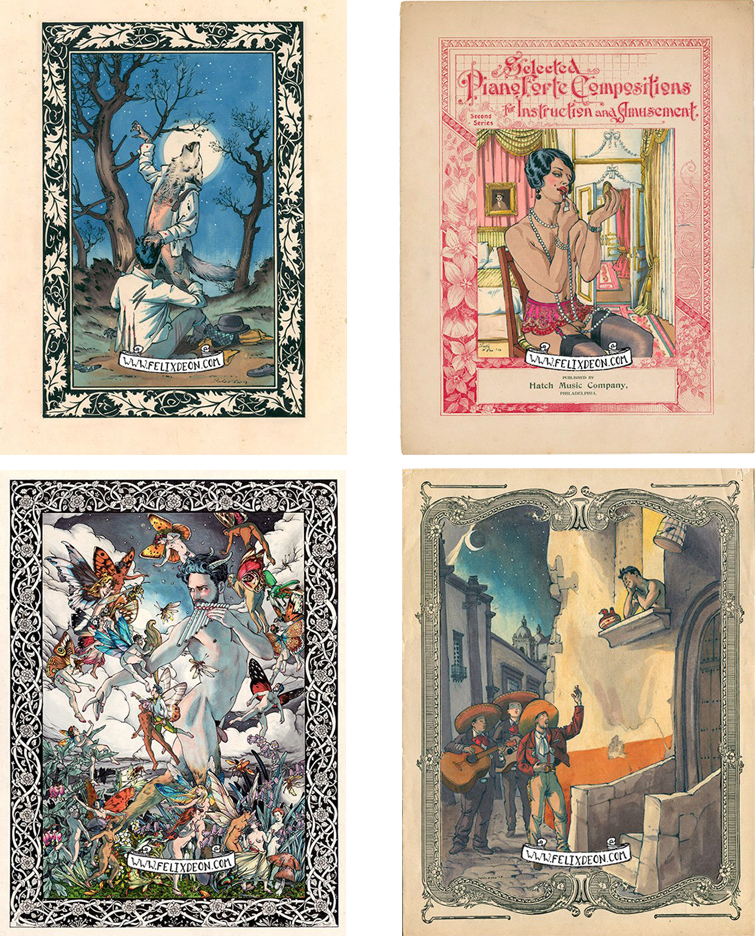

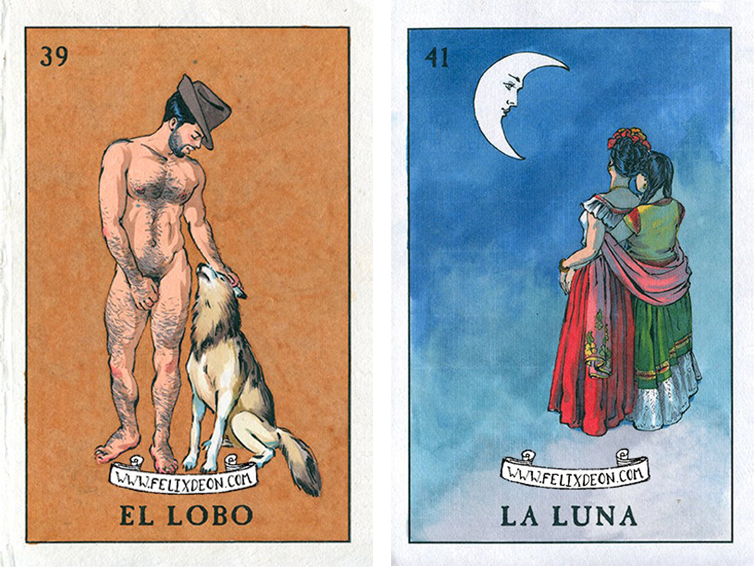

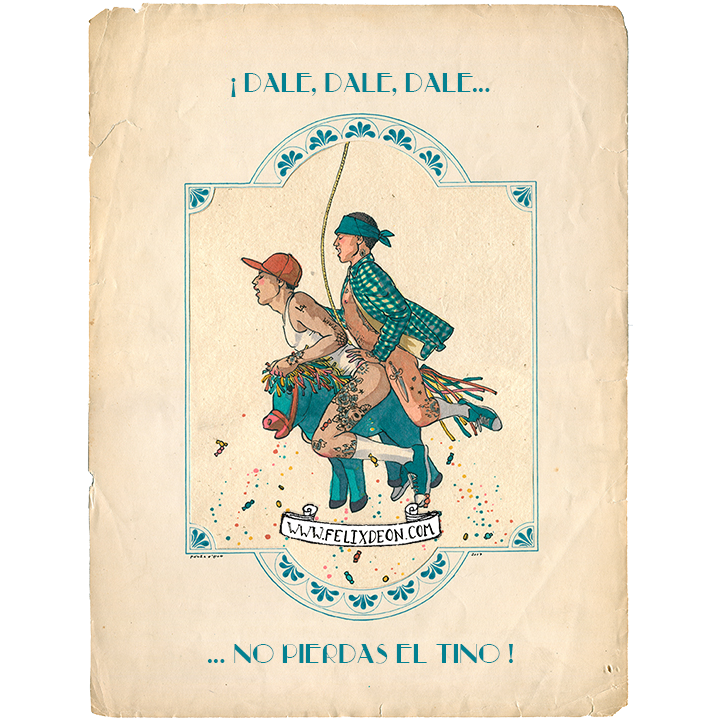

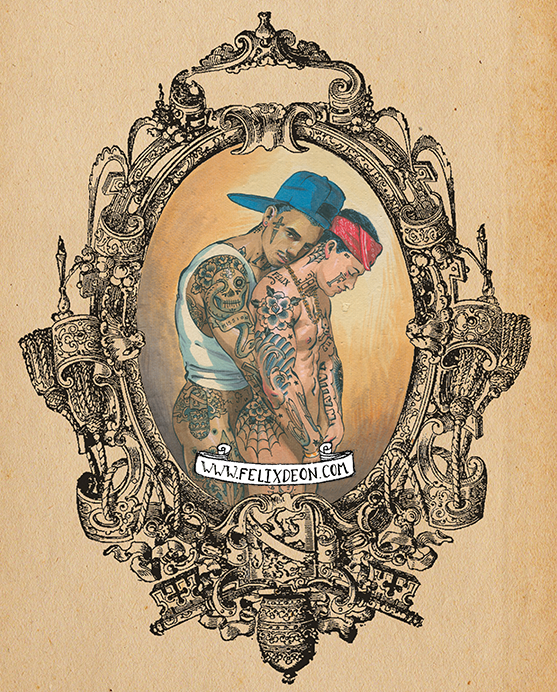

ARTWORK BY FÉLIX D'EON

AN INTERVIEW WITH FÉLIX D’EON

Modern scenes of queer love are given a nostalgic style treatment

Using politically fueled humor and nostalgia for the Edwardian era’s blurred binaries, Mexican-American artist Félix D’eon penetrates the queer landscape, uniting the past with the modern in his unmistakably potent perspective. The artist transposes seemingly chaste scenarios and interweaves sex-positive acts into a titillating statement of LGBTQ visibility. Creating a vernacular that normalizes queer desire and eradicates social stigma, D’eon’s work is innately celebratory in ethos and intention.

While in Mexico City I went to visit the ebullient artist in his studio. We spoke on influences, positive states of mind, and the importance of queer representation.

Tell us how your work differs from other queer representations. My work is almost like unsubverting queerness. My paintings have a style of a vintage children’s book illustration. There’s a wholesome feeling when you’re looking at it — whether I’m painting an old queer couple kissing in a vintage setting or a super-erotic kinky sex scene. In either case, there is a sense of wholesomeness. My work is also body-positive and sex-positive. Whereas some queer work depicts homosexuality as outlawed, my work strips sex and queer bodies of that [historical] shame.

How are you hoping to dispel stigmas of sexuality? I like to imagine a painting of mine popping up on a Facebook feed of a conservative grandma in the Mid-West and having her look at a Victorian painting of two lesbians in ball gowns giving each other a chaste kiss in the lips and realizing her homophobia is misplaced. The point is to trick you into thinking that queerness was as acceptable in the past as it is now. I want to give our history a visual reference.

What distinguishes illustration from fine art? An illustration is when someone hires me to illustrate a particular thing, so it’s a hired illustrated text. I say yes or no depending on if I like the idea of illustrating that particular thing. As a fine artist, my work looks like illustration but I’m applying the language to a different end. I’m an illustrator without a text, making stories that expand a traditional language. My intention is broader than a traditional illustrator’s intention.

When did Japanese culture begin to influence your work? My tastes are wide ranging. I love traditional concepts. My style is based on a love for the Japanese aesthetic. My Japanese friend writes poetry in Japanese on my paintings. It’s collaboration — we come up with ideas that are respectful but also funny. I’m influenced by Hokusai and Utamaro. I create my own style within that era and it ends up feeling like that era but very much my own style.

Why inflect humor into work and subject matter most artists want to serious about? I like to make artwork that is serious but I do spend half my day giggling about what I’m painting. I’m a very positive person. To be queer for most people means to suffer in some way. A lot of the queer community grow up being ashamed of themselves and it’s hard not to internalize that. My work is about making queerness hot, sexy, and funny. It’s about stripping away the pain and juxtaposing absurd social realities with humor.

As an artist working through queer forms, why focus most heavily on trans-representation? My work is about inclusivity. When I travelled to California, I searched for trans models. I wanted to find out how they wanted to be represented. In doing that, I’ve made many trans friends who have educated me about their realities. It’s important that my work speaks to the trans community. I want to make paintings that represent the queer community as a whole. It’s about acceptance, love, and being open minded. People send me letters saying they feel like they’re being represented in a way that they may not be used to seeing themselves represented.