LARRY STANTON

TEXT BY JULIAN KROLL

ARTWORK BY LARRY STANTON

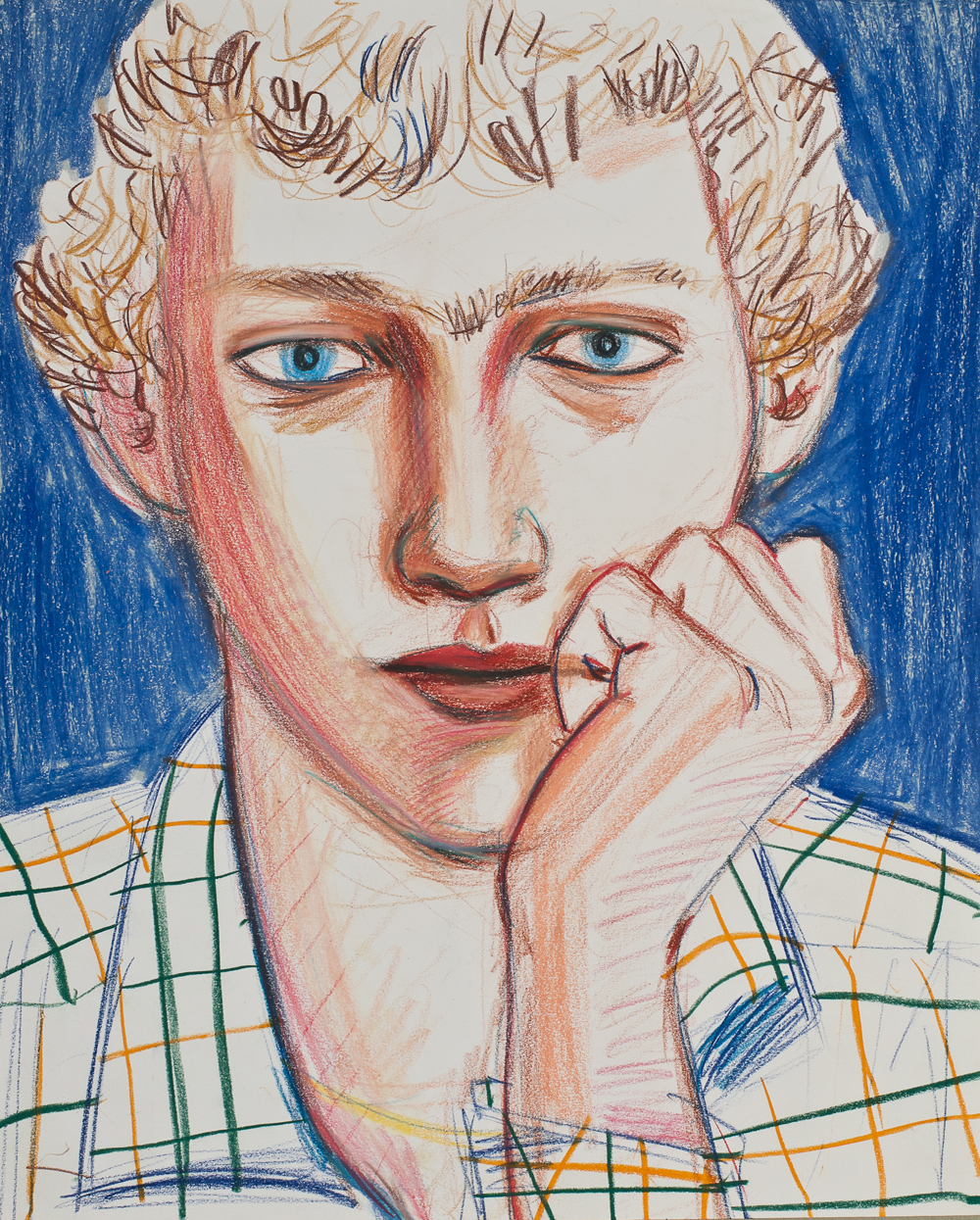

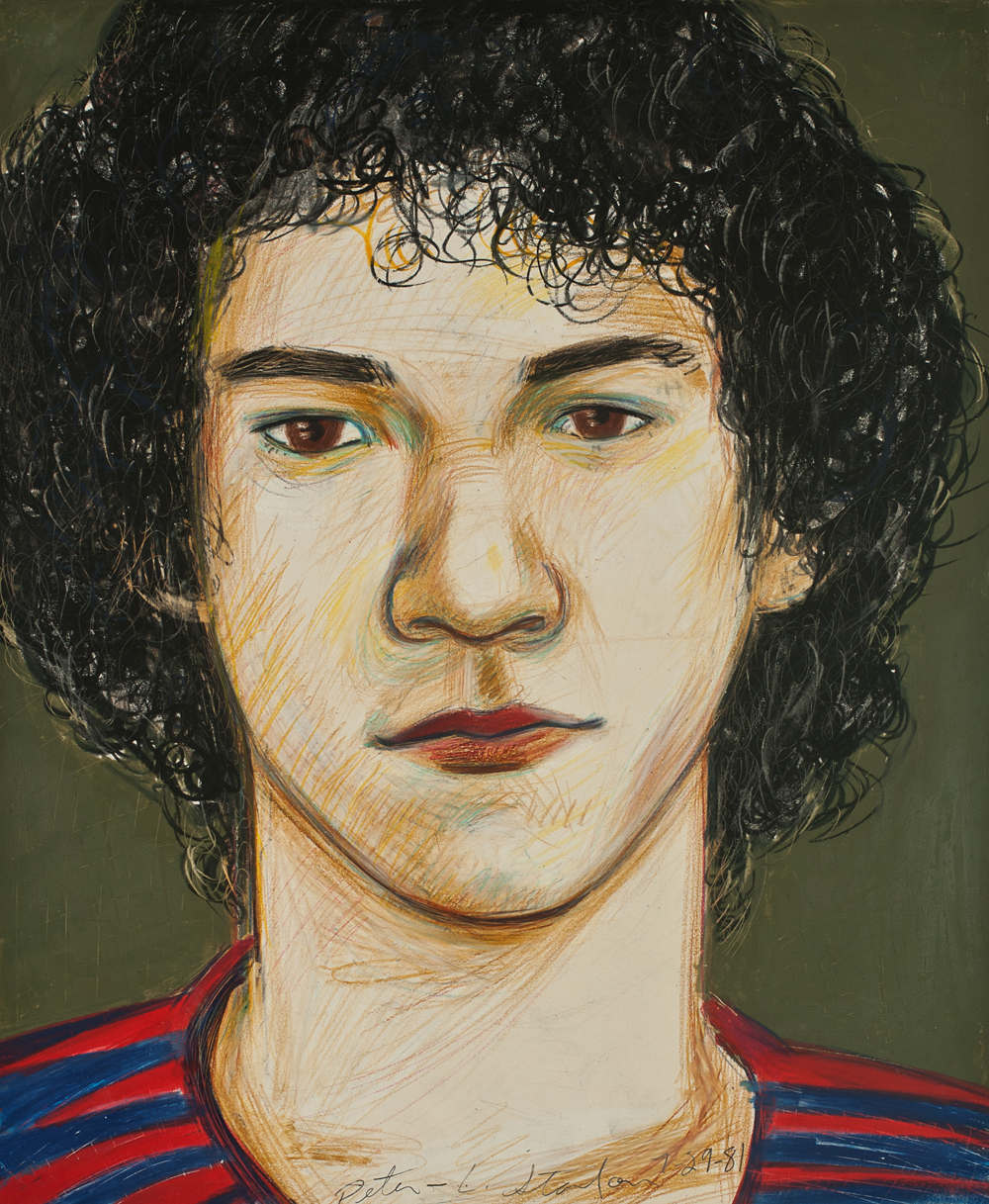

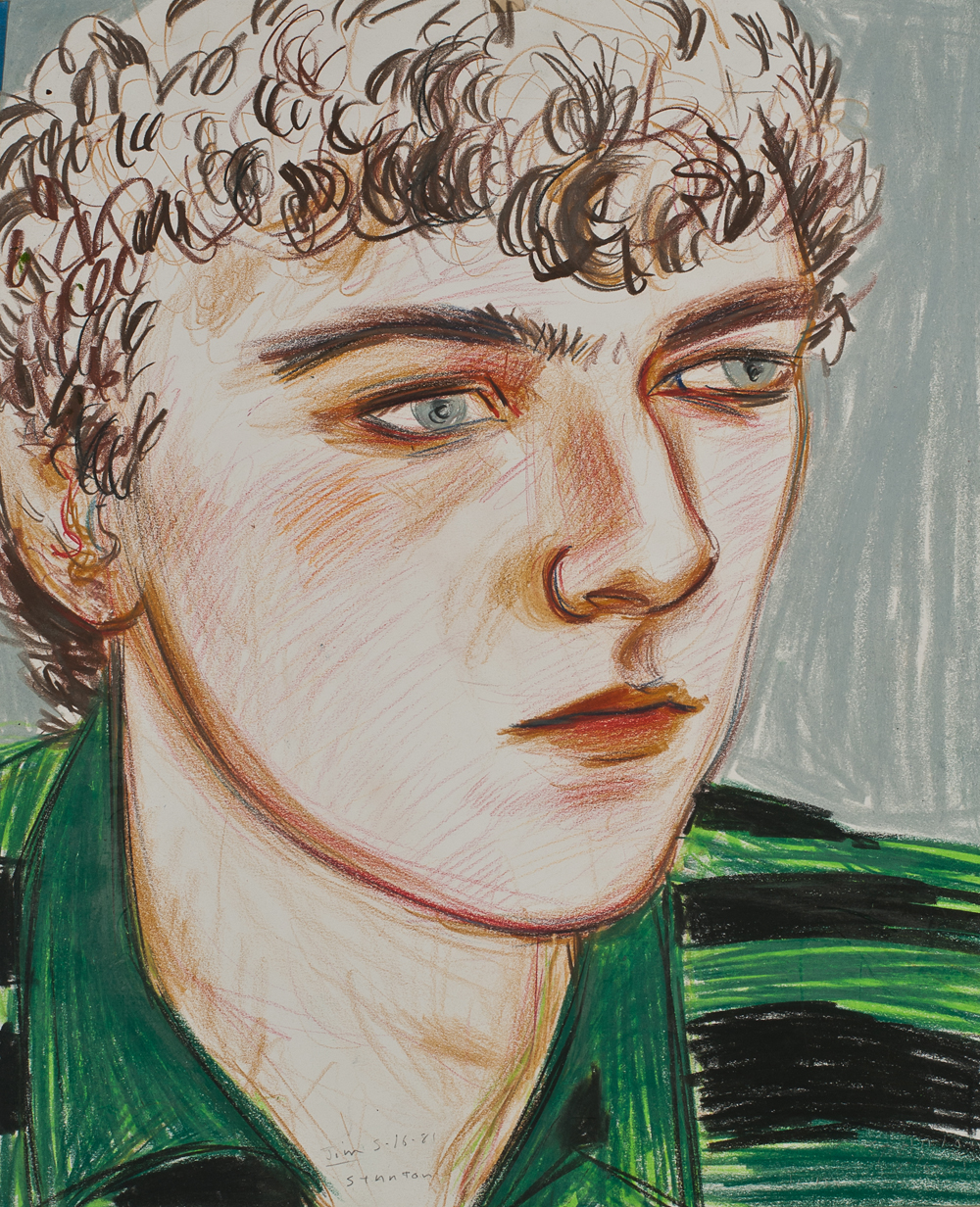

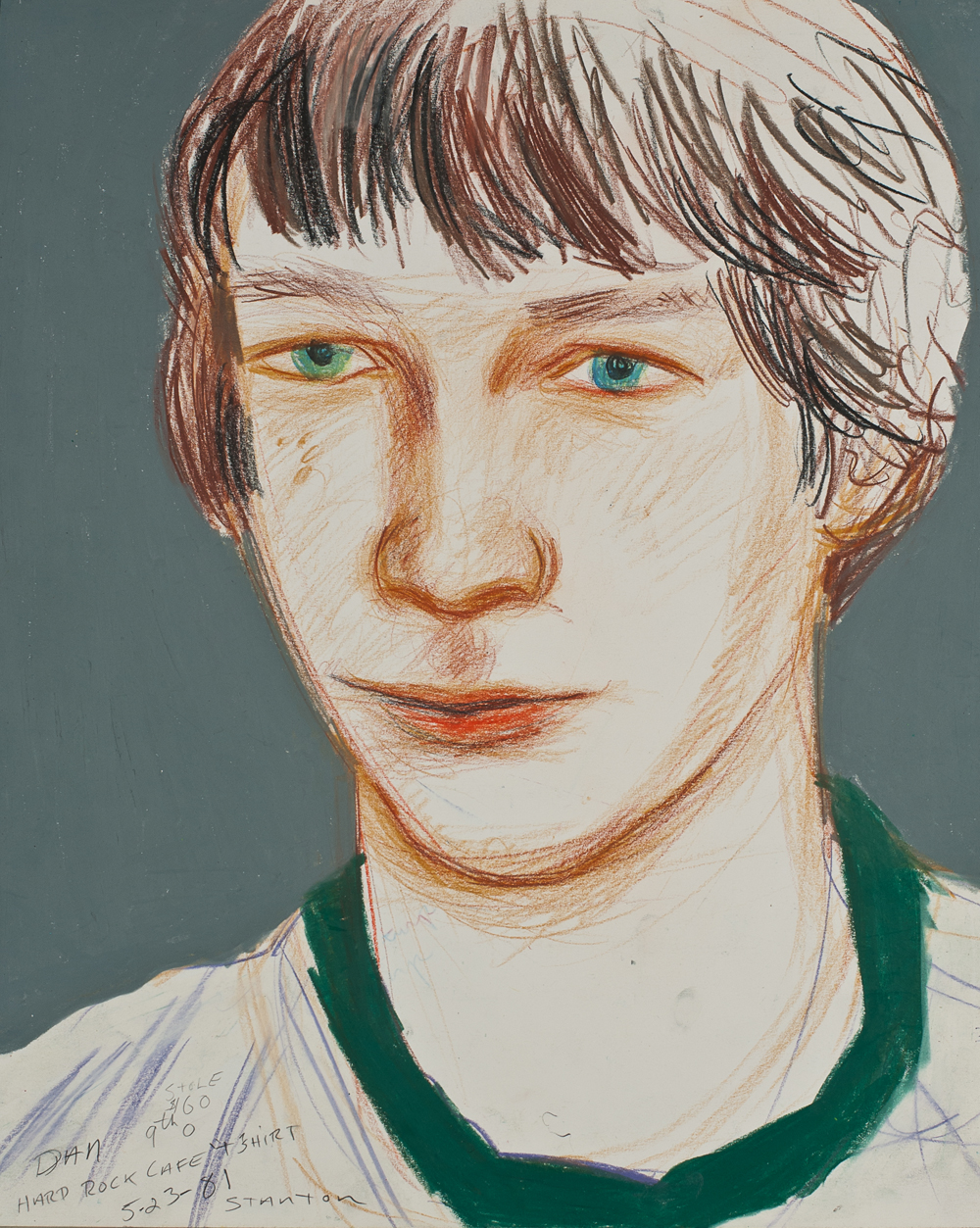

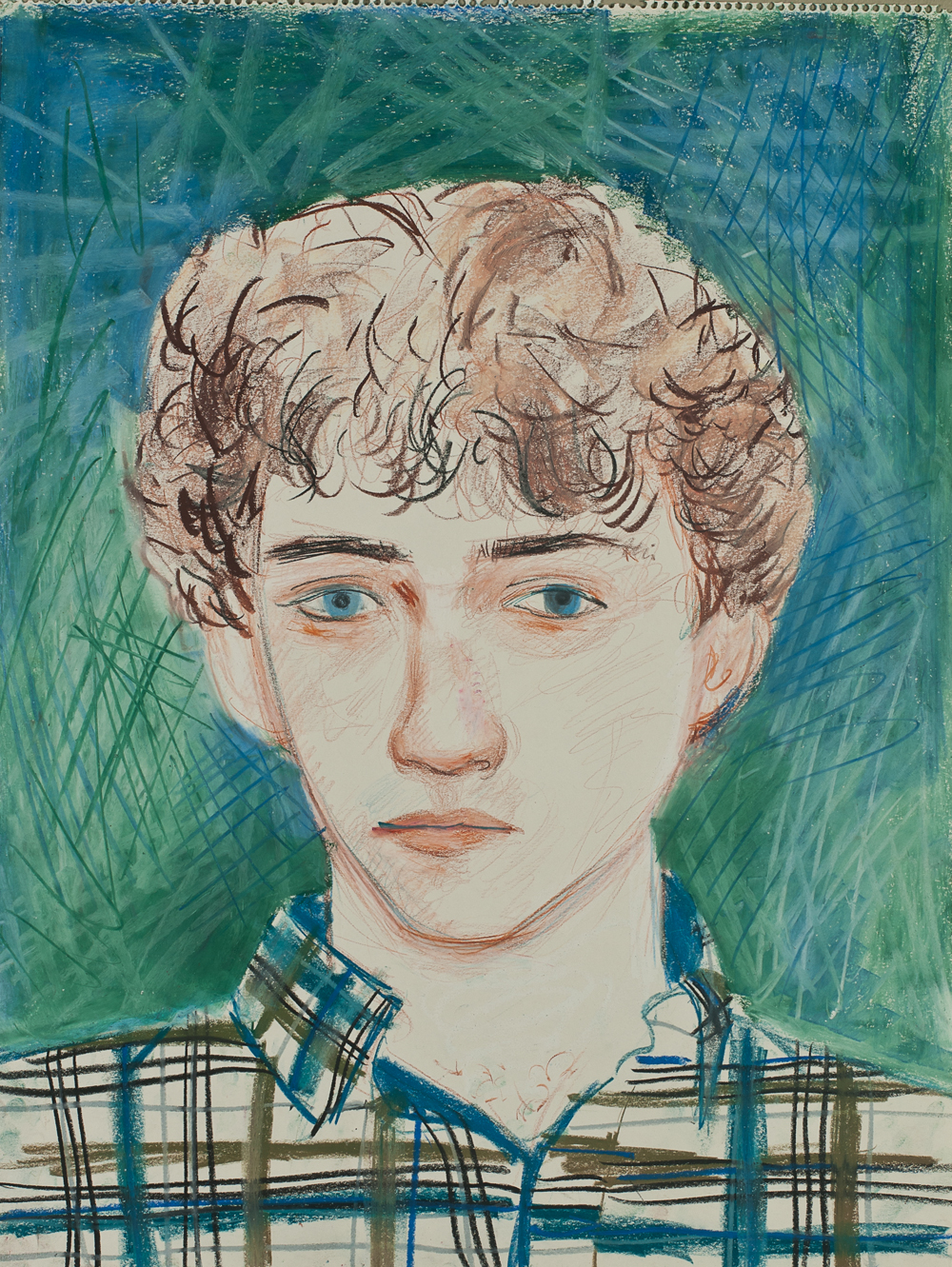

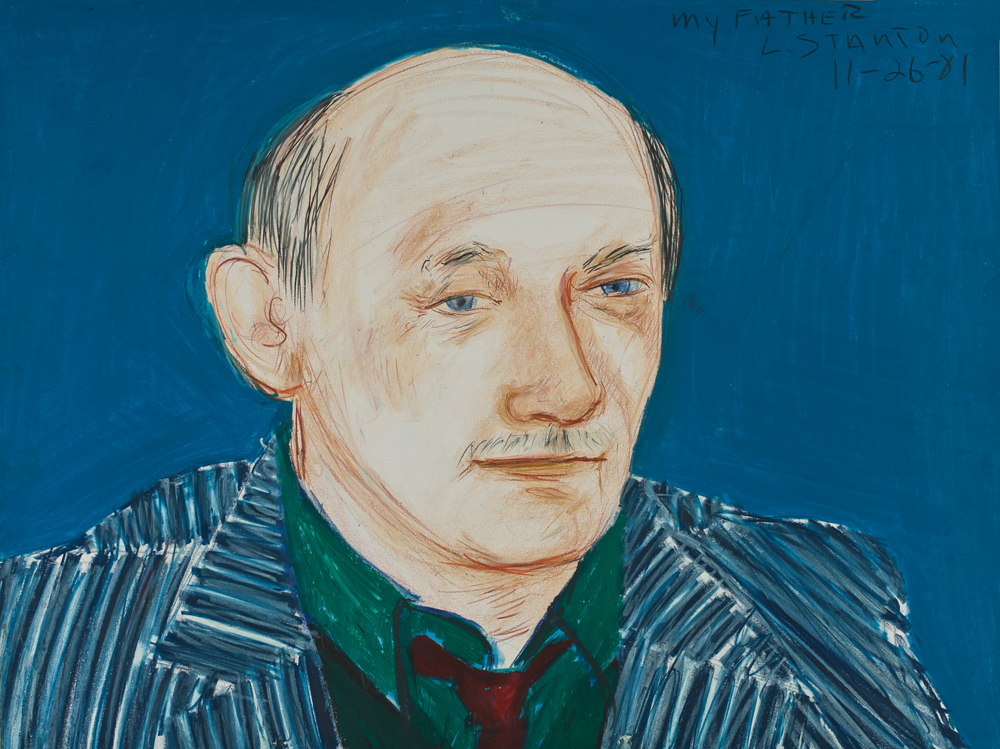

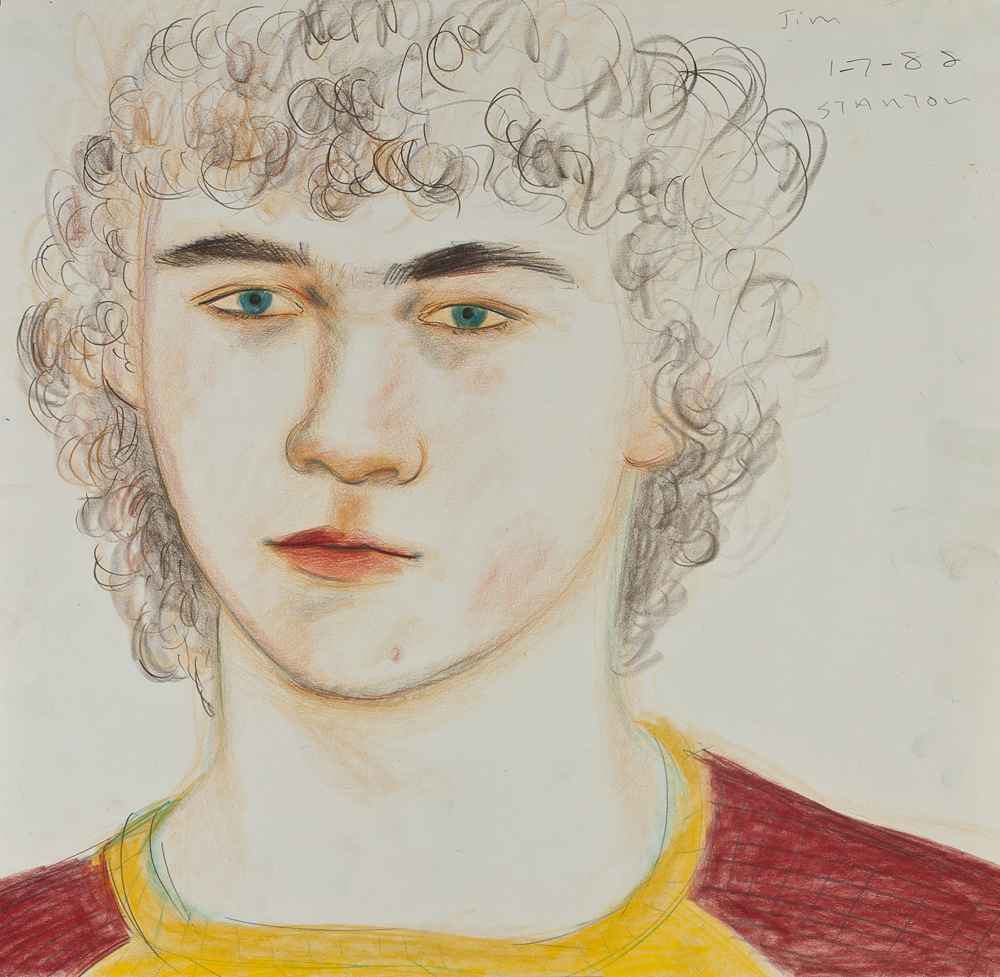

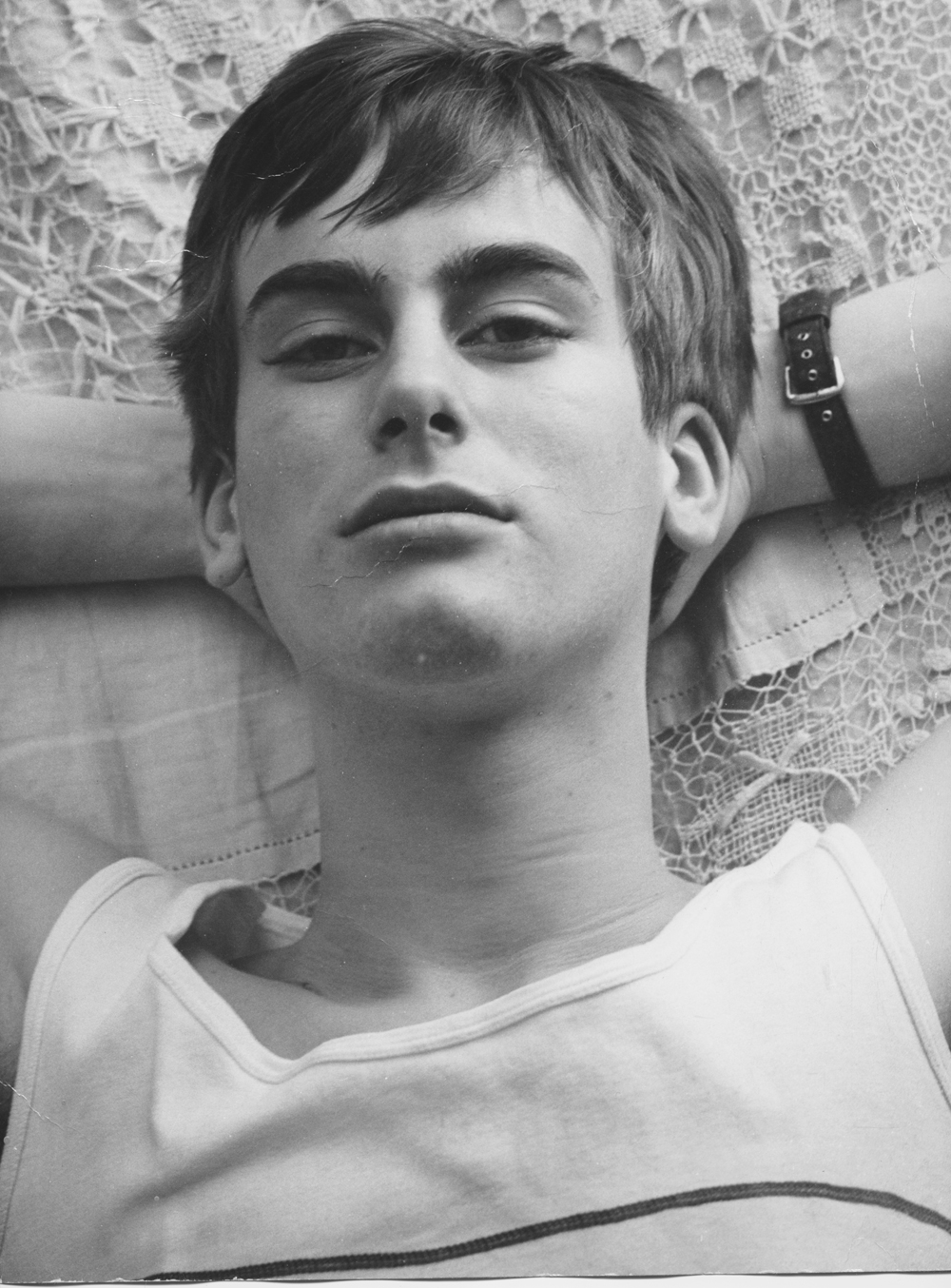

Larry Stanton was a portraitist. Raised on a dairy farm in the Catskills, he left home in 1966 to attend Cooper Union — though he dropped out after one semester. Over the following months working odd jobs in mailrooms and at ice cream parlors, he earned notoriety in gay New York for his striking looks and charm. By all accounts, he was worth the hype.

Among the men intrigued by Larry was banker Arthur Lambert. The two met in 1967, and were immediately drawn to each other. Shortly after meeting, the pair traveled to London and Los Angeles, where another stint in art school bolstered Larry’s creative ambitions.

During their travels, Larry also befriended painter David Hockney and curator Henry Geldzahler during his tenure at the Metropolitan Museum. Henry introduced Larry to the world of contemporary art and traveled with him to Italy and Tunisia.

Larry found his way back to New York in 1971. Working from a dingy basement studio in the Village, he sourced boys from local bars to model for portraits. Larry drew his subjects from direct observation, a technique which helped him to capture his models’ youthful energy. Coincidentally, it also made it easier to sleep with them. In 1979, however, his artistic prerogative was shaken by the death of his mother. His focus shifted from drawing to painting, and his work became more serious.

In 1984, at only 37, a series of ailments put Larry in the hospital, where he tested positive for HIV. With his partner Arthur by his bedside, Larry continued to make art through the first bedridden weeks. With each day, however, his breathing became more difficult. Four weeks after checking into the hospital, he passed away.

Through his work, Larry captured a generation of queer men soon to be lost. According to Arthur, “Most of the kids he drew disappeared in the AIDS plague, so his portraits are a collection of ghosts looking out at us, a testament to those who died, a memorial.”

“One day in the hospital,” Arthur recalls, “he tried to think of something which would cause me to remember him when he was gone and my memory of him had dimmed. After reflecting for a moment, he said, ‘I know, think of me when it thunders.’ It sounded like a good idea but it hasn’t worked out as we expected. It doesn’t thunder every day.”

All images courtesy of Larry Stanton Estate.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 13, get a copy here.

Larry Stanton was a portraitist. Raised on a dairy farm in the Catskills, he left home in 1966 to attend Cooper Union — though he dropped out after one semester. Over the following months working odd jobs in mailrooms and at ice cream parlors, he earned notoriety in gay New York for his striking looks and charm. By all accounts, he was worth the hype.

Among the men intrigued by Larry was banker Arthur Lambert. The two met in 1967, and were immediately drawn to each other. Shortly after meeting, the pair traveled to London and Los Angeles, where another stint in art school bolstered Larry’s creative ambitions.

During their travels, Larry also befriended painter David Hockney and curator Henry Geldzahler during his tenure at the Metropolitan Museum. Henry introduced Larry to the world of contemporary art and traveled with him to Italy and Tunisia.

Larry found his way back to New York in 1971. Working from a dingy basement studio in the Village, he sourced boys from local bars to model for portraits. Larry drew his subjects from direct observation, a technique which helped him to capture his models’ youthful energy. Coincidentally, it also made it easier to sleep with them. In 1979, however, his artistic prerogative was shaken by the death of his mother. His focus shifted from drawing to painting, and his work became more serious.

In 1984, at only 37, a series of ailments put Larry in the hospital, where he tested positive for HIV. With his partner Arthur by his bedside, Larry continued to make art through the first bedridden weeks. With each day, however, his breathing became more difficult. Four weeks after checking into the hospital, he passed away.

Through his work, Larry captured a generation of queer men soon to be lost. According to Arthur, “Most of the kids he drew disappeared in the AIDS plague, so his portraits are a collection of ghosts looking out at us, a testament to those who died, a memorial.”

“One day in the hospital,” Arthur recalls, “he tried to think of something which would cause me to remember him when he was gone and my memory of him had dimmed. After reflecting for a moment, he said, ‘I know, think of me when it thunders.’ It sounded like a good idea but it hasn’t worked out as we expected. It doesn’t thunder every day.”

All images courtesy of Larry Stanton Estate.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 13, get a copy here.

Larry Stanton was a portraitist. Raised on a dairy farm in the Catskills, he left home in 1966 to attend Cooper Union — though he dropped out after one semester. Over the following months working odd jobs in mailrooms and at ice cream parlors, he earned notoriety in gay New York for his striking looks and charm. By all accounts, he was worth the hype.

Among the men intrigued by Larry was banker Arthur Lambert. The two met in 1967, and were immediately drawn to each other. Shortly after meeting, the pair traveled to London and Los Angeles, where another stint in art school bolstered Larry’s creative ambitions.

During their travels, Larry also befriended painter David Hockney and curator Henry Geldzahler during his tenure at the Metropolitan Museum. Henry introduced Larry to the world of contemporary art and traveled with him to Italy and Tunisia.

Larry found his way back to New York in 1971. Working from a dingy basement studio in the Village, he sourced boys from local bars to model for portraits. Larry drew his subjects from direct observation, a technique which helped him to capture his models’ youthful energy. Coincidentally, it also made it easier to sleep with them. In 1979, however, his artistic prerogative was shaken by the death of his mother. His focus shifted from drawing to painting, and his work became more serious.

In 1984, at only 37, a series of ailments put Larry in the hospital, where he tested positive for HIV. With his partner Arthur by his bedside, Larry continued to make art through the first bedridden weeks. With each day, however, his breathing became more difficult. Four weeks after checking into the hospital, he passed away.

Through his work, Larry captured a generation of queer men soon to be lost. According to Arthur, “Most of the kids he drew disappeared in the AIDS plague, so his portraits are a collection of ghosts looking out at us, a testament to those who died, a memorial.”

“One day in the hospital,” Arthur recalls, “he tried to think of something which would cause me to remember him when he was gone and my memory of him had dimmed. After reflecting for a moment, he said, ‘I know, think of me when it thunders.’ It sounded like a good idea but it hasn’t worked out as we expected. It doesn’t thunder every day.”

All images courtesy of Larry Stanton Estate.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 13, get a copy here.

Larry Stanton was a portraitist. Raised on a dairy farm in the Catskills, he left home in 1966 to attend Cooper Union — though he dropped out after one semester. Over the following months working odd jobs in mailrooms and at ice cream parlors, he earned notoriety in gay New York for his striking looks and charm. By all accounts, he was worth the hype.

Among the men intrigued by Larry was banker Arthur Lambert. The two met in 1967, and were immediately drawn to each other. Shortly after meeting, the pair traveled to London and Los Angeles, where another stint in art school bolstered Larry’s creative ambitions.

During their travels, Larry also befriended painter David Hockney and curator Henry Geldzahler during his tenure at the Metropolitan Museum. Henry introduced Larry to the world of contemporary art and traveled with him to Italy and Tunisia.

Larry found his way back to New York in 1971. Working from a dingy basement studio in the Village, he sourced boys from local bars to model for portraits. Larry drew his subjects from direct observation, a technique which helped him to capture his models’ youthful energy. Coincidentally, it also made it easier to sleep with them. In 1979, however, his artistic prerogative was shaken by the death of his mother. His focus shifted from drawing to painting, and his work became more serious.

In 1984, at only 37, a series of ailments put Larry in the hospital, where he tested positive for HIV. With his partner Arthur by his bedside, Larry continued to make art through the first bedridden weeks. With each day, however, his breathing became more difficult. Four weeks after checking into the hospital, he passed away.

Through his work, Larry captured a generation of queer men soon to be lost. According to Arthur, “Most of the kids he drew disappeared in the AIDS plague, so his portraits are a collection of ghosts looking out at us, a testament to those who died, a memorial.”

“One day in the hospital,” Arthur recalls, “he tried to think of something which would cause me to remember him when he was gone and my memory of him had dimmed. After reflecting for a moment, he said, ‘I know, think of me when it thunders.’ It sounded like a good idea but it hasn’t worked out as we expected. It doesn’t thunder every day.”

All images courtesy of Larry Stanton Estate.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 13, get a copy here.

Larry Stanton was a portraitist. Raised on a dairy farm in the Catskills, he left home in 1966 to attend Cooper Union — though he dropped out after one semester. Over the following months working odd jobs in mailrooms and at ice cream parlors, he earned notoriety in gay New York for his striking looks and charm. By all accounts, he was worth the hype.

Among the men intrigued by Larry was banker Arthur Lambert. The two met in 1967, and were immediately drawn to each other. Shortly after meeting, the pair traveled to London and Los Angeles, where another stint in art school bolstered Larry’s creative ambitions.

During their travels, Larry also befriended painter David Hockney and curator Henry Geldzahler during his tenure at the Metropolitan Museum. Henry introduced Larry to the world of contemporary art and traveled with him to Italy and Tunisia.

Larry found his way back to New York in 1971. Working from a dingy basement studio in the Village, he sourced boys from local bars to model for portraits. Larry drew his subjects from direct observation, a technique which helped him to capture his models’ youthful energy. Coincidentally, it also made it easier to sleep with them. In 1979, however, his artistic prerogative was shaken by the death of his mother. His focus shifted from drawing to painting, and his work became more serious.

In 1984, at only 37, a series of ailments put Larry in the hospital, where he tested positive for HIV. With his partner Arthur by his bedside, Larry continued to make art through the first bedridden weeks. With each day, however, his breathing became more difficult. Four weeks after checking into the hospital, he passed away.

Through his work, Larry captured a generation of queer men soon to be lost. According to Arthur, “Most of the kids he drew disappeared in the AIDS plague, so his portraits are a collection of ghosts looking out at us, a testament to those who died, a memorial.”

“One day in the hospital,” Arthur recalls, “he tried to think of something which would cause me to remember him when he was gone and my memory of him had dimmed. After reflecting for a moment, he said, ‘I know, think of me when it thunders.’ It sounded like a good idea but it hasn’t worked out as we expected. It doesn’t thunder every day.”

All images courtesy of Larry Stanton Estate.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 13, get a copy here.

Larry Stanton was a portraitist. Raised on a dairy farm in the Catskills, he left home in 1966 to attend Cooper Union — though he dropped out after one semester. Over the following months working odd jobs in mailrooms and at ice cream parlors, he earned notoriety in gay New York for his striking looks and charm. By all accounts, he was worth the hype.

Among the men intrigued by Larry was banker Arthur Lambert. The two met in 1967, and were immediately drawn to each other. Shortly after meeting, the pair traveled to London and Los Angeles, where another stint in art school bolstered Larry’s creative ambitions.

During their travels, Larry also befriended painter David Hockney and curator Henry Geldzahler during his tenure at the Metropolitan Museum. Henry introduced Larry to the world of contemporary art and traveled with him to Italy and Tunisia.

Larry found his way back to New York in 1971. Working from a dingy basement studio in the Village, he sourced boys from local bars to model for portraits. Larry drew his subjects from direct observation, a technique which helped him to capture his models’ youthful energy. Coincidentally, it also made it easier to sleep with them. In 1979, however, his artistic prerogative was shaken by the death of his mother. His focus shifted from drawing to painting, and his work became more serious.

In 1984, at only 37, a series of ailments put Larry in the hospital, where he tested positive for HIV. With his partner Arthur by his bedside, Larry continued to make art through the first bedridden weeks. With each day, however, his breathing became more difficult. Four weeks after checking into the hospital, he passed away.

Through his work, Larry captured a generation of queer men soon to be lost. According to Arthur, “Most of the kids he drew disappeared in the AIDS plague, so his portraits are a collection of ghosts looking out at us, a testament to those who died, a memorial.”

“One day in the hospital,” Arthur recalls, “he tried to think of something which would cause me to remember him when he was gone and my memory of him had dimmed. After reflecting for a moment, he said, ‘I know, think of me when it thunders.’ It sounded like a good idea but it hasn’t worked out as we expected. It doesn’t thunder every day.”

All images courtesy of Larry Stanton Estate.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 13, get a copy here.

Larry Stanton was a portraitist. Raised on a dairy farm in the Catskills, he left home in 1966 to attend Cooper Union — though he dropped out after one semester. Over the following months working odd jobs in mailrooms and at ice cream parlors, he earned notoriety in gay New York for his striking looks and charm. By all accounts, he was worth the hype.

Among the men intrigued by Larry was banker Arthur Lambert. The two met in 1967, and were immediately drawn to each other. Shortly after meeting, the pair traveled to London and Los Angeles, where another stint in art school bolstered Larry’s creative ambitions.

During their travels, Larry also befriended painter David Hockney and curator Henry Geldzahler during his tenure at the Metropolitan Museum. Henry introduced Larry to the world of contemporary art and traveled with him to Italy and Tunisia.

Larry found his way back to New York in 1971. Working from a dingy basement studio in the Village, he sourced boys from local bars to model for portraits. Larry drew his subjects from direct observation, a technique which helped him to capture his models’ youthful energy. Coincidentally, it also made it easier to sleep with them. In 1979, however, his artistic prerogative was shaken by the death of his mother. His focus shifted from drawing to painting, and his work became more serious.

In 1984, at only 37, a series of ailments put Larry in the hospital, where he tested positive for HIV. With his partner Arthur by his bedside, Larry continued to make art through the first bedridden weeks. With each day, however, his breathing became more difficult. Four weeks after checking into the hospital, he passed away.

Through his work, Larry captured a generation of queer men soon to be lost. According to Arthur, “Most of the kids he drew disappeared in the AIDS plague, so his portraits are a collection of ghosts looking out at us, a testament to those who died, a memorial.”

“One day in the hospital,” Arthur recalls, “he tried to think of something which would cause me to remember him when he was gone and my memory of him had dimmed. After reflecting for a moment, he said, ‘I know, think of me when it thunders.’ It sounded like a good idea but it hasn’t worked out as we expected. It doesn’t thunder every day.”

All images courtesy of Larry Stanton Estate.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 13, get a copy here.

An image of Larry Stanton taken during his adolescence.

1/8