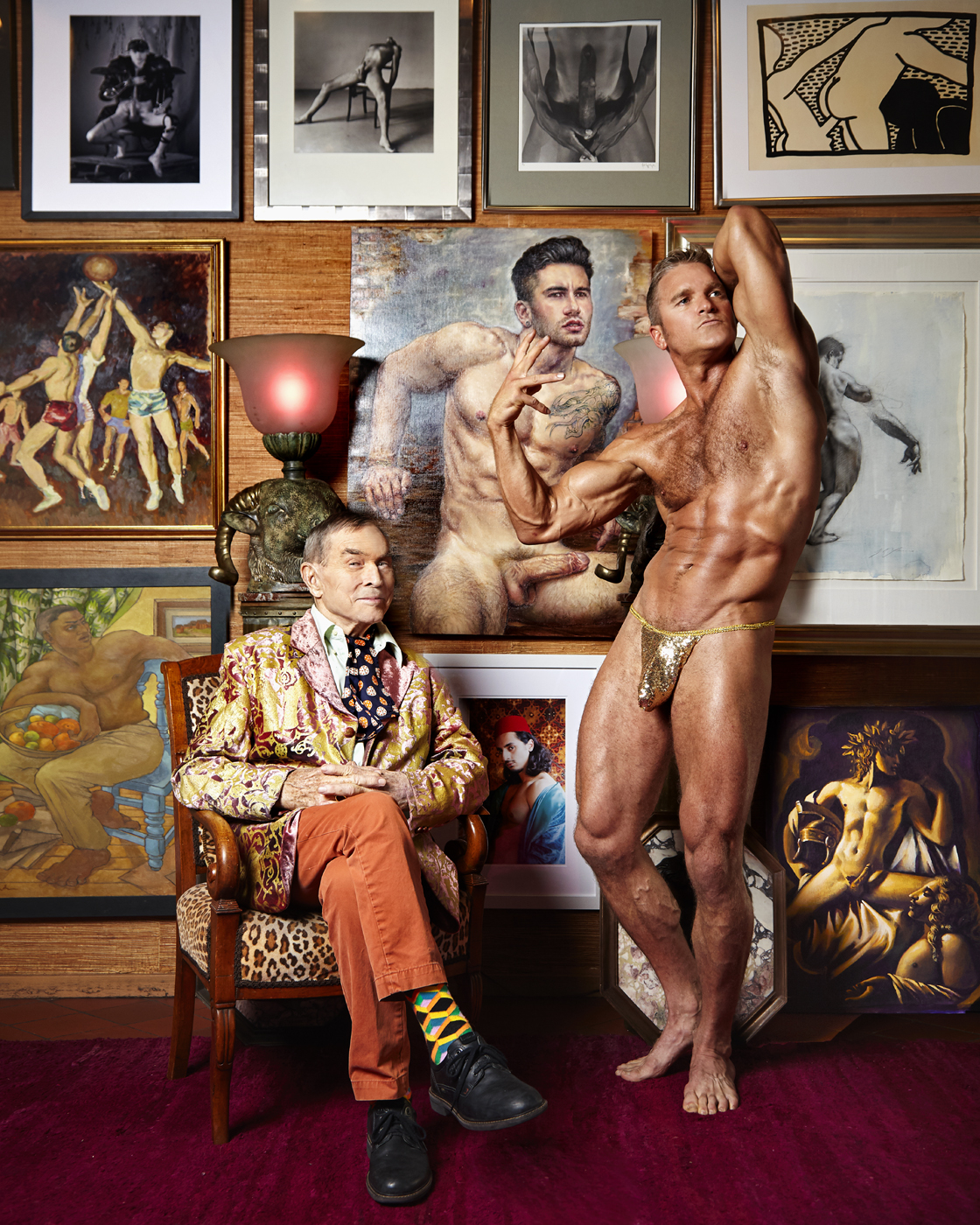

Photography by Steven Menendez | This image currently hangs on one of the walls of the Phallus Palace.

Charles Leslie

Charles Leslie is the renowned co-founder and owner of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in New York. We visited Charles in his iconic SoHo loft, often referred to as The Phallus Palace for its rich penile motifs. Surrounded by a small army of phalli, our conversation touched upon his acting career, his love life, the city’s gentrification, and Frank Sinatra’s dick.

Where did the name “The Phallus Palace” originate? It was a girlfriend who said, “I’m going to dub your place ‘The Penis Palace.’ ” I told that to another girlfriend, and she said, “Oh, Charles, that’s so crude. It needs a classier name — I’m going to call it ‘The Phallus Palace.’ ” And that stuck.

What was her name? Rita Kallerhoff, who is an artist. She lives in Morocco — she’s 72, living with her beautiful 39-year-old Moroccan lover. When she first came to New York, she didn’t know how to speak English. She was put in the hands of a woman who said, “Now darling, first I’m going to dress you properly. Then you’ll smoke a cigarette, read a magazine, and sit in the lobby of the Plaza Hotel. Sooner or later, someone will speak to you briefly and leave a room key in your hand. When you have that room key, you go to that room” — where she found some jerk waiting to fuck. She was told to accommodate him, which she did. Overnight, she became a very high-class call girl. Two of her clients were Frank Sinatra and Burt Lancaster. At the end, Rita said to me, “Sinatra was a lousy, uncaring lover. Burt was a perfect gentleman.” It wasn’t about endowment; it was the manner in which they did the deed. Wasn’t it Ava Gardner who said “Frank weighs 120 pounds, 20 pounds of which is his body, and 100 pounds of which is his cock.”

When did you discover your interest in queer art? When I was 7. I didn’t perceive it as queer art, but my father invested in a beautiful set of the Encyclopedia Britannica. As fate would have it, the first volume I picked up opened to Greco-Roman sculpture. With that, I was on the road.

Which historical era had the sexiest guys? There were moments in the Roman empire that had really sexual people, like Marcus Antonius, Hadrian and his boy Antinous. A lot of Romans had very tricky sex lives.

Do you look for the same things in romantic interests as you do in the guys portrayed in your collection? Not precisely. We don’t happen to life, it happens to us. The men I’ve been involved with have always just appeared magically, and I’ve never been looking for them. They appear and lightning strikes. They don’t have to be Hollywood beautiful, but they can’t look like trolls either. It’s the whole ensemble that works; if they’ve got a sense of humor, if they’ve got reasonably nice looks, and if they’ve got basic intelligence.

Of all the men you’ve known throughout your life, who has intrigued you the most? I suppose it was actually Fritz [Lohman], my partner of 48 years. When I first met him he was in such an odd world. He was a renowned interior designer and decorator; he had an international clientele. He was caught between New York gay life and incredibly high-end socialites. I found it a very odd position to be in, but he handled it gorgeously. Some people wouldn’t be able to elide those two things, but boy he did.

How did you two navigate the tension between those worlds? We navigated that in the same way I navigated eating an artichoke. When I was 17, in school in California, I had a lover who was 10 years older than I. I was suddenly swept into a world of relative sophistication. One time, at a dinner party, they served artichokes. I didn’t know what the fuck it was; I thought it was a cactus or something. So I carefully chatted with the lady next to me while watching other people begin to eat their artichokes, and simply copied them. That’s been my rule of thumb ever since, though now I don’t need it. Still, I never had to do it twice.

When you met Fritz, what was your first impression of him? Well, in the beginning I could only see his cock because we were in a back room. Which was delightful, by the way.

What kept the two of you together? Mutual interest in so many things. We loved ancient history and we loved travel; wherever we went we climbed to ancient ruins and remote lost places. The other thing that kept it together was the great gay contract. After the first two years, you couldn’t separate us.

But soon thereafter, I’d notice him scoping out some other guy and he’d notice me doing the same thing. Finally he said, “Charles, it’s time for us to have the talk.” I remember almost verbatim what he said. Of course, I was already thinking this way. I just didn’t dare mention it because I thought it would ruin our relationship. He said, “Charles, men can be hardwired for emotional fidelity, spiritual fidelity, social fidelity, but they cannot be hardwired for physical fidelity. So, the way we’re going to protect our relationship is to open it up.” And we did. Because of that, we lasted for 48 years, until he died.

How did you two come to live in the Phallus Palace? I was the one who dragged him down to SoHo; I wanted an editing studio because I was working in film at the time. When I saw an ad for 1,800 square feet of space for $3,000, I just bought it. Finally I said, “Fritz, I have to tell you, I’ve done something.” He said, “What now?” You wouldn’t believe how grotesque this place was. It was filled with rat shit, cat shit, bat shit; it was filthy. All these buildings down here were semi-abandoned. A lot of them were converted to sweatshops. This floor was where they made Dynell wigs for dolls. Women were hired to work 10 hours a day for $2 an hour. As it turns out, Dynell was poisonous.

How long did it take to make the space livable? The length of a pregnancy. From the moment we started work to the moment we were able to invite people in for cocktails, it took 9 months, almost to the day. It was fast, Fritz had all the connections; he knew who to call to do what. You wouldn’t believe the state of this place. We had to wear raincoats and masks and goggles and shower caps, it was just shocking. But the result was OK.

Did you start your collection when you first had the apartment? I started my collection in Germany with the U.S. Army, when I was 20. I found a little shop in Heidelberg. The shopkeeper looked at me and boy, did he figure me out fast. He said, “Boy, I have some things you might like to see in the back.” He pulled out a flat file, and there were some beautiful drawings of male nudes from the ’20s or ’30s. I bought two and sent them back to New York for a friend to take care of until I got back. I stayed in Europe after I got out of the Army, so I didn’t get back for 10 years.

What’s your favorite piece in your home? The double nude behind you, because it has in it the great love of my life, Fritz Lohman. Of course, there I am on the bottom, as usual. I should mention, it’s by a great artist who is now gone, Marion Pinto. She was a great star in the SoHo scene back in the ’60s and ’70s.

Was the idea for this painting the product of a friendship between you and Marion? Well, Marion was a serious feminist. She was very bisexual, ambidextrous, she had boyfriends, girlfriends, rats, cats, bats, you name it. She wanted to objectify men. So she said, I’m going to put on a show called Man as a Sex Object. She got all her male friends in SoHo — straight, gay and everything in between — to pose for her. The show was a smash hit. She then approached Fritz and myself and said, “Well, since you two are a pair, I’m going to do you together.” We posed for her and that was the result.

Charles Leslie photographed by Steven Menendez at home in SoHo, New York, July 2019. The male model in the image is the legendary penis painter Brent Ray Fraser.

Charles Leslie photographed by Steven Menendez at home in SoHo, New York, July 2019. The male model in the image is the legendary penis painter Brent Ray Fraser.

What makes a work of art compelling to you? I suppose primarily it has to be magisterially executed. If it’s sloppy, if it’s clear the person doesn’t know how to draw, or if it’s remotely abstract, I’m totally uninterested.

Do you think your time in Europe informed the figurative styles that you sought out in your collection? After I got out of the Army, I stayed in Europe because I got an acting job with an American theater company. Then, on the G.I. Bill, I got myself into the Sorbonne for two years. I would say Europe in general — but particularly Paris those two years — was my Éducation sentimentale. I really grew into a fairly decent gay man as a result of that time.

Now that you’ve mentioned it, could you take us back to your acting life? It was in Europe first, then in New York. When I got out of the Army, I was picked up by an American company in Europe. They sent a message out to the universities: “Open auditions for a touring theater company.” I thought, Why not? They were in Paris during my last term at the Sorbonne, so I went, auditioned and got the job. We toured for 14 months, during which I nearly fucked my brains out. When you’re touring with a theater company, there are all these stage door Johnnies… I mean, you didn’t have to hunt for a date, they were there at the door.

How did you become an actor? Well, I was trained in the theater. When I was a boy in Deadwood, South Dakota, I was extremely interested in the theater. We didn’t have theater, but I knew what it was. When I was 15, I subscribed to a magazine called Theatre Arts. I and another boy, who was also gay, would read through plays together. By the time I was 17, I knew I wanted to study formally. I left South Dakota the day after I graduated from high school and got myself to Los Angeles. By the time I got there I had no money left, but I discovered that there were any number of older men who were willing to help a greenhorn from South Dakota. I met them all in the bus station.

Were you out at the theater? Out? I’ve never been in. Anyway, I had a great time in the theater, but I wasn’t destined to be an actor all my life. I got interested in other things.

Why did you feel it was important to create a space for queer work in the arts market? Because, by that time, Fritz and I knew so many good artists who couldn’t show their work.

Some of them had good galleries, but they couldn’t show some of their best stuff because it was just forbidden, verboten, obscene. We thought it was bullshit. So we contacted several gay artists we knew in the neighborhood, and we said we’re having a show of homoerotic art. It was surprising what came out of the woodwork — a lot of them had stuff they hadn’t shown to anybody except friends. I still have some of that original stuff — a Pavel Tchelitchew from 1930, for example. We have wonderful work from Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, etc. That show was the seedling for what has become the museum. It took us a long time to get the mainstream establishment to take us seriously, but now they do, after about 50 years. But there were moments when we didn’t think we’d survive as an institution, because we got no help. I expected rich gay men to come out of the woodwork to help us — but not on your life. Especially if they worked in the mainstream art establishment. They were too busy covering their asses.

In the arts market, mainstream pieces are sometimes treated more like commodities than works of art. Do you think queer artists have similar relationships with collectors and consumers? I’m afraid they do, more and more. It’s happening. But, on the other hand, openly queer art is still marginalized, although we now have superstars like Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, and David Hockney. But there’s still a kind of scrim between the absolute acceptability of most serious art and art that is patently gay.

You began your gallery work around the time of the Stonewall riots in 1969. What was your experience that night? Amazingly, Fritz and I were at home that night. Usually we were out at a disco. We were disco babies; Fritz was a great dancer and so was I. We must have been exhausted, playing with too many boys. At two in the morning we got a call from a friend in the Village who said, “You’ve got to come to Sheridan Square right away.” I said, “It’s two in the morning, what’s wrong?” I heard all this yelling and screaming in the background, and he said, “We need everyone here, come now.” He hung up. The Village is right here, so we got dressed and walked up. It looked like the end-of-the-world riot — hundreds of people storming around screaming at the police. I tell you, from then on, things started to change. The City Council got involved because nobody had ever seen gay people rise up angrily. The Daily News had a funny headline: “Queen Bees Stinging Mad.”

I understand you and your partner Fritz Lohman partially supported the gallery, foundation and museum through earnings from SoHo real estate purchases made in the late ’60s. Yes, when we were young SoHo pioneers, I dragged Fritz down from his elegant duplex on East 58th Street to the bowels of SoHo. He quickly fell in love with the neighborhood. We used our resources to underwrite the foundation until we finally started getting some help from outside. It took a while. Now that we don’t need it, we get lots of help from the government, from the Commission of Fine Arts, and on and on. It’s how life works.

What was your experience as a witness of SoHo’s gentrification? Well, in the beginning, SoHo was loaded with artists and art-related enterprises. Eventually, we had a meeting with doctor Chester Rapkin, who was a famous urbanologist from Princeton University. We were trying to get the zoning changed to make all this legal, because we were technically living here illegally. The city considered all these spaces unfit for human habitation.

Unfit! So we were fighting tooth and nail to get a zoning change. Chester said something, sitting literally where you are right now. He said, “I want you people to understand that if you achieve this, your neighborhood will not stay the same for even a moment. After the zoning is changed — because I think you can succeed in changing the zoning — it will not stay the same. It will be like a tiger by the tail and will go in a direction that you may not intend.” We thought we could keep it exactly as it was. Yeah, right.

Sure enough, once the zoning was changed, little boutiques started to pop up. People who had no connection to the arts whatsoever started appearing in 3,600-square-foot lofts. I walked down Wooster Street one day in 1972 and there was a charming little convertible roadster sitting in front of the building. Out popped a young man and a young woman in tennis outfits. I thought, Well, there goes the neighborhood. And it went — it became totally, suddenly trendy and chic and chichi, and so on. But I ain’t going nowhere. I’m staying.

What was the most challenging part of running the gallery, foundation and museum over the years? Well, we tried to run it on a profit-making basis, which proved to be hilariously impossible. We underwrote it for a long time until our accountant said, “Listen, boys, you’ve got to turn this thing into a nonprofit foundation; otherwise you’re going to go broke. I’m not going to let that happen.” So we turned it into a nonprofit foundation.

We had a great lawyer, a beautiful, big, voluptuous lesbian named Erica Bell. At the time, she had trouble talking the federal government into issuing an approval for us as a nonprofit organization because we were called the Leslie-Lohman Gay Art Foundation. Whoever she was talking to didn’t like the word “gay.” Finally, somebody suggested we call it the Leslie-Lohman Art Foundation — drop the “gay.” Absolutely not! That missed the whole point. Eventually, they finally ran out of reasons to say no. So we became a verified nonprofit organization, and little by little we started to attract attention.

What was the most exciting part of running it? I suppose it was 10 years ago, when the Board of Regents of New York suddenly proclaimed us a Museum of the State of New York. No one warned us! I suddenly understood why we had encountered so many people coming in and out of the museum asking questions, people we didn’t know who looked like middle-class businesspeople. They said, “I’d love to learn more about your program.” Suddenly they discovered we had a film cycle, poetry readings, lectures, we had the works. Bingo, we were finally a museum. And we’re not going away now. We’re here to stay.

Would you like another glass of wine? Oh, this isn’t wine, this is cold brew. I don’t drink — not because I’m against it, because I used to drink quite normally. I just don’t have the taste for it anymore. I used to be able to belt five martinis and not blink an eye. My god, Fritz could do more than I could, which was amazing. He’d go to a martini lunch, have three martinis with lunch and go back to work. I couldn’t do that. It was very New York City — even if you hated it, you had to do it. And in the early days they were gin martinis, which are really ghastly. We later moved to something we called Blue Whales, which was crushed ice in a cup filled with vodka and a big shot of Blue Curaçao.

What’s your favorite song? I have two favorite songs. “My Buddy” and “Fools Rush In.” If you ever want to listen to a beautiful song, listen to the Mel Tormé version of “My Buddy.” I like too many songs. I’ve always been smitten by songs.

Underrated sex act? The first one, I would say, would be cuddling. The second would be rimming. It’s not underrated in my book. I love to give and receive.

Best season in New York City? All seasons. New York is good for all seasons; there’s always something going on. If you don’t know that, you’re not very smart.

If you had one night in New York, where would you go? Well, in the old days I would have gone to a bathhouse.

To see the rest of the feature get a copy of GAYLETTER Issue 11 here.