DRAWINGS BY DANIEL MARCELLUS GIVENS | PORTRAITS BY CHRISTOPHER TOMAS

DANIEL MARCELLUS GIVENS

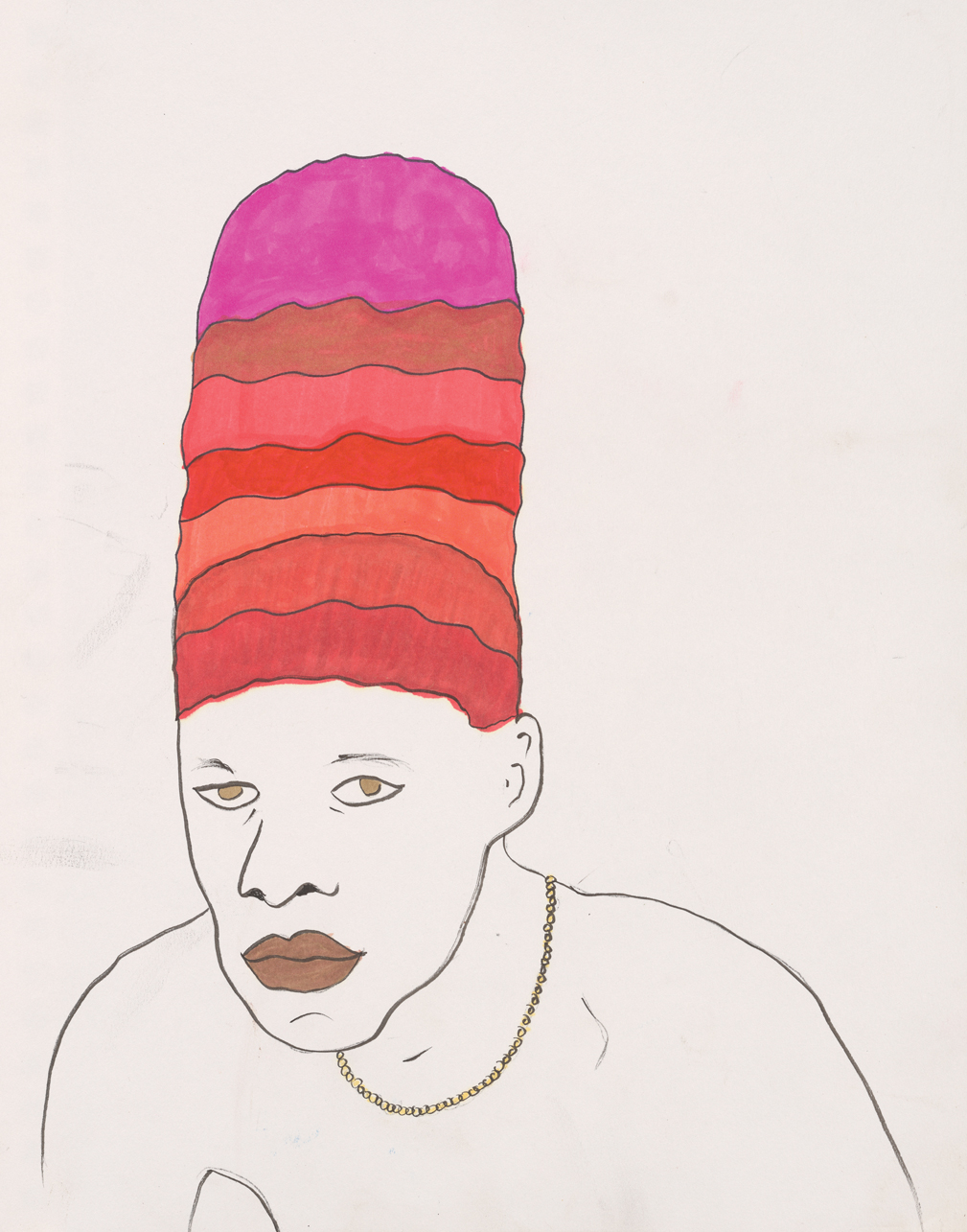

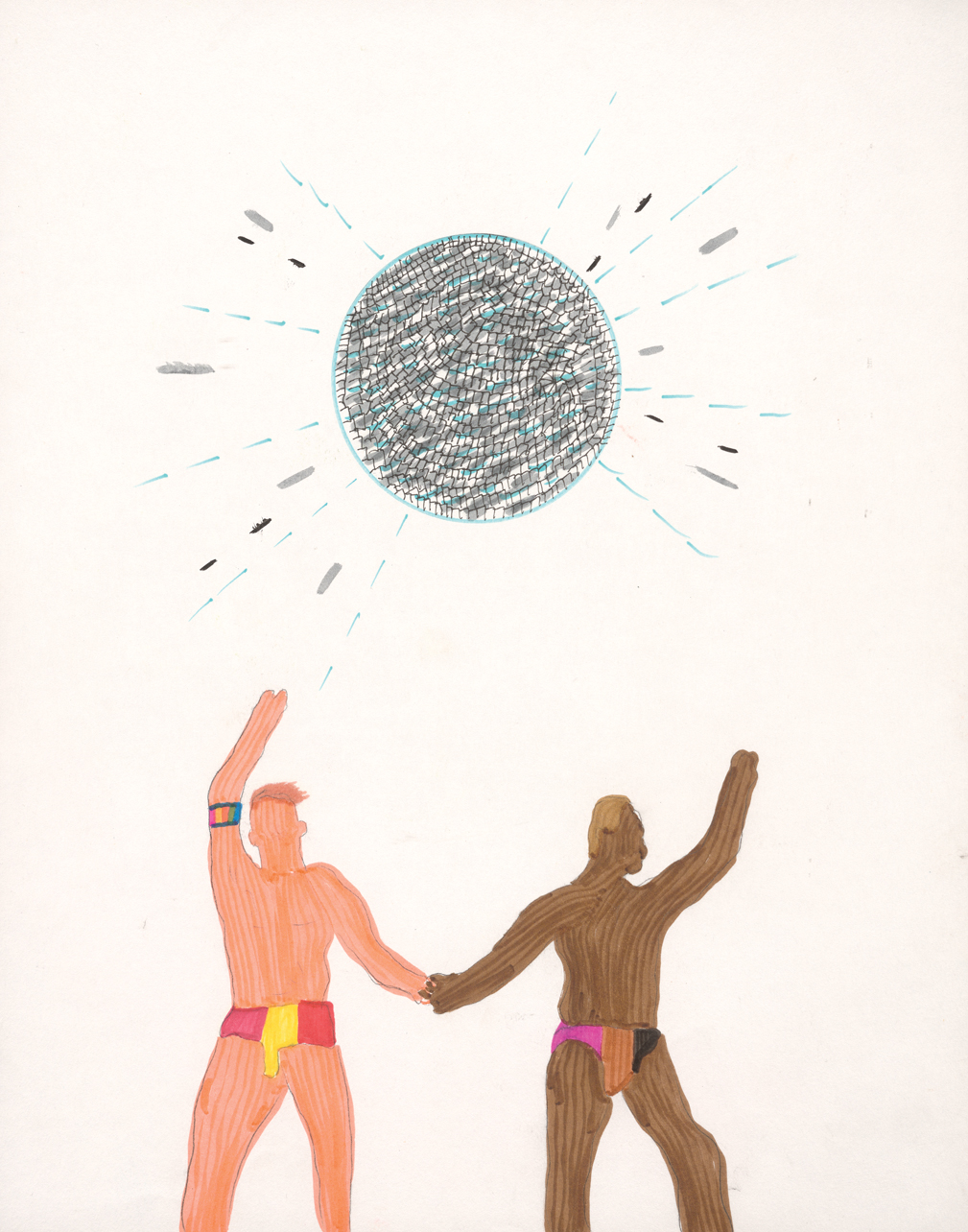

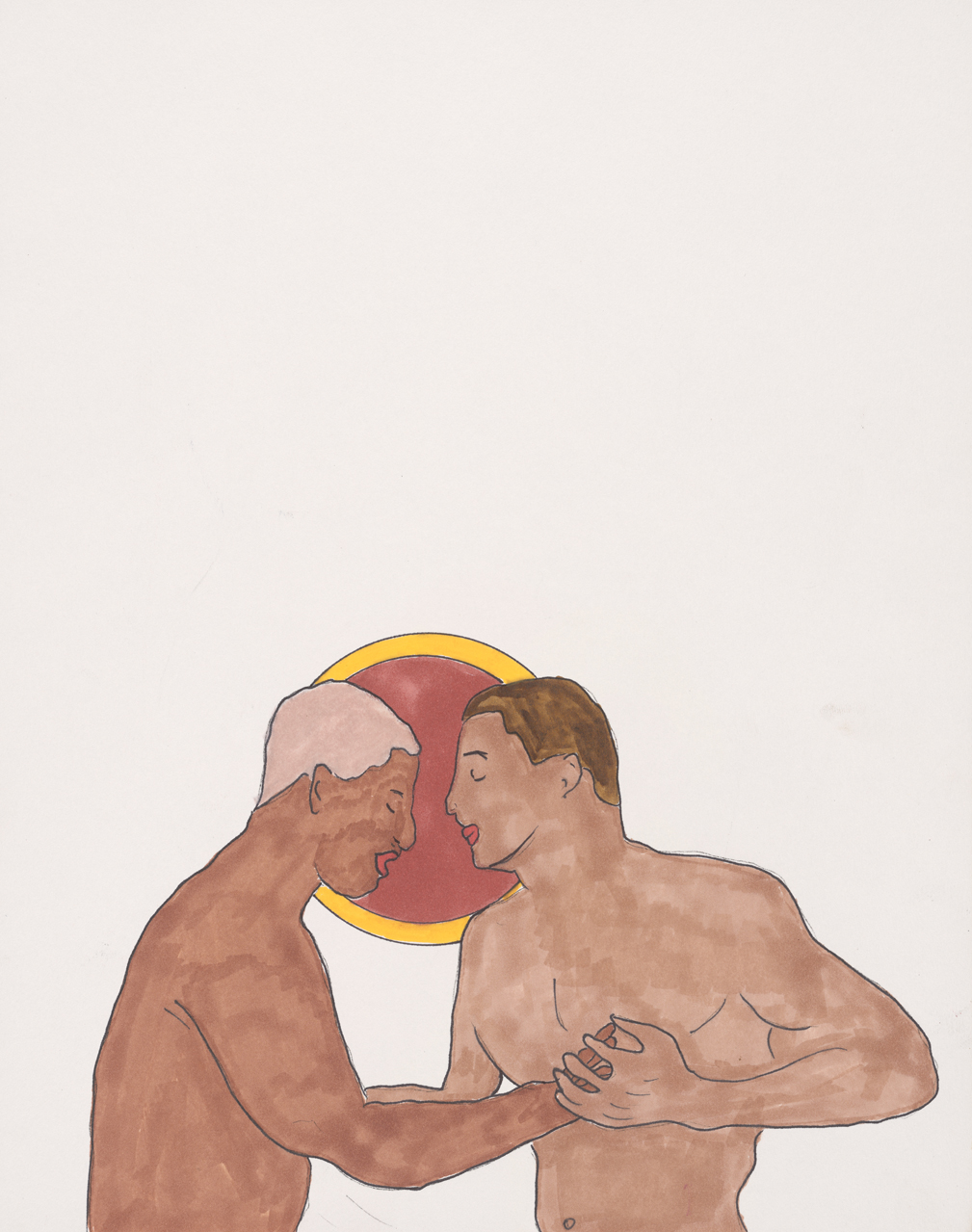

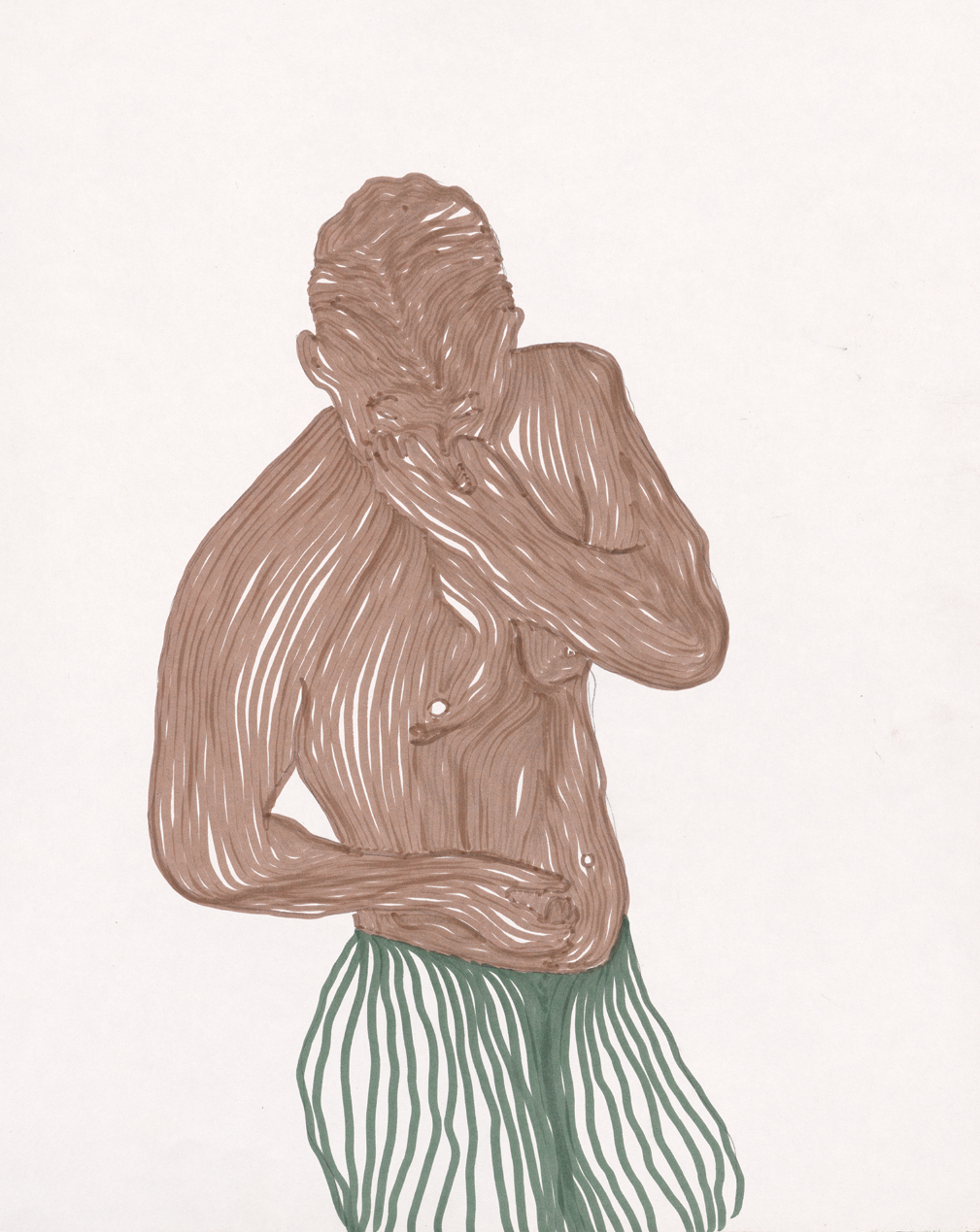

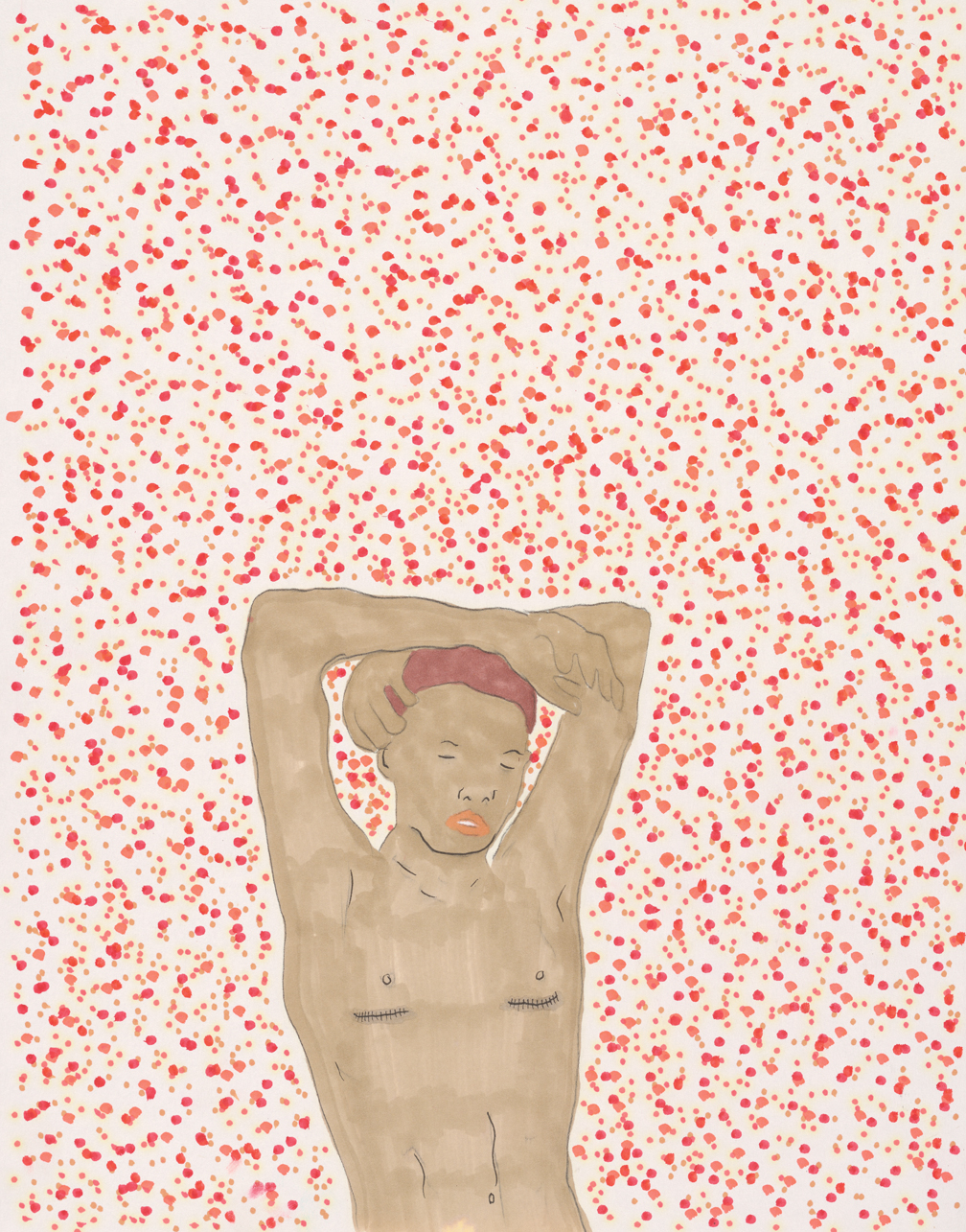

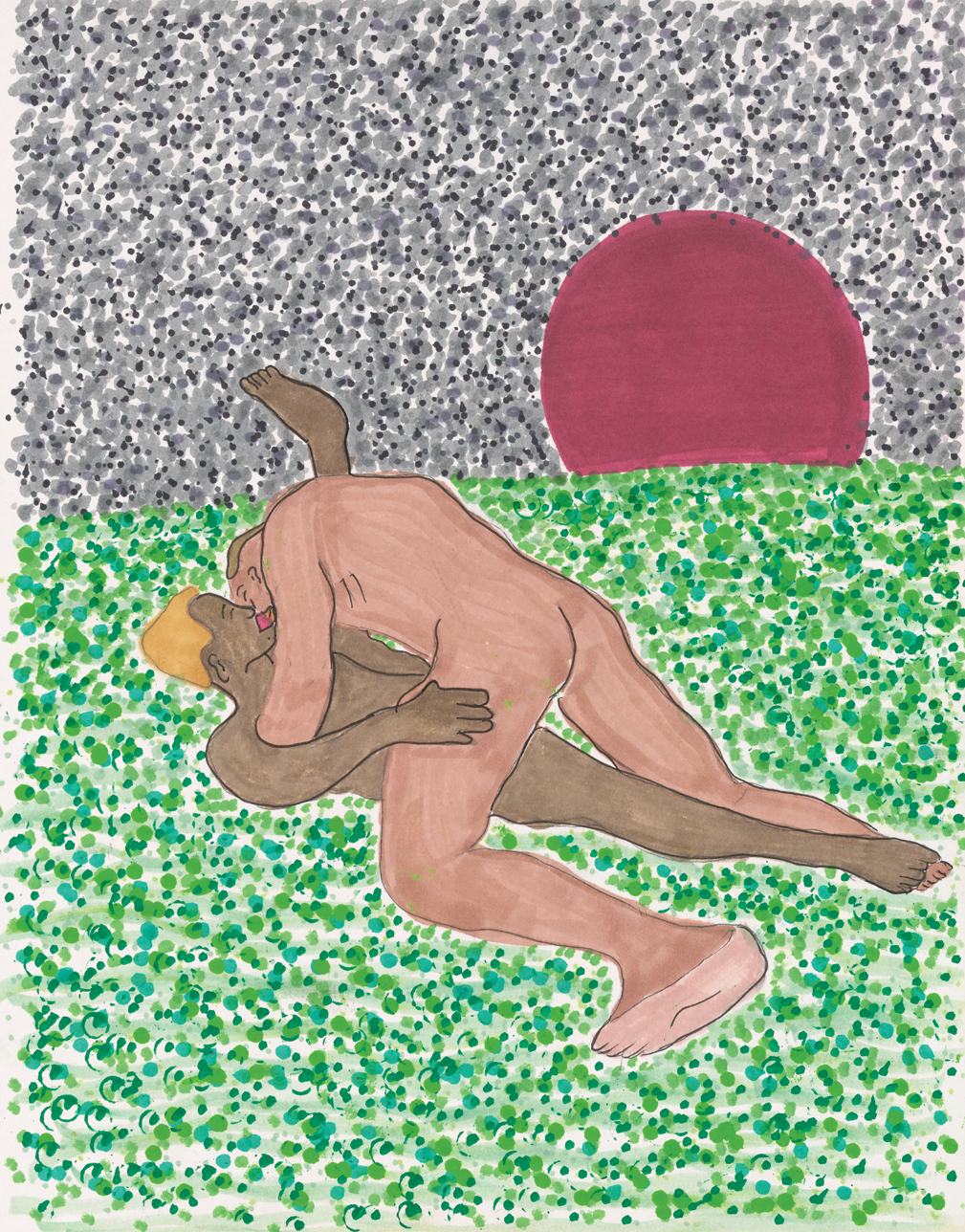

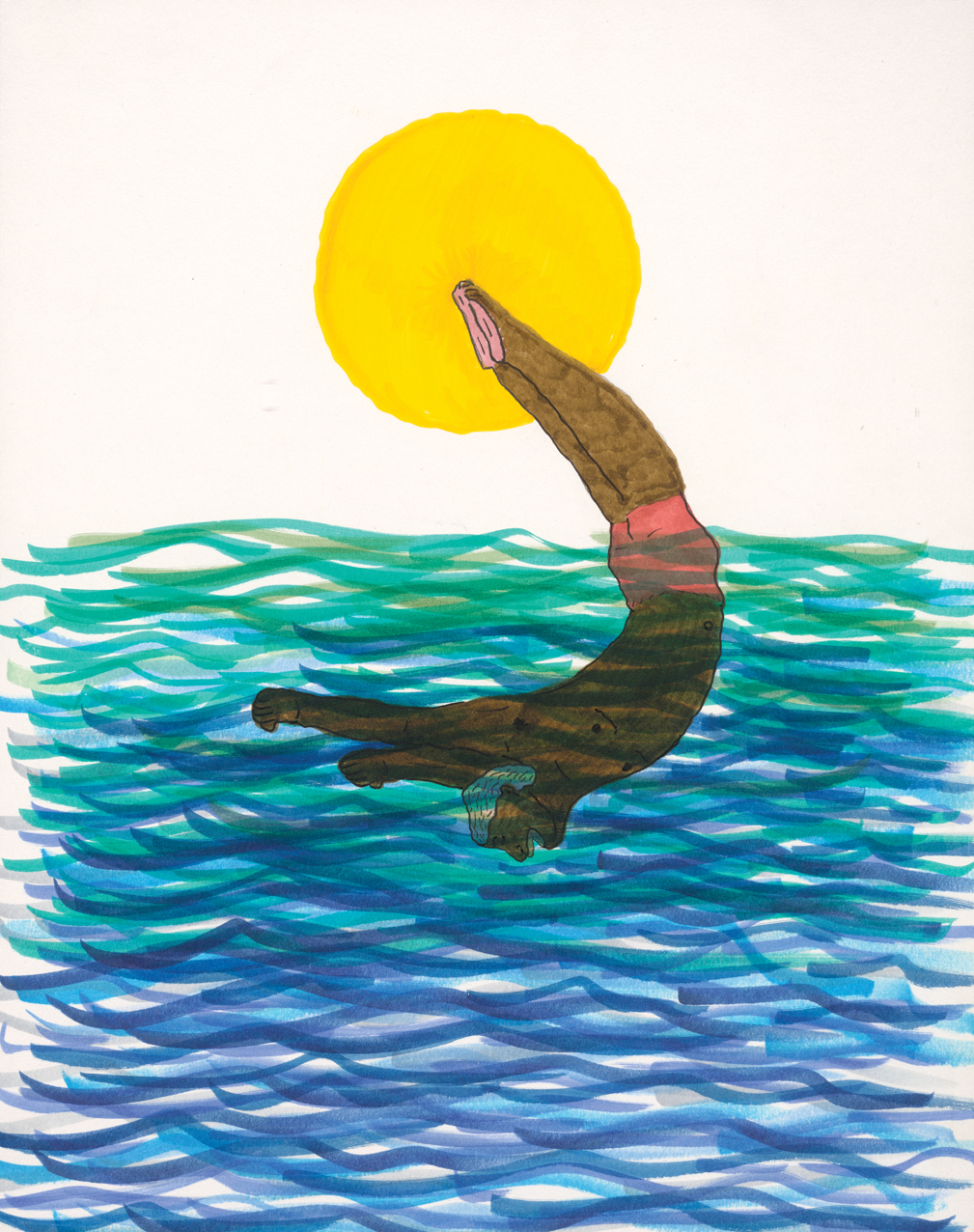

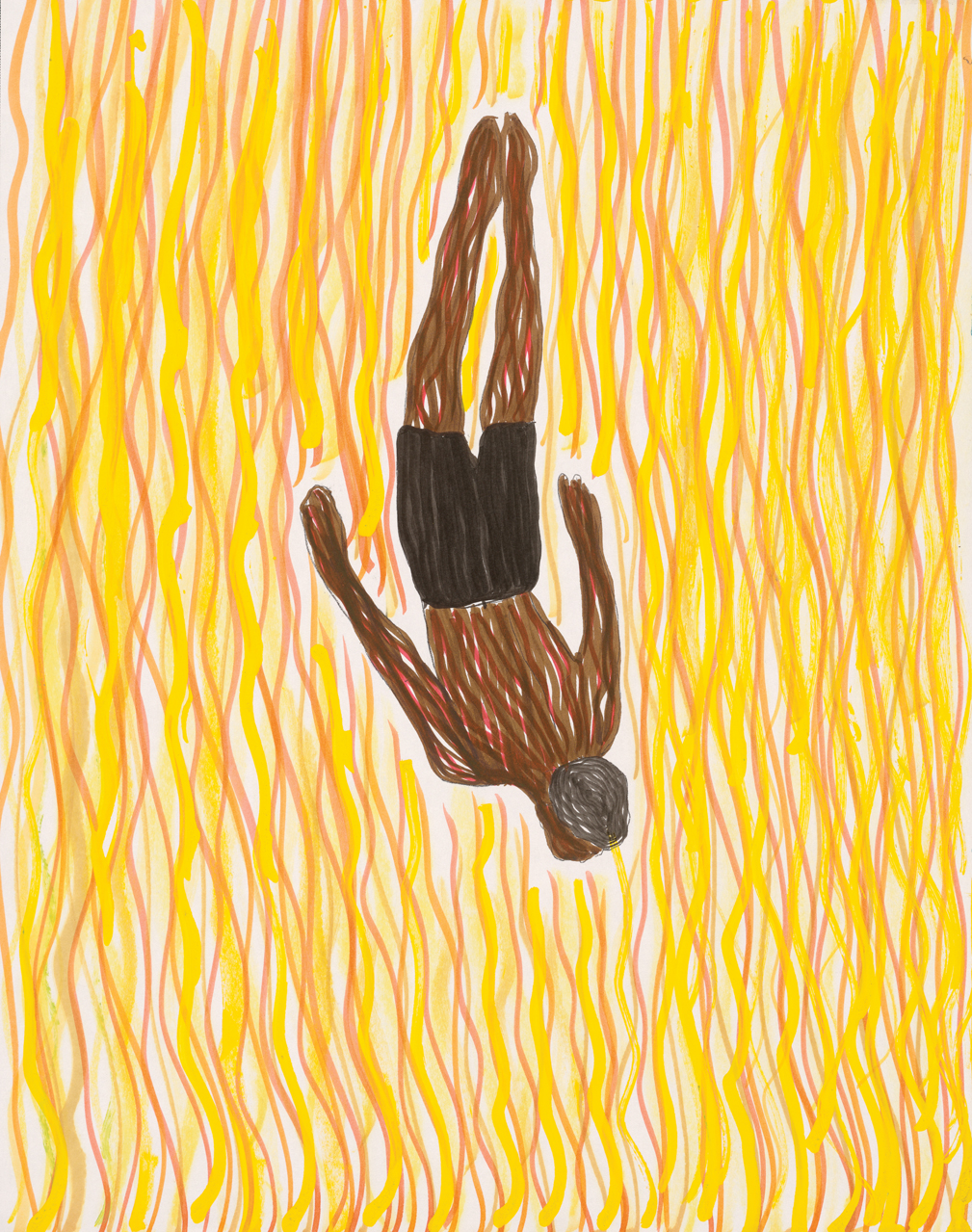

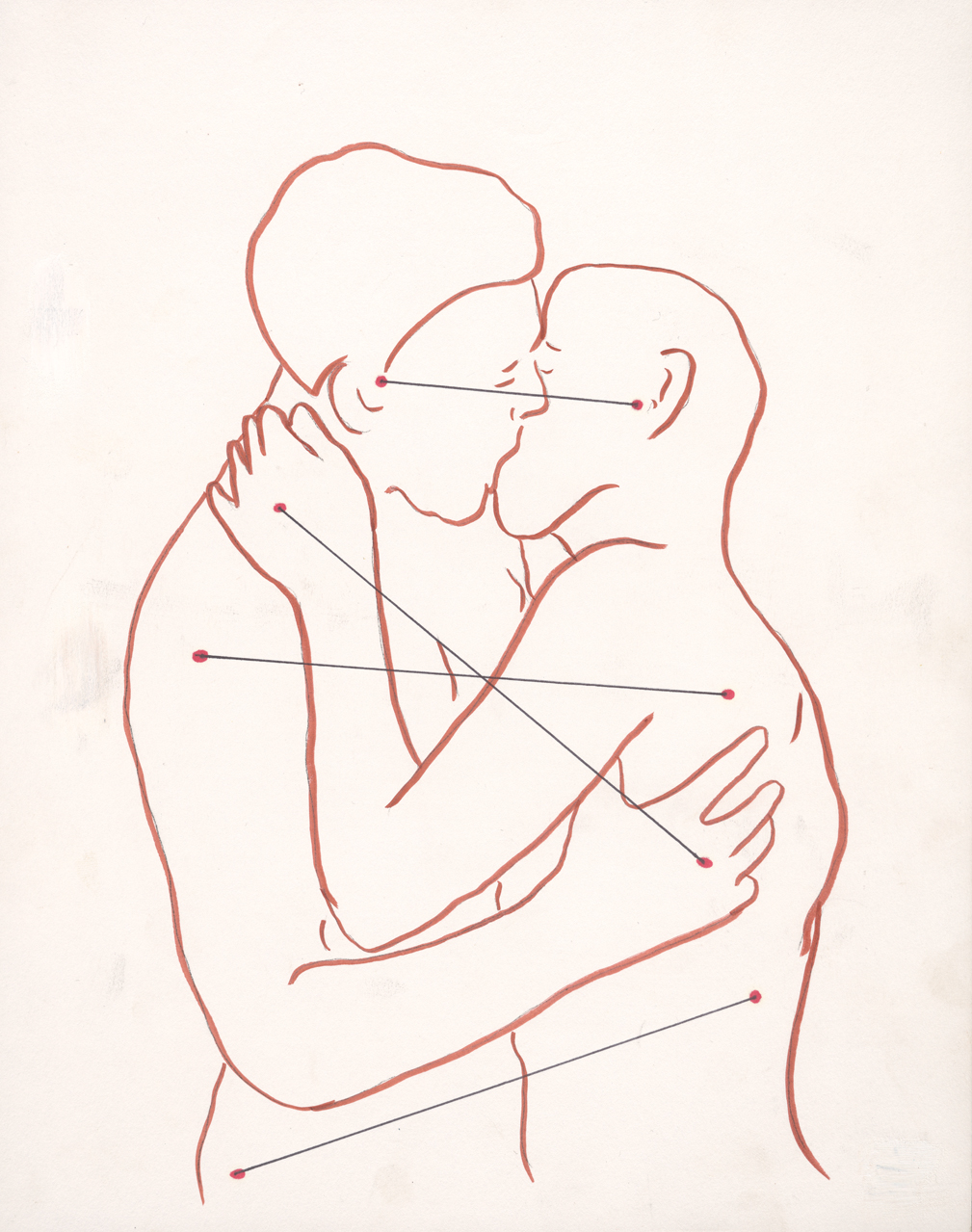

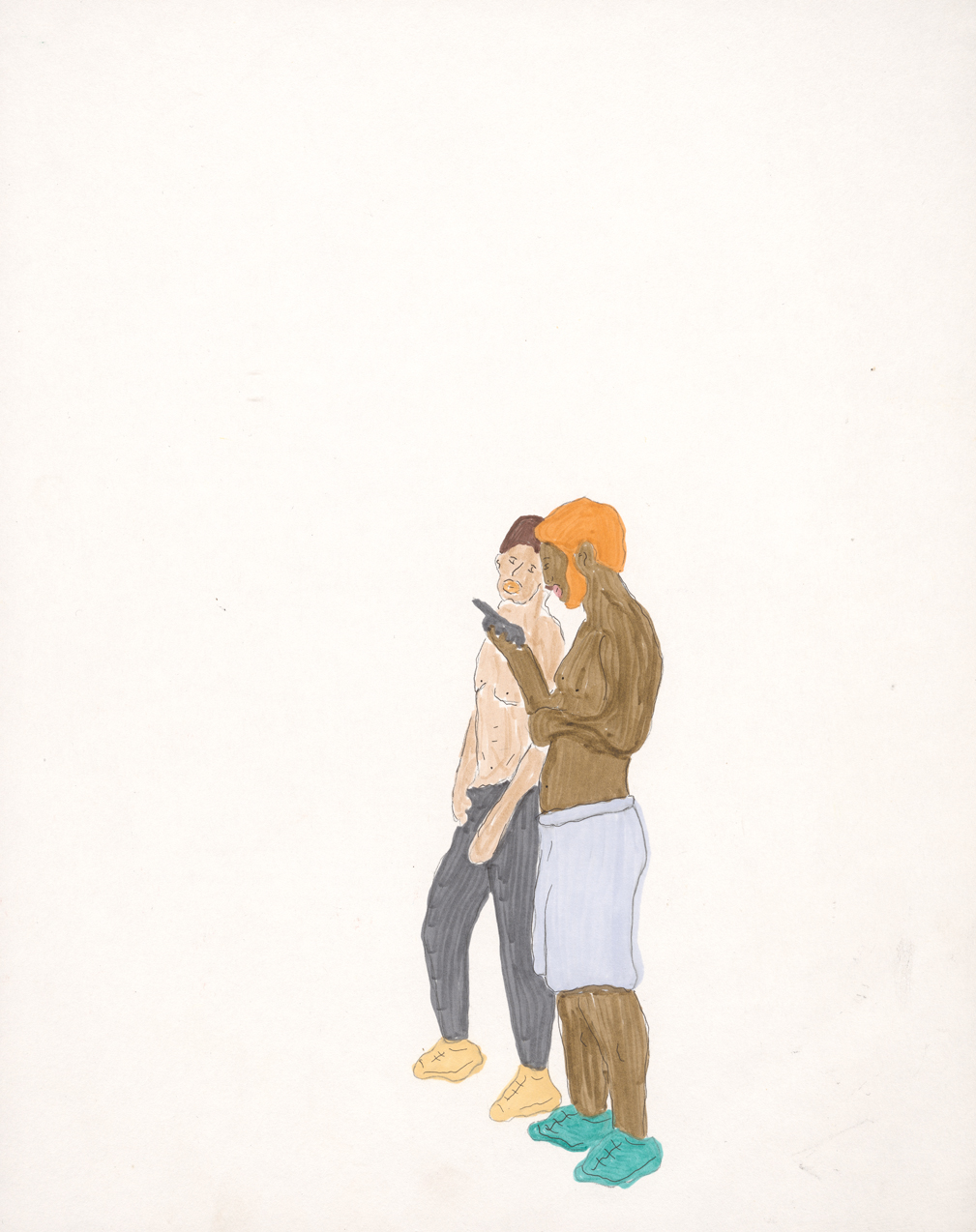

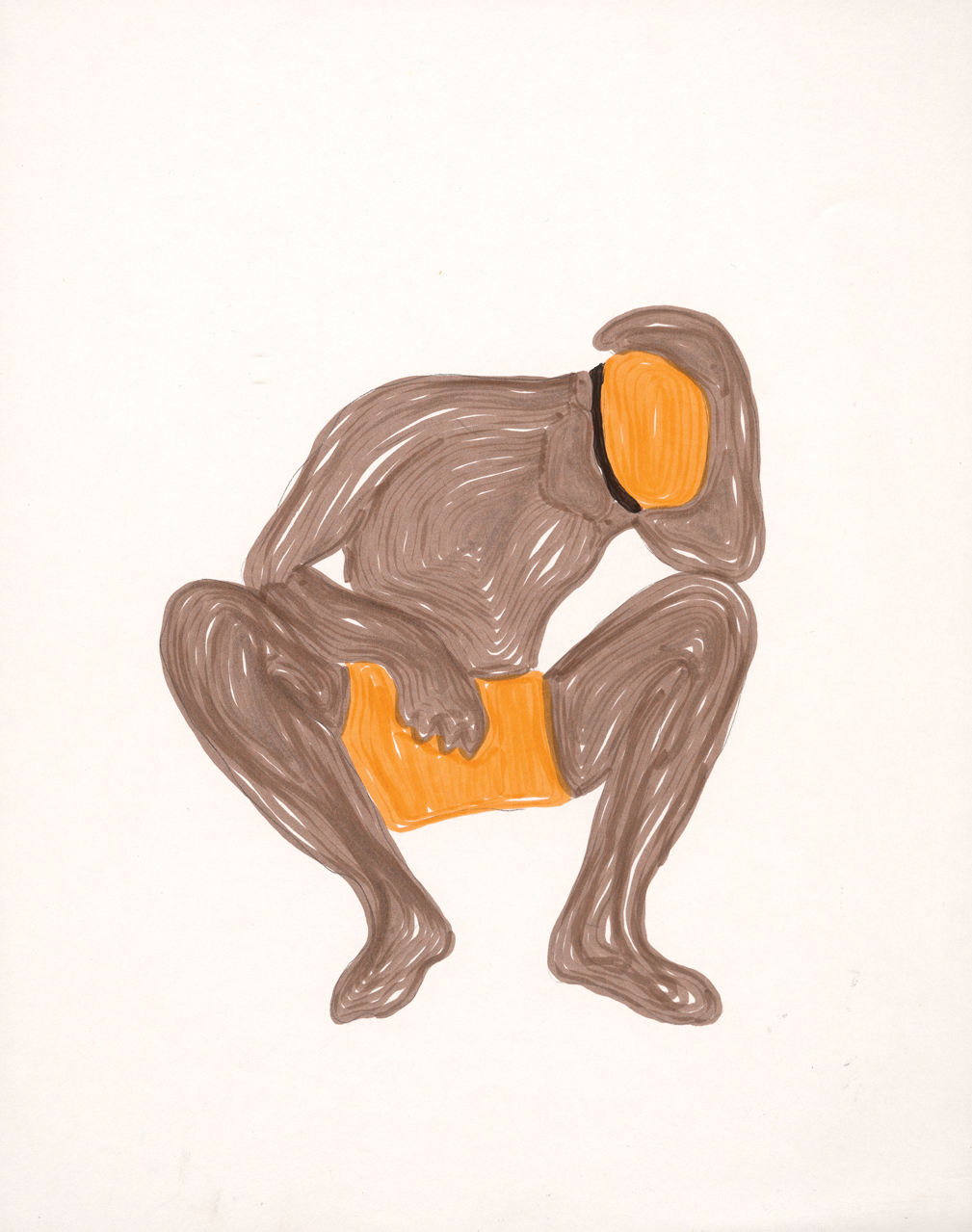

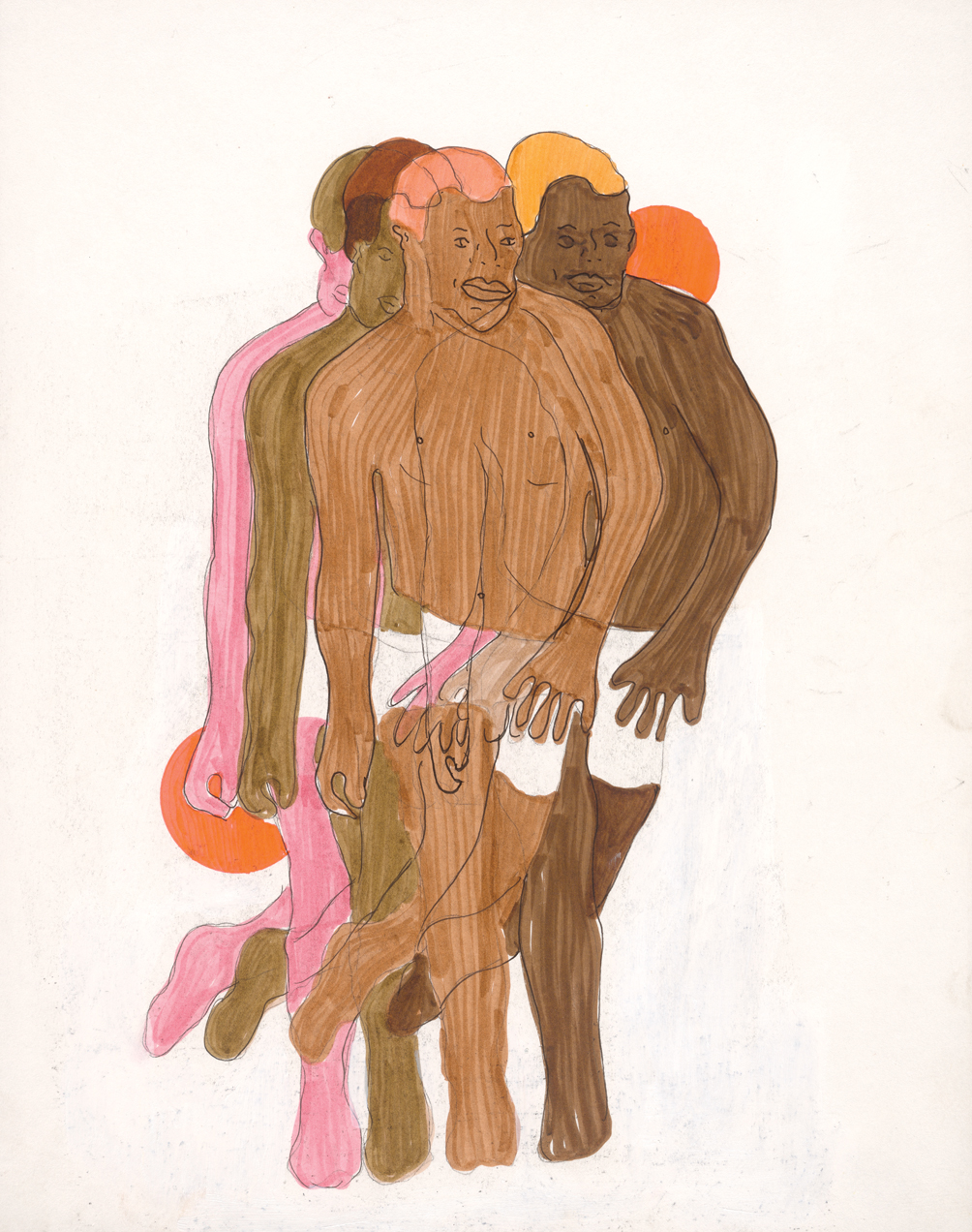

There is an accessibility to the work of Daniel Marcellus Givens that is rarely matched. His marker drawings of bodies radiating auras, colliding and fusing together, kissing, wrestling, dancing, or flying through the air, in their abstraction, are at once both mysterious and instantly identifiable. They are unpretentious in their simplicity, being as much about the unfussy materiality of marker on paper as the metaphysics of meditation and love — difficult to describe, but easy to know once experienced.

Growing up as an ‘80s child in Chicago, Givens was raised by MTV. He digested music videos as multidimensional art, exhilarated by their combination of catchy melodies, poetic lyrics, and hypnotic visuals that satisfy the senses and saturate mass culture. He often sat in the DJ booth as his brother spun tracks for parties, and later with a drum machine and keyboard sampler, he became a DJ too and also made his own music. “As a little kid, one of my best friends and I were really into Prince,” he remembers. “We watched Purple Rain every day for a whole summer. We were way too young, but I had a friend who could get us into the movie theater.” Later Givens and that friend decided to start a band. “We didn’t have any instruments, so we decided to make them with some markers and construction paper. We copied the [artist formerly known as Prince] symbol-shaped guitar, using rulers as the guitar necks. We’d hang out in the backyard lip-syncing to Prince songs. That was my introduction to making art.”

Givens grew up as Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat were becoming household names. He admired their pop sensibilities, appreciating how they were able to translate art into the mass production of T-shirts, buttons, and postcards. “But I never thought I would make art as a career,” he says, “I didn’t think of myself as an artist. I didn’t take any drawing lessons in school. I took music lessons and later really got into film, thinking I would either end up in music or I would become a cinematographer.” He moved to New York in 2000, living in Brooklyn, then Queens, and finally settling in Harlem. It was there, over a decade after moving to the city, that he began his portfolio of marker drawings. Part documentary and part fantasy, his subjects developed. “I was really attracted to the vibrancy of Harlem at that time, to the personalities and colors. I started drawing to create my own society of people, all character-based.”

Givens describes drawing as a process of streamlining form. His works began at postcard size, and he reduced his figures to their essence, bodies contrasting the white paper backgrounds he left bare. He focused on the nuances of posture, his silhouettes suggesting a leg lifted to jump or an arm rested on a hip. Today he finds inspiration wherever it strikes, sneaking photos of people on the street and at his gym. His forms are dynamic and magical; he is fascinated by the idea of levitation, floating or flying. As an admirer of acrobatics and gymnastics, he often sources photos of contorted and outstretched bodies from Instagram.

Pornography also offers him a range of intertwined positions. He pauses sex acts when he is charmed by a particular formation, an ecstatic kiss or a romantic grip, often wondering about the line between business and pleasure, whether what he’s watching is strictly professional or a genuine moment of satisfaction and unity.

Much of Givens’s work is dedicated to black and brown men, or more precisely, men of color. The spectrum of skin tones in New York is something he has always found intriguingly beautiful. He explains, “After a while, I noticed a trend among black artists, that their characters were always black. Not brown, not shades. Usually black. Like Kerry James Marshall, who I love. Some of his stuff, the boys are black. The actual color is black. Noticing that in so many different artists’ work, it became important for me to show the spectrum.” As he infuses his infatuation with New Yorkers into his art, many men have played the role of muse. Each drawing is a love letter. He wants to capture that feeling of being on the train and thinking, “Oh my god! I’ve never seen anyone who looks like that.”

Working as a personal trainer and yoga teacher led Givens to the study of anatomy, and the time he spent poring over books on muscular and skeletal systems began to permeate his drawing style. Going more than skin deep, his forms often show nerves and muscle fibers abstracted into striated lines. “Because a lot of my art is about black and brown men, at a certain point, I wanted to even strip that away, where it’s not about that. It’s just about a human form.”

As time passed, Givens began adding backgrounds to his compositions. He wanted to expand the worlds he created for his figures by inserting them into atmospheric environments, mostly hazy colors, shapes, and patterns, implying a mood and space without defining it in a recognizable way. Glowing orbs and beams of light often accent the scenery, symbols of energetic power. The settings anchor their inhabitants, allowing them to dive and skip through dream-like backdrops.

So much of the art world is wrapped up in capitalism, in making distinctions between high and low, established and outsider, eastern and western, but Givens’s work defies these qualifications. Finding a sense of belonging in the commercial art world has been a bumpy road for him. “I have a love-hate relationship with the art world,” he admits, “I kept having the experience of being at a show at a gallery in Chelsea, and there’d be a black artist on the walls and I’d be the only black person in the space. A couple of times I walked into rooms while a white gallerist was describing what they thought a black artist was doing or saying. It felt awkward, but eventually I flipped it where it became an empowering thing for me. I told myself that I deserved to be there, that the gallery actually needed me to be there to see the work.”

For Givens, drawing is an outlet, an opportunity to look closely at the world around him and transform his individual experiences into unifying gestures filled with nuance and devotion. Still he yearns for a return to his musical and cinephile roots. He sees the possibility of his artistry coming full-circle, connecting these different mediums through installation, staging complex and multilayered experiences. He explains, “Right now, I don’t have the space or the luxury to make something that’s twenty-feet tall, but that’s what I see for the future.”

Daniel Marcellus Givens photographed by Christopher Tomas, Harlem, New York. May 2020.

Daniel Marcellus Givens photographed by Christopher Tomas, Harlem, New York. May 2020.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 12, get a copy here.