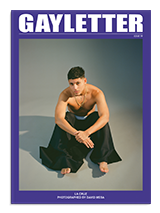

Stills from the film

They

Anahita Ghazvinizeh’s film handles the gender binary with deft lightness.

They, by Iranian-born director Anahita Ghazvinizadeh, begins with a voiceover. Fourteen year old J, the film’s protagonist, is talking with their doctor. We learn that J (Rhys Fehrenbacher), who uses the gender neutral pronouns they/them/theirs, is taking hormone blockers to “hit a pause button,” preventing the onset of a puberty J just doesn’t want. Their doctor tells them that the blockers are negatively affecting their bone density, that it’s time now to make a decision. It is here that J’s doctor mentions exploration, but it’s exploration for some sort of end goal. Ultimately, they are talking transition. The doctor asks J, “Are you ready?” The question hangs like a moment of suspended animation, and carries on through the entirety of Ghazvinizadeh’s film.

They takes place over one weekend during which J’s sister Lauren (Nicole Coffineau) and her Iranian boyfriend Araz (Koohyar Hosseini) come to stay at the house with J while their parents are away. Lauren is an artist, and she tells J about her various artist residencies and, more potently, the frivolity her and J’s parents assume of her profession. There is also Lauren and Araz’s impending marriage, complicated by the decision Araz has to make: whether to stay in the U.S. with Lauren or return to Iran to be with his family. Over the weekend J’s own internal struggle is a constant hum beneath these intertwined plots, bubbling up from time to time to take priority. In this we see that the film is not merely J’s coming-of-age story but a complex web of questions about identity, with J’s gender identity panning out alongside Araz’s identity as an Iranian in America, and Lauren’s forging of an identity as an artist.

Ghazvinizadeh, whose film education comes from both the Tehran University of Art and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, handles these stories with a deft lightness. She counterbalances nuanced and substantial issues with blurred, obfuscated visuals and airtight dialogue. Frequently we hear a voice without a face, or we watch a conversation unfold from the vantage point of the unobtrusive outsider. These technical choices put us in the same kind of stasis that J is relegated to by the force of their impending decision. A quiet, uncomfortable sense of anxiety permeates the film, which does eventually gains force in tandem with the tender, familial bond between J and Lauren. Even Araz demonstrates a similar kind of care for J. He nervously probes Lauren about the correct use of J’s pronouns just before arriving for the weekend. It’s a moment in which Ghazvinizadeh nimbly navigates these two simultaneous explorations of identity, utilizing Araz’s language barrier to position him parallel to J.

The film ends in the most honest of ways, with continued ambiguity and no neat resolution. It mirrors the way identity often feels, cloudy and complicated and never as simple as the clear-cut decisions we’re asked to make. The whole film is dreamlike and static, and Ghazvinizadeh allows for exploration that reaches no ending but rather opens up each character to further nuance, complication and ultimately, acceptance.

Available to own or rent on digital HD.