Cure for crabs (2004). PHOTOGRAPHY BY BRUCE LABRUCE

Bruce LaBruce: The Death Book

He is a provocateur extraordinaire – most of his oeuvre has been banned, censored, or attacked since he emerged from the queer punk scene in the 1980s.

The Death Book continues his subversive project, with the images in the book functioning as a social mirror or projective test that mine our collective unconscious, probing the depths of what we repress and censor. Just a few days shy of the United States Presidential 2020 election, Bruce and I connected on Skype to discuss his newest book. It was a gloomy day in both Brooklyn and Toronto, a fitting backdrop for our conversation which delved into death, violence, obscenity, and the psychology of taboo.

Could you tell me about the concept for the book? Baron Books, Matthew Holroyd, contacted me. He had this concept to do a series of books on death, and ask various artists to collaborate on the concept. So mine is only the second book in the series. He let me come up with whatever idea I thought would be most interesting. And I guess I took it beyond that — literally. Like, I thought it would be a good opportunity to compile all the most severely violent and crazy imagery that I’ve made over the years. It kind of has a cumulative effect. I’ve been working in gore and splatter for quite a long time. Even before my zombie movies, I was using a lot of it in my photography and at my art openings. So when you see it all together, it’s kind of startling, but I think it’s all very consistent and it really shows how my project has always been to draw attention to how this kind of imagery is so casually promoted as capitalist fodder.

Some of them, especially the car crash images, look like they could be advertisements. That one I did as this actual fashion shoot with a stylist, but I didn’t do it for any particular magazine. I did it with friends and it was kind of an exercise, more of an art project. When she’s reaching for her product, for me, it’s a critique of the fashion world as well, where violence and sexualized violence are pretty commonly exploited. I think the great example — well sort of a parody of that, I guess — is Eyes of Laura Mars. I think every photographer has done some kind of photo shoot as an homage to that movie, especially the famous Columbus Circle scene.

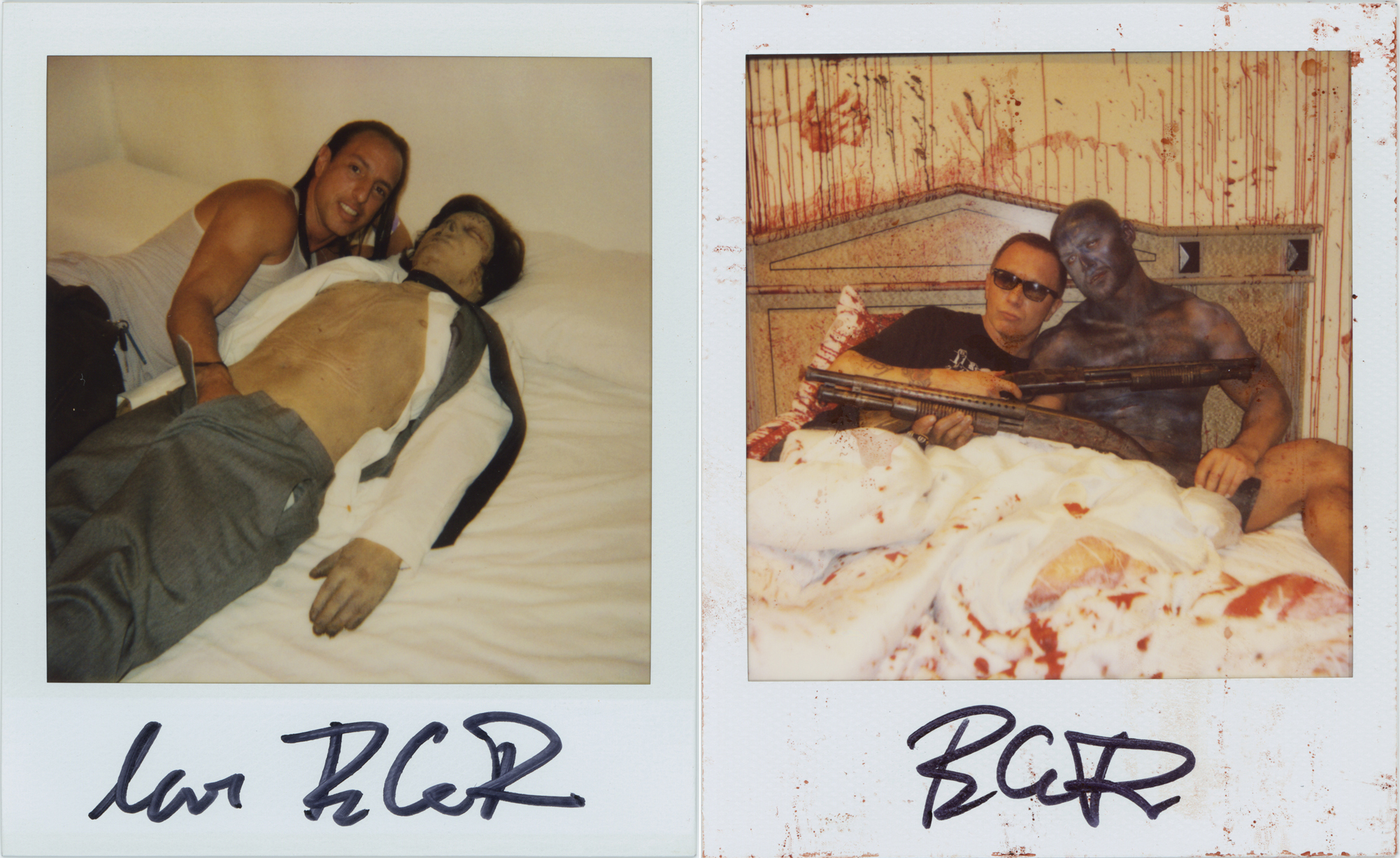

Adam Killian and Erik Rhodes, L.A. Zombie production still, Toronto (2010).

Adam Killian and Erik Rhodes, L.A. Zombie production still, Toronto (2010).

Kembra Pfahler (2000).

Kembra Pfahler (2000).

Brad Renfro with his grandmother, Toronto (2000).

Brad Renfro with his grandmother, Toronto (2000).

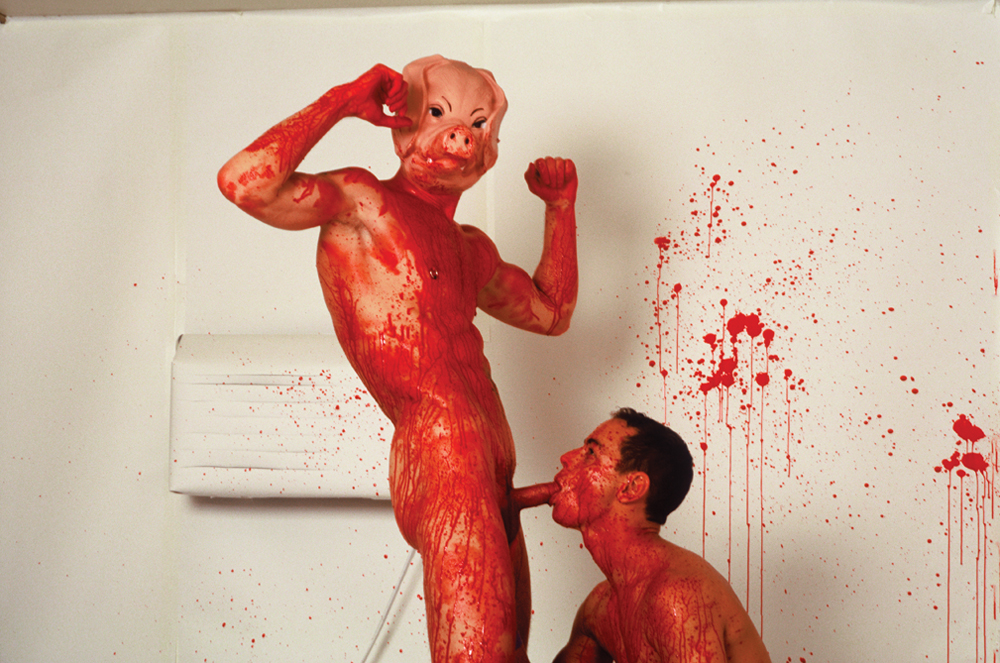

Pig’s Mask Blow-Job (2001).

Pig’s Mask Blow-Job (2001).

Nunsploitation, Model: Sasha (2002).

Nunsploitation, Model: Sasha (2002).

There also is some religious imagery in the book as well, which I thought was interesting, like the nuns. Yeah, the nuns, those images almost seem out of place in the book on a certain level because they’re not specifically violent, but the book is more about extremes and how I tend to challenge taboo and do so in terms of fetish. The other obsession I’ve had besides gore and splatter and which I started exploring quite a long time ago is the strange intersection between religious and sexual ecstasy. In 2012, I had a big exhibit at La Fresh Gallery in Madrid, which was based on that theme, and it was hugely controversial. The mayor tried to close down the exhibit, and there were Christian protestors outside every day. And, somebody threw an explosive device through the front window of the gallery the day after the opening. It didn’t go off, but it was front page news all over Spain.

Yes, Spain is still such a Catholic country. Yeah, and that’s where that kind of statement makes the most impact, you know? I used a lot of pop stars, like Rossy de Palma and Alaska in the photos. So it made it even more high-profile, but I mean, really it’s about the idea that fetish is a kind of religion. My movies tend to make taboo and fetish somewhat romantic, looking at it in a way that is almost more akin to a religious experience, with a spiritual dimension. A lot of people, when they think of fetish they think of something dirty and disgusting and kind of distasteful, but in my experience it’s more like there’s a real reverence for the object of desire, a kind of spiritual devotion.

I like to also recognize that religious devotion quite often has a sexual dimension. It’s not just like nuns kissing the feet of a statue of Jesus, but like hardcore masochism, self-abnegation and self-flagellation, which then is translated as a kind of religious point of catharsis, but it’s an obvious combination of pleasure and pain. With my new movie Saint-Narcisse, I’m also exploring that. And I was thinking of films like Ken Russell’s The Devils, of course Pasolini’s Salò, where that’s represented. It’s not meant to be so much a judgment of religion as just acknowledging how complex those kinds of feelings of religious devotion are and that they are sexual. And then also acknowledging that fetish is not just sexual, but religious as well.

I was also curious about your new film, Saint-Narcisse. Could you talk a bit about it? Yeah, it’s strange because a lot of what I’ve been doing as a photographer runs parallel to what I’ve been doing in my movies. And my last couple of films have had a religious aspect to them. The Misandrists was about a bunch of highly sexual, militant nuns, revolutionaries. It’s meant to be ironic that these lesbian separatist militants are disguising themselves as nuns. There’s also a built-in nunsploitation kind of sexualization of nuns, which is a whole sub-genre in itself. And then in my movie Gerontophilia, it was more lightly sketched in, but there’s the idea of the young boy who has a fetish for the old man as a kind of saint.

And so the new movie is about twincest — Twincest was the working title. And then I thought it was the perfect opportunity to explore narcissism as well. So it’s a loose retelling of the myth of Narcissus, and there’s a highly religious angle in it as well. One of the twins has been raised in a monastery by a demented priest who has been sexually exploiting them, and they have a very strange, highly developed sadomasochistic relationship that also has a certain emotional dimension to it. It’s a complex kind of relationship that may have something to do with the idea of the Stendhal Syndrome. Sometimes sexual exploitation is complicated because the individual actually has feelings for the person who’s exploiting them. So until they’re extracted from the situation and can see it more objectively, their emotions are quite ambivalent.

Even thinking about the gore and other shocking things in your films, you show that they’re not one-dimensional, that there are ambivalent and complex aspects to these things that are seen as being just tawdry or fetish. And political too. I’ve always been inspired by the B movies of the seventies coming out of the U.S. in particular, and also Italy. Everyone from Cronenberg to Larry Cohen to Romero to Wes Craven to Dario Argento to Sam Raimi. B movies, because they’re kind of a throw-away genre, they’re viewed in these off-the-beaten-track grindhouse and exploitation theaters. They felt almost as if they were a kind of expression of some sexual collective unconscious or something. This had a political dimension because at the time it was films that were expressing all the turmoil that was happening with the Vietnam War and the sexual revolution kind of going off the rails, a lot of upheaval and a lot of reaction against all the sexual repression that had been built up in the fifties and early sixties.

Whenever sexuality is denied or repressed, it usually comes back in some kind of monstrous form. A lot of horror is based on homosexual panic — the kinds of feelings that come from bisexual or homosexual impulses people project as monstrous.

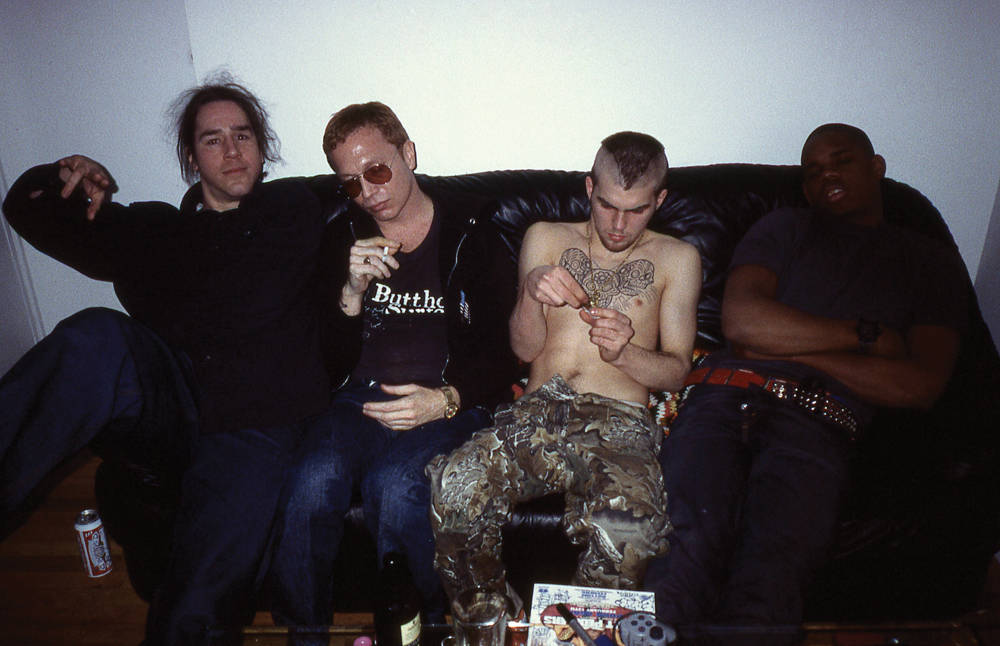

From left: Rick Owens, Bruce LaBruce and François Sagat (2001).

From left: Rick Owens, Bruce LaBruce and François Sagat (2001).

Headless Amputee (1999).

Headless Amputee (1999).

Amputee with Gas Mask (1999).

Amputee with Gas Mask (1999).

Hustler White, production still (1995).

Hustler White, production still (1995).

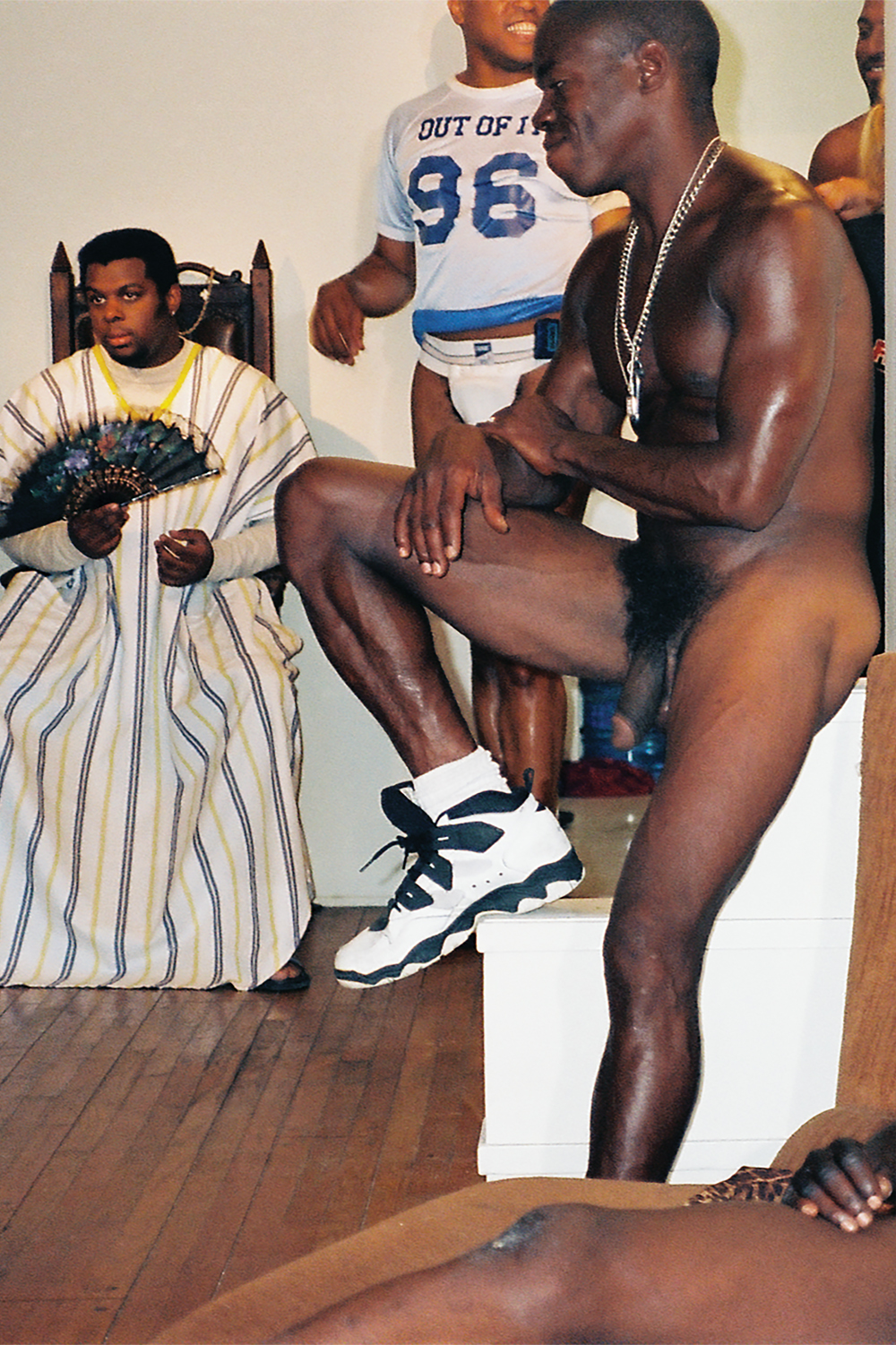

Bruce LaBruce with Semen, Dash and Kunle. (2000).

Bruce LaBruce with Semen, Dash and Kunle. (2000).

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 13, get a copy here.