All images Courtesy of the artist and 1969 Gallery.

Burn Across the Breeze

New paintings from the figurative talent Anthony Cudahy

When New York City first went into lockdown, Cudahy was unable to access his studio where large-scale works were in progress, but 2020 was still a prolific year for him, creatively speaking. Stuck at home, the painter turned inward, focusing on his late uncle Kenny Gardner’s photography archive (brilliantly curated) as well as his own stockpile of imagery that inspired several new drawings and paintings for his show Burn Across the Breeze at 1969 Gallery, on view through February 21st.

Anthony Cudahy is a great storyteller. Despite their otherworldly subject matter, his paintings occlude simplification. They’re rarely about one thing. Even a traditional portrait accrues context under Cudahy’s guidance. His scenes — which make use of saturated oranges, greens and purples — are often usurped from found imagery, or borrow directly from art history.

One of the show’s more quiet works was painted right after the toughest lockdown restrictions were lifted, when Cudahy could return to the studio, where he was no longer confined to small format. “Us (with Jacob’s Ladder, Apocalypse Tree, Lion)” shows two figures, Cudahy and his husband, Ian Lewandowski, embracing in an indiscernible setting that blends the natural world with something more sinister. Portrayed in breathy strokes of reds and orange, Cudahy and Lewandowksi embrace in the foreground on top of lush green grass that turns murky under the apocalypse tree. In the background, a path in harsh light leads the eye off the canvas, away from the safety of their embrace. I focused on the two figures at first glance, drawn to the delicate brushstrokes that didn’t carry too much paint. But the more time I spent with Cudahy’s work, the better it got . His real triumphs are always in the details, and his mastery of the materials helps him move his narratives forward. The brushy figurative style is only an entry point, and; he manages to fit whomever he’s painting to fit into a larger context. The figures may be flat, but the canvas is deep, full of varying temperatures that instruct the viewer while never demanding too much from the eye. I personally never tire at his shows, I discover.

“Painful Unknotting” (2020).

“Painful Unknotting” (2020).

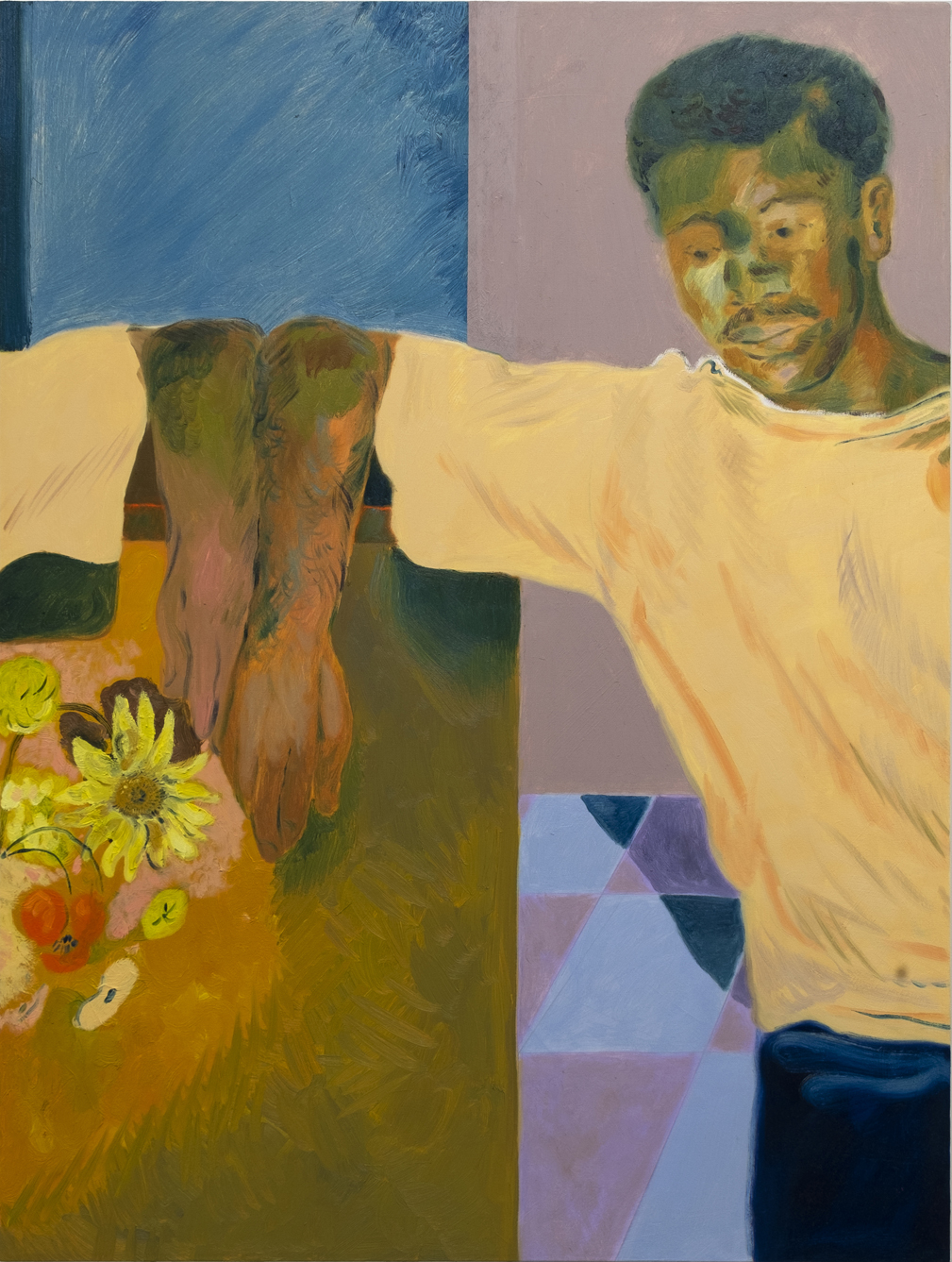

“Lean Mirrored (with Redon Flowers)” (2020).

“Lean Mirrored (with Redon Flowers)” (2020).

“Us (with Jacob’s Ladder, Apocalypse Tree, Lion)” (2020).

“Us (with Jacob’s Ladder, Apocalypse Tree, Lion)” (2020).

“Tapestry Gazers” (2020).

“Tapestry Gazers” (2020).

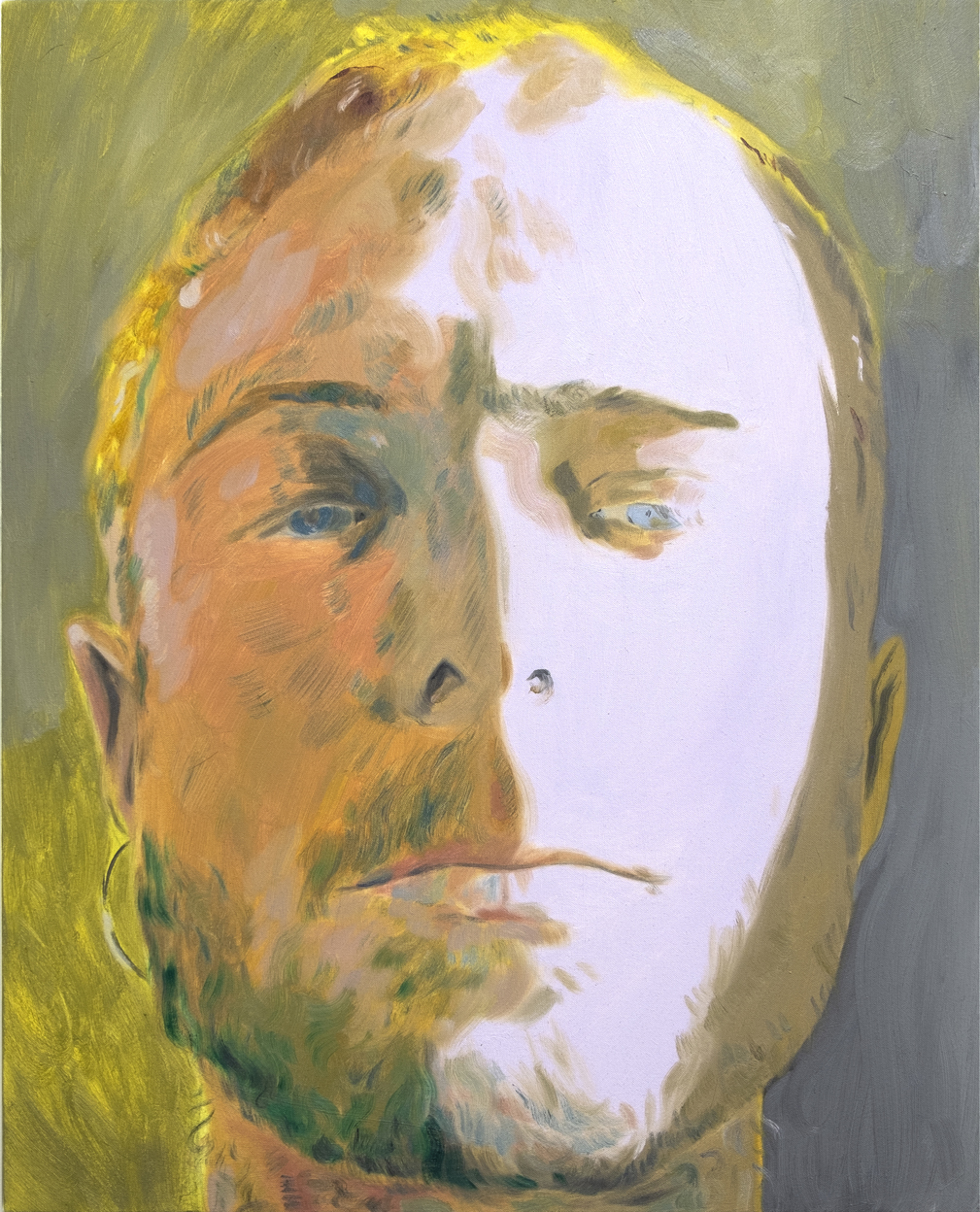

“Aurelien in purple light” (2020).

“Aurelien in purple light” (2020).

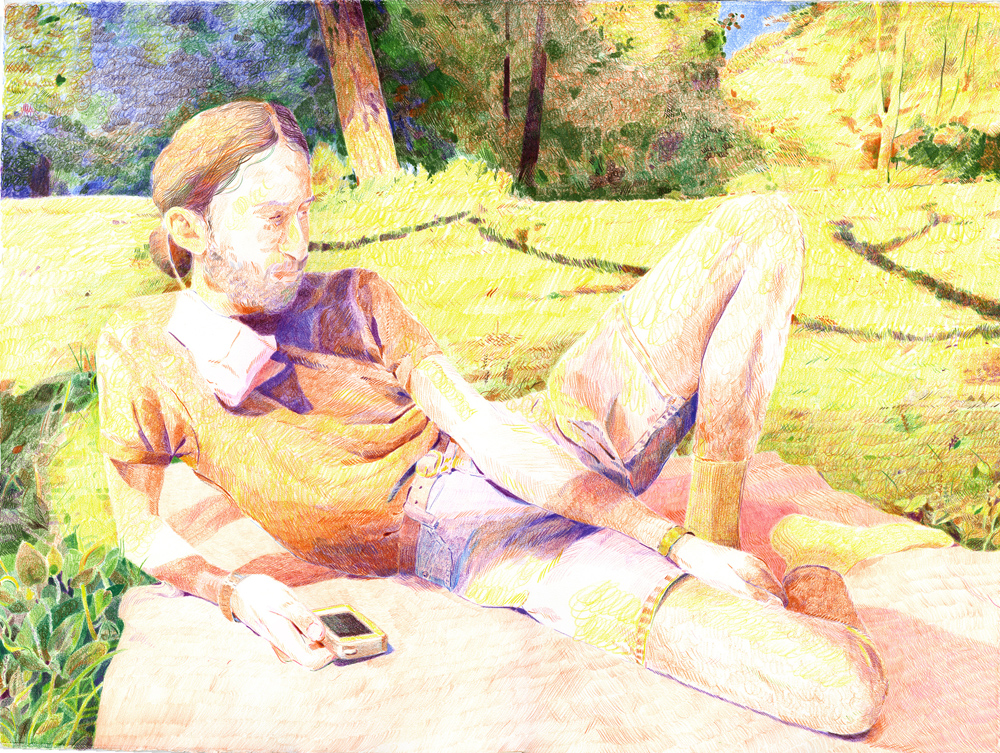

“Ian on His 30th Birthday” (2020).

“Ian on His 30th Birthday” (2020).

There is so much to discover at this show, from the beginning to end. In the middle of the gallery, “Crowd (day and night)” exhibits Cudahy’s classical painting talents. There are many figures in this busy public scene, with those in the foreground sharing a warm tonality, while in the top right of the canvas, distance is painted into the scene by a fabulous use of light. It is a canvas reminiscent of the Medieval period, with fluctuating scales and flat figures showing the breadth of a group, but it also feels like a photograph to me. A smartphone is present, but we don’t see what’s on the screen. Some faces are visible, others are turned away. When Cudahy paints, such disparate mediums share a common thread. Texture helps him prioritize moments over total context. By giving us just enough context, Cudahy allows the viewer to construct their own narratives. This is what makes Cudahy a great storyteller. One can discover whatever’s needed in his work. I am sure it is there in some corner, or within one of his character’s expressions. His paintings always show different moments, but seen in concert, I only see a specific period of time. It’s a deeply authentic approach to the medium, and it requires great patience. I like to think the paintings discussed their own hopes and desires with Cudahy during production. What they show and what they hide is their decision, too. The painter is just the practitioner who, luckily, in this case does not genuflect to the market, nor does he make himself available to commercial trends. His work exists wholly inside of itself, and he is in service to showing that world.

On a recent Instagram live, Cudahy guided viewers through the show, sharing some inspiration behind the new works. When Cudahy came to “Painful Unknotting,” a canvas portraying a girl at work untying a knotted rope, he stopped himself from explaining what that painting meant. He said he would rather know what the painting meant to other people, which seemed to indirectly ask, How do we look at art in times of crisis? It’s best not to pathologize, but grief is best treated with understanding. For Cudahy, his husband’s medical history played a crucial role in his pandemic response, and as a result, Lewandowski holds the thematic center of the show, and Burn Across the Breeze is antithetical to the kind of pandemic painting quickly hung around Chelsea last Fall. Those works relinquished some artists from what they were doing in favor of what they could be doing. Cudahy is more pragmatic at the canvas. His new paintings pick up where his work left off. The pandemic is present, but it does not carry too much emphasis. For many Americans, the pandemic persists, but it is becoming anecdotal for the middle-class. Many picked up where they left off, but what we learned gets applies now.

“Cross the Breeze” (2020).

“Cross the Breeze” (2020).

“Red knot” (2020).

“Red knot” (2020).

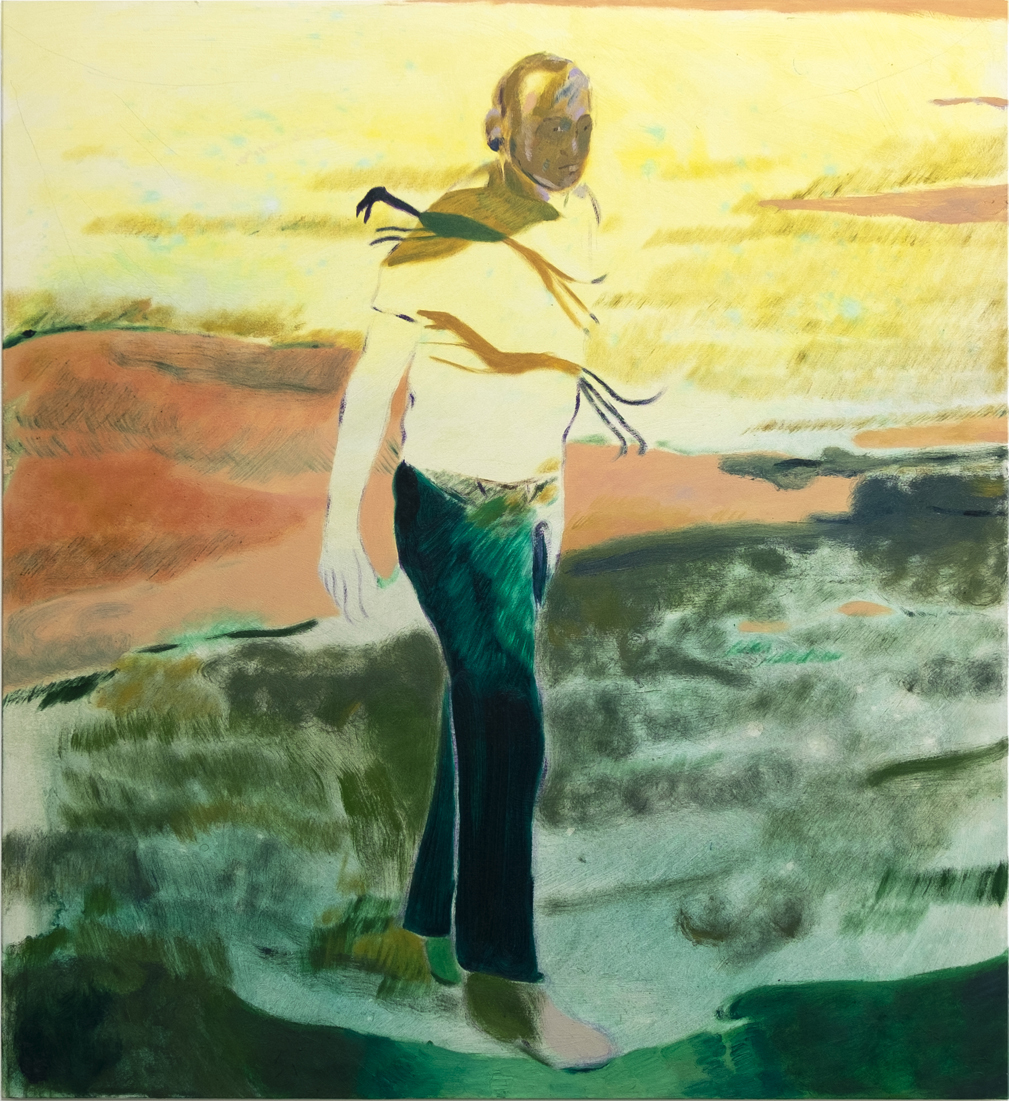

“Ian on the border ii” (2020).

“Ian on the border ii” (2020).

“Under and behind (Narcissus on the table, mutant flower outside)” (2020).

“Under and behind (Narcissus on the table, mutant flower outside)” (2020).

“Lion” (2020).

“Lion” (2020).

“Crowd (day and night)” (2020).

“Crowd (day and night)” (2020).

Burn Across the Breeze, Anthony Cudahy, 1969 Gallery (103 Allen St.) through Feb. 21st 2021.