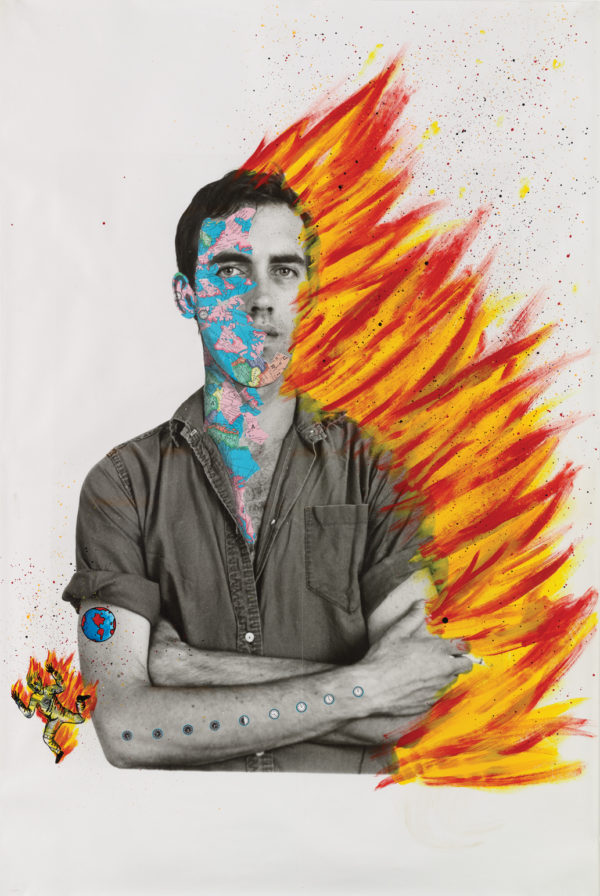

David Wojnarowicz with Tom Warren “Self-Portrait of David Wojnarowicz,” acrylic and collaged paper on gelatin silver print, 60” x 40” (1983 – 84). All images courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Estate of David Wojnarowicz.

David Dreams in Poetry

Remembering David Wojnarowicz, his search for some sort of grace, and why Everything He Made, He Made For Peter Hujar.

David Wojnarowicz had already lost so much to AIDS. But there was no bigger loss than Peter Hujar. So the day he lost Peter — November 26, 1987 — David asked their friends to leave the hospital room, to guard the door and not let the nurses in.

David got out his camera and took 23 photos, one for each pair of chromosomes in a human cell. He took a picture of Peter’s lifeless face, lips parted, eyes still wet; a picture of Peter’s open hand; a picture of Peter’s feet and toes. Like almost all of David’s photos, these 23 are black and white. We aren’t privy to Peter’s discolorations and wan skin, nor his pain and humiliation.

He wanted to offer some words in memory of his friend and mentor, his closest companion, but David — a poet prone to fiery, righteous rants — was speechless. “Nothing came from my mouth,” David wrote in his journal. “[A]ll I can do is raise my hands from my sides in helplessness and say, ‘All I want is some sort of grace.’ ”

After his own HIV diagnosis, in 1988, David would collage these photos into a painting, Untitled (Hujar Dead). Over the collage he printed a passionate paragraph condemning deathly homophobia and describing life with HIV: “I’m waking up more and more from daydreams of tipping amazonian blowdarts in ‘infected blood’ and spitting them at the exposed necklines of certain politicians or government healthcare officials.” It wouldn’t be the last time David threatened public officials.

Untitled (Hujar Dead) is one of the pieces David Kiehl, curator emeritus at the Whitney Museum of American Art, plans to feature in this summer’s Wojnarowicz (pronounced Voyna-ROW-vich) retrospective. “I think people are still scared of David,” Kiehl told me when I asked about the timeliness of the show. Kiehl contrasted him with Keith Haring, saying David’s work isn’t that kind of party. David made art to get to the bottom of something, so he deserves a serious show at a time when the public has similarly serious concerns.

When I talked with Kiehl this winter, it was obvious to me that he was taken by Wojnarowicz as a person, even if they never knew each other. I can understand; David’s work tends to have that kind of effect on people.

I first saw David’s photos in a college art textbook. Not knowing David and Peter’s story, and ignorant of the lived experience during the AIDS crisis, I read the photos like a warning. This could be you if you let too much of the world inside you, if you’re too porous, I thought. You could grow as thin as sticks. You could be dead. I added those warnings to a long list I maintained in my head: Remember the 15-passenger van that nearly ran you over because you were sissy walking with a purse. Remember your Sunday school classroom erupting in disgust and condemnation at the mere utterance of “homosexuality.” Remember your childhood best friend’s mother, her anger and confusion when she found you both naked. I carried these warnings with me, always aware of — and, in my young mind, seemingly responsible for — ways in which I didn’t belong, always searching for a place I did belong.

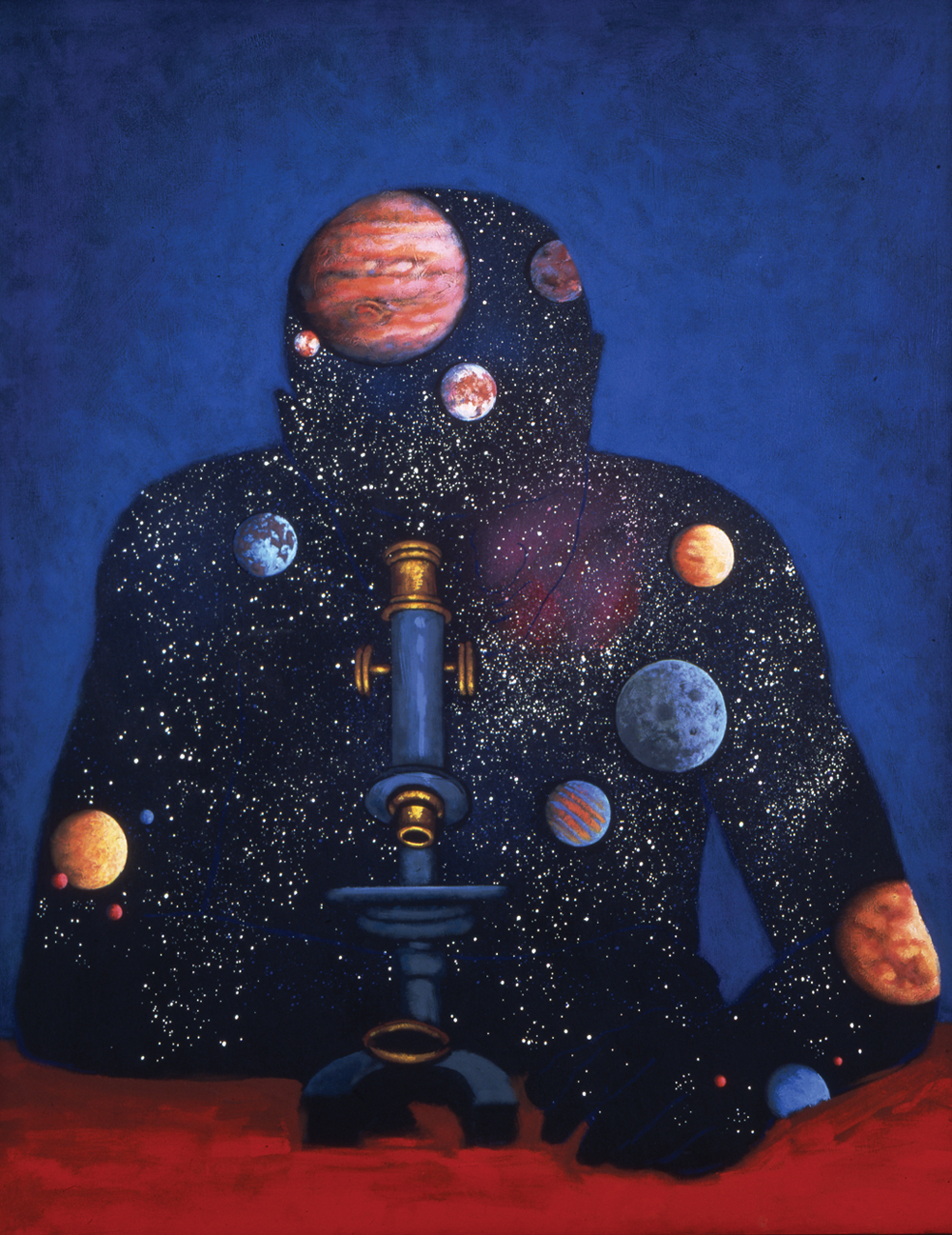

“Something from Sleep III (For Tom Rauffenbart),” acrylic on canvas, 49” x 39” (1989).

“Something from Sleep III (For Tom Rauffenbart),” acrylic on canvas, 49” x 39” (1989).

A decade later, when I first read David Wojnarowicz, I cried the subway ride home from Spring Street to 116th. With warm bodies on either side of me, someone was surely staring, but I was beyond caring.

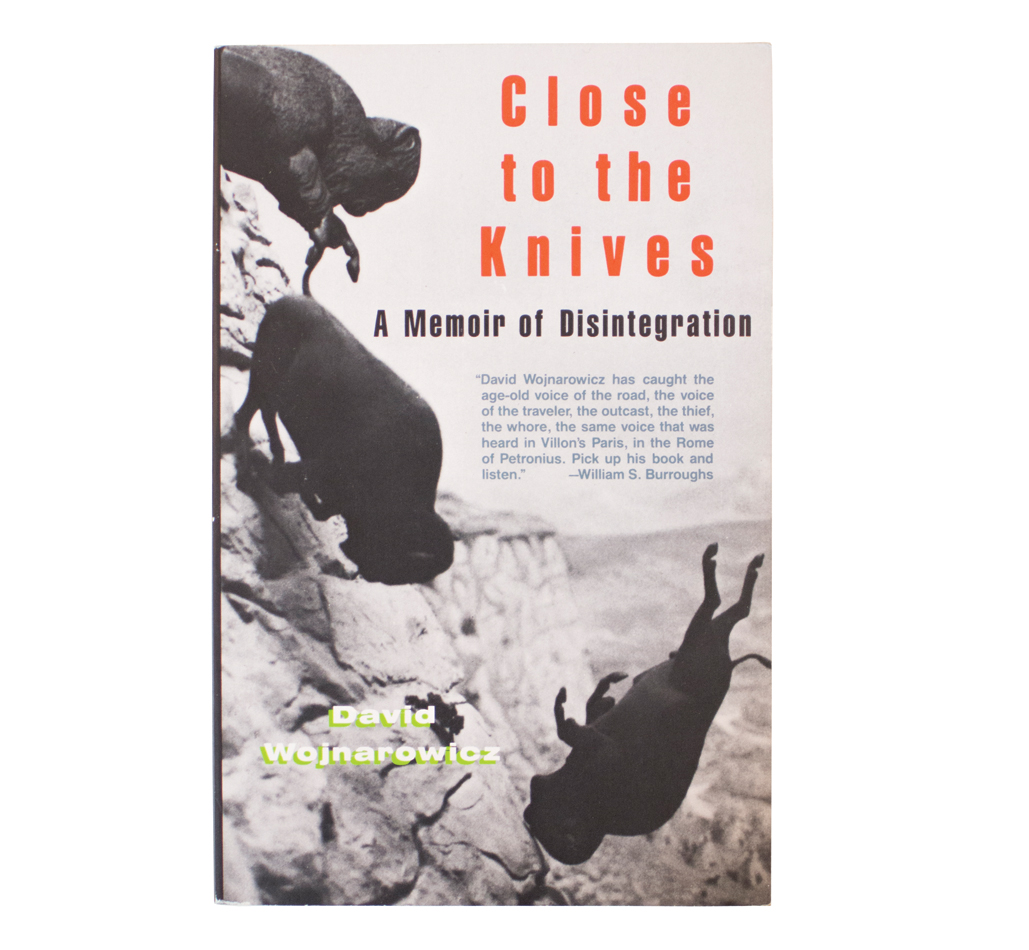

Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration begins with “So my heritage is a calculated fuck on some faraway sun-filled bed while the curtains are being sucked in and out of an open window by a passing breeze.”

I held it higher on the subway home, like a shield or a bolt of holy cloth. I wanted anyone who saw me to see the source of my emotion: David Wojnarowicz. Originally published in 1991, the book includes essays and memoir about life during the AIDS era. It hardly mentions David’s (painful, insecure) upbringing, preferring instead to focus on queers and castaways at the fringes of society. Nevertheless, David’s childhood left an indelible mark on his life and work. His father, an abusive alcoholic, was so despicable that he once fed David and his siblings their pet rabbit and told them it was lamb. He heaved a jar of pickles at David because the boy scratched an itch during one of his father’s interminable, repetitive stories. A seaman on passenger ships, he told his children they were like gulls: “All you do is eat, shit, and squawk.” They trembled when he came home, hoping he was too drunk to hit them.

Their father and mother divorced before the children had reached double digits. For years, David and his siblings had no contact with their mother. When David’s brother found her number in a phonebook, he thought she would be their salvation. Eventually, as they reacquainted themselves with their mother via letters and visits, their father became furious and dumped the kids onto her in New York City before unceremoniously vanishing. They had scant contact with their father over the next decade, though David’s older brother once pinned him to a wall and asked, “Do you realize what it is to be so fucking afraid of you? Do you know what you’ve done to your children?” Their father killed himself in 1976.

Life wasn’t kind with their mother, either. She tangled with her children until, one by one, they escaped and became estranged. David began hustling even before he left home. He turned his first trick at around 12, then spent much of his adolescence on the street, making money through sex work while learning from other vagabonds.

David was living with his sister when he got his first straight job at a Barnes & Noble and, soon after, at the Bookmasters in Times Square, now long gone. He made friends with poets, drew compulsively and dreamed of becoming a writer.

He took Bill Zavatsky’s free workshop at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project alongside Eileen Myles, another poet. “Part of the reason poetry gets sneered at as a form so often is because it’s where so many people began,” Myles told David’s biographer, Cynthia Carr. “Poetry is very often a plan. Like a list. At the beginning of a career, it can be a list of the directions you’d like to go.”

David’s poems were about lowlifes and bus station transients. The normally shy young man would get on stage in front of a crowd and erupt into a diatribe against society ills. Already he defined himself in opposition to the world around him. Whatever he might achieve, it would not be that — not the creepy, homogeneous, hetero family predisposed to anger and alcoholism.

In 1981, the first year of their friendship, Peter Hujar gave David two things: encouragement for his visual art, which changed the course of his career, and syphilis. Syphilis passed between them within days of their meeting, then cleared up with a shot. Advice passed between them while David compiled his first portfolio. He wanted to eschew his more aggressive, difficult drawings, but Peter — already a respected photographer — convinced him otherwise. David repeated Peter’s advice into a taped journal entry: “I shouldn’t start compromising and trying to adapt to other people’s taste… no matter what my taste is and what my ideas are, or what my work looks like, if it’s good, there’ll be somebody who’ll pick up on it.” David went back to his drawings and realized that, yes, there was no reason to deny them. “They’re my life.”

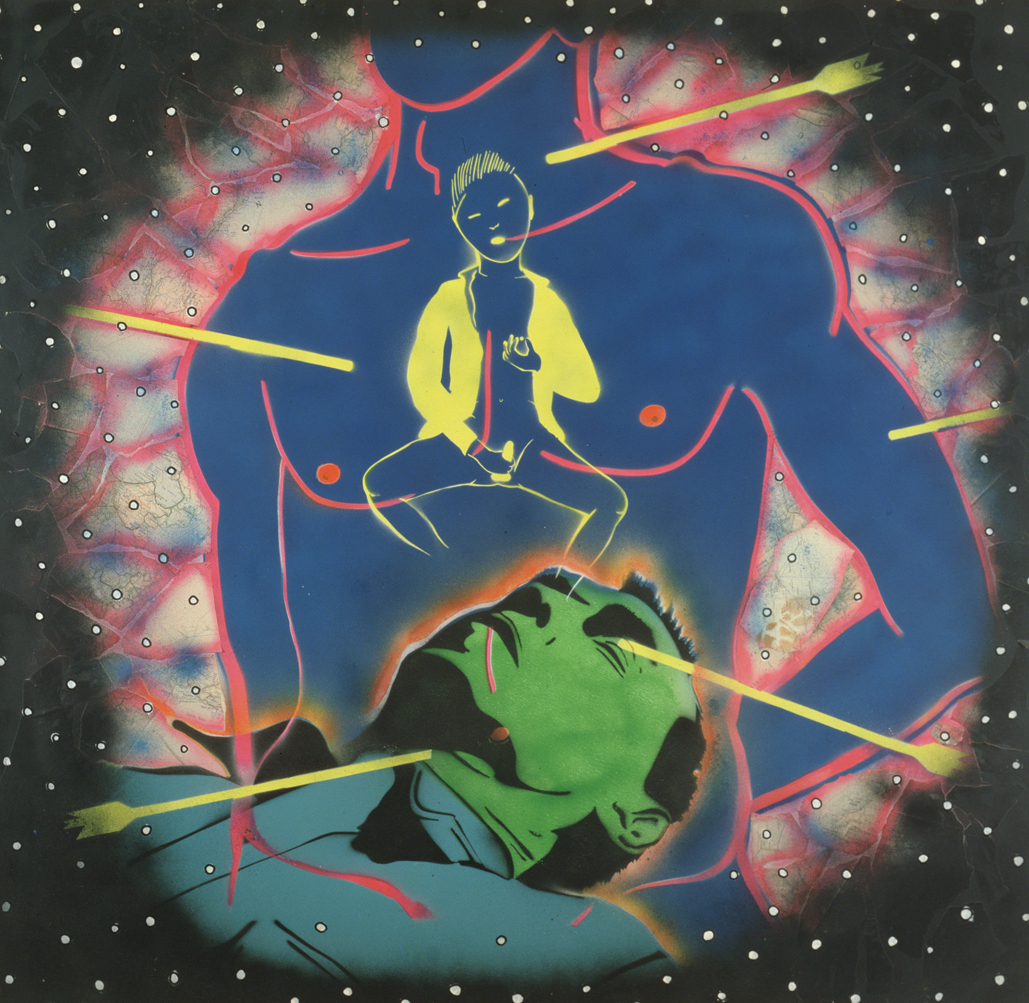

“Peter Hujar Dreaming / Yukio Mishima: Saint Sebastian,” acrylic and spray paint on masonite, 48” x 48” (1982).

“Peter Hujar Dreaming / Yukio Mishima: Saint Sebastian,” acrylic and spray paint on masonite, 48” x 48” (1982).

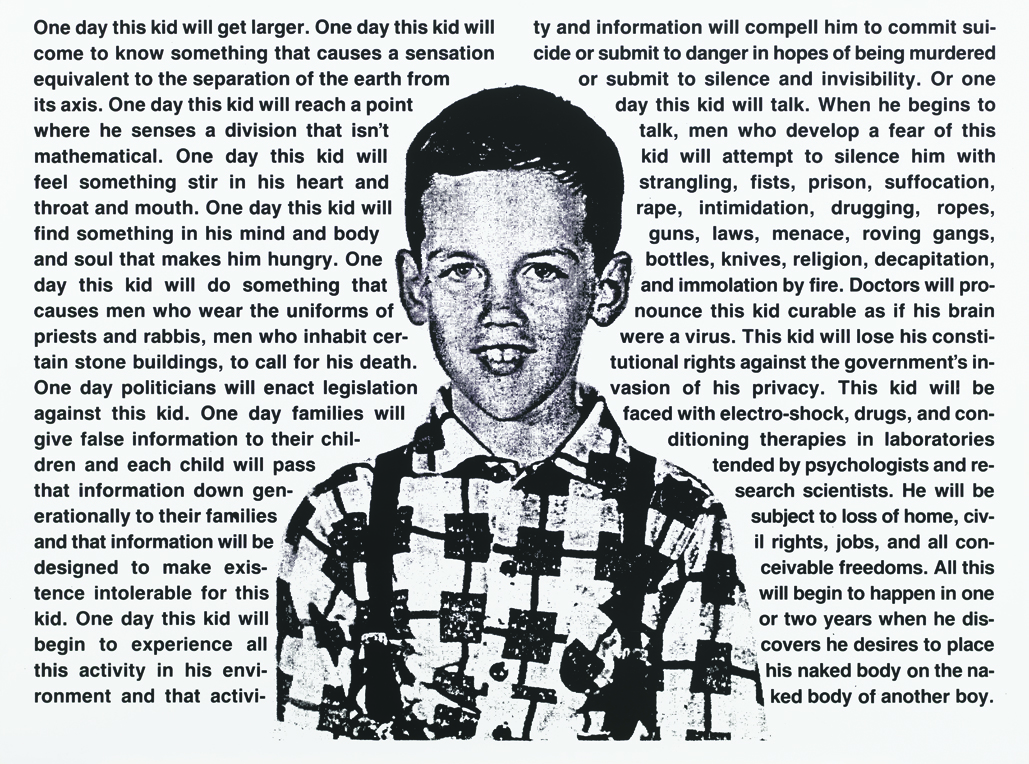

“Untitled (One day this kid…),” Photostat, 30” x 40.125” (1990). Edition of 10.

“Untitled (One day this kid…),” Photostat, 30” x 40.125” (1990). Edition of 10.

Over the next decade, Peter and David watched the raw, wild East Village art scene rise and fall. David became a principal member of a loosely aligned group of artists who wanted to break all the rules. He starred in Richard Kern short films, performed vocals and percussion for the punk band 3 Teens Kill 4, and bussed tables at Danceteria with Keith Haring, whom he loathed. The East Village scene was defined by its grittiness. Artists rented or squatted in decrepit buildings with spotty heat and water. With heroin readily available, a common street noise was dealers hawking “Works! Works!” to let potential customers know they had needles in addition to drugs. In East Village galleries of the early 1980s, one might find dog shit and trash gathered from Tompkins Square Park, live fire or smeared pigs blood. At least twice, David and fellow artists dropped acid and stayed up all night painting directly onto gallery walls.

It was in this scene that David devised the visual vocabulary found in his paintings: tornadoes, soldiers, infants attached to umbilical cords, men dreaming, homes burning, trains hurtling heedlessly into an apocalyptic tomorrow. Much of this imagery was imagined in dreams and nightmares, which David wrote down or spoke into his tape recorder.

When David traveled to Mexico, gathering material and images used in his later work, friend and fellow artist Tommy Turner recorded in his journal that David sat up suddenly in his sleep and said: “No… life as a bird. Like over a wall. A small wall of feeling. A logging ball. The fast left right. A quiet now. A quiet month.”

“Whoa,” Tommy wrote, “David dreams in poetry.”

While in Mexico, David also happened upon a rundown circus that included a monkey in a red coat riding other animals and doing somersaults, always on a leash. In his last years, Peter kept above his bed a painting David made of this monkey. The image reappeared often in David’s work as a metaphor for his idea of the “pre-invented world” or “The Universe of the Neatly Clipped Lawn.” He described this world in “Living Close to the Knives,” an essay in Close to the Knives about Peter’s last days:

the world of the stoplight, the no-smoking signs, the rental world, the split-rail fencing shielding hundreds of miles of barren wilderness from the human step. A place where by virtue of having been born centuries late one is denied access to earth or space, choice or movement. The bought-up world; the owned world. The world of coded sounds: the world of language the world of lies. The packaged world; the world of speed in metallic motion. The Other World where I’ve always felt like an alien.

Even after Peter died, David’s lovers and partners knew the primacy of his relationship with Peter. David once told Tom Rauffenbart — with whom David spent the last seven years of his life — that he had three priorities: “My work, Peter, and you. In that order.” David’s relationship with Peter was a sore spot for Tom and a source of tension between them. After David’s death, however, Tom had more perspective. “They were both more and less than lovers,” Tom said. “Peter was the one who saved him, who changed his life in a major positive way. They were kindred souls. Part of David was missing after Peter went.”

During Peter’s illness, David visited him every day, sometimes twice a day. After Peter was gone, David never stopped thinking of him. He moved into Peter’s empty East Village loft, reopened the darkroom — unused since Peter’s diagnosis — and began using it himself, prompting a shift in his artistic output. It was in Peter’s apartment that David developed all his later photographic work.

Soon, David and Tom were both diagnosed with HIV. They joined ACT UP and demonstrated with fellow members in New York and Washington, D.C. David wrote the catalog essay for Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, a 1989 exhibition of artist responses to the AIDS crisis curated by Nan Goldin for Artists Space.

“Untitled,” three gelatin silver prints, each sheet 20” x 16” and each image 10.25” x 14.69” (1988).

“Untitled,” three gelatin silver prints, each sheet 20” x 16” and each image 10.25” x 14.69” (1988).

The essay, titled “Postcards from America: X Rays from Hell,” is a furious condemnation of the institutional neglect of AIDS victims and queers in general. It names names, calling Cardinal John O’Connor — who had kept safe-sex information off local television during the crisis — a “fat cannibal from that house of walking swastikas.”

David’s excoriations helped jumpstart a national conversation about arts funding and obscenity, making David a public figure with public enemies. Before it was even published, his essay was responsible for a tense back and forth between Artists Space and the National Endowment for the Arts, putting the gallery’s $15,000 grant at risk. Around this time, in response to the NEA’s support of progressive artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano (creator of the infamous Piss Christ), a new law sought to bar the NEA from using federal funds to support such “obscene” artists. Targeted by conservative culture warriors, the NEA rightfully worried it might be dissolved if it endorsed the wrong artist.

Foreseeing trouble — and, from a legal standpoint, backing up his initial claims so as to avoid charges of libel — David expanded his essay to include “The Seven Deadly Sins Fact Sheet,” which specified what exactly made Cardinal O’Connor a cannibal. The new essay also offered evidence to support David’s claim that seven specific men could be held accountable for the deaths of thousands of people with AIDS. Among those men were conservative ideologue Sen. Jesse Helms, FDA Commissioner Frank Young and New York City Mayor Ed Koch.

One of David’s most virulent enemies was Donald Wildmon, a United Methodist minister and founder of the American Family Association. In January 1990, after David’s 10-year retrospective, Tongues of Flame, showed at Illinois State University, Wildmon sent envelopes labeled “Caution — contains extremely offensive material” to every member of Congress. Inside, under the headline “Your Tax Dollars Helped to Pay for These Works of Art,” were images Wildmon had cropped from David’s larger works. One featured the gay French writer Jean Genet done up like a saint, standing in front of an image of Christ with a needle in his arm. Wildmon, however, ignored all context and showed only the image of Christ and the needle. He also cropped images from David’s “Sex Series” and included stills of go-go boys in shiny gold shorts from David’s short film “Fear of Disclosure.” After seeing Wildmon’s mailings, President George H.W. Bush privately asked the National Endowment of the Arts if some-thing could be done about David.

A week after Wildmon sent his mailing to Congress, David got a call from the Washington Post. He told the reporter he thought those attacking him were “repressed 5-year-olds,” and the mailing did not represent his work. “They’re creating pieces of their own,” David said. “They’re not even my pieces when they’ve gotten through with them.” And Wildmon’s claim that tax dollars paid for David’s work wasn’t true. David never received an NEA grant, and Tongues of Flame was only partially funded by federal money. David had received merely a $500 speaking fee for the entire show.

It wouldn’t be the last time, in life or death, that David stirred controversy. In 2010, 18 years after he died, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery was set to open Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture, a major exhibition about the role of sexuality in portraiture. The show was set to feature David’s Fire in the Belly, a four-minute video of footage collected over the years, much of it captured as he traveled Mexico with Tommy Turner, dreaming in poetry. There are images of a mouth being sewn shut, of coins falling into a bandaged hand, of children breathing fire for tips from passersby, of a circus monkey on a leash. The Catholic League took umbrage at one segment in particular: a crucifix swarmed by ants. Incoming House Speaker John Boehner got involved, condemning the exhibit. The Smithsonian kowtowed and struck David’s work from the exhibit.

Now, of course, we read David Wojnarowicz on the subway. We cry in public over his words. We look forward to major retrospectives of his work at world-class museums.

As he prepares for this summer’s retrospective at the Whitney (July 13, 2018), curator David Kiehl says he has taken those lessons to heart. Maybe, though, despite whatever progress we imagine in ourselves and in America, not enough has truly changed since David lived and died. “I have a feeling people will take this show out of context,” the curator says.

Fifteen months after the publication of Close to the Knives, on July 22, 1992, David died of AIDS. The book is dedicated second to Tom Rauffenbart, first to Peter Hujar. As David said, “Everything I made, I made for Peter.”

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 8, get a copy here.