PHOTOGRAPHY BY BENJAMIN FREDRICKSON | COURTESY OF DANIEL COONEY FINE ART

Benjamin Fredrickson – Photographs – Daniel Cooney Fine Art

opens on November 7, 2019

In anticipation of Benjamin Fredrickson’s upcoming exhibition in New York, we asked him a few questions about his gorgeous subjects, his photographic process, and the evolution of categorizing nude portraiture.

Do you get to know your models before photographing them? How many of them are your friends or lovers? Some of them are friends, and some of them are people that were found through social media. I’m fascinated how social media has reshaped the way in which artists can source subjects. There are even people that “collect” artists/photographers for their online respective portfolios, collecting likes and validation. I love it. Before I.G. existed I would source people from Craigslist, Manhunt, and Adam4Adam.

In your self-portraits, your penis is erect. Is it the act of modeling, of exhibitionism, that gets you in the mood, or do you think about something or someone to turn yourself on? I’m an exhibitionist, I love showing off. I’m also a bit self-conscious when it comes to looking at myself nude without an erection. I prefer to pose in self-portraits with an erection. I love when there is someone else in the room that turns me on when I’m making self-portraits. A lot of the time, I’m by myself and thinking about someone who I’ve photographed or had an intimate encounter with. It can change with the situation. I was in Paris last summer and staying in an Airbnb and there was this frosted window in the hallway, and I just knew that I needed to make a self-portrait sitting in that window sill. There was a thrill of getting caught by a neighbor walking by. I had a camera on the tripod, it was difficult staying erect, but I made a shot that I liked.

There is a masculinity that unifies your work. How important is it for you to promote trans visibility, as in your photograph of Billy Vega? How do you approach trans men when asking them to pose for you? The first time that I photographed Billy Vega, the portrait was published in the BUTT 2012 calendar. I was thrilled when he reached out to me during his first trip back to NYC recently; it was his first time back since our initial shoot 8 years ago! He is so sexy. I crushed on him the first time that I saw him and even more so the second time we worked together. I approach everyone that I’m interested in photographing the same way, I ask if they’re interested in working with me. The masculinity that I’ve always been interested in exploring and celebrating is inclusive and diverse .

Billy Vega, 2019.

Billy Vega, 2019.

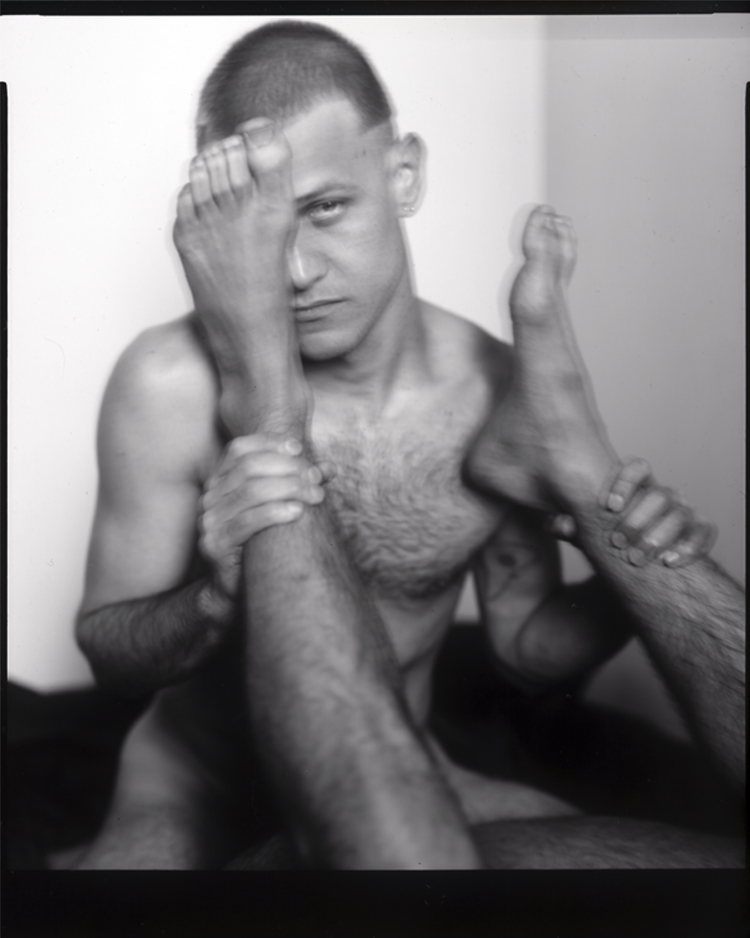

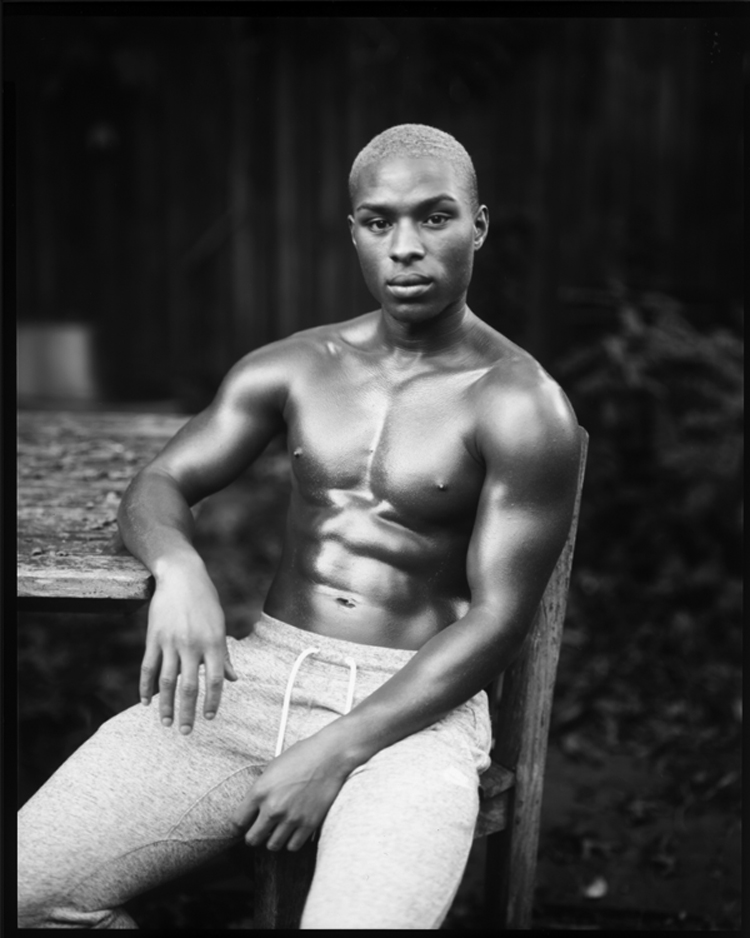

Craig, 2016.

Craig, 2016.

Nick, 2019.

Nick, 2019.

Tombstone, Milan, 2017.

Tombstone, Milan, 2017.

In your upcoming exhibition at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, one of your photographs, “Tombstone, Milan,” features a statue of a man, though the style and perspective of the photograph make it seem as though he is alive and staring at the camera. Is there a link between this photo and the others in the exhibition, related to the ‘statuesque’ or ‘timeless’ as a theme? I was talking to the amazing artist Robert Flynt and telling him about my first trip to Milan and he told me to check out the “queer” tombstones in the Cimiterio Monumental in Milan. This particular one really stood out to me. The posture of the man sitting along with the expression is so remarkable. I found it really beautiful and had to capture it. I went back to that tombstone a second time to make sure I got the right angle. As I was photographing, with a tripod, the security guard at the cemetery told me that I couldn’t shoot any more pictures. I’m so grateful that I got this shot. I think this portrait is a nice companion piece to my “Self Portrait” which is also included in the exhibition. In this photograph, I’m laying on the studio floor nude, sunbathing, eyes closed. It reminds me of the 19th century post mortem portraits. I had to close my eyes because the sun was so bright and the exposure was so long, almost 30 seconds!

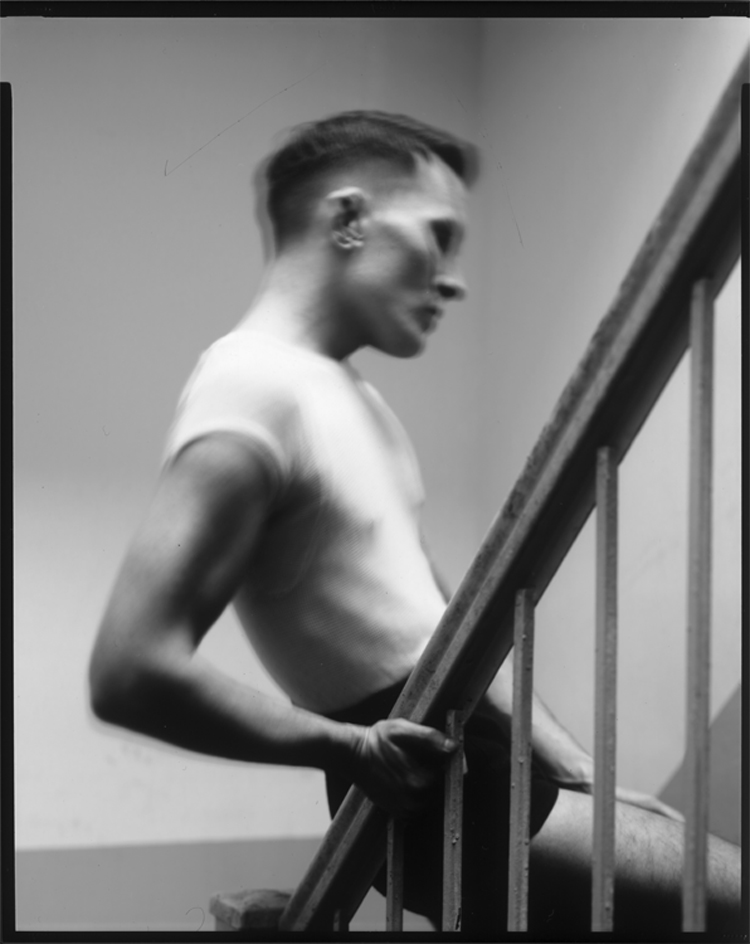

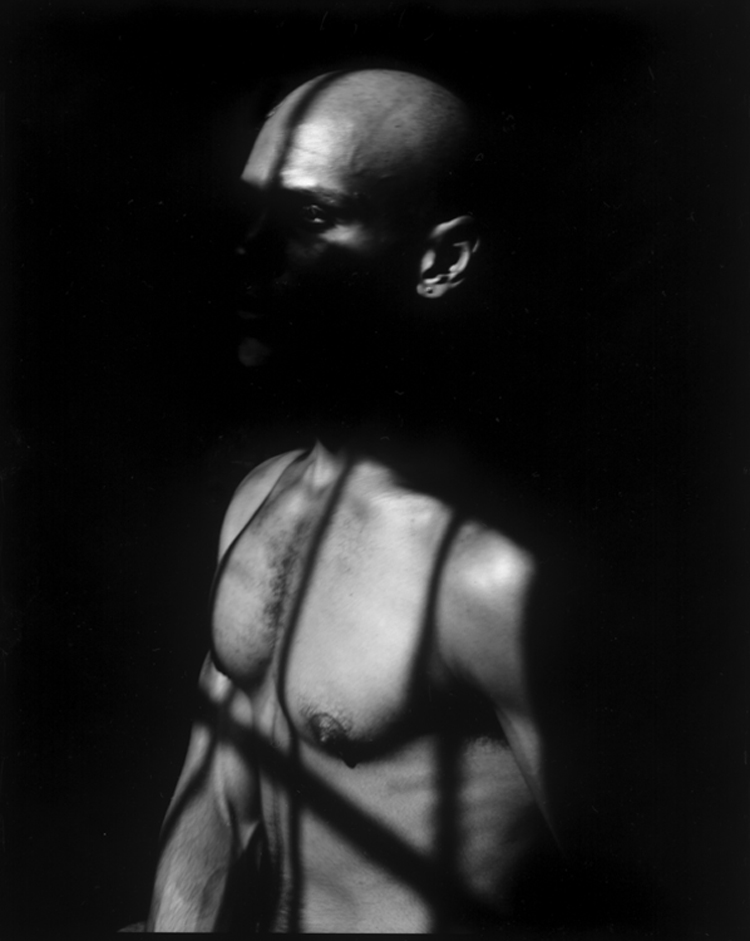

I’ve noticed many of your images capture dawn or dusk, the bedroom hours, when light pours through the windows at an angle. What time of day do you prefer to photograph your subjects? Do you prefer artificial or natural light? Many of the photographs in the exhibition were made using paper negatives, inspired by Fox Talbot’s early photographic process of the salted paper negative. This process requires a lot of sunlight and very long exposures. Some of the portraits were made with 30-second exposures. I made some in the parlor in my apartment, which has amazing sunlight, and the bars on the windows created really amazing shadows. As the project progressed, I shot in my basement with artificial light, a strobe flash. I don’t prefer natural light or artificial light; I choose based on the situation and what makes most sense for the photograph to work. The lens used was made in the 1920’s so it has a specific look. Maybe that adds to the work looking like a painting or like it’s from another era.

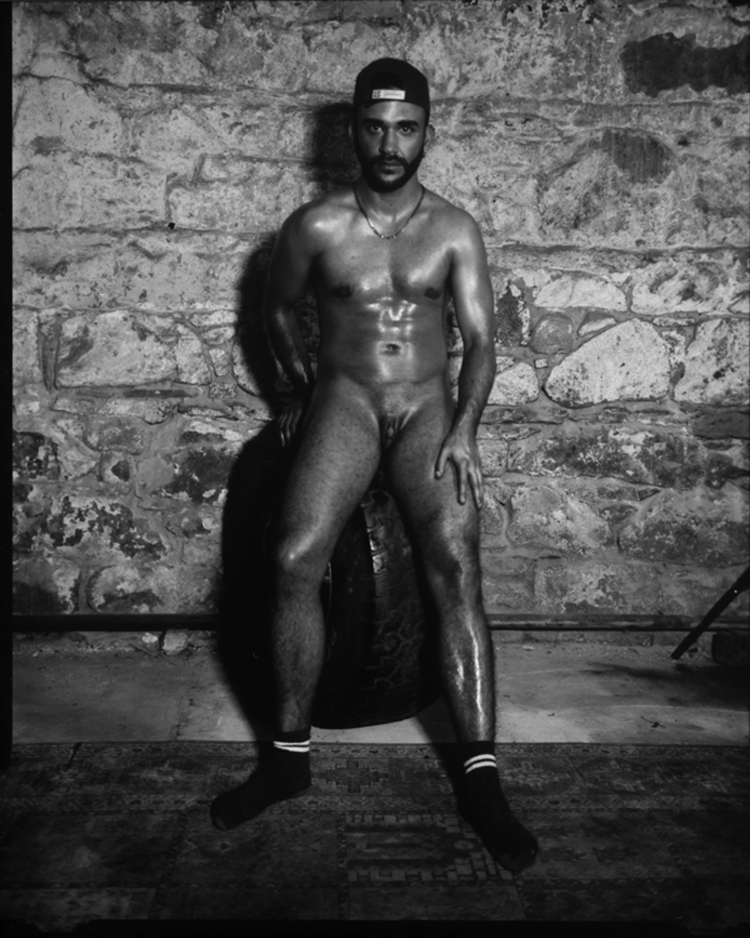

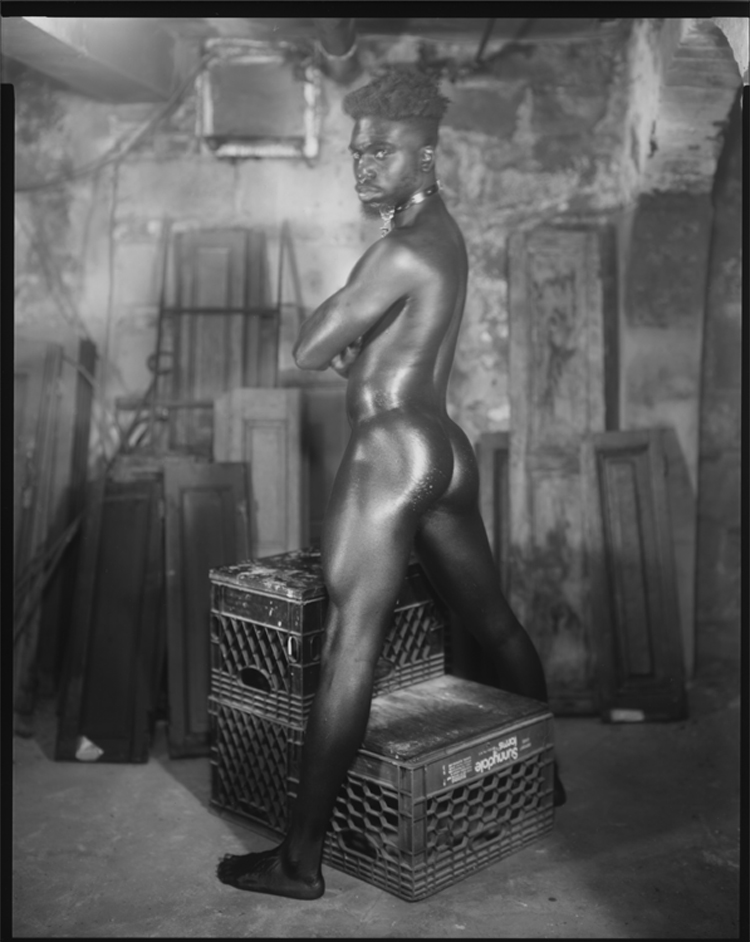

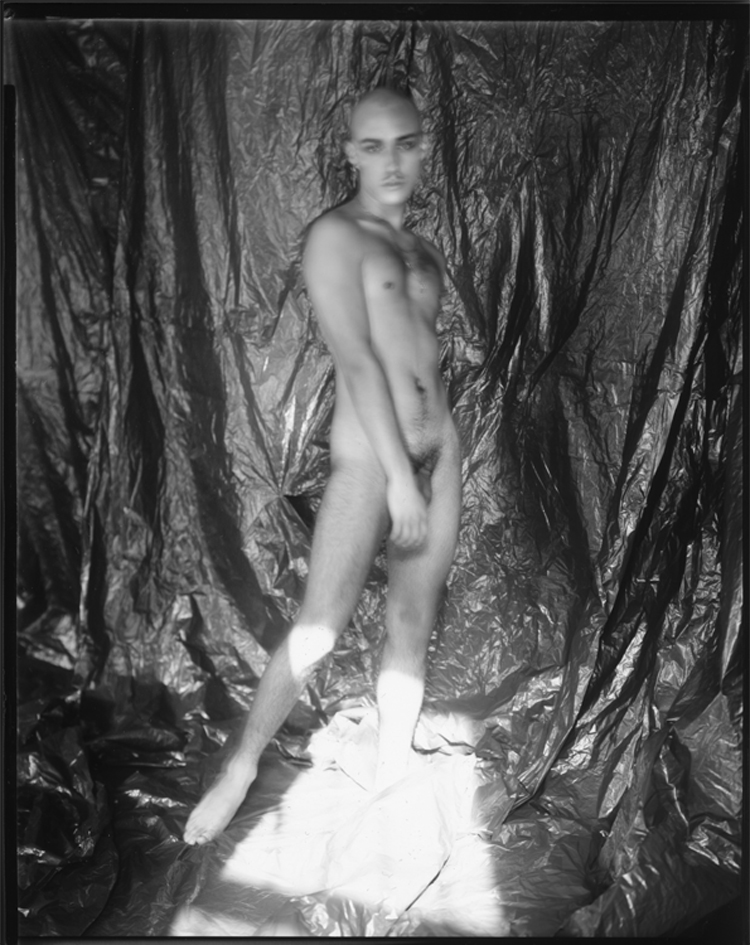

Your high contrast, black-and-white style has a link to portrait photographers of the ‘80s — the gallery essay for your opening in November at Daniel Cooney Fine Art mentions your “artistic ancestors George Platt Lynes, The Athletic Model Guild, and Robert Mapplethorpe among others.” So you think you share a common vision with any these photographers? My work is inspired by tropes found in physique photography, such as oiled bodies. I love how bodies glisten; I prefer to go overboard with the baby oil. The best part is helping to apply it on the models’ backs and hard to reach places. Bob Mizer created work in an era where he risked jail time for creating the physique photographs and distributing them. He and other physique photographers paved the way for future generations of queer artists and photographers. I appreciate the sophistication and attention to detail found in George Platt Lynes work: the lighting, use of props and posing. He was initially celebrated for his fashion and portraiture. The male nudes were uncovered later. The first photograph by Mapplethorpe that stuck with me was titled Mark Stevens (Mr. 10 1/2) and I discovered it in college. I liked that he put a man’s cock on a pedestal and photographed it. Brilliant! I think the best thing he could’ve done was to photograph the explicit and produce it with the same care that he did with his other works. He put it out there in the world to create a conversation. It wasn’t hidden away.

Your work is sensual, evoking a calm seduction, contemplatively relaxed rather than mindlessly sex-crazed. How, if at all, do you draw the lines between pornography and portraiture? How do you think this perception has changed over the decades? With this project, I wanted to explore intimacy and discover what it meant for me. In the past I thought sex and intimacy were the same thing. I created mindlessly sex-crazed work and got it out of my system. The creation of this recent body of work showed me that intimacy is sharing my creative process with others, photographing another person and being photographed by myself. It’s not about a sexual encounter being documented. I don’t think that there needs to be a hierarchy between art and pornography, but there is. I see peoples’ perceptions towards art and pornography changing, but there is still a long way to go. We are living in a world where queer and sex-positive voices are being censored and silenced, and it’s a scary thing. In these current times of adversity the most important thing is that people use their visual language to create work that sparks conversation.

Derek, 2016.

Derek, 2016.

Kai, 2018.

Kai, 2018.

Marcelo (standing), 2017.

Marcelo (standing), 2017.

Trevor, 2017.

Trevor, 2017.

Self Portrait (sunbathing), 2017.

Self Portrait (sunbathing), 2017.

Benjamin Fredrickson’s exhibition at Daniel Cooney Fine Art runs through December 20, 2019.