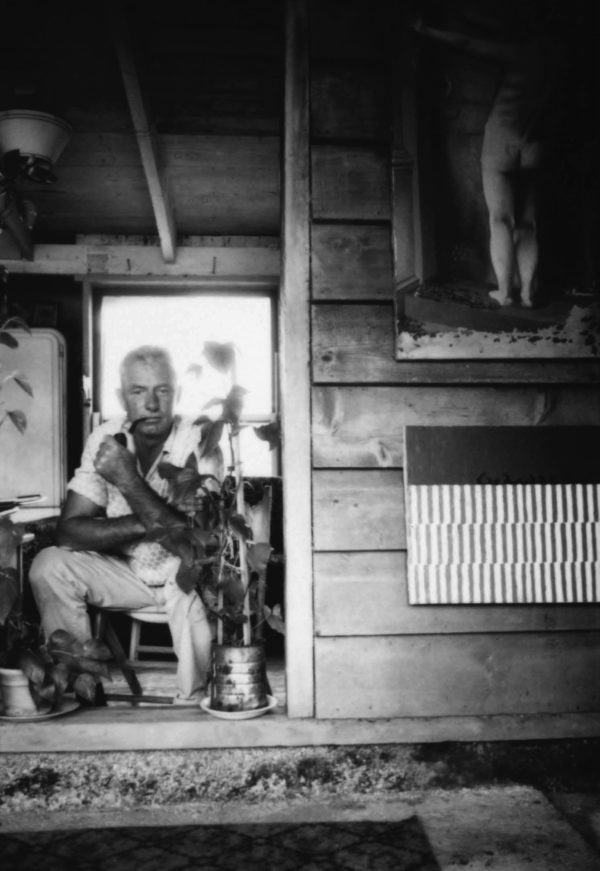

Portrait of Forrest Bess by Eve Arnold, 1958. ©Eve Arnold/Magnum Photos. Courtesy of Menil Archives, The Menil Collection Houston.

Forrest Bess

Before ‘gay visibility’ if a person discovered same-sex attraction within their heart but was not wealthy and privileged enough to construct underground networks to live comfortably in an alternate lifestyle, for some, the only answer was to seek meaning in life through esoteric study. In global cultures, comparative anthropology, non-western religions, and erotic mysticisms, one could inhabit an identity nobler than ‘local cocksucker.’ Who wouldn’t rather be a Uranian, a sexual invert, or follower of Ganymede than a mere homosexual stuck in a hetero-normative culture?

Forrest Bess lived in a shack on the gulf of Mexico, not far from Houston, Texas. He woke before dawn each morning to sell bait to local fishermen. He led an isolated life, painting his ‘visions’ in oil on small canvases and maintaining a distant but steady correspondence with sympathetic fellow travelers in New York and elsewhere. In time, Bess would meet prominent gallerist Betty Parsons, gain popularity as a pure abstract painter, and become an art world legend, his paintings revered as objects of desire.

Texas is quite unlike the rest of the United States. Physically bigger than most countries in Europe, many residents understand their state to be another country. Texas’ libertarian ideology allows for a greater personal eccentricity to be socially and institutionally supported in ways that are rare in the highly controlled worlds of Boston, Washington DC, and New York. Houston only became a major city after 1900, when a hurricane wiped out the bigger city of Galveston. The city then grew quickly after the lucrative commodity of oil and natural gas were found in abundance. The first oil barons were uneducated and cared little for the arts. Soon though, their kids, able to afford Harvard and Yale returned, often with wives raised in the East who would not stay in Texas unless the museums, ballet, opera and French restaurants were of the highest quality. The oil money created jobs, and the culture created new freedoms, and for most of the first half of the 20th century, Houston and New Orleans were the only places one could have a gay life in the South. So those who could move to Houston, did.

Bess was born in a working class family and attended college for architecture in Austin and San Antonio. He studied little but spent most of his time reading in their well-stocked libraries. During World War II, he enlisted in the Army, designing camouflage and eventually teaching bricklaying. He had a natural ability to paint and quickly started working in a derivative but accomplished Texas version of a late impressionist Parisian style. Some of his realist paintings from this time in his life are evidence of great skill. A few collectors own these earlier still lifes and figurative paintings, perhaps in an effort to map out his road to more abstract forms and subjects, much in the way Modernist historians treat the oeuvre of other painters including Norman Lewis, Agnes Martin, and Jackson Pollock. One collector of Texas art discovered a wildly homoerotic self-portrait of the young artist in a posing strap, while intriguing, it only tangentially relates to the reason the cult of Bess among today’s art makers and collectors keeps growing.

Untitled (Pink Moon), n.d.

Untitled (Pink Moon), n.d.

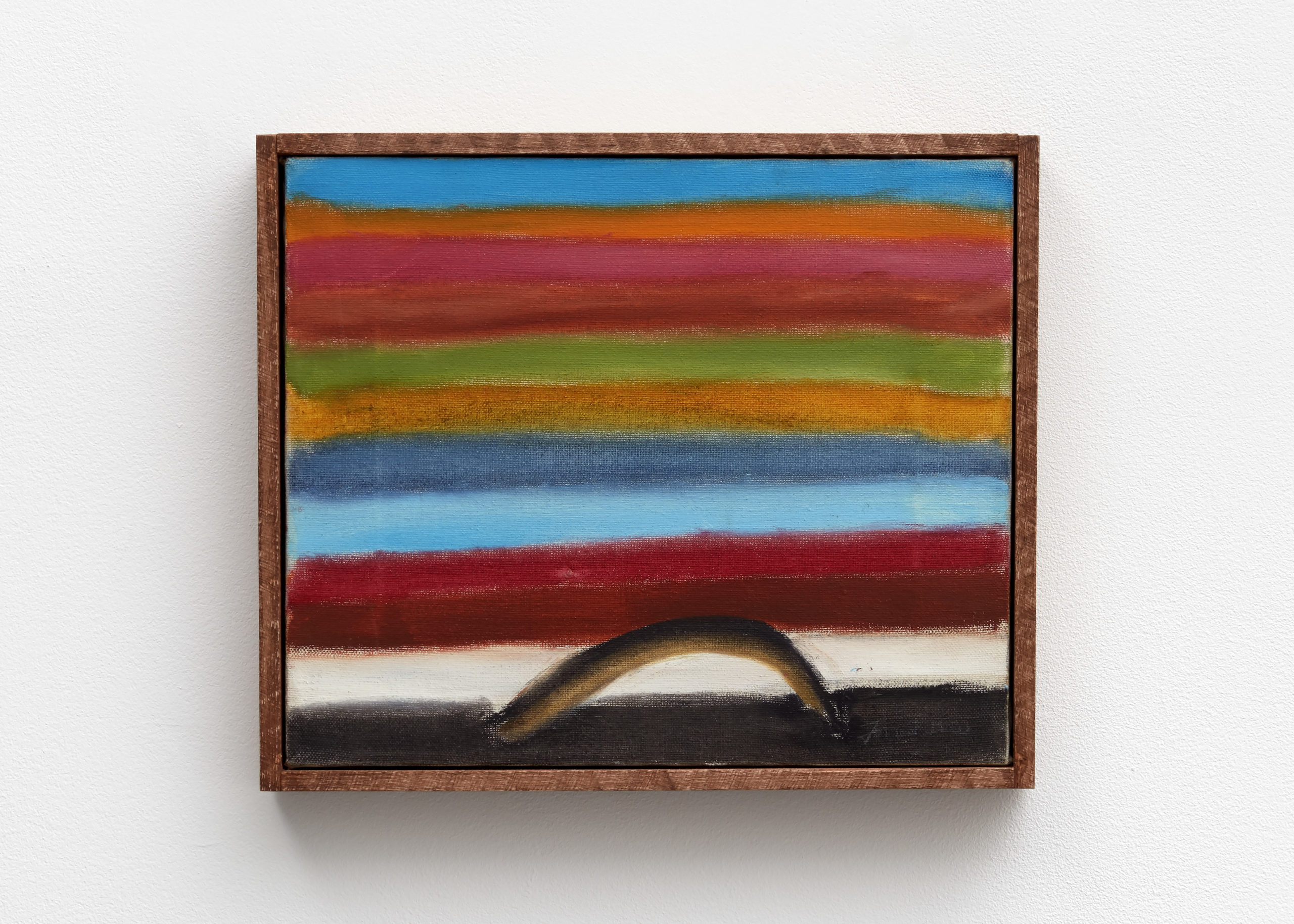

Untitled (Rainbow with Arc), n.d.

Untitled (Rainbow with Arc), n.d.

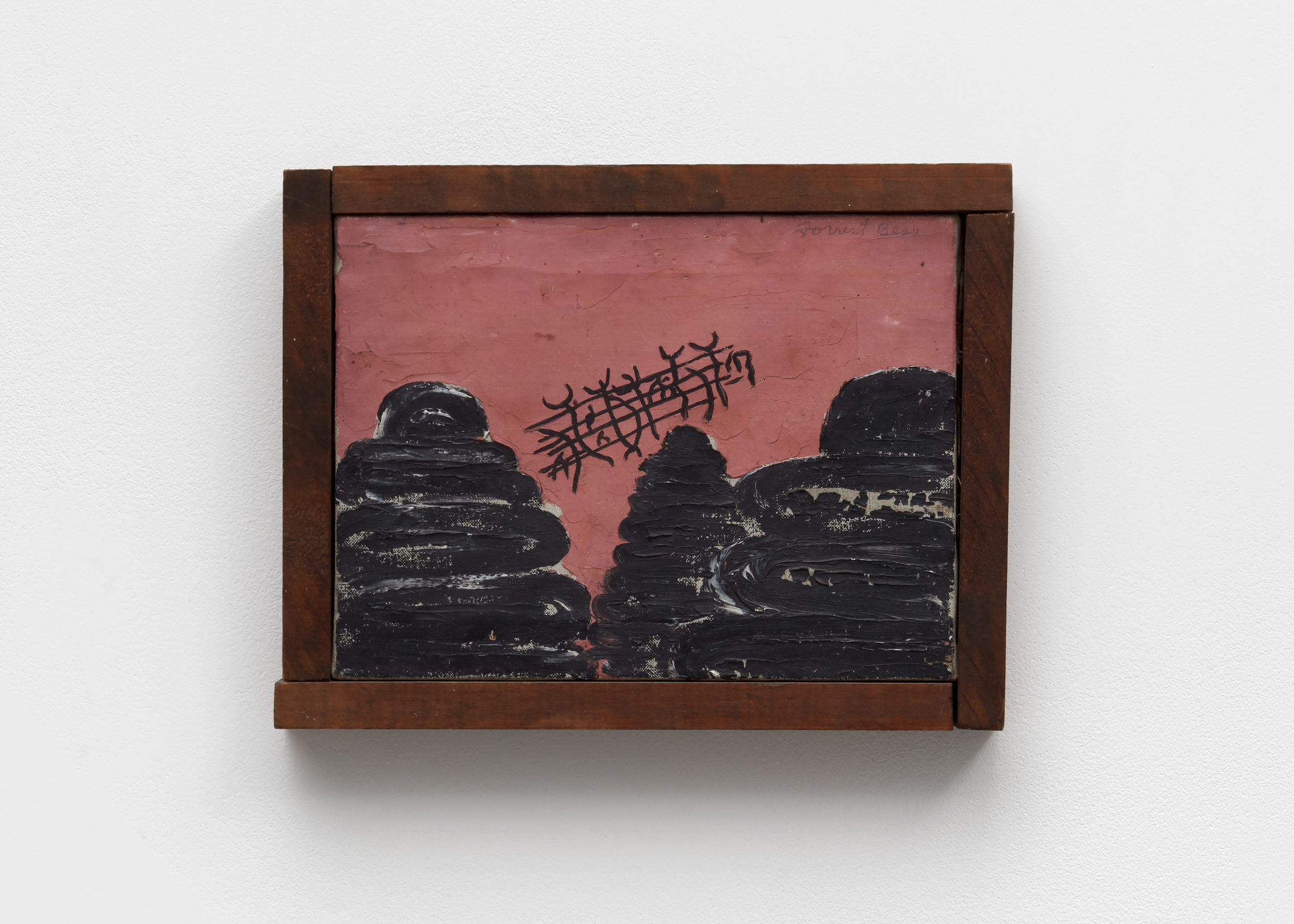

Untitled (No. 18), 1952.

Untitled (No. 18), 1952.

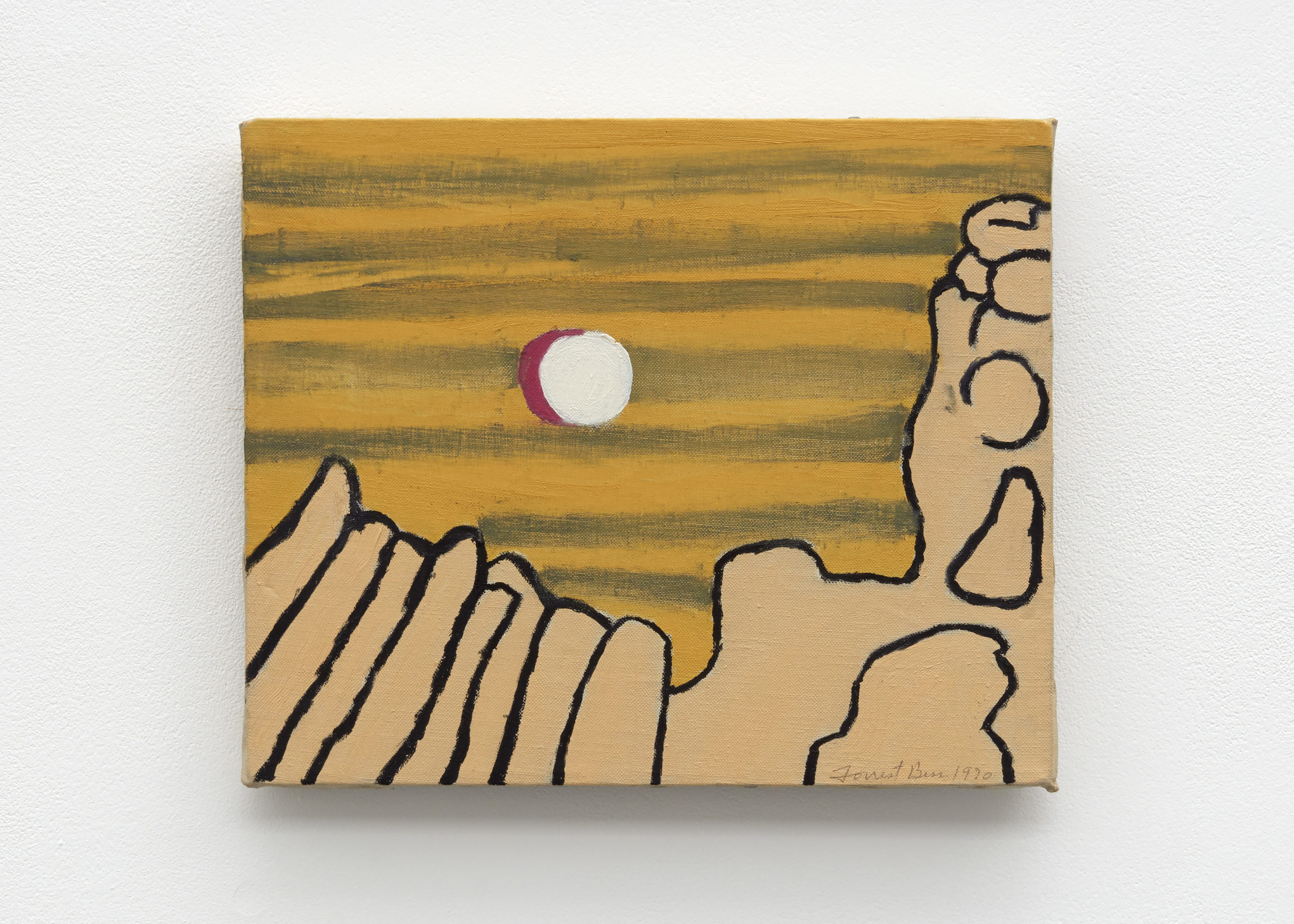

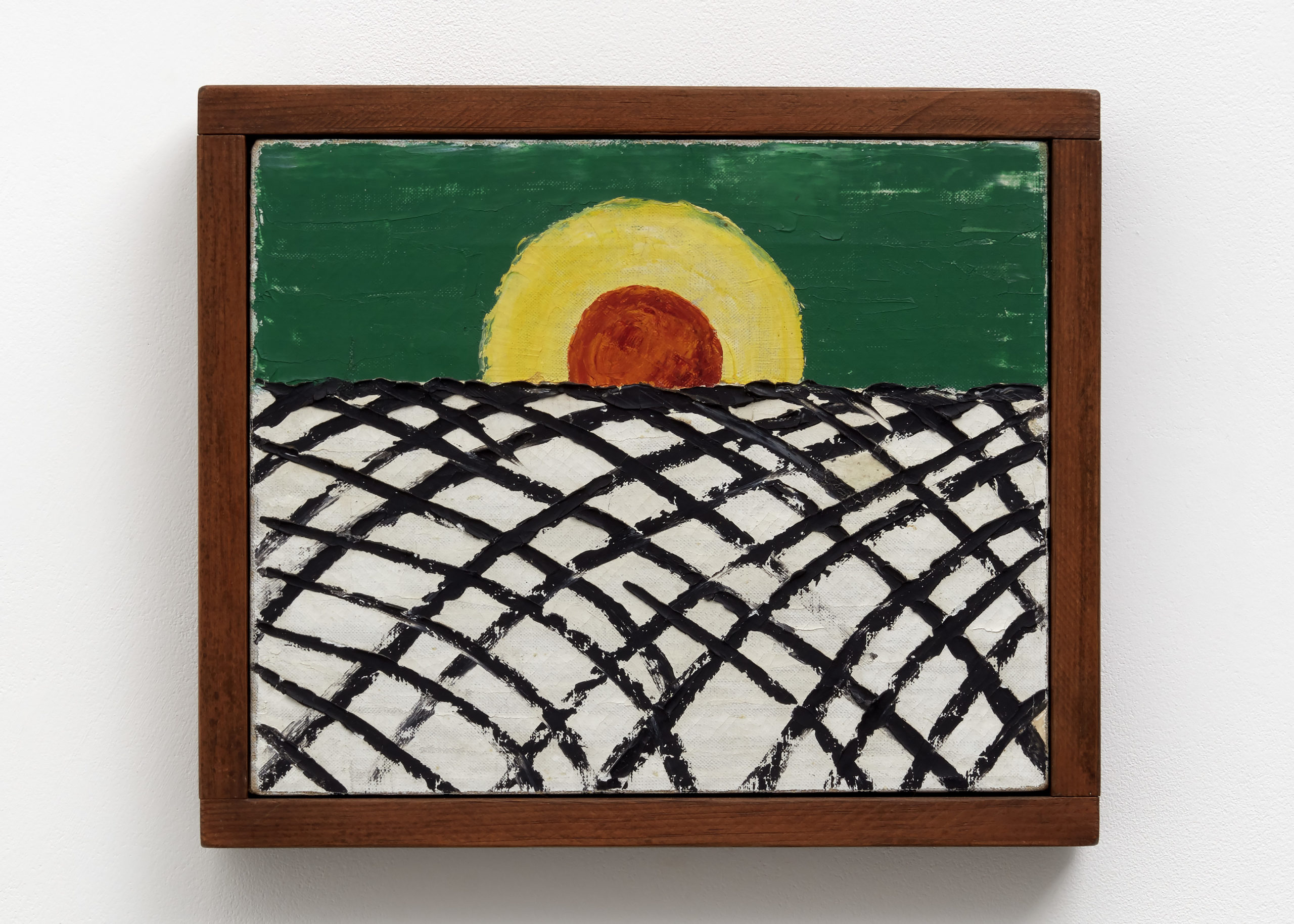

Untitled, 1970.

Untitled, 1970.

Untitled (No. 10), 1957.

Untitled (No. 10), 1957.

Untitled, 1948.

Untitled, 1948.

He described himself as a “peculiar type of homosexual.” In his small town life he understood himself to be “the peculiar one,” and moving to Houston and involving himself in its larger arts community, even mounting a solo show at the Contemporary Arts Association in 1962, proved no better. In his perception, he describes himself as “too butch or rough” for the other gays he found. Still, he was clearly getting laid at points, as he complains about dry periods when sex was not possible. In a letter to straight friends, he states matter-of-factly, “I do not think I can repress the sexual urge. The alternative is to blow my brains out and I am not in the mood for this.”

During the war, he made a move on a fellow recruit when drunk and the man tried to kill him, cracking his scull and putting him into a coma. After that he started having visions in his sleep, and he would note the symbols he saw and when awake he would paint them. He became convinced that these symbols were being revealed to him not invented by him and would endeavor to paint them as directly as possible. The result was a type of unartful paint handling that remains inspiring to a diverse group of art makers. Today, It’s Bess’s visionary paintings that museums and galleries clamor to show or own. In a provocative statement, he stated in a letter to Parsons he never considered himself an artist but mere a conduit inspired by “the evil Of Dionysus.”

Bess’s lifelong investigation into masculine and feminine archetypes of particular world cultures led him to the study of male initiation ceremonies. As his obsession mounted, he endeavored to perform a surgery on his own genitals known as a ‘sub-incision’ with only booze for anesthesia. He created an opening at the indentation under the root of his penis, above the testicles. Bess considered this as a vestigial vagina and other studies convinced him if he could receive semen in the newly opened orifice, the aging process would reverse itself, and he could become immortal. He explains the surgery was his attempt to live in this hidden truth, “all symbolism in art points toward this mutilation as being the basic step toward the state of the pseudo-hermaphrodite as the desirable and intended state of man.” He documented both the opening and his naked body in scientific exactitude, photographed against a mechanical grid for the sake of measuring his future muscle growth. When the opening was made, he stated, “The unconscious flooded in beautifully. I had found entrance to the world within myself.”

Bess’ theories around sexuality, which he described as his “thesis” in numerous letters during the course of his career, were central to his art making practice, and he wanted his writings displayed alongside his paintings. Betty Parsons, his dealer, was an out lesbian, and a tough critic. She represented the most recognized artists of the period and was sympathetic to Bess’ exotic queer loner life, but politely declined to show his work. She feared the paintings would be seen as mere illustrations. Eventually she showed the paintings at her New York gallery regularly between 1949 and 1967.

“I was moved from Oil boom town to oil boom town – mud tents, rain barrels, struggle – but hidden From everyone were my secret desires and loves. Fantasy. The cat with eyes as big as mill wheels and my love for the ginger bread man and the smell of a box of watercolors.”

From Bess’ letter to his gallerist Betty Parsons, November 1949, quoted from Forrest Bess’ Key to the Riddle.

In art historical practices, the over-emphasis of an artist’s biography is derided as a type of romantic laziness, but in Bess’ case, it is hard to resist. The idea of Bess as an “outsider artist,” a maker of memorable objects, who was, for reasons of mental illness or imprisonment, are unable to participate in the dominant art world, is untrue. Bess was possessed by esoteric visions, living in a shack at the end of the world, but he knew what the art world was and wanted his place at the table.

One of the great generation of post-war art historians, Meyer Shapiro, admired Bess and kept in regular communication with him, even helping when the artist ended up in a mental hospital after repeatedly wandering naked through the streets of Bay City, Texas. The doctors were disbelieving when he claimed he was a famous artist, and Shapiro graciously wrote to correct them.

Bess’ complete “thesis” is lost, but Robert Gober, the great American artist and ultimate Bess-obsessive was able to make Bess’s dreams come true posthumously in approximate form at the Whitney Museum in New York by contributing to the Biennial a display of Bess’ works shown with the documentation of his surgeries. The Menil Collection owns a sizable amount of Bess’ best paintings, and showed them in a 2013 exhibition which also featured writings of his body modification.

The mystery of his symbol system is often the first way viewers try to untangle Bess’s arts’ magic but strict decoding will not end in translation. Bess never created a coherent system but, rather, was decoding images that appeared to him, appearing as someone guessing both why such images haunted him and how they might in fact be timeless manifestations of some original truth. No less a figure than Carl Jung wrote him back and assured him his visions had significance. Poet, painter and essayist Wayne Koestenbaum, who has made paintings in dialog with Bess’s best works considered him thusly:

“Bess’s best paintings contain heavy iconographic messages—worship me! fuck me!—but wrap these messages in imagery so elemental, so primary, so unelaborated (circle, line, wiggle, star, triangle) or in colors so unmodulated (a gray that remains gray, that heads toward the nongray but never makes much progress in that direction), that the iconography’s simplicity may fill the viewer with a sense that any language’s attempt to communicate is doomed to fail.”

My 1980s and Other Essays by Wayne Koestenbaum.

Here is a Sign, 1970.

Here is a Sign, 1970.

Untitled, 1957.

Untitled, 1957.

Rain of Colors (No. 3), 1970.

Rain of Colors (No. 3), 1970.

Untitled (No. 6), 1957.

Untitled (No. 6), 1957.

Mandala, 1955.

Mandala, 1955.

Old Boats, 1967.

Old Boats, 1967.

Untitled (No. 7), 1957.

Untitled (No. 7), 1957.

Untitled, n.d.

Untitled, n.d.

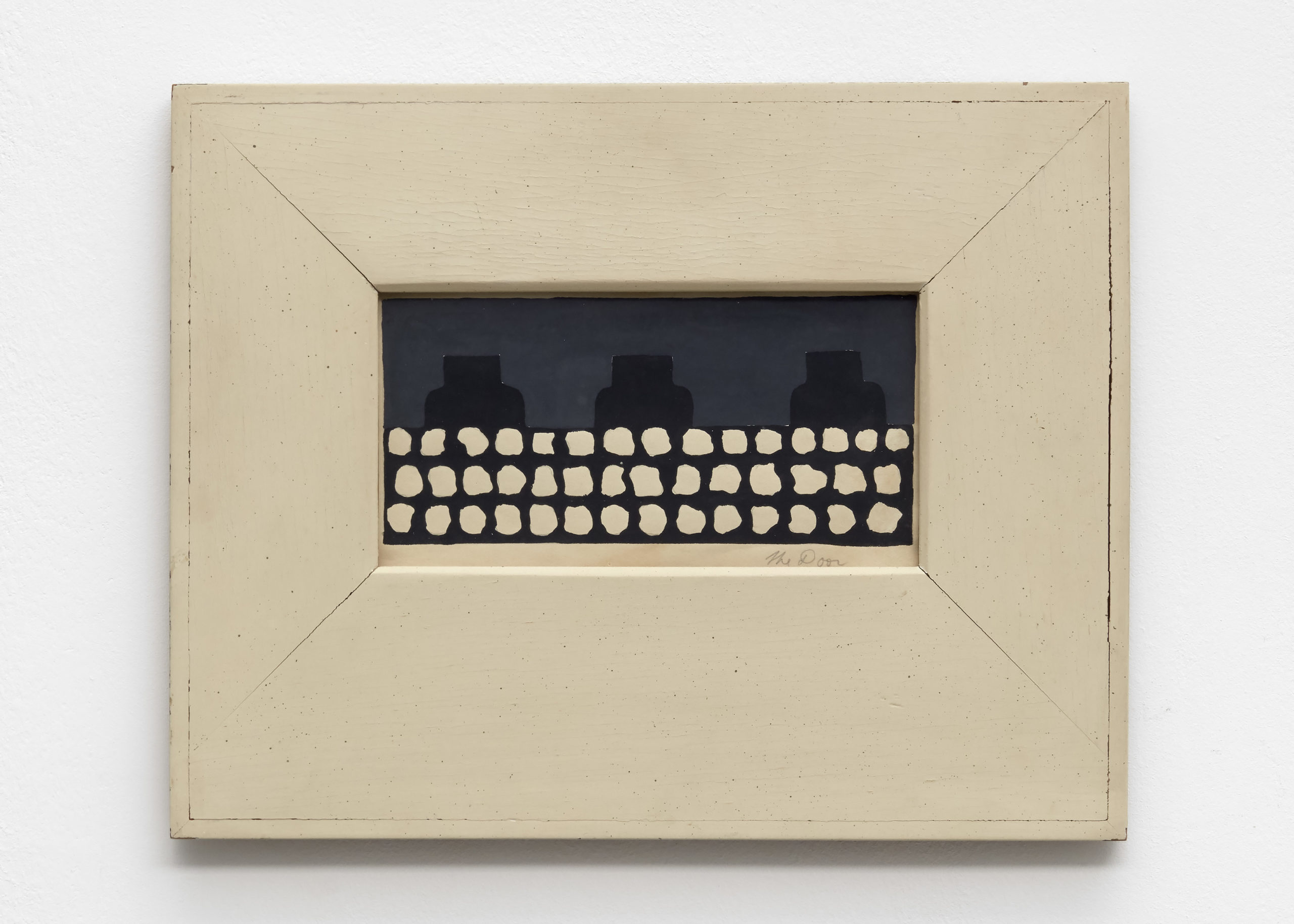

The Door, 1959.

The Door, 1959.

When Bess’ studio was destroyed in Hurricane Carla in 1961, he announced his intention to commit suicide by drinking. In the best of circumstances that is a slow process, and he lived until 1977, during which his troubles mounted. We know from his writing he was often lonely and hoped to find others who would understand. He wrote longingly of an image of two men almost touching walking along a lonely road in a Van Gogh painting.

But there are reasons to believe he was often surrounded by intriguing people who cared for him and were willing to help. Bay City was a small city but there was a socially prominent gay couple who took care of him, Harry Burkhart and Jim Wilford. Burkhart was a scion of a ranching family and his companion owned the socialite ladies hair salon, Stylez Inc. After Bess’s death and the Whitney Museum’s first museum show outside of Texas after his death, the hunt was on for sellable Bess paintings, and there are stories, mainly apocryphal, of prominent dealers rummaging through Bay City junk shops and even the city dumps of hoping to find lost paintings. Bess did give them to friends and neighbors who had no way of knowing the abstractions would soon be very valuable, Burkhart and Wilford owned over 40 which are being slowly sold off to benefit the Houston hospital that took good care of Wilford as he was dying.

This complicates that idea of Bess a total loner. According to Houston painter Terrell James who worked with the Archives of American Art to preserve and make accessible as much of Bess’s life and writing as possible, Burkhart was out, wildly fun even in his elderly years. He was an active supporter of the arts in Bay City and Bess, the world-renowned painter who lived in Bay City and made them proud. They bonded and frequently ate with Bess.

Bess’s explorations of gender and spirituality makes him irresistible from the perspective of 2020, but what his life and art tell us about negotiating the world as a gay man in regional America is breathtaking in its audacity. Thinking of gay life in 50s and 60s small town Texas and realizing that Bess managed a prominent career from a small shack shows what is was possible. It tells us more about the spaces gay men could make for themselves in Texas, not despite but because of the state’s respect for individualism. No doubt Bess’ work will continue to charm and mystify its viewers, and his life story stands as a chapter in queer art history.

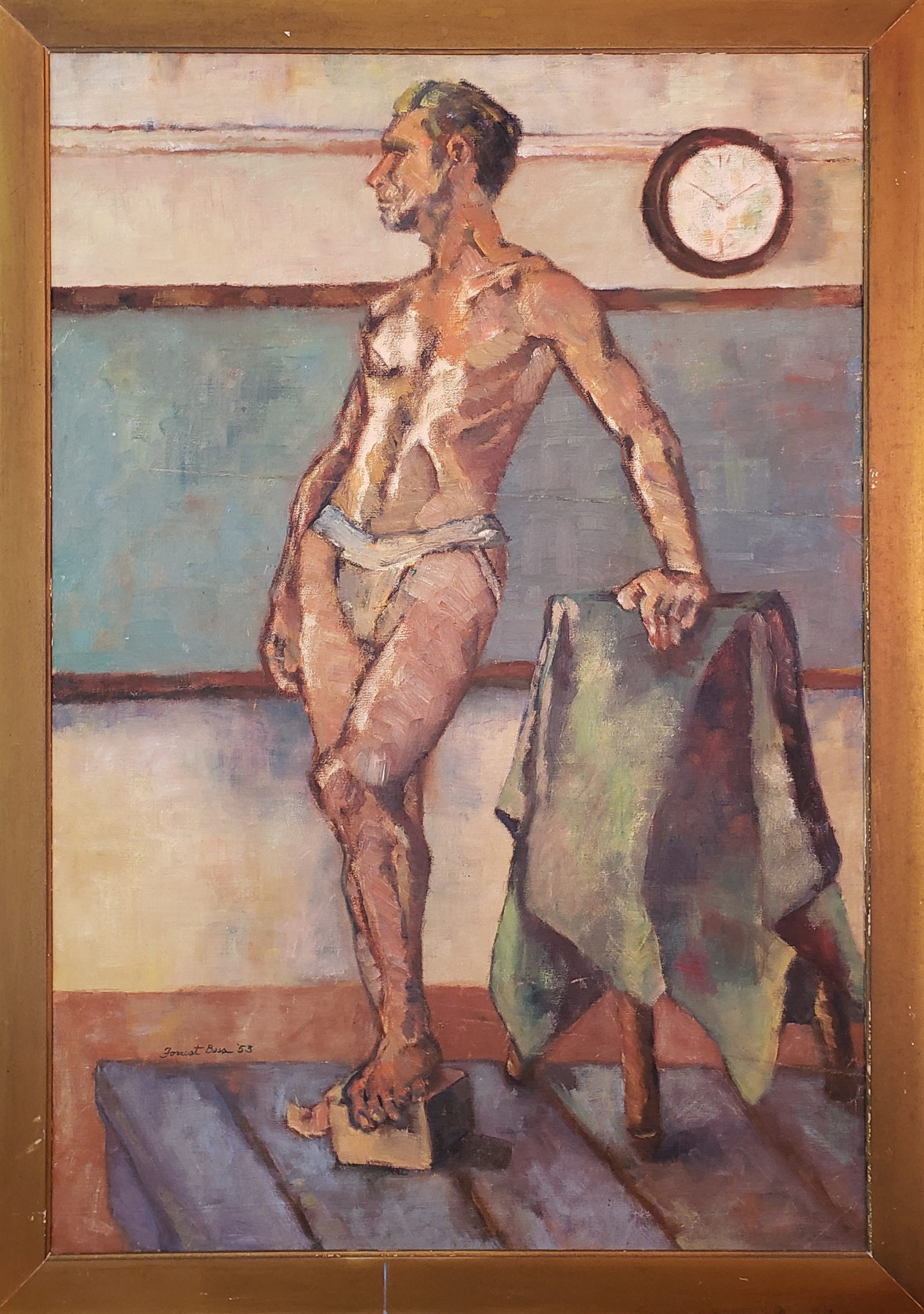

Untitled, 1953, image courtesy of Collection Randy Tibbits, Houston, TX.

Untitled, 1953, image courtesy of Collection Randy Tibbits, Houston, TX.

All artwork courtesy of Modern Art Ltd.