A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE NIPPLE PIERCING

TEXT BY SHIV KOTECHA

PHOTOGRAPHY BY DANIEL CAVANAUGH

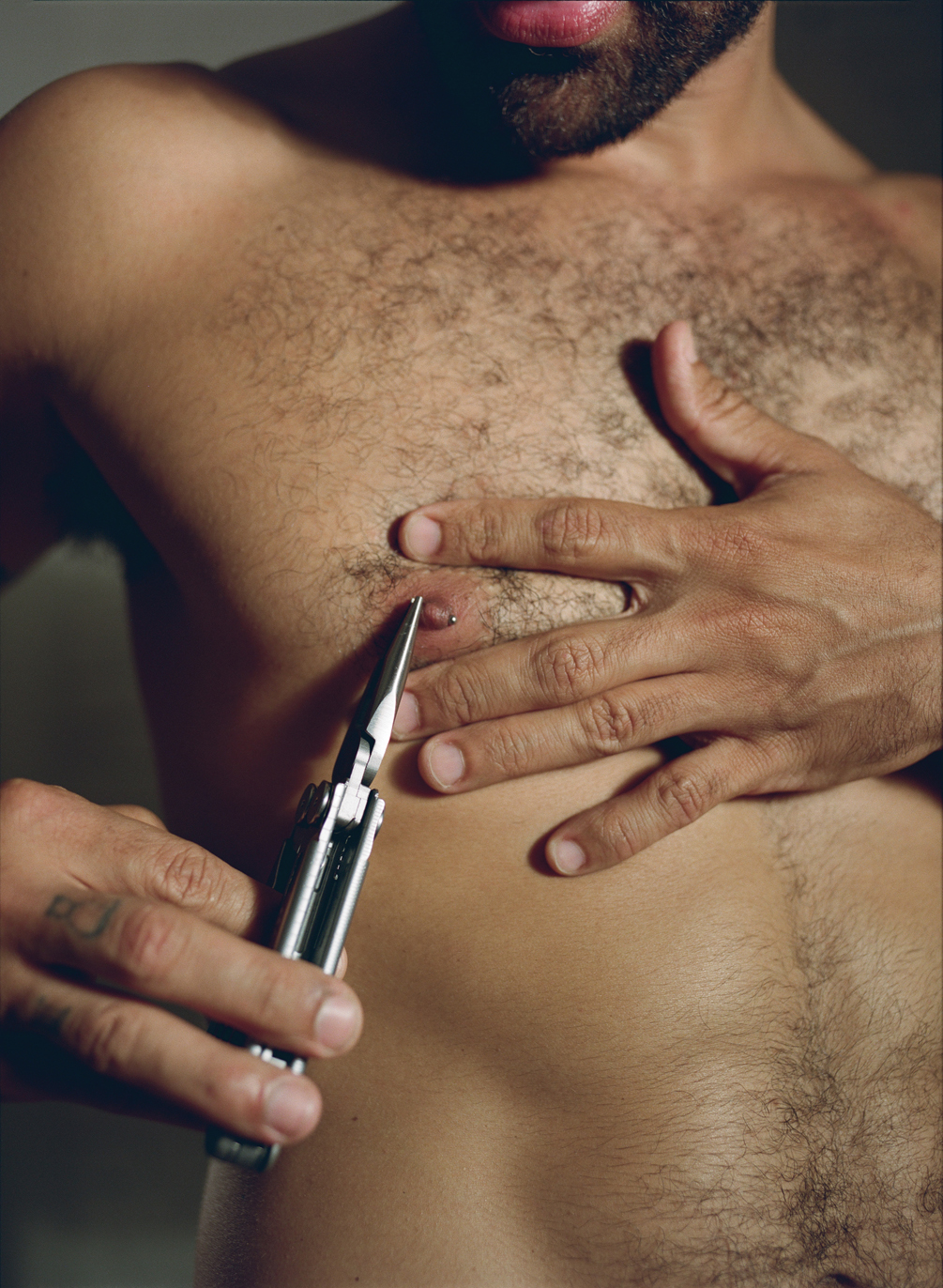

NIPPLE PIERCING BY BVLA.

That I feel as if I’ve outright lied to half of the people I have ever bedded about the sensitivity of my own nipples — careful! they’re far too sensitive, I’ve told some lovers; actually babe, I feel nothing, I’ve fibbed to others — suggests that, for potentially my entire sex life, I’ve mostly been lying to myself. Even now, as I graze a finger along one areolar region or pinch the raisin at the end of the other, I’m left wanting: is this enjoyment or pain?

It is advantageous, then, that the cosmos of feeling associated with the human nipple — for those unsatisfied with a simple flick or nibble, or by the effects of a more concentrated approach, as that of a twist, latch, or clamp — is just a piercing appointment away. Darting that extragenital chest flesh is an age-old tradition, performed by peoples across diverse cultures and genders, as a way to vanquish the ambivalence and insensitivity of an unlucky set of tits, and to secure them their right to be pleased.

Appropriately, there is no first pierced nipple; evidence appears in the annals of many civilizations, such as the North American Karankawa tribe, whose nomadic male subjects once roamed the coast of Southwest Texas with their nipples (and lips) horizontally spiked with long reeds of sugar cane that were, according to a first-hand account of the peoples by the Spanish colonizer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca from 1528, “as thick as two fingers.” In the Atlas Mountains in the northeast of Algeria, women native to the Kabyle tribe still pierce their nipples to demonstrate both their strength and their beauty.

The colonizers, too, held perennial interest in the trend. European historians trace nipple rings back to 9th-century Roman soldiers and to the tanned torsos of pirates and God-fearing seafarers alike. Anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr traces the nipple ring back to the 14th-century court of Isabeau of Bavaria, the queen consort of France, who adorned her breasts with diamond-studded hoops, gold chains, and ringlets of pearl. The tradition was again picked up with great fervor in fin-de-siècle Paris by society women willing to bear the pain of anneaux de sein for the promise of constant, ambient foreplay: “I found that the breasts of those who wore rings were incomparably rounder and fuller developed than those who did not,” wrote a certain Madame Beaumont, who underwent the procedure as a young woman while visiting the Paris Exhibition of 1889. “[They] are not in the least uncomfortable or painful,” she writes, “on the contrary, the slight rubbing and slipping of the rings causes in me an extremely titillating feeling, and all my colleagues to whom I have spoken on this subject have confirmed my opinion.”

It was Jim Ward, named “grandaddy of the modern body piercing movement,”who brought the trend stateside in the 1970s. Namely, he introduced American piercers to the barbell, a now common style of jewelry, which he lifted from the German designer Horst Streckenbach. In 1978, Ward would open the Gauntlet, a vanguard body-piercing studio in West Hollywood.

Though public figures like Rihanna, Tommy Lee, Kendall Jenner, and the abominable former Governor of New York State Andrew Cuomo have made a lasting case for the nipple piercing simply as fashion, its histories proffer a spectrum of functions that are hardly skin deep. But commitment remains key: for those who have opted in, healing time varies — twelve weeks is normal; up to a year should be expected. Common testimony also suggests that the tender skin spoked by the metal has the tendency to grow back over it, making the object difficult, if not impossible, to remove. It is a comfort to know that there’s pleasure in permanence, though there will always be some people who will refuse, fearing the pain of the procedure. To these gentle folk, I do not recommend love.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here.

SANDRO AND KEN BOTH WEAR THEIR OWN NIPPLE PIERCINGS.

That I feel as if I’ve outright lied to half of the people I have ever bedded about the sensitivity of my own nipples — careful! they’re far too sensitive, I’ve told some lovers; actually babe, I feel nothing, I’ve fibbed to others — suggests that, for potentially my entire sex life, I’ve mostly been lying to myself. Even now, as I graze a finger along one areolar region or pinch the raisin at the end of the other, I’m left wanting: is this enjoyment or pain?

It is advantageous, then, that the cosmos of feeling associated with the human nipple — for those unsatisfied with a simple flick or nibble, or by the effects of a more concentrated approach, as that of a twist, latch, or clamp — is just a piercing appointment away. Darting that extragenital chest flesh is an age-old tradition, performed by peoples across diverse cultures and genders, as a way to vanquish the ambivalence and insensitivity of an unlucky set of tits, and to secure them their right to be pleased.

Appropriately, there is no first pierced nipple; evidence appears in the annals of many civilizations, such as the North American Karankawa tribe, whose nomadic male subjects once roamed the coast of Southwest Texas with their nipples (and lips) horizontally spiked with long reeds of sugar cane that were, according to a first-hand account of the peoples by the Spanish colonizer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca from 1528, “as thick as two fingers.” In the Atlas Mountains in the northeast of Algeria, women native to the Kabyle tribe still pierce their nipples to demonstrate both their strength and their beauty.

The colonizers, too, held perennial interest in the trend. European historians trace nipple rings back to 9th-century Roman soldiers and to the tanned torsos of pirates and God-fearing seafarers alike. Anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr traces the nipple ring back to the 14th-century court of Isabeau of Bavaria, the queen consort of France, who adorned her breasts with diamond-studded hoops, gold chains, and ringlets of pearl. The tradition was again picked up with great fervor in fin-de-siècle Paris by society women willing to bear the pain of anneaux de sein for the promise of constant, ambient foreplay: “I found that the breasts of those who wore rings were incomparably rounder and fuller developed than those who did not,” wrote a certain Madame Beaumont, who underwent the procedure as a young woman while visiting the Paris Exhibition of 1889. “[They] are not in the least uncomfortable or painful,” she writes, “on the contrary, the slight rubbing and slipping of the rings causes in me an extremely titillating feeling, and all my colleagues to whom I have spoken on this subject have confirmed my opinion.”

It was Jim Ward, named “grandaddy of the modern body piercing movement,”who brought the trend stateside in the 1970s. Namely, he introduced American piercers to the barbell, a now common style of jewelry, which he lifted from the German designer Horst Streckenbach. In 1978, Ward would open the Gauntlet, a vanguard body-piercing studio in West Hollywood.

Though public figures like Rihanna, Tommy Lee, Kendall Jenner, and the abominable former Governor of New York State Andrew Cuomo have made a lasting case for the nipple piercing simply as fashion, its histories proffer a spectrum of functions that are hardly skin deep. But commitment remains key: for those who have opted in, healing time varies — twelve weeks is normal; up to a year should be expected. Common testimony also suggests that the tender skin spoked by the metal has the tendency to grow back over it, making the object difficult, if not impossible, to remove. It is a comfort to know that there’s pleasure in permanence, though there will always be some people who will refuse, fearing the pain of the procedure. To these gentle folk, I do not recommend love.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here.

NIPPLE PIERCING BY BVLA.

That I feel as if I’ve outright lied to half of the people I have ever bedded about the sensitivity of my own nipples — careful! they’re far too sensitive, I’ve told some lovers; actually babe, I feel nothing, I’ve fibbed to others — suggests that, for potentially my entire sex life, I’ve mostly been lying to myself. Even now, as I graze a finger along one areolar region or pinch the raisin at the end of the other, I’m left wanting: is this enjoyment or pain?

It is advantageous, then, that the cosmos of feeling associated with the human nipple — for those unsatisfied with a simple flick or nibble, or by the effects of a more concentrated approach, as that of a twist, latch, or clamp — is just a piercing appointment away. Darting that extragenital chest flesh is an age-old tradition, performed by peoples across diverse cultures and genders, as a way to vanquish the ambivalence and insensitivity of an unlucky set of tits, and to secure them their right to be pleased.

Appropriately, there is no first pierced nipple; evidence appears in the annals of many civilizations, such as the North American Karankawa tribe, whose nomadic male subjects once roamed the coast of Southwest Texas with their nipples (and lips) horizontally spiked with long reeds of sugar cane that were, according to a first-hand account of the peoples by the Spanish colonizer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca from 1528, “as thick as two fingers.” In the Atlas Mountains in the northeast of Algeria, women native to the Kabyle tribe still pierce their nipples to demonstrate both their strength and their beauty.

The colonizers, too, held perennial interest in the trend. European historians trace nipple rings back to 9th-century Roman soldiers and to the tanned torsos of pirates and God-fearing seafarers alike. Anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr traces the nipple ring back to the 14th-century court of Isabeau of Bavaria, the queen consort of France, who adorned her breasts with diamond-studded hoops, gold chains, and ringlets of pearl. The tradition was again picked up with great fervor in fin-de-siècle Paris by society women willing to bear the pain of anneaux de sein for the promise of constant, ambient foreplay: “I found that the breasts of those who wore rings were incomparably rounder and fuller developed than those who did not,” wrote a certain Madame Beaumont, who underwent the procedure as a young woman while visiting the Paris Exhibition of 1889. “[They] are not in the least uncomfortable or painful,” she writes, “on the contrary, the slight rubbing and slipping of the rings causes in me an extremely titillating feeling, and all my colleagues to whom I have spoken on this subject have confirmed my opinion.”

It was Jim Ward, named “grandaddy of the modern body piercing movement,”who brought the trend stateside in the 1970s. Namely, he introduced American piercers to the barbell, a now common style of jewelry, which he lifted from the German designer Horst Streckenbach. In 1978, Ward would open the Gauntlet, a vanguard body-piercing studio in West Hollywood.

Though public figures like Rihanna, Tommy Lee, Kendall Jenner, and the abominable former Governor of New York State Andrew Cuomo have made a lasting case for the nipple piercing simply as fashion, its histories proffer a spectrum of functions that are hardly skin deep. But commitment remains key: for those who have opted in, healing time varies — twelve weeks is normal; up to a year should be expected. Common testimony also suggests that the tender skin spoked by the metal has the tendency to grow back over it, making the object difficult, if not impossible, to remove. It is a comfort to know that there’s pleasure in permanence, though there will always be some people who will refuse, fearing the pain of the procedure. To these gentle folk, I do not recommend love.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here.

EARRING WORN AS PIERCING BY ALEXIS BITTAR.

That I feel as if I’ve outright lied to half of the people I have ever bedded about the sensitivity of my own nipples — careful! they’re far too sensitive, I’ve told some lovers; actually babe, I feel nothing, I’ve fibbed to others — suggests that, for potentially my entire sex life, I’ve mostly been lying to myself. Even now, as I graze a finger along one areolar region or pinch the raisin at the end of the other, I’m left wanting: is this enjoyment or pain?

It is advantageous, then, that the cosmos of feeling associated with the human nipple — for those unsatisfied with a simple flick or nibble, or by the effects of a more concentrated approach, as that of a twist, latch, or clamp — is just a piercing appointment away. Darting that extragenital chest flesh is an age-old tradition, performed by peoples across diverse cultures and genders, as a way to vanquish the ambivalence and insensitivity of an unlucky set of tits, and to secure them their right to be pleased.

Appropriately, there is no first pierced nipple; evidence appears in the annals of many civilizations, such as the North American Karankawa tribe, whose nomadic male subjects once roamed the coast of Southwest Texas with their nipples (and lips) horizontally spiked with long reeds of sugar cane that were, according to a first-hand account of the peoples by the Spanish colonizer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca from 1528, “as thick as two fingers.” In the Atlas Mountains in the northeast of Algeria, women native to the Kabyle tribe still pierce their nipples to demonstrate both their strength and their beauty.

The colonizers, too, held perennial interest in the trend. European historians trace nipple rings back to 9th-century Roman soldiers and to the tanned torsos of pirates and God-fearing seafarers alike. Anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr traces the nipple ring back to the 14th-century court of Isabeau of Bavaria, the queen consort of France, who adorned her breasts with diamond-studded hoops, gold chains, and ringlets of pearl. The tradition was again picked up with great fervor in fin-de-siècle Paris by society women willing to bear the pain of anneaux de sein for the promise of constant, ambient foreplay: “I found that the breasts of those who wore rings were incomparably rounder and fuller developed than those who did not,” wrote a certain Madame Beaumont, who underwent the procedure as a young woman while visiting the Paris Exhibition of 1889. “[They] are not in the least uncomfortable or painful,” she writes, “on the contrary, the slight rubbing and slipping of the rings causes in me an extremely titillating feeling, and all my colleagues to whom I have spoken on this subject have confirmed my opinion.”

It was Jim Ward, named “grandaddy of the modern body piercing movement,”who brought the trend stateside in the 1970s. Namely, he introduced American piercers to the barbell, a now common style of jewelry, which he lifted from the German designer Horst Streckenbach. In 1978, Ward would open the Gauntlet, a vanguard body-piercing studio in West Hollywood.

Though public figures like Rihanna, Tommy Lee, Kendall Jenner, and the abominable former Governor of New York State Andrew Cuomo have made a lasting case for the nipple piercing simply as fashion, its histories proffer a spectrum of functions that are hardly skin deep. But commitment remains key: for those who have opted in, healing time varies — twelve weeks is normal; up to a year should be expected. Common testimony also suggests that the tender skin spoked by the metal has the tendency to grow back over it, making the object difficult, if not impossible, to remove. It is a comfort to know that there’s pleasure in permanence, though there will always be some people who will refuse, fearing the pain of the procedure. To these gentle folk, I do not recommend love.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here.

LUCKY WEARS HIS OWN NIPPLE PIERCING.

That I feel as if I’ve outright lied to half of the people I have ever bedded about the sensitivity of my own nipples — careful! they’re far too sensitive, I’ve told some lovers; actually babe, I feel nothing, I’ve fibbed to others — suggests that, for potentially my entire sex life, I’ve mostly been lying to myself. Even now, as I graze a finger along one areolar region or pinch the raisin at the end of the other, I’m left wanting: is this enjoyment or pain?

It is advantageous, then, that the cosmos of feeling associated with the human nipple — for those unsatisfied with a simple flick or nibble, or by the effects of a more concentrated approach, as that of a twist, latch, or clamp — is just a piercing appointment away. Darting that extragenital chest flesh is an age-old tradition, performed by peoples across diverse cultures and genders, as a way to vanquish the ambivalence and insensitivity of an unlucky set of tits, and to secure them their right to be pleased.

Appropriately, there is no first pierced nipple; evidence appears in the annals of many civilizations, such as the North American Karankawa tribe, whose nomadic male subjects once roamed the coast of Southwest Texas with their nipples (and lips) horizontally spiked with long reeds of sugar cane that were, according to a first-hand account of the peoples by the Spanish colonizer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca from 1528, “as thick as two fingers.” In the Atlas Mountains in the northeast of Algeria, women native to the Kabyle tribe still pierce their nipples to demonstrate both their strength and their beauty.

The colonizers, too, held perennial interest in the trend. European historians trace nipple rings back to 9th-century Roman soldiers and to the tanned torsos of pirates and God-fearing seafarers alike. Anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr traces the nipple ring back to the 14th-century court of Isabeau of Bavaria, the queen consort of France, who adorned her breasts with diamond-studded hoops, gold chains, and ringlets of pearl. The tradition was again picked up with great fervor in fin-de-siècle Paris by society women willing to bear the pain of anneaux de sein for the promise of constant, ambient foreplay: “I found that the breasts of those who wore rings were incomparably rounder and fuller developed than those who did not,” wrote a certain Madame Beaumont, who underwent the procedure as a young woman while visiting the Paris Exhibition of 1889. “[They] are not in the least uncomfortable or painful,” she writes, “on the contrary, the slight rubbing and slipping of the rings causes in me an extremely titillating feeling, and all my colleagues to whom I have spoken on this subject have confirmed my opinion.”

It was Jim Ward, named “grandaddy of the modern body piercing movement,”who brought the trend stateside in the 1970s. Namely, he introduced American piercers to the barbell, a now common style of jewelry, which he lifted from the German designer Horst Streckenbach. In 1978, Ward would open the Gauntlet, a vanguard body-piercing studio in West Hollywood.

Though public figures like Rihanna, Tommy Lee, Kendall Jenner, and the abominable former Governor of New York State Andrew Cuomo have made a lasting case for the nipple piercing simply as fashion, its histories proffer a spectrum of functions that are hardly skin deep. But commitment remains key: for those who have opted in, healing time varies — twelve weeks is normal; up to a year should be expected. Common testimony also suggests that the tender skin spoked by the metal has the tendency to grow back over it, making the object difficult, if not impossible, to remove. It is a comfort to know that there’s pleasure in permanence, though there will always be some people who will refuse, fearing the pain of the procedure. To these gentle folk, I do not recommend love.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here.

GUSTAVO WEARS HIS OWN NIPPLE PIERCING.

That I feel as if I’ve outright lied to half of the people I have ever bedded about the sensitivity of my own nipples — careful! they’re far too sensitive, I’ve told some lovers; actually babe, I feel nothing, I’ve fibbed to others — suggests that, for potentially my entire sex life, I’ve mostly been lying to myself. Even now, as I graze a finger along one areolar region or pinch the raisin at the end of the other, I’m left wanting: is this enjoyment or pain?

It is advantageous, then, that the cosmos of feeling associated with the human nipple — for those unsatisfied with a simple flick or nibble, or by the effects of a more concentrated approach, as that of a twist, latch, or clamp — is just a piercing appointment away. Darting that extragenital chest flesh is an age-old tradition, performed by peoples across diverse cultures and genders, as a way to vanquish the ambivalence and insensitivity of an unlucky set of tits, and to secure them their right to be pleased.

Appropriately, there is no first pierced nipple; evidence appears in the annals of many civilizations, such as the North American Karankawa tribe, whose nomadic male subjects once roamed the coast of Southwest Texas with their nipples (and lips) horizontally spiked with long reeds of sugar cane that were, according to a first-hand account of the peoples by the Spanish colonizer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca from 1528, “as thick as two fingers.” In the Atlas Mountains in the northeast of Algeria, women native to the Kabyle tribe still pierce their nipples to demonstrate both their strength and their beauty.

The colonizers, too, held perennial interest in the trend. European historians trace nipple rings back to 9th-century Roman soldiers and to the tanned torsos of pirates and God-fearing seafarers alike. Anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr traces the nipple ring back to the 14th-century court of Isabeau of Bavaria, the queen consort of France, who adorned her breasts with diamond-studded hoops, gold chains, and ringlets of pearl. The tradition was again picked up with great fervor in fin-de-siècle Paris by society women willing to bear the pain of anneaux de sein for the promise of constant, ambient foreplay: “I found that the breasts of those who wore rings were incomparably rounder and fuller developed than those who did not,” wrote a certain Madame Beaumont, who underwent the procedure as a young woman while visiting the Paris Exhibition of 1889. “[They] are not in the least uncomfortable or painful,” she writes, “on the contrary, the slight rubbing and slipping of the rings causes in me an extremely titillating feeling, and all my colleagues to whom I have spoken on this subject have confirmed my opinion.”

It was Jim Ward, named “grandaddy of the modern body piercing movement,”who brought the trend stateside in the 1970s. Namely, he introduced American piercers to the barbell, a now common style of jewelry, which he lifted from the German designer Horst Streckenbach. In 1978, Ward would open the Gauntlet, a vanguard body-piercing studio in West Hollywood.

Though public figures like Rihanna, Tommy Lee, Kendall Jenner, and the abominable former Governor of New York State Andrew Cuomo have made a lasting case for the nipple piercing simply as fashion, its histories proffer a spectrum of functions that are hardly skin deep. But commitment remains key: for those who have opted in, healing time varies — twelve weeks is normal; up to a year should be expected. Common testimony also suggests that the tender skin spoked by the metal has the tendency to grow back over it, making the object difficult, if not impossible, to remove. It is a comfort to know that there’s pleasure in permanence, though there will always be some people who will refuse, fearing the pain of the procedure. To these gentle folk, I do not recommend love.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here.

Gustavo was pierced in May, 2008.

That I feel as if I’ve outright lied to half of the people I have ever bedded about the sensitivity of my own nipples — careful! they’re far too sensitive, I’ve told some lovers; actually babe, I feel nothing, I’ve fibbed to others — suggests that, for potentially my entire sex life, I’ve mostly been lying to myself. Even now, as I graze a finger along one areolar region or pinch the raisin at the end of the other, I’m left wanting: is this enjoyment or pain?

It is advantageous, then, that the cosmos of feeling associated with the human nipple — for those unsatisfied with a simple flick or nibble, or by the effects of a more concentrated approach, as that of a twist, latch, or clamp — is just a piercing appointment away. Darting that extragenital chest flesh is an age-old tradition, performed by peoples across diverse cultures and genders, as a way to vanquish the ambivalence and insensitivity of an unlucky set of tits, and to secure them their right to be pleased.

Appropriately, there is no first pierced nipple; evidence appears in the annals of many civilizations, such as the North American Karankawa tribe, whose nomadic male subjects once roamed the coast of Southwest Texas with their nipples (and lips) horizontally spiked with long reeds of sugar cane that were, according to a first-hand account of the peoples by the Spanish colonizer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca from 1528, “as thick as two fingers.” In the Atlas Mountains in the northeast of Algeria, women native to the Kabyle tribe still pierce their nipples to demonstrate both their strength and their beauty.

The colonizers, too, held perennial interest in the trend. European historians trace nipple rings back to 9th-century Roman soldiers and to the tanned torsos of pirates and God-fearing seafarers alike. Anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr traces the nipple ring back to the 14th-century court of Isabeau of Bavaria, the queen consort of France, who adorned her breasts with diamond-studded hoops, gold chains, and ringlets of pearl. The tradition was again picked up with great fervor in fin-de-siècle Paris by society women willing to bear the pain of anneaux de sein for the promise of constant, ambient foreplay: “I found that the breasts of those who wore rings were incomparably rounder and fuller developed than those who did not,” wrote a certain Madame Beaumont, who underwent the procedure as a young woman while visiting the Paris Exhibition of 1889. “[They] are not in the least uncomfortable or painful,” she writes, “on the contrary, the slight rubbing and slipping of the rings causes in me an extremely titillating feeling, and all my colleagues to whom I have spoken on this subject have confirmed my opinion.”

It was Jim Ward, named “grandaddy of the modern body piercing movement,”who brought the trend stateside in the 1970s. Namely, he introduced American piercers to the barbell, a now common style of jewelry, which he lifted from the German designer Horst Streckenbach. In 1978, Ward would open the Gauntlet, a vanguard body-piercing studio in West Hollywood.

Though public figures like Rihanna, Tommy Lee, Kendall Jenner, and the abominable former Governor of New York State Andrew Cuomo have made a lasting case for the nipple piercing simply as fashion, its histories proffer a spectrum of functions that are hardly skin deep. But commitment remains key: for those who have opted in, healing time varies — twelve weeks is normal; up to a year should be expected. Common testimony also suggests that the tender skin spoked by the metal has the tendency to grow back over it, making the object difficult, if not impossible, to remove. It is a comfort to know that there’s pleasure in permanence, though there will always be some people who will refuse, fearing the pain of the procedure. To these gentle folk, I do not recommend love.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here.

Sandro was pierced in February, 2022.

That I feel as if I’ve outright lied to half of the people I have ever bedded about the sensitivity of my own nipples — careful! they’re far too sensitive, I’ve told some lovers; actually babe, I feel nothing, I’ve fibbed to others — suggests that, for potentially my entire sex life, I’ve mostly been lying to myself. Even now, as I graze a finger along one areolar region or pinch the raisin at the end of the other, I’m left wanting: is this enjoyment or pain?

It is advantageous, then, that the cosmos of feeling associated with the human nipple — for those unsatisfied with a simple flick or nibble, or by the effects of a more concentrated approach, as that of a twist, latch, or clamp — is just a piercing appointment away. Darting that extragenital chest flesh is an age-old tradition, performed by peoples across diverse cultures and genders, as a way to vanquish the ambivalence and insensitivity of an unlucky set of tits, and to secure them their right to be pleased.

Appropriately, there is no first pierced nipple; evidence appears in the annals of many civilizations, such as the North American Karankawa tribe, whose nomadic male subjects once roamed the coast of Southwest Texas with their nipples (and lips) horizontally spiked with long reeds of sugar cane that were, according to a first-hand account of the peoples by the Spanish colonizer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca from 1528, “as thick as two fingers.” In the Atlas Mountains in the northeast of Algeria, women native to the Kabyle tribe still pierce their nipples to demonstrate both their strength and their beauty.

The colonizers, too, held perennial interest in the trend. European historians trace nipple rings back to 9th-century Roman soldiers and to the tanned torsos of pirates and God-fearing seafarers alike. Anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr traces the nipple ring back to the 14th-century court of Isabeau of Bavaria, the queen consort of France, who adorned her breasts with diamond-studded hoops, gold chains, and ringlets of pearl. The tradition was again picked up with great fervor in fin-de-siècle Paris by society women willing to bear the pain of anneaux de sein for the promise of constant, ambient foreplay: “I found that the breasts of those who wore rings were incomparably rounder and fuller developed than those who did not,” wrote a certain Madame Beaumont, who underwent the procedure as a young woman while visiting the Paris Exhibition of 1889. “[They] are not in the least uncomfortable or painful,” she writes, “on the contrary, the slight rubbing and slipping of the rings causes in me an extremely titillating feeling, and all my colleagues to whom I have spoken on this subject have confirmed my opinion.”

It was Jim Ward, named “grandaddy of the modern body piercing movement,”who brought the trend stateside in the 1970s. Namely, he introduced American piercers to the barbell, a now common style of jewelry, which he lifted from the German designer Horst Streckenbach. In 1978, Ward would open the Gauntlet, a vanguard body-piercing studio in West Hollywood.

Though public figures like Rihanna, Tommy Lee, Kendall Jenner, and the abominable former Governor of New York State Andrew Cuomo have made a lasting case for the nipple piercing simply as fashion, its histories proffer a spectrum of functions that are hardly skin deep. But commitment remains key: for those who have opted in, healing time varies — twelve weeks is normal; up to a year should be expected. Common testimony also suggests that the tender skin spoked by the metal has the tendency to grow back over it, making the object difficult, if not impossible, to remove. It is a comfort to know that there’s pleasure in permanence, though there will always be some people who will refuse, fearing the pain of the procedure. To these gentle folk, I do not recommend love.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here.

Ken was pierced in February, 2022.

That I feel as if I’ve outright lied to half of the people I have ever bedded about the sensitivity of my own nipples — careful! they’re far too sensitive, I’ve told some lovers; actually babe, I feel nothing, I’ve fibbed to others — suggests that, for potentially my entire sex life, I’ve mostly been lying to myself. Even now, as I graze a finger along one areolar region or pinch the raisin at the end of the other, I’m left wanting: is this enjoyment or pain?

It is advantageous, then, that the cosmos of feeling associated with the human nipple — for those unsatisfied with a simple flick or nibble, or by the effects of a more concentrated approach, as that of a twist, latch, or clamp — is just a piercing appointment away. Darting that extragenital chest flesh is an age-old tradition, performed by peoples across diverse cultures and genders, as a way to vanquish the ambivalence and insensitivity of an unlucky set of tits, and to secure them their right to be pleased.

Appropriately, there is no first pierced nipple; evidence appears in the annals of many civilizations, such as the North American Karankawa tribe, whose nomadic male subjects once roamed the coast of Southwest Texas with their nipples (and lips) horizontally spiked with long reeds of sugar cane that were, according to a first-hand account of the peoples by the Spanish colonizer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca from 1528, “as thick as two fingers.” In the Atlas Mountains in the northeast of Algeria, women native to the Kabyle tribe still pierce their nipples to demonstrate both their strength and their beauty.

The colonizers, too, held perennial interest in the trend. European historians trace nipple rings back to 9th-century Roman soldiers and to the tanned torsos of pirates and God-fearing seafarers alike. Anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr traces the nipple ring back to the 14th-century court of Isabeau of Bavaria, the queen consort of France, who adorned her breasts with diamond-studded hoops, gold chains, and ringlets of pearl. The tradition was again picked up with great fervor in fin-de-siècle Paris by society women willing to bear the pain of anneaux de sein for the promise of constant, ambient foreplay: “I found that the breasts of those who wore rings were incomparably rounder and fuller developed than those who did not,” wrote a certain Madame Beaumont, who underwent the procedure as a young woman while visiting the Paris Exhibition of 1889. “[They] are not in the least uncomfortable or painful,” she writes, “on the contrary, the slight rubbing and slipping of the rings causes in me an extremely titillating feeling, and all my colleagues to whom I have spoken on this subject have confirmed my opinion.”

It was Jim Ward, named “grandaddy of the modern body piercing movement,”who brought the trend stateside in the 1970s. Namely, he introduced American piercers to the barbell, a now common style of jewelry, which he lifted from the German designer Horst Streckenbach. In 1978, Ward would open the Gauntlet, a vanguard body-piercing studio in West Hollywood.

Though public figures like Rihanna, Tommy Lee, Kendall Jenner, and the abominable former Governor of New York State Andrew Cuomo have made a lasting case for the nipple piercing simply as fashion, its histories proffer a spectrum of functions that are hardly skin deep. But commitment remains key: for those who have opted in, healing time varies — twelve weeks is normal; up to a year should be expected. Common testimony also suggests that the tender skin spoked by the metal has the tendency to grow back over it, making the object difficult, if not impossible, to remove. It is a comfort to know that there’s pleasure in permanence, though there will always be some people who will refuse, fearing the pain of the procedure. To these gentle folk, I do not recommend love.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here.

Lucky was pierced in May, 2019.

That I feel as if I’ve outright lied to half of the people I have ever bedded about the sensitivity of my own nipples — careful! they’re far too sensitive, I’ve told some lovers; actually babe, I feel nothing, I’ve fibbed to others — suggests that, for potentially my entire sex life, I’ve mostly been lying to myself. Even now, as I graze a finger along one areolar region or pinch the raisin at the end of the other, I’m left wanting: is this enjoyment or pain?

It is advantageous, then, that the cosmos of feeling associated with the human nipple — for those unsatisfied with a simple flick or nibble, or by the effects of a more concentrated approach, as that of a twist, latch, or clamp — is just a piercing appointment away. Darting that extragenital chest flesh is an age-old tradition, performed by peoples across diverse cultures and genders, as a way to vanquish the ambivalence and insensitivity of an unlucky set of tits, and to secure them their right to be pleased.

Appropriately, there is no first pierced nipple; evidence appears in the annals of many civilizations, such as the North American Karankawa tribe, whose nomadic male subjects once roamed the coast of Southwest Texas with their nipples (and lips) horizontally spiked with long reeds of sugar cane that were, according to a first-hand account of the peoples by the Spanish colonizer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca from 1528, “as thick as two fingers.” In the Atlas Mountains in the northeast of Algeria, women native to the Kabyle tribe still pierce their nipples to demonstrate both their strength and their beauty.

The colonizers, too, held perennial interest in the trend. European historians trace nipple rings back to 9th-century Roman soldiers and to the tanned torsos of pirates and God-fearing seafarers alike. Anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr traces the nipple ring back to the 14th-century court of Isabeau of Bavaria, the queen consort of France, who adorned her breasts with diamond-studded hoops, gold chains, and ringlets of pearl. The tradition was again picked up with great fervor in fin-de-siècle Paris by society women willing to bear the pain of anneaux de sein for the promise of constant, ambient foreplay: “I found that the breasts of those who wore rings were incomparably rounder and fuller developed than those who did not,” wrote a certain Madame Beaumont, who underwent the procedure as a young woman while visiting the Paris Exhibition of 1889. “[They] are not in the least uncomfortable or painful,” she writes, “on the contrary, the slight rubbing and slipping of the rings causes in me an extremely titillating feeling, and all my colleagues to whom I have spoken on this subject have confirmed my opinion.”

It was Jim Ward, named “grandaddy of the modern body piercing movement,”who brought the trend stateside in the 1970s. Namely, he introduced American piercers to the barbell, a now common style of jewelry, which he lifted from the German designer Horst Streckenbach. In 1978, Ward would open the Gauntlet, a vanguard body-piercing studio in West Hollywood.

Though public figures like Rihanna, Tommy Lee, Kendall Jenner, and the abominable former Governor of New York State Andrew Cuomo have made a lasting case for the nipple piercing simply as fashion, its histories proffer a spectrum of functions that are hardly skin deep. But commitment remains key: for those who have opted in, healing time varies — twelve weeks is normal; up to a year should be expected. Common testimony also suggests that the tender skin spoked by the metal has the tendency to grow back over it, making the object difficult, if not impossible, to remove. It is a comfort to know that there’s pleasure in permanence, though there will always be some people who will refuse, fearing the pain of the procedure. To these gentle folk, I do not recommend love.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here.

1/10