected to a new community of young people that are shaping the future of arts business and catalog. “There is still a certain realness,” he said. “In the last several years, I became less enamored with institutions, and much more connected to the people directly around me. My students aren’t interested in cultural acceptance, but cultural authority. I’m very aligned with an institutional shift. Institutions are realizing they need to adjust to be viable.”

“I’m more concerned with alienation from myself than from institutions. For me it’s about healing. I want to stand my ground in my sacred space, and that is different from ten years ago. My old work now seems topical, but at the time it was incendiary. That has been a recurring issue for me: making work ahead of its time and having to wait for culture to catch up as history is being expanded. I’m inspired by this next generation of people who have unfinished business to get done.”

Our conversation came to close with the obligatory question, “Do you have any advice for young queer artists?” The question made him smile. “I would say that I’m taking advice from them,” he said, warmly. “Even the energy being put forth in [GAYLETTER]. I think it’s important to research. There’s a myth that the internet provides everything, but I am often struck by the younger kids’ hunger for cultural history. You know, after the March for Our Lives in Washington, seeing those kids after that shooting. These kids are on it.” He offered a quick hug as we left the studio. It was a hopeful ending, maybe exactly what was needed.

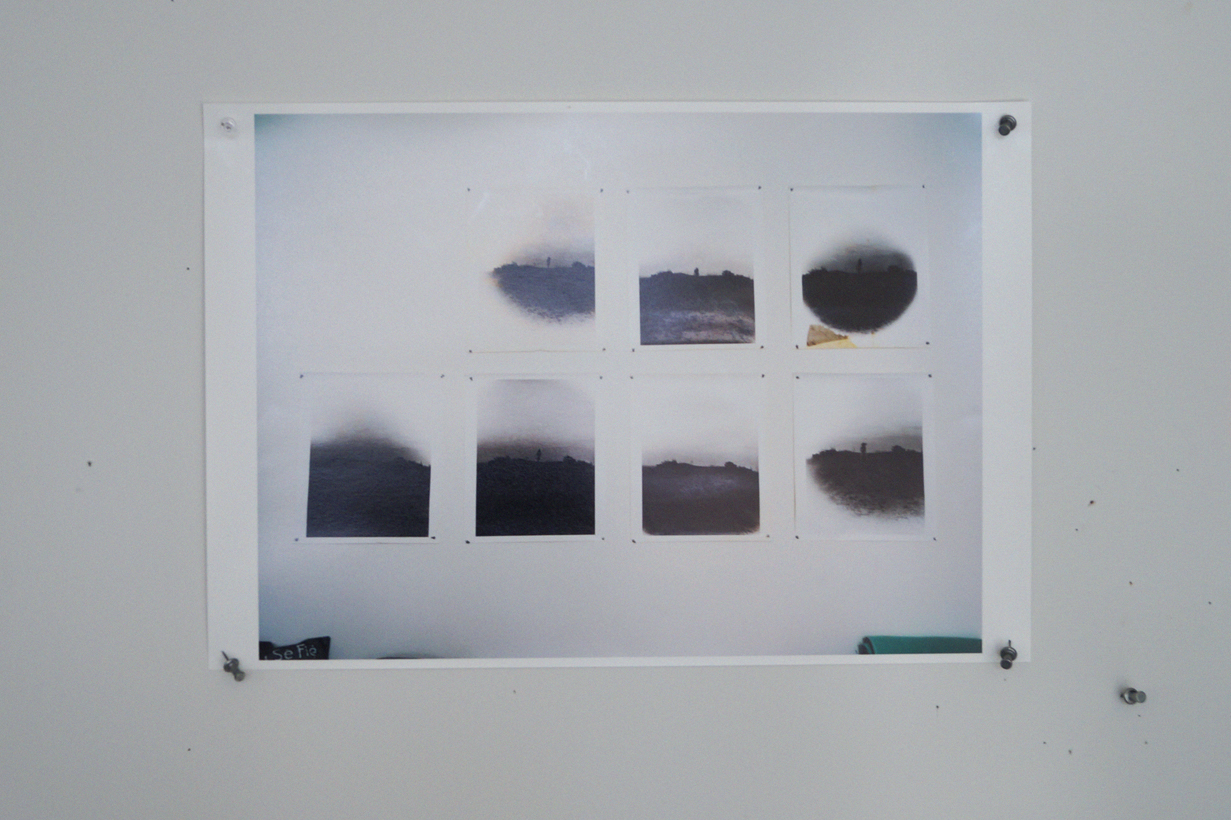

Lyle Ashton Harris, Flash of the Spirit, 2018.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Flash of the Spirit, 2018.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Zamble at Land’s End #2, 2018.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Zamble at Land’s End #2, 2018.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Nocturnal Guardian #1, 2018.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Nocturnal Guardian #1, 2018.

All images courtesy of Lyle Ashton Harris and Salon 94.

Lyle Ashton Harris is open at Salon 94 Bowery (243 Bowery, NY, NY.) on November 9 and runs through December 21, 2018.