Daniel Rampulla: Wild Place

A photographer exposes his desires and his pains of coming out.

TEXT BY CHRIS STEWART

PHOTOGRAPHY BY DANIEL RAMPULLA

Smizing, (2018).

All of the photographs in “Wild Place,” Daniel Rampulla’s first solo show in New York, do not quickly deliver their message. The differentiation of light in black and white photographs can have a chilling effect, as they do in this small, thoughtful show. Monochromatic photographs may eliminate immediate context for viewers, where color may provide a natural cache of reference. The comfort of color is not to be found in these photographs, though being hung close together helps develop a rich narrative of discovery inside of the frame. There are trees captured at night using harsh flashes; there are trees captured using daylight’s passing shadows. The trees are isolated in the frame, and when exposed, seem like unsuspecting neighbors caught naked through an opened window. Bodies are also exposed in Rampulla’s work, and these figures flank the trees. Nature, through Rampulla’s lens, is in a susceptible state.

“Wild Place” was difficult to create, he told me. It is some of Rampulla’s most intimate work to date. After a trip back home to the Bay Area, he began dredging up latent feelings of pain and fear attached to being closeted. He’d discovered himself in nature, and wanted to shed some light on that specific time in his life. By returning to familiar landscapes, like the Meat Rack on Fire Island, or the woods behind his parents’ home, he hoped to uncage himself from those adolescent fears and expose desires he’d hid for too long.

Presented in the same format across two walls, the photographs entangle each other, bodies and tree-limbs becoming fragments of the same scene. The effect is charming. Using technical lighting skills and no-fuss compositions, setting complies into subject and allows an evocative narrative to remain non-intrusive, allowing for endless possibility inside and outside of the frame.

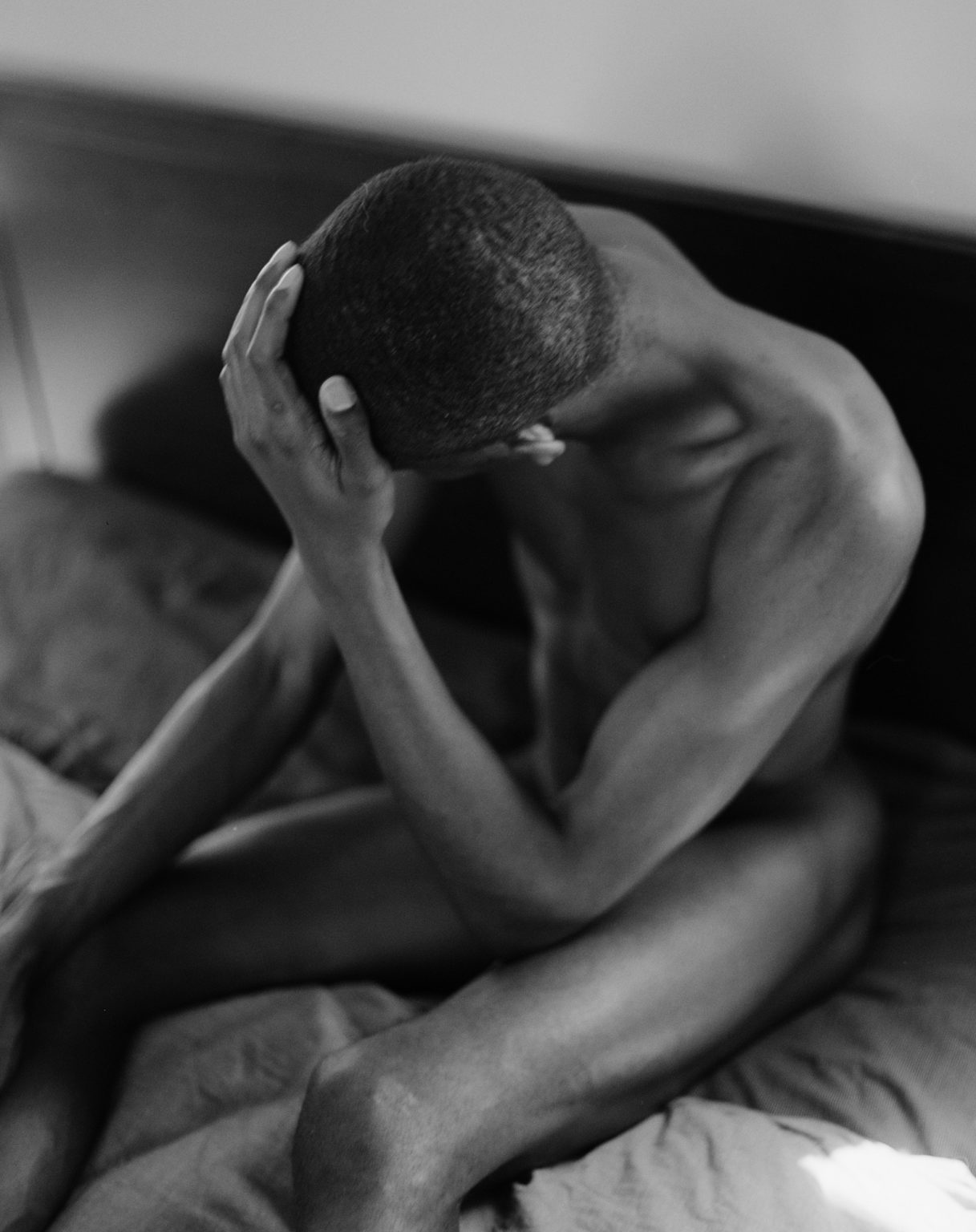

In “Wild Place,” faces are turned away or hidden from view. The body, then, becomes a tool to discuss accumulated experience. One of the more arresting images in the show, “Smizing,” performs this emotional-accumulation best. In a gesture of exasperation, the model’s face is hidden inside the crux of their elbow and long hair covers their arms’ definition. This posture seems to roleplay emotion — sadness, specifically — rather than convey it directly with the model’s facial expression. With faces continuously hidden, the body provides more formal context, allowing postures to universalize emotional suggestions. In “Nicky, Late Afternoon” and “Last Light,” the models turn toward the natural light streaming in from outside the frame. Their postures are stable, using the support of the space around them respectively to give each image a quiet power. With faces out of view, judgements may not be easily passed by the viewer. Deliverance is somewhere in solitude, or again, some place outside the presented frame.

Together, the photographs contextualize the sexual and emotional profundity of coming out, of having that first sexual experience and then dealing with it, most likely in private, plus evoking a predisposed guilt, or shame. The choice to keep faces hidden could suggest varying levels of guilt or shame, but those feelings did not remain with me. Popular gay male portraiture often elicits shockvalue from the seemingly perverse intimacy implicit between male bodies. Rampulla forgoes this trope, choosing the emotional over the physical. In “Charles, Bay Window” (2018), a nude model is seen from behind, contemplative in his posture suggesting a moment of introspection before two windows. The model, who is bare-assed in the foreground, is not distracted by his own nudity. He is the sole participant in the scene, and will continue to be long after the viewer is gone. “Wild Place” seemed less concerned with the present rather than what would remain with its witnesses after they’ve left the gallery. I know there are many ways to capture vulnerable bodies, and I was reminded there are many ways to discover the values of hidden spaces. I was reminded of the late Alvin Baltrop, how his photographs of the bygone west side piers both avenged and memorialized a generation lost to AIDS. I also thought of the PaJaMa collective, and their idiosyncratic portraits taken on Fire Island in the ‘30s and ‘40s that serialized early queer-taste. The stories in these photographs are not mine, but somehow I am nostalgic for them.

After a long stint inside during the pandemic, I arrived at the gallery and was ushered down a flight of stairs into the gallery’s shadow space. In the basement, Rampulla and I chatted about the past six months as the photos quietly hung on the walls. When I turned my attention to them, I began to forget where I was, the photos becoming places I felt I’d seen. For a moment, I entered that strange place available to all of us. Standing before a photograph I didn’t take in a place I’d never been — familiar to my surroundings, I was lost somewhere inside of myself.

“Wild Place” is the inaugural exhibit for PROJECTION, a new initiative alongside Chart’s main gallery programming, highlighting diverse voices in intimate presentations.

On view through September 26th. Monday-Friday, by appointment. Chart, 74 Franklin St., NY, NY 10013.

All images courtesy of the artist and CHART.

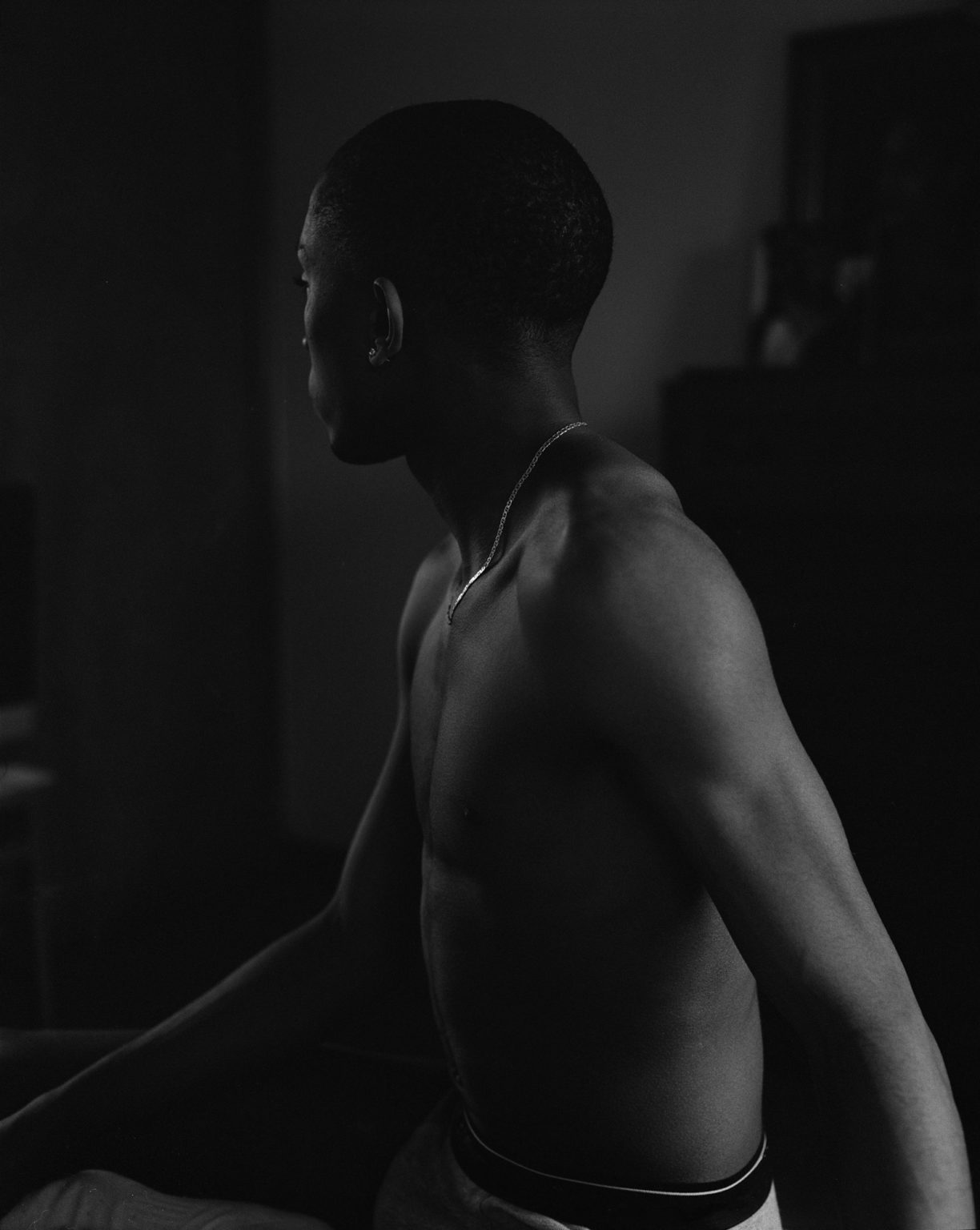

Nicky, Late Afternoon, (2019).

All of the photographs in “Wild Place,” Daniel Rampulla’s first solo show in New York, do not quickly deliver their message. The differentiation of light in black and white photographs can have a chilling effect, as they do in this small, thoughtful show. Monochromatic photographs may eliminate immediate context for viewers, where color may provide a natural cache of reference. The comfort of color is not to be found in these photographs, though being hung close together helps develop a rich narrative of discovery inside of the frame. There are trees captured at night using harsh flashes; there are trees captured using daylight’s passing shadows. The trees are isolated in the frame, and when exposed, seem like unsuspecting neighbors caught naked through an opened window. Bodies are also exposed in Rampulla’s work, and these figures flank the trees. Nature, through Rampulla’s lens, is in a susceptible state.

“Wild Place” was difficult to create, he told me. It is some of Rampulla’s most intimate work to date. After a trip back home to the Bay Area, he began dredging up latent feelings of pain and fear attached to being closeted. He’d discovered himself in nature, and wanted to shed some light on that specific time in his life. By returning to familiar landscapes, like the Meat Rack on Fire Island, or the woods behind his parents’ home, he hoped to uncage himself from those adolescent fears and expose desires he’d hid for too long.

Presented in the same format across two walls, the photographs entangle each other, bodies and tree-limbs becoming fragments of the same scene. The effect is charming. Using technical lighting skills and no-fuss compositions, setting complies into subject and allows an evocative narrative to remain non-intrusive, allowing for endless possibility inside and outside of the frame.

In “Wild Place,” faces are turned away or hidden from view. The body, then, becomes a tool to discuss accumulated experience. One of the more arresting images in the show, “Smizing,” performs this emotional-accumulation best. In a gesture of exasperation, the model’s face is hidden inside the crux of their elbow and long hair covers their arms’ definition. This posture seems to roleplay emotion — sadness, specifically — rather than convey it directly with the model’s facial expression. With faces continuously hidden, the body provides more formal context, allowing postures to universalize emotional suggestions. In “Nicky, Late Afternoon” and “Last Light,” the models turn toward the natural light streaming in from outside the frame. Their postures are stable, using the support of the space around them respectively to give each image a quiet power. With faces out of view, judgements may not be easily passed by the viewer. Deliverance is somewhere in solitude, or again, some place outside the presented frame.

Together, the photographs contextualize the sexual and emotional profundity of coming out, of having that first sexual experience and then dealing with it, most likely in private, plus evoking a predisposed guilt, or shame. The choice to keep faces hidden could suggest varying levels of guilt or shame, but those feelings did not remain with me. Popular gay male portraiture often elicits shockvalue from the seemingly perverse intimacy implicit between male bodies. Rampulla forgoes this trope, choosing the emotional over the physical. In “Charles, Bay Window” (2018), a nude model is seen from behind, contemplative in his posture suggesting a moment of introspection before two windows. The model, who is bare-assed in the foreground, is not distracted by his own nudity. He is the sole participant in the scene, and will continue to be long after the viewer is gone. “Wild Place” seemed less concerned with the present rather than what would remain with its witnesses after they’ve left the gallery. I know there are many ways to capture vulnerable bodies, and I was reminded there are many ways to discover the values of hidden spaces. I was reminded of the late Alvin Baltrop, how his photographs of the bygone west side piers both avenged and memorialized a generation lost to AIDS. I also thought of the PaJaMa collective, and their idiosyncratic portraits taken on Fire Island in the ‘30s and ‘40s that serialized early queer-taste. The stories in these photographs are not mine, but somehow I am nostalgic for them.

After a long stint inside during the pandemic, I arrived at the gallery and was ushered down a flight of stairs into the gallery’s shadow space. In the basement, Rampulla and I chatted about the past six months as the photos quietly hung on the walls. When I turned my attention to them, I began to forget where I was, the photos becoming places I felt I’d seen. For a moment, I entered that strange place available to all of us. Standing before a photograph I didn’t take in a place I’d never been — familiar to my surroundings, I was lost somewhere inside of myself.

“Wild Place” is the inaugural exhibit for PROJECTION, a new initiative alongside Chart’s main gallery programming, highlighting diverse voices in intimate presentations.

On view through September 26th. Monday-Friday, by appointment. Chart, 74 Franklin St., NY, NY 10013.

All images courtesy of the artist and CHART.

Memorial Highway, (2019).

All of the photographs in “Wild Place,” Daniel Rampulla’s first solo show in New York, do not quickly deliver their message. The differentiation of light in black and white photographs can have a chilling effect, as they do in this small, thoughtful show. Monochromatic photographs may eliminate immediate context for viewers, where color may provide a natural cache of reference. The comfort of color is not to be found in these photographs, though being hung close together helps develop a rich narrative of discovery inside of the frame. There are trees captured at night using harsh flashes; there are trees captured using daylight’s passing shadows. The trees are isolated in the frame, and when exposed, seem like unsuspecting neighbors caught naked through an opened window. Bodies are also exposed in Rampulla’s work, and these figures flank the trees. Nature, through Rampulla’s lens, is in a susceptible state.

“Wild Place” was difficult to create, he told me. It is some of Rampulla’s most intimate work to date. After a trip back home to the Bay Area, he began dredging up latent feelings of pain and fear attached to being closeted. He’d discovered himself in nature, and wanted to shed some light on that specific time in his life. By returning to familiar landscapes, like the Meat Rack on Fire Island, or the woods behind his parents’ home, he hoped to uncage himself from those adolescent fears and expose desires he’d hid for too long.

Presented in the same format across two walls, the photographs entangle each other, bodies and tree-limbs becoming fragments of the same scene. The effect is charming. Using technical lighting skills and no-fuss compositions, setting complies into subject and allows an evocative narrative to remain non-intrusive, allowing for endless possibility inside and outside of the frame.

In “Wild Place,” faces are turned away or hidden from view. The body, then, becomes a tool to discuss accumulated experience. One of the more arresting images in the show, “Smizing,” performs this emotional-accumulation best. In a gesture of exasperation, the model’s face is hidden inside the crux of their elbow and long hair covers their arms’ definition. This posture seems to roleplay emotion — sadness, specifically — rather than convey it directly with the model’s facial expression. With faces continuously hidden, the body provides more formal context, allowing postures to universalize emotional suggestions. In “Nicky, Late Afternoon” and “Last Light,” the models turn toward the natural light streaming in from outside the frame. Their postures are stable, using the support of the space around them respectively to give each image a quiet power. With faces out of view, judgements may not be easily passed by the viewer. Deliverance is somewhere in solitude, or again, some place outside the presented frame.

Together, the photographs contextualize the sexual and emotional profundity of coming out, of having that first sexual experience and then dealing with it, most likely in private, plus evoking a predisposed guilt, or shame. The choice to keep faces hidden could suggest varying levels of guilt or shame, but those feelings did not remain with me. Popular gay male portraiture often elicits shockvalue from the seemingly perverse intimacy implicit between male bodies. Rampulla forgoes this trope, choosing the emotional over the physical. In “Charles, Bay Window” (2018), a nude model is seen from behind, contemplative in his posture suggesting a moment of introspection before two windows. The model, who is bare-assed in the foreground, is not distracted by his own nudity. He is the sole participant in the scene, and will continue to be long after the viewer is gone. “Wild Place” seemed less concerned with the present rather than what would remain with its witnesses after they’ve left the gallery. I know there are many ways to capture vulnerable bodies, and I was reminded there are many ways to discover the values of hidden spaces. I was reminded of the late Alvin Baltrop, how his photographs of the bygone west side piers both avenged and memorialized a generation lost to AIDS. I also thought of the PaJaMa collective, and their idiosyncratic portraits taken on Fire Island in the ‘30s and ‘40s that serialized early queer-taste. The stories in these photographs are not mine, but somehow I am nostalgic for them.

After a long stint inside during the pandemic, I arrived at the gallery and was ushered down a flight of stairs into the gallery’s shadow space. In the basement, Rampulla and I chatted about the past six months as the photos quietly hung on the walls. When I turned my attention to them, I began to forget where I was, the photos becoming places I felt I’d seen. For a moment, I entered that strange place available to all of us. Standing before a photograph I didn’t take in a place I’d never been — familiar to my surroundings, I was lost somewhere inside of myself.

“Wild Place” is the inaugural exhibit for PROJECTION, a new initiative alongside Chart’s main gallery programming, highlighting diverse voices in intimate presentations.

On view through September 26th. Monday-Friday, by appointment. Chart, 74 Franklin St., NY, NY 10013.

All images courtesy of the artist and CHART.

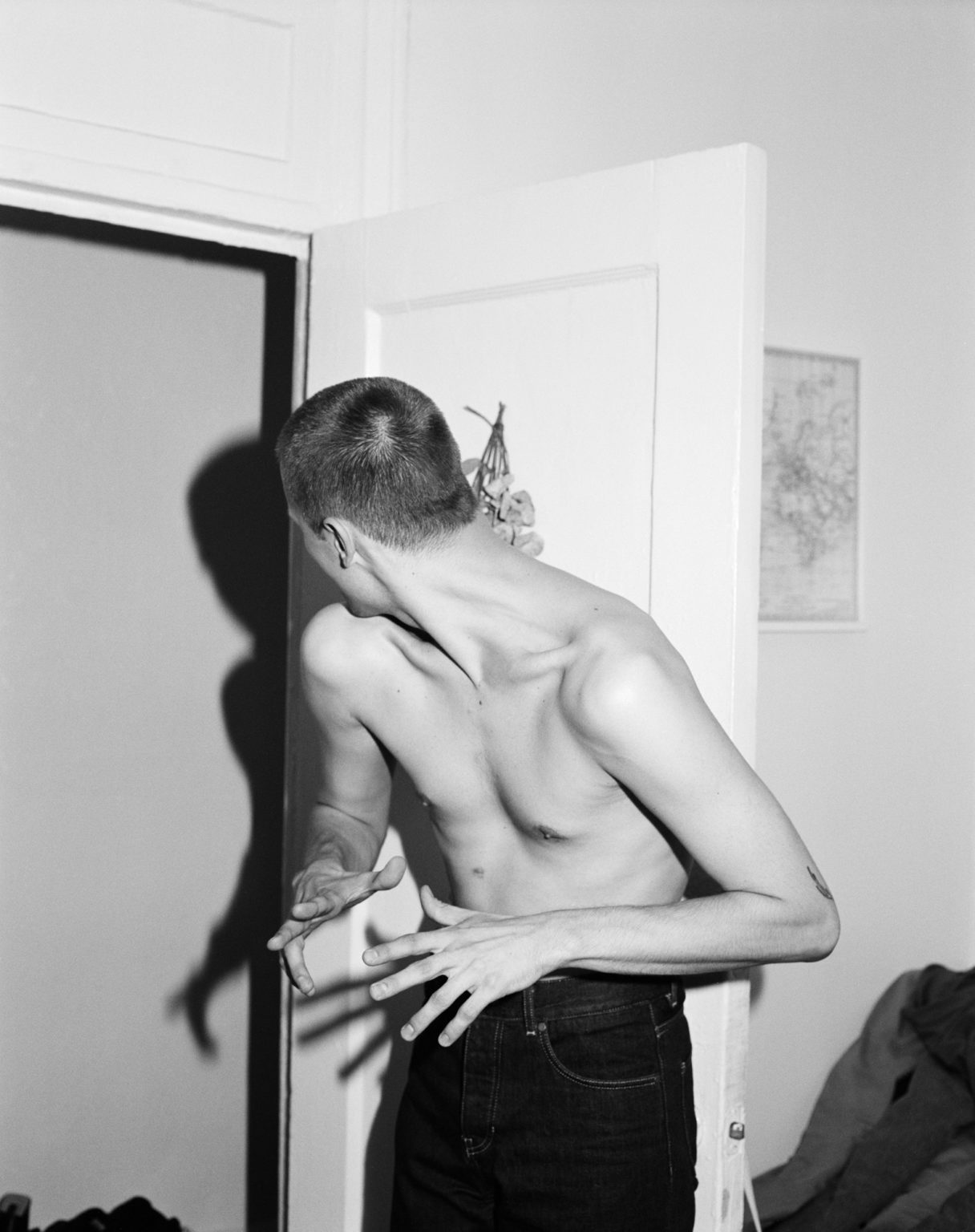

Evan, Shadow, (2017).

All of the photographs in “Wild Place,” Daniel Rampulla’s first solo show in New York, do not quickly deliver their message. The differentiation of light in black and white photographs can have a chilling effect, as they do in this small, thoughtful show. Monochromatic photographs may eliminate immediate context for viewers, where color may provide a natural cache of reference. The comfort of color is not to be found in these photographs, though being hung close together helps develop a rich narrative of discovery inside of the frame. There are trees captured at night using harsh flashes; there are trees captured using daylight’s passing shadows. The trees are isolated in the frame, and when exposed, seem like unsuspecting neighbors caught naked through an opened window. Bodies are also exposed in Rampulla’s work, and these figures flank the trees. Nature, through Rampulla’s lens, is in a susceptible state.

“Wild Place” was difficult to create, he told me. It is some of Rampulla’s most intimate work to date. After a trip back home to the Bay Area, he began dredging up latent feelings of pain and fear attached to being closeted. He’d discovered himself in nature, and wanted to shed some light on that specific time in his life. By returning to familiar landscapes, like the Meat Rack on Fire Island, or the woods behind his parents’ home, he hoped to uncage himself from those adolescent fears and expose desires he’d hid for too long.

Presented in the same format across two walls, the photographs entangle each other, bodies and tree-limbs becoming fragments of the same scene. The effect is charming. Using technical lighting skills and no-fuss compositions, setting complies into subject and allows an evocative narrative to remain non-intrusive, allowing for endless possibility inside and outside of the frame.

In “Wild Place,” faces are turned away or hidden from view. The body, then, becomes a tool to discuss accumulated experience. One of the more arresting images in the show, “Smizing,” performs this emotional-accumulation best. In a gesture of exasperation, the model’s face is hidden inside the crux of their elbow and long hair covers their arms’ definition. This posture seems to roleplay emotion — sadness, specifically — rather than convey it directly with the model’s facial expression. With faces continuously hidden, the body provides more formal context, allowing postures to universalize emotional suggestions. In “Nicky, Late Afternoon” and “Last Light,” the models turn toward the natural light streaming in from outside the frame. Their postures are stable, using the support of the space around them respectively to give each image a quiet power. With faces out of view, judgements may not be easily passed by the viewer. Deliverance is somewhere in solitude, or again, some place outside the presented frame.

Together, the photographs contextualize the sexual and emotional profundity of coming out, of having that first sexual experience and then dealing with it, most likely in private, plus evoking a predisposed guilt, or shame. The choice to keep faces hidden could suggest varying levels of guilt or shame, but those feelings did not remain with me. Popular gay male portraiture often elicits shockvalue from the seemingly perverse intimacy implicit between male bodies. Rampulla forgoes this trope, choosing the emotional over the physical. In “Charles, Bay Window” (2018), a nude model is seen from behind, contemplative in his posture suggesting a moment of introspection before two windows. The model, who is bare-assed in the foreground, is not distracted by his own nudity. He is the sole participant in the scene, and will continue to be long after the viewer is gone. “Wild Place” seemed less concerned with the present rather than what would remain with its witnesses after they’ve left the gallery. I know there are many ways to capture vulnerable bodies, and I was reminded there are many ways to discover the values of hidden spaces. I was reminded of the late Alvin Baltrop, how his photographs of the bygone west side piers both avenged and memorialized a generation lost to AIDS. I also thought of the PaJaMa collective, and their idiosyncratic portraits taken on Fire Island in the ‘30s and ‘40s that serialized early queer-taste. The stories in these photographs are not mine, but somehow I am nostalgic for them.

After a long stint inside during the pandemic, I arrived at the gallery and was ushered down a flight of stairs into the gallery’s shadow space. In the basement, Rampulla and I chatted about the past six months as the photos quietly hung on the walls. When I turned my attention to them, I began to forget where I was, the photos becoming places I felt I’d seen. For a moment, I entered that strange place available to all of us. Standing before a photograph I didn’t take in a place I’d never been — familiar to my surroundings, I was lost somewhere inside of myself.

“Wild Place” is the inaugural exhibit for PROJECTION, a new initiative alongside Chart’s main gallery programming, highlighting diverse voices in intimate presentations.

On view through September 26th. Monday-Friday, by appointment. Chart, 74 Franklin St., NY, NY 10013.

All images courtesy of the artist and CHART.

Oleander, (2018).

All of the photographs in “Wild Place,” Daniel Rampulla’s first solo show in New York, do not quickly deliver their message. The differentiation of light in black and white photographs can have a chilling effect, as they do in this small, thoughtful show. Monochromatic photographs may eliminate immediate context for viewers, where color may provide a natural cache of reference. The comfort of color is not to be found in these photographs, though being hung close together helps develop a rich narrative of discovery inside of the frame. There are trees captured at night using harsh flashes; there are trees captured using daylight’s passing shadows. The trees are isolated in the frame, and when exposed, seem like unsuspecting neighbors caught naked through an opened window. Bodies are also exposed in Rampulla’s work, and these figures flank the trees. Nature, through Rampulla’s lens, is in a susceptible state.

“Wild Place” was difficult to create, he told me. It is some of Rampulla’s most intimate work to date. After a trip back home to the Bay Area, he began dredging up latent feelings of pain and fear attached to being closeted. He’d discovered himself in nature, and wanted to shed some light on that specific time in his life. By returning to familiar landscapes, like the Meat Rack on Fire Island, or the woods behind his parents’ home, he hoped to uncage himself from those adolescent fears and expose desires he’d hid for too long.

Presented in the same format across two walls, the photographs entangle each other, bodies and tree-limbs becoming fragments of the same scene. The effect is charming. Using technical lighting skills and no-fuss compositions, setting complies into subject and allows an evocative narrative to remain non-intrusive, allowing for endless possibility inside and outside of the frame.

In “Wild Place,” faces are turned away or hidden from view. The body, then, becomes a tool to discuss accumulated experience. One of the more arresting images in the show, “Smizing,” performs this emotional-accumulation best. In a gesture of exasperation, the model’s face is hidden inside the crux of their elbow and long hair covers their arms’ definition. This posture seems to roleplay emotion — sadness, specifically — rather than convey it directly with the model’s facial expression. With faces continuously hidden, the body provides more formal context, allowing postures to universalize emotional suggestions. In “Nicky, Late Afternoon” and “Last Light,” the models turn toward the natural light streaming in from outside the frame. Their postures are stable, using the support of the space around them respectively to give each image a quiet power. With faces out of view, judgements may not be easily passed by the viewer. Deliverance is somewhere in solitude, or again, some place outside the presented frame.

Together, the photographs contextualize the sexual and emotional profundity of coming out, of having that first sexual experience and then dealing with it, most likely in private, plus evoking a predisposed guilt, or shame. The choice to keep faces hidden could suggest varying levels of guilt or shame, but those feelings did not remain with me. Popular gay male portraiture often elicits shockvalue from the seemingly perverse intimacy implicit between male bodies. Rampulla forgoes this trope, choosing the emotional over the physical. In “Charles, Bay Window” (2018), a nude model is seen from behind, contemplative in his posture suggesting a moment of introspection before two windows. The model, who is bare-assed in the foreground, is not distracted by his own nudity. He is the sole participant in the scene, and will continue to be long after the viewer is gone. “Wild Place” seemed less concerned with the present rather than what would remain with its witnesses after they’ve left the gallery. I know there are many ways to capture vulnerable bodies, and I was reminded there are many ways to discover the values of hidden spaces. I was reminded of the late Alvin Baltrop, how his photographs of the bygone west side piers both avenged and memorialized a generation lost to AIDS. I also thought of the PaJaMa collective, and their idiosyncratic portraits taken on Fire Island in the ‘30s and ‘40s that serialized early queer-taste. The stories in these photographs are not mine, but somehow I am nostalgic for them.

After a long stint inside during the pandemic, I arrived at the gallery and was ushered down a flight of stairs into the gallery’s shadow space. In the basement, Rampulla and I chatted about the past six months as the photos quietly hung on the walls. When I turned my attention to them, I began to forget where I was, the photos becoming places I felt I’d seen. For a moment, I entered that strange place available to all of us. Standing before a photograph I didn’t take in a place I’d never been — familiar to my surroundings, I was lost somewhere inside of myself.

“Wild Place” is the inaugural exhibit for PROJECTION, a new initiative alongside Chart’s main gallery programming, highlighting diverse voices in intimate presentations.

On view through September 26th. Monday-Friday, by appointment. Chart, 74 Franklin St., NY, NY 10013.

All images courtesy of the artist and CHART.

Pull Up, (2018).

All of the photographs in “Wild Place,” Daniel Rampulla’s first solo show in New York, do not quickly deliver their message. The differentiation of light in black and white photographs can have a chilling effect, as they do in this small, thoughtful show. Monochromatic photographs may eliminate immediate context for viewers, where color may provide a natural cache of reference. The comfort of color is not to be found in these photographs, though being hung close together helps develop a rich narrative of discovery inside of the frame. There are trees captured at night using harsh flashes; there are trees captured using daylight’s passing shadows. The trees are isolated in the frame, and when exposed, seem like unsuspecting neighbors caught naked through an opened window. Bodies are also exposed in Rampulla’s work, and these figures flank the trees. Nature, through Rampulla’s lens, is in a susceptible state.

“Wild Place” was difficult to create, he told me. It is some of Rampulla’s most intimate work to date. After a trip back home to the Bay Area, he began dredging up latent feelings of pain and fear attached to being closeted. He’d discovered himself in nature, and wanted to shed some light on that specific time in his life. By returning to familiar landscapes, like the Meat Rack on Fire Island, or the woods behind his parents’ home, he hoped to uncage himself from those adolescent fears and expose desires he’d hid for too long.

Presented in the same format across two walls, the photographs entangle each other, bodies and tree-limbs becoming fragments of the same scene. The effect is charming. Using technical lighting skills and no-fuss compositions, setting complies into subject and allows an evocative narrative to remain non-intrusive, allowing for endless possibility inside and outside of the frame.

In “Wild Place,” faces are turned away or hidden from view. The body, then, becomes a tool to discuss accumulated experience. One of the more arresting images in the show, “Smizing,” performs this emotional-accumulation best. In a gesture of exasperation, the model’s face is hidden inside the crux of their elbow and long hair covers their arms’ definition. This posture seems to roleplay emotion — sadness, specifically — rather than convey it directly with the model’s facial expression. With faces continuously hidden, the body provides more formal context, allowing postures to universalize emotional suggestions. In “Nicky, Late Afternoon” and “Last Light,” the models turn toward the natural light streaming in from outside the frame. Their postures are stable, using the support of the space around them respectively to give each image a quiet power. With faces out of view, judgements may not be easily passed by the viewer. Deliverance is somewhere in solitude, or again, some place outside the presented frame.

Together, the photographs contextualize the sexual and emotional profundity of coming out, of having that first sexual experience and then dealing with it, most likely in private, plus evoking a predisposed guilt, or shame. The choice to keep faces hidden could suggest varying levels of guilt or shame, but those feelings did not remain with me. Popular gay male portraiture often elicits shockvalue from the seemingly perverse intimacy implicit between male bodies. Rampulla forgoes this trope, choosing the emotional over the physical. In “Charles, Bay Window” (2018), a nude model is seen from behind, contemplative in his posture suggesting a moment of introspection before two windows. The model, who is bare-assed in the foreground, is not distracted by his own nudity. He is the sole participant in the scene, and will continue to be long after the viewer is gone. “Wild Place” seemed less concerned with the present rather than what would remain with its witnesses after they’ve left the gallery. I know there are many ways to capture vulnerable bodies, and I was reminded there are many ways to discover the values of hidden spaces. I was reminded of the late Alvin Baltrop, how his photographs of the bygone west side piers both avenged and memorialized a generation lost to AIDS. I also thought of the PaJaMa collective, and their idiosyncratic portraits taken on Fire Island in the ‘30s and ‘40s that serialized early queer-taste. The stories in these photographs are not mine, but somehow I am nostalgic for them.

After a long stint inside during the pandemic, I arrived at the gallery and was ushered down a flight of stairs into the gallery’s shadow space. In the basement, Rampulla and I chatted about the past six months as the photos quietly hung on the walls. When I turned my attention to them, I began to forget where I was, the photos becoming places I felt I’d seen. For a moment, I entered that strange place available to all of us. Standing before a photograph I didn’t take in a place I’d never been — familiar to my surroundings, I was lost somewhere inside of myself.

“Wild Place” is the inaugural exhibit for PROJECTION, a new initiative alongside Chart’s main gallery programming, highlighting diverse voices in intimate presentations.

On view through September 26th. Monday-Friday, by appointment. Chart, 74 Franklin St., NY, NY 10013.

All images courtesy of the artist and CHART.

Montes, Twist, (2019).

All of the photographs in “Wild Place,” Daniel Rampulla’s first solo show in New York, do not quickly deliver their message. The differentiation of light in black and white photographs can have a chilling effect, as they do in this small, thoughtful show. Monochromatic photographs may eliminate immediate context for viewers, where color may provide a natural cache of reference. The comfort of color is not to be found in these photographs, though being hung close together helps develop a rich narrative of discovery inside of the frame. There are trees captured at night using harsh flashes; there are trees captured using daylight’s passing shadows. The trees are isolated in the frame, and when exposed, seem like unsuspecting neighbors caught naked through an opened window. Bodies are also exposed in Rampulla’s work, and these figures flank the trees. Nature, through Rampulla’s lens, is in a susceptible state.

“Wild Place” was difficult to create, he told me. It is some of Rampulla’s most intimate work to date. After a trip back home to the Bay Area, he began dredging up latent feelings of pain and fear attached to being closeted. He’d discovered himself in nature, and wanted to shed some light on that specific time in his life. By returning to familiar landscapes, like the Meat Rack on Fire Island, or the woods behind his parents’ home, he hoped to uncage himself from those adolescent fears and expose desires he’d hid for too long.

Presented in the same format across two walls, the photographs entangle each other, bodies and tree-limbs becoming fragments of the same scene. The effect is charming. Using technical lighting skills and no-fuss compositions, setting complies into subject and allows an evocative narrative to remain non-intrusive, allowing for endless possibility inside and outside of the frame.

In “Wild Place,” faces are turned away or hidden from view. The body, then, becomes a tool to discuss accumulated experience. One of the more arresting images in the show, “Smizing,” performs this emotional-accumulation best. In a gesture of exasperation, the model’s face is hidden inside the crux of their elbow and long hair covers their arms’ definition. This posture seems to roleplay emotion — sadness, specifically — rather than convey it directly with the model’s facial expression. With faces continuously hidden, the body provides more formal context, allowing postures to universalize emotional suggestions. In “Nicky, Late Afternoon” and “Last Light,” the models turn toward the natural light streaming in from outside the frame. Their postures are stable, using the support of the space around them respectively to give each image a quiet power. With faces out of view, judgements may not be easily passed by the viewer. Deliverance is somewhere in solitude, or again, some place outside the presented frame.

Together, the photographs contextualize the sexual and emotional profundity of coming out, of having that first sexual experience and then dealing with it, most likely in private, plus evoking a predisposed guilt, or shame. The choice to keep faces hidden could suggest varying levels of guilt or shame, but those feelings did not remain with me. Popular gay male portraiture often elicits shockvalue from the seemingly perverse intimacy implicit between male bodies. Rampulla forgoes this trope, choosing the emotional over the physical. In “Charles, Bay Window” (2018), a nude model is seen from behind, contemplative in his posture suggesting a moment of introspection before two windows. The model, who is bare-assed in the foreground, is not distracted by his own nudity. He is the sole participant in the scene, and will continue to be long after the viewer is gone. “Wild Place” seemed less concerned with the present rather than what would remain with its witnesses after they’ve left the gallery. I know there are many ways to capture vulnerable bodies, and I was reminded there are many ways to discover the values of hidden spaces. I was reminded of the late Alvin Baltrop, how his photographs of the bygone west side piers both avenged and memorialized a generation lost to AIDS. I also thought of the PaJaMa collective, and their idiosyncratic portraits taken on Fire Island in the ‘30s and ‘40s that serialized early queer-taste. The stories in these photographs are not mine, but somehow I am nostalgic for them.

After a long stint inside during the pandemic, I arrived at the gallery and was ushered down a flight of stairs into the gallery’s shadow space. In the basement, Rampulla and I chatted about the past six months as the photos quietly hung on the walls. When I turned my attention to them, I began to forget where I was, the photos becoming places I felt I’d seen. For a moment, I entered that strange place available to all of us. Standing before a photograph I didn’t take in a place I’d never been — familiar to my surroundings, I was lost somewhere inside of myself.

“Wild Place” is the inaugural exhibit for PROJECTION, a new initiative alongside Chart’s main gallery programming, highlighting diverse voices in intimate presentations.

On view through September 26th. Monday-Friday, by appointment. Chart, 74 Franklin St., NY, NY 10013.

All images courtesy of the artist and CHART.

Charles, Bay Window, (2018).

All of the photographs in “Wild Place,” Daniel Rampulla’s first solo show in New York, do not quickly deliver their message. The differentiation of light in black and white photographs can have a chilling effect, as they do in this small, thoughtful show. Monochromatic photographs may eliminate immediate context for viewers, where color may provide a natural cache of reference. The comfort of color is not to be found in these photographs, though being hung close together helps develop a rich narrative of discovery inside of the frame. There are trees captured at night using harsh flashes; there are trees captured using daylight’s passing shadows. The trees are isolated in the frame, and when exposed, seem like unsuspecting neighbors caught naked through an opened window. Bodies are also exposed in Rampulla’s work, and these figures flank the trees. Nature, through Rampulla’s lens, is in a susceptible state.

“Wild Place” was difficult to create, he told me. It is some of Rampulla’s most intimate work to date. After a trip back home to the Bay Area, he began dredging up latent feelings of pain and fear attached to being closeted. He’d discovered himself in nature, and wanted to shed some light on that specific time in his life. By returning to familiar landscapes, like the Meat Rack on Fire Island, or the woods behind his parents’ home, he hoped to uncage himself from those adolescent fears and expose desires he’d hid for too long.

Presented in the same format across two walls, the photographs entangle each other, bodies and tree-limbs becoming fragments of the same scene. The effect is charming. Using technical lighting skills and no-fuss compositions, setting complies into subject and allows an evocative narrative to remain non-intrusive, allowing for endless possibility inside and outside of the frame.

In “Wild Place,” faces are turned away or hidden from view. The body, then, becomes a tool to discuss accumulated experience. One of the more arresting images in the show, “Smizing,” performs this emotional-accumulation best. In a gesture of exasperation, the model’s face is hidden inside the crux of their elbow and long hair covers their arms’ definition. This posture seems to roleplay emotion — sadness, specifically — rather than convey it directly with the model’s facial expression. With faces continuously hidden, the body provides more formal context, allowing postures to universalize emotional suggestions. In “Nicky, Late Afternoon” and “Last Light,” the models turn toward the natural light streaming in from outside the frame. Their postures are stable, using the support of the space around them respectively to give each image a quiet power. With faces out of view, judgements may not be easily passed by the viewer. Deliverance is somewhere in solitude, or again, some place outside the presented frame.

Together, the photographs contextualize the sexual and emotional profundity of coming out, of having that first sexual experience and then dealing with it, most likely in private, plus evoking a predisposed guilt, or shame. The choice to keep faces hidden could suggest varying levels of guilt or shame, but those feelings did not remain with me. Popular gay male portraiture often elicits shockvalue from the seemingly perverse intimacy implicit between male bodies. Rampulla forgoes this trope, choosing the emotional over the physical. In “Charles, Bay Window” (2018), a nude model is seen from behind, contemplative in his posture suggesting a moment of introspection before two windows. The model, who is bare-assed in the foreground, is not distracted by his own nudity. He is the sole participant in the scene, and will continue to be long after the viewer is gone. “Wild Place” seemed less concerned with the present rather than what would remain with its witnesses after they’ve left the gallery. I know there are many ways to capture vulnerable bodies, and I was reminded there are many ways to discover the values of hidden spaces. I was reminded of the late Alvin Baltrop, how his photographs of the bygone west side piers both avenged and memorialized a generation lost to AIDS. I also thought of the PaJaMa collective, and their idiosyncratic portraits taken on Fire Island in the ‘30s and ‘40s that serialized early queer-taste. The stories in these photographs are not mine, but somehow I am nostalgic for them.

After a long stint inside during the pandemic, I arrived at the gallery and was ushered down a flight of stairs into the gallery’s shadow space. In the basement, Rampulla and I chatted about the past six months as the photos quietly hung on the walls. When I turned my attention to them, I began to forget where I was, the photos becoming places I felt I’d seen. For a moment, I entered that strange place available to all of us. Standing before a photograph I didn’t take in a place I’d never been — familiar to my surroundings, I was lost somewhere inside of myself.

“Wild Place” is the inaugural exhibit for PROJECTION, a new initiative alongside Chart’s main gallery programming, highlighting diverse voices in intimate presentations.

On view through September 26th. Monday-Friday, by appointment. Chart, 74 Franklin St., NY, NY 10013.

All images courtesy of the artist and CHART.

Last Night, (2016).

All of the photographs in “Wild Place,” Daniel Rampulla’s first solo show in New York, do not quickly deliver their message. The differentiation of light in black and white photographs can have a chilling effect, as they do in this small, thoughtful show. Monochromatic photographs may eliminate immediate context for viewers, where color may provide a natural cache of reference. The comfort of color is not to be found in these photographs, though being hung close together helps develop a rich narrative of discovery inside of the frame. There are trees captured at night using harsh flashes; there are trees captured using daylight’s passing shadows. The trees are isolated in the frame, and when exposed, seem like unsuspecting neighbors caught naked through an opened window. Bodies are also exposed in Rampulla’s work, and these figures flank the trees. Nature, through Rampulla’s lens, is in a susceptible state.

“Wild Place” was difficult to create, he told me. It is some of Rampulla’s most intimate work to date. After a trip back home to the Bay Area, he began dredging up latent feelings of pain and fear attached to being closeted. He’d discovered himself in nature, and wanted to shed some light on that specific time in his life. By returning to familiar landscapes, like the Meat Rack on Fire Island, or the woods behind his parents’ home, he hoped to uncage himself from those adolescent fears and expose desires he’d hid for too long.

Presented in the same format across two walls, the photographs entangle each other, bodies and tree-limbs becoming fragments of the same scene. The effect is charming. Using technical lighting skills and no-fuss compositions, setting complies into subject and allows an evocative narrative to remain non-intrusive, allowing for endless possibility inside and outside of the frame.

In “Wild Place,” faces are turned away or hidden from view. The body, then, becomes a tool to discuss accumulated experience. One of the more arresting images in the show, “Smizing,” performs this emotional-accumulation best. In a gesture of exasperation, the model’s face is hidden inside the crux of their elbow and long hair covers their arms’ definition. This posture seems to roleplay emotion — sadness, specifically — rather than convey it directly with the model’s facial expression. With faces continuously hidden, the body provides more formal context, allowing postures to universalize emotional suggestions. In “Nicky, Late Afternoon” and “Last Light,” the models turn toward the natural light streaming in from outside the frame. Their postures are stable, using the support of the space around them respectively to give each image a quiet power. With faces out of view, judgements may not be easily passed by the viewer. Deliverance is somewhere in solitude, or again, some place outside the presented frame.

Together, the photographs contextualize the sexual and emotional profundity of coming out, of having that first sexual experience and then dealing with it, most likely in private, plus evoking a predisposed guilt, or shame. The choice to keep faces hidden could suggest varying levels of guilt or shame, but those feelings did not remain with me. Popular gay male portraiture often elicits shockvalue from the seemingly perverse intimacy implicit between male bodies. Rampulla forgoes this trope, choosing the emotional over the physical. In “Charles, Bay Window” (2018), a nude model is seen from behind, contemplative in his posture suggesting a moment of introspection before two windows. The model, who is bare-assed in the foreground, is not distracted by his own nudity. He is the sole participant in the scene, and will continue to be long after the viewer is gone. “Wild Place” seemed less concerned with the present rather than what would remain with its witnesses after they’ve left the gallery. I know there are many ways to capture vulnerable bodies, and I was reminded there are many ways to discover the values of hidden spaces. I was reminded of the late Alvin Baltrop, how his photographs of the bygone west side piers both avenged and memorialized a generation lost to AIDS. I also thought of the PaJaMa collective, and their idiosyncratic portraits taken on Fire Island in the ‘30s and ‘40s that serialized early queer-taste. The stories in these photographs are not mine, but somehow I am nostalgic for them.

After a long stint inside during the pandemic, I arrived at the gallery and was ushered down a flight of stairs into the gallery’s shadow space. In the basement, Rampulla and I chatted about the past six months as the photos quietly hung on the walls. When I turned my attention to them, I began to forget where I was, the photos becoming places I felt I’d seen. For a moment, I entered that strange place available to all of us. Standing before a photograph I didn’t take in a place I’d never been — familiar to my surroundings, I was lost somewhere inside of myself.

“Wild Place” is the inaugural exhibit for PROJECTION, a new initiative alongside Chart’s main gallery programming, highlighting diverse voices in intimate presentations.

On view through September 26th. Monday-Friday, by appointment. Chart, 74 Franklin St., NY, NY 10013.

All images courtesy of the artist and CHART.

Window Print, (2019).

All of the photographs in “Wild Place,” Daniel Rampulla’s first solo show in New York, do not quickly deliver their message. The differentiation of light in black and white photographs can have a chilling effect, as they do in this small, thoughtful show. Monochromatic photographs may eliminate immediate context for viewers, where color may provide a natural cache of reference. The comfort of color is not to be found in these photographs, though being hung close together helps develop a rich narrative of discovery inside of the frame. There are trees captured at night using harsh flashes; there are trees captured using daylight’s passing shadows. The trees are isolated in the frame, and when exposed, seem like unsuspecting neighbors caught naked through an opened window. Bodies are also exposed in Rampulla’s work, and these figures flank the trees. Nature, through Rampulla’s lens, is in a susceptible state.

“Wild Place” was difficult to create, he told me. It is some of Rampulla’s most intimate work to date. After a trip back home to the Bay Area, he began dredging up latent feelings of pain and fear attached to being closeted. He’d discovered himself in nature, and wanted to shed some light on that specific time in his life. By returning to familiar landscapes, like the Meat Rack on Fire Island, or the woods behind his parents’ home, he hoped to uncage himself from those adolescent fears and expose desires he’d hid for too long.

Presented in the same format across two walls, the photographs entangle each other, bodies and tree-limbs becoming fragments of the same scene. The effect is charming. Using technical lighting skills and no-fuss compositions, setting complies into subject and allows an evocative narrative to remain non-intrusive, allowing for endless possibility inside and outside of the frame.

In “Wild Place,” faces are turned away or hidden from view. The body, then, becomes a tool to discuss accumulated experience. One of the more arresting images in the show, “Smizing,” performs this emotional-accumulation best. In a gesture of exasperation, the model’s face is hidden inside the crux of their elbow and long hair covers their arms’ definition. This posture seems to roleplay emotion — sadness, specifically — rather than convey it directly with the model’s facial expression. With faces continuously hidden, the body provides more formal context, allowing postures to universalize emotional suggestions. In “Nicky, Late Afternoon” and “Last Light,” the models turn toward the natural light streaming in from outside the frame. Their postures are stable, using the support of the space around them respectively to give each image a quiet power. With faces out of view, judgements may not be easily passed by the viewer. Deliverance is somewhere in solitude, or again, some place outside the presented frame.

Together, the photographs contextualize the sexual and emotional profundity of coming out, of having that first sexual experience and then dealing with it, most likely in private, plus evoking a predisposed guilt, or shame. The choice to keep faces hidden could suggest varying levels of guilt or shame, but those feelings did not remain with me. Popular gay male portraiture often elicits shockvalue from the seemingly perverse intimacy implicit between male bodies. Rampulla forgoes this trope, choosing the emotional over the physical. In “Charles, Bay Window” (2018), a nude model is seen from behind, contemplative in his posture suggesting a moment of introspection before two windows. The model, who is bare-assed in the foreground, is not distracted by his own nudity. He is the sole participant in the scene, and will continue to be long after the viewer is gone. “Wild Place” seemed less concerned with the present rather than what would remain with its witnesses after they’ve left the gallery. I know there are many ways to capture vulnerable bodies, and I was reminded there are many ways to discover the values of hidden spaces. I was reminded of the late Alvin Baltrop, how his photographs of the bygone west side piers both avenged and memorialized a generation lost to AIDS. I also thought of the PaJaMa collective, and their idiosyncratic portraits taken on Fire Island in the ‘30s and ‘40s that serialized early queer-taste. The stories in these photographs are not mine, but somehow I am nostalgic for them.

After a long stint inside during the pandemic, I arrived at the gallery and was ushered down a flight of stairs into the gallery’s shadow space. In the basement, Rampulla and I chatted about the past six months as the photos quietly hung on the walls. When I turned my attention to them, I began to forget where I was, the photos becoming places I felt I’d seen. For a moment, I entered that strange place available to all of us. Standing before a photograph I didn’t take in a place I’d never been — familiar to my surroundings, I was lost somewhere inside of myself.

“Wild Place” is the inaugural exhibit for PROJECTION, a new initiative alongside Chart’s main gallery programming, highlighting diverse voices in intimate presentations.

On view through September 26th. Monday-Friday, by appointment. Chart, 74 Franklin St., NY, NY 10013.

All images courtesy of the artist and CHART.

1/10