PHOTOGRAPHY BY LEONARD FINK

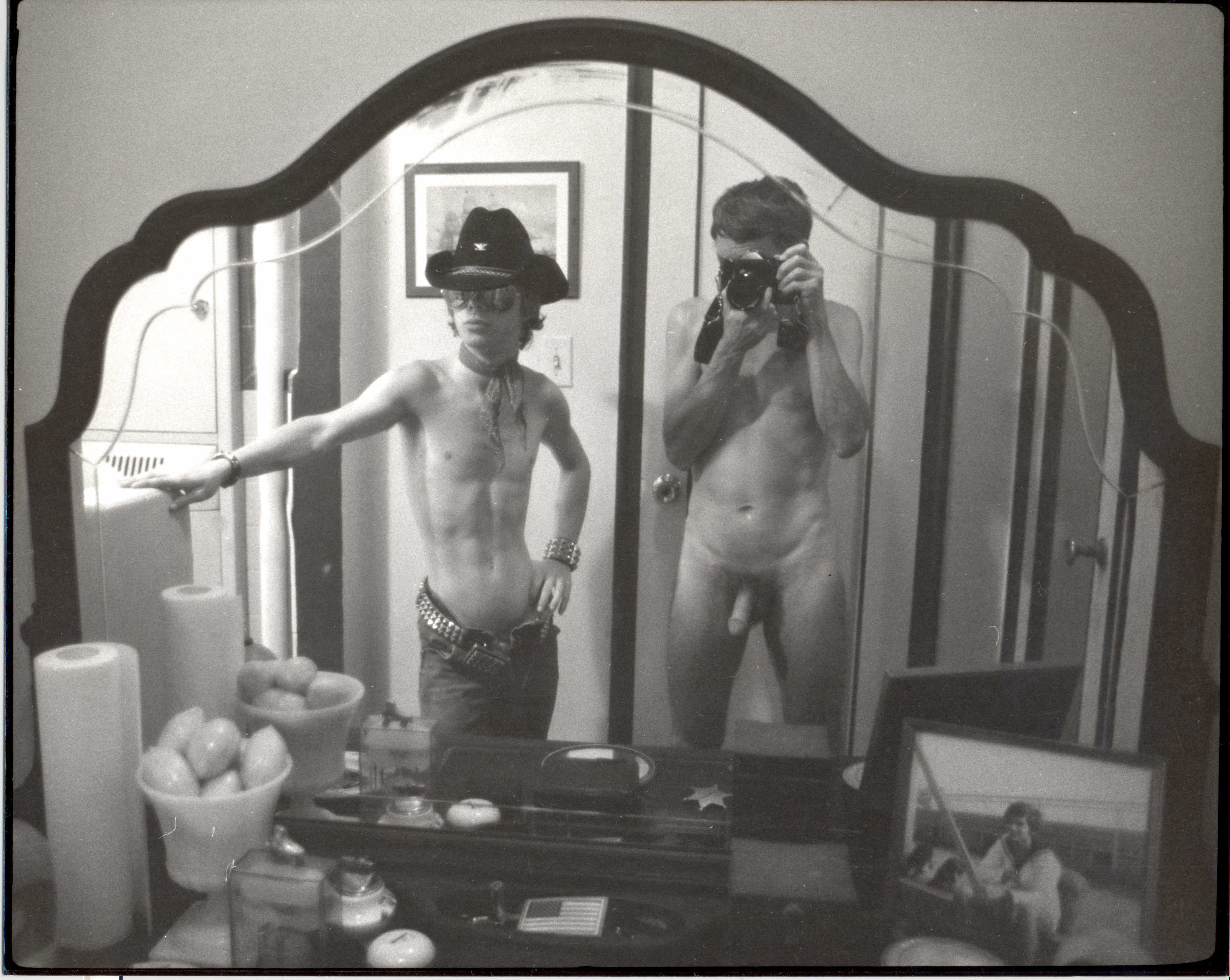

OUT FOR THE CAMERA: The Self-Portraits of Leonard Fink

Scenes of the sexual, the social and the historic at this intimate exhibit.

As a newcomer to New York City I made my first trip to the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in Soho a couple of weeks ago. I arrived dazed and sticky, not yet used to the stifling midsummer heat or the Canal St. crowds. The museum, on the comparatively quiet corner of Wooster and Grand, felt like a place of refuge. I felt weary and immediately grateful as I walked in. Inside the museum is both stark and warm. With its soft lights and wood floors the gallery space cultivates a comfortable intimacy in its visitors. The same intimacy naturally carries through to the relationship between the visitors and the exhibitions, between the visitor and the art. As I explored OUT FOR THE CAMERA: The Self-Portraits of Leonard Fink, one of the two exhibits currently on view at the museum, the exchange between the space, the visitor and the artwork itself made itself clear.

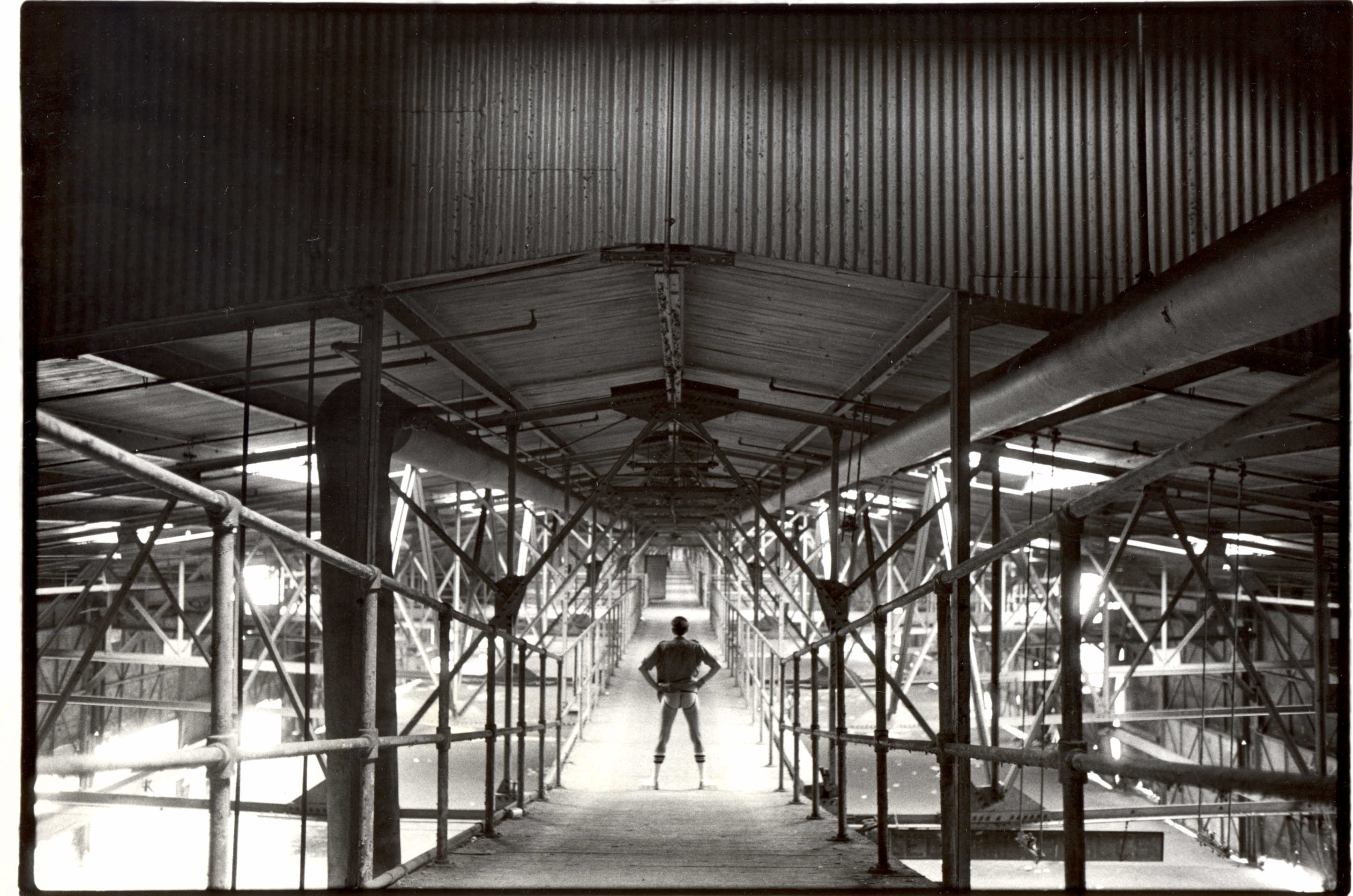

During the seventies and early eighties Leonard Fink, a gay man, photographed New York City, paying particular attention the social and sexual lives of his fellow LGBTQ people. He captured the bar scene of the West Village and the annual Pride marches and the men cruising for sex on abandoned piers, documenting LGBTQ culture from the interior. During his lifetime Fink’s work was never recognized and today it remains mostly in obscurity despite its contemporary relevance. He, like other LGBTQ photographers such as Alvin Baltrop, Peter Hujar or Diana Davies have long been role models for aspiring photographers. Only now with the resurgence of LGBTQ activism and the demand for institutional inclusivity are these remarkable artists coming into the foreground of American LGBTQ art. I too was unfamiliar with his work, though quickly I recognized something familiar within his photographs. There seemed to be an emotional constant between his images and those of my own world, a kind of lonely undercurrent spanning the two otherwise disparate landscapes.

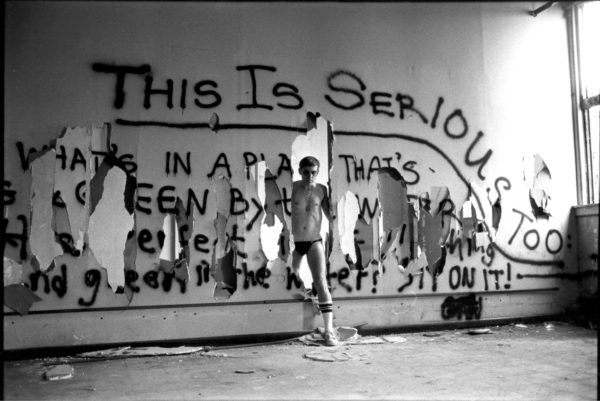

In the gallery Fink’s silver gelatin prints show bare skin and nervous, anticipatory glances; large-scale graffitied cocks and men having sex halfway in the shadows. There are men in leather jackets sitting stiffly atop the pool table in a hazy bar, others sprawled naked over a beach towel and swathed in sunlight. There are the familiar faces of Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, two pivotal figures of LGBTQ history, marching together in an early Pride demonstration. In the repeated scenes on the piers there is again and again images of decay and industrial squalor repurposed into makeshift private spaces. Above all I recognized a familiarly constant wariness and the loneliness which lurks beneath it.

Accompanying Fink’s photographs is a selection of works which relate to his either by theme or by subject. There are cartoonish figures that echo the concrete wall murals of the waterfront cruising grounds and colorful photographs that capture the piers from an observational distance. Also included in this selection is a portrait of the artist David Wojnarowicz by Hujar titled, David Wojnarowicz, Manhattan-night (II). Shot in 1985 the black and white image shows Wojnarowicz from the chest up in front of an industrial cement background. He stares directly into Hujar’s camera, his face worn and half-covered by the shadow. In the candor of the image David looks immediately and startlingly earnest. An exhibit of David’s own work is now open at the Whitney, titled History Keeps Me Awake at Night, which also features Hujar’s portraits.

When I got to this point in the exhibit I stood in front of Manhattan-night (II) for a long time, arrested by the work’s emotional honesty. I had been thinking of both Hujar and Wojnarowicz throughout the exhibit for the thematic and temporal overlap between Fink’s work and their own. Like Fink, Peter Hujar photographed the faces and the culture of downtown Manhattan during the seventies and eighties, though he died of AIDS-related pneumonia in 1987. Wojnarowicz, Hujar’s lover and the most widely known of the three artists, worked in the East Village during this time as a painter, photographer, filmmaker and writer. After Hujar’s death and his own simultaneous HIV diagnosis Wojnarowicz’s work became an intensely political and personal real-time document of the AIDS crisis. In 1992, both Wojnarowicz and Fink died of AIDS-related illnesses.

I stared at David’s portrait for a while and I came back to it again before leaving the museum. In the midst of Fink’s documentarian images Manhattan-night (II) felt cutting and intimate. Where Fink’s prints perform like artifacts, Manhattan-night (II) finds power in immediacy and a lack of distance between viewer and subject. At its most pragmatic the portrait provides an emotional link from past to present, visceral and sharp like a parable or a passing glance in a sidewalk mirror.

When I left the museum that day I left with a sense of belonging, as though a conversation or an exchange of some sort had taken place. In this way the visit underscored just how important it is to have museum spaces like the Leslie Lohman carved out specifically for queer art. The influence of these LGBTQ-centric spaces is made more apparent now than ever as other museums follow suit, presenting exhibitions centered around queer artists and subjects.

OUT FOR THE CAMERA: The Self-Portraits of Leonard Fink is on view through August 5th at 26 Wooster St. New York, NY. 10013 (Between Grand & Canal Streets).