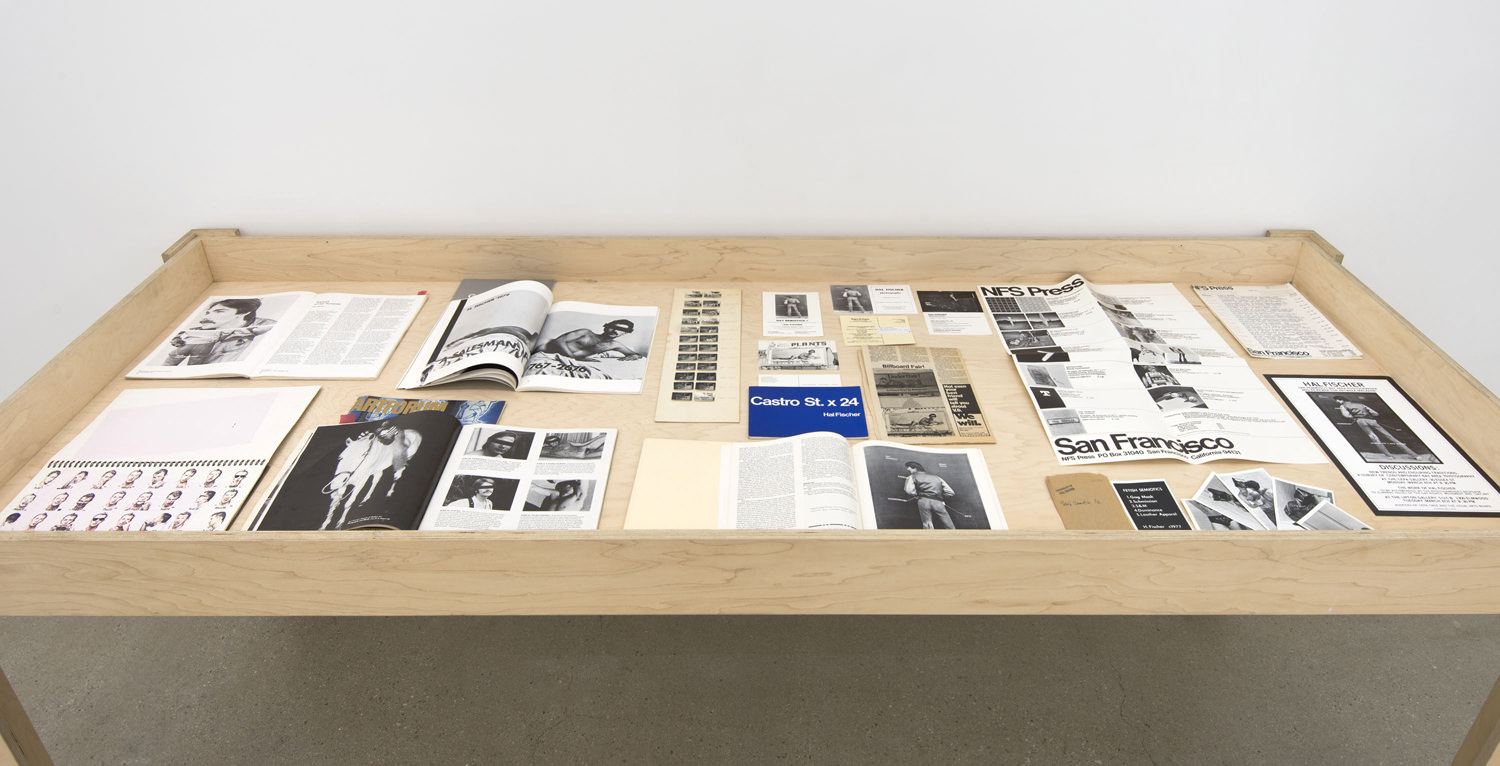

Images Courtesy of Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles. Photo credit: Brian Forrest

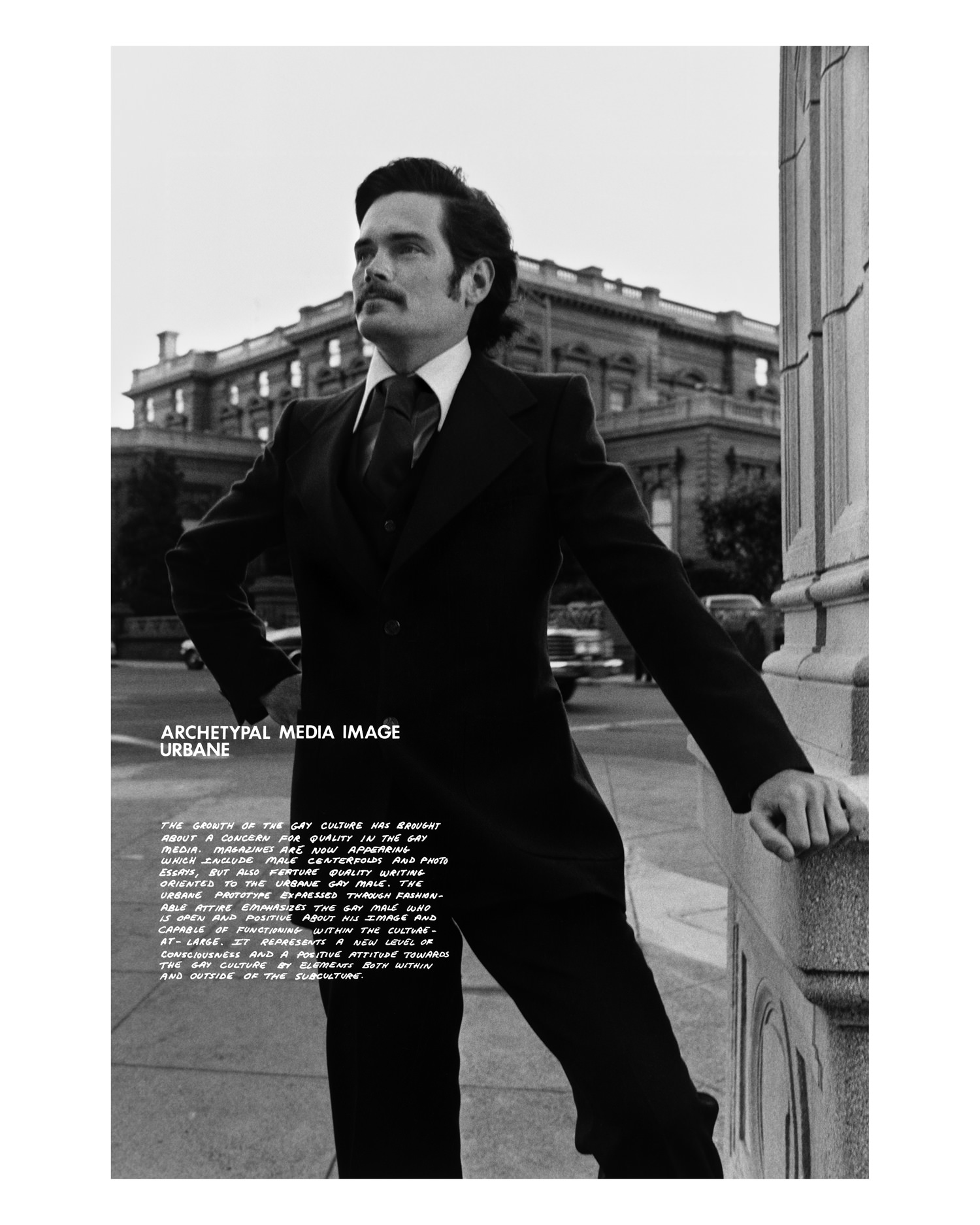

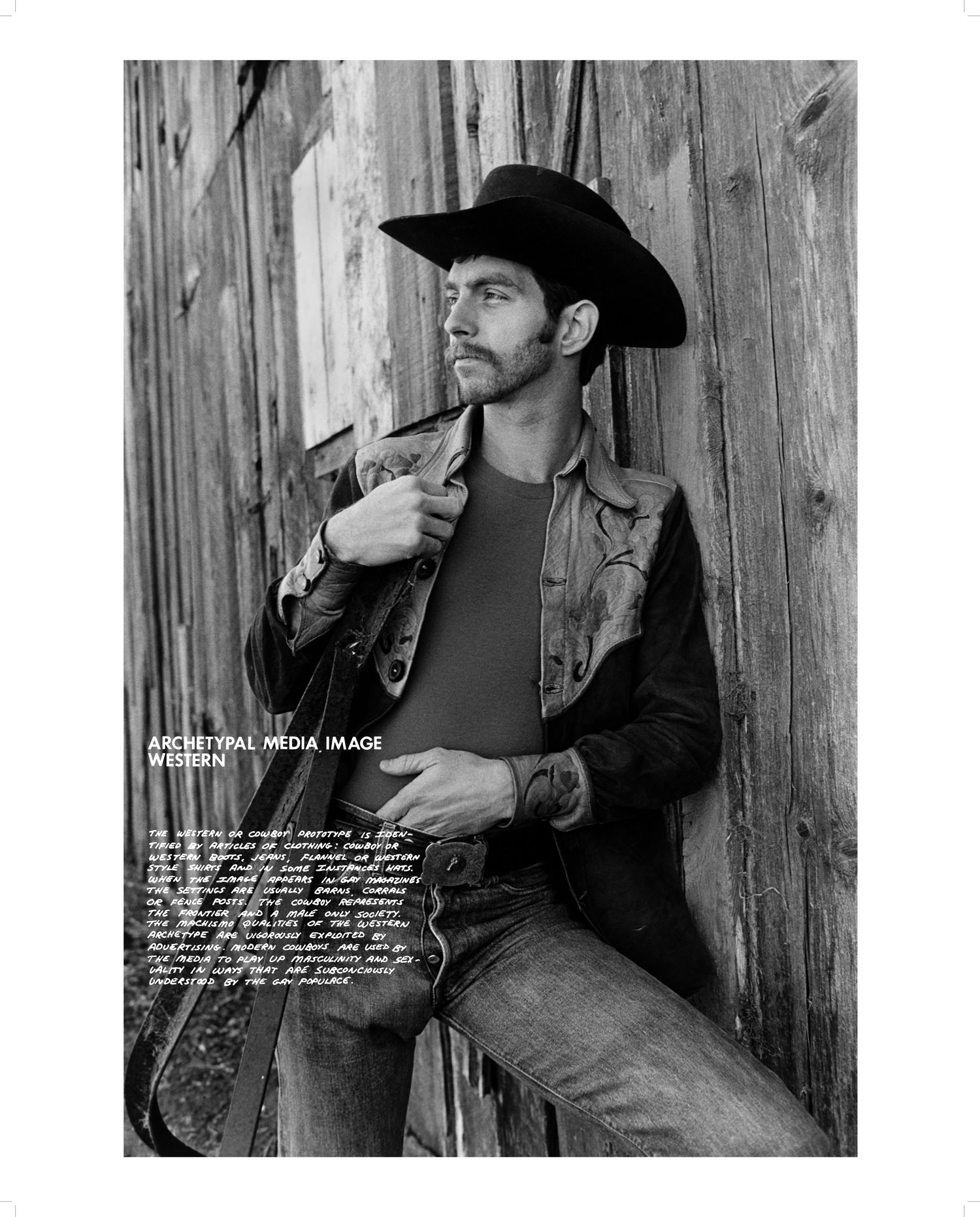

Hal Fischer’s Gay Semiotics

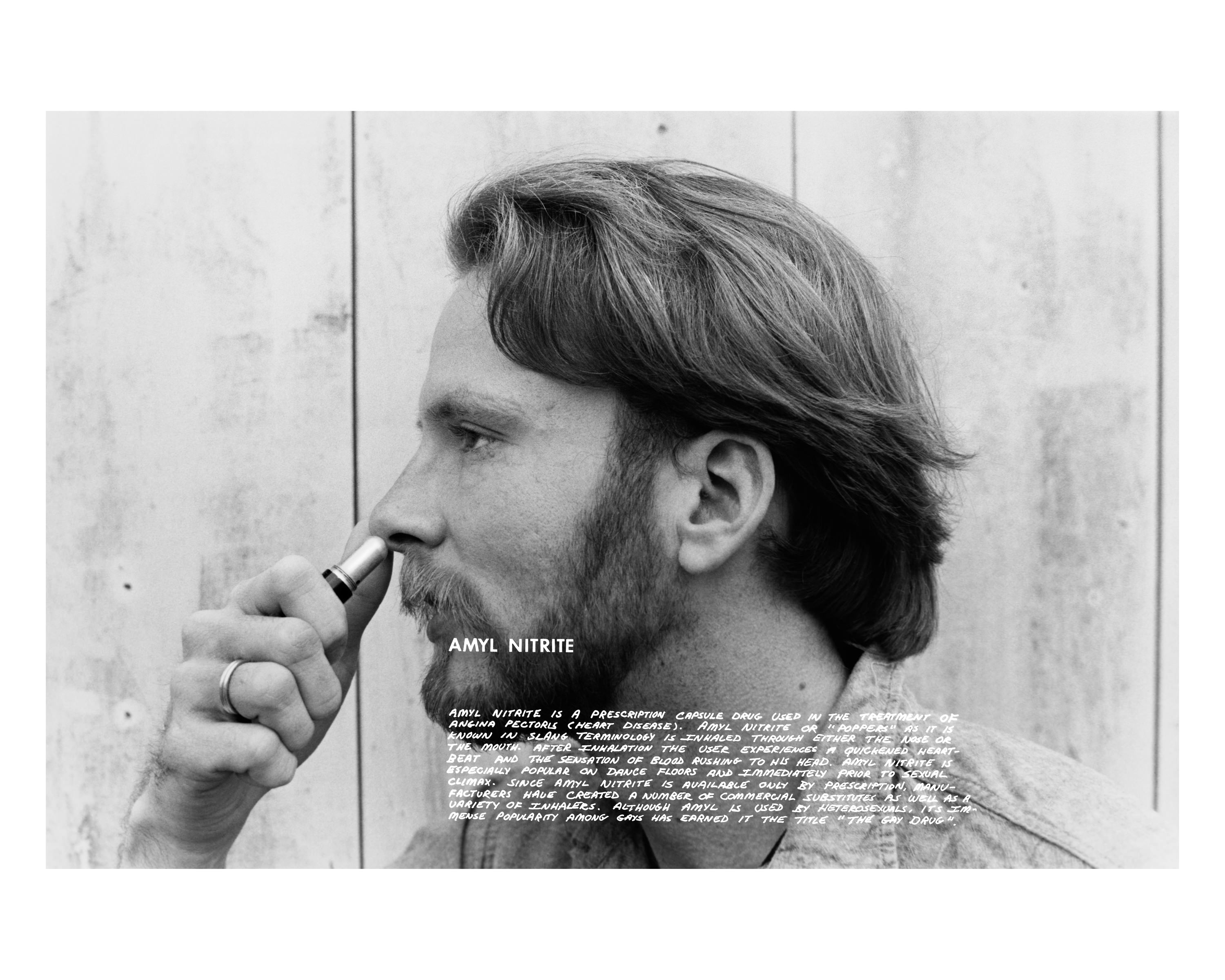

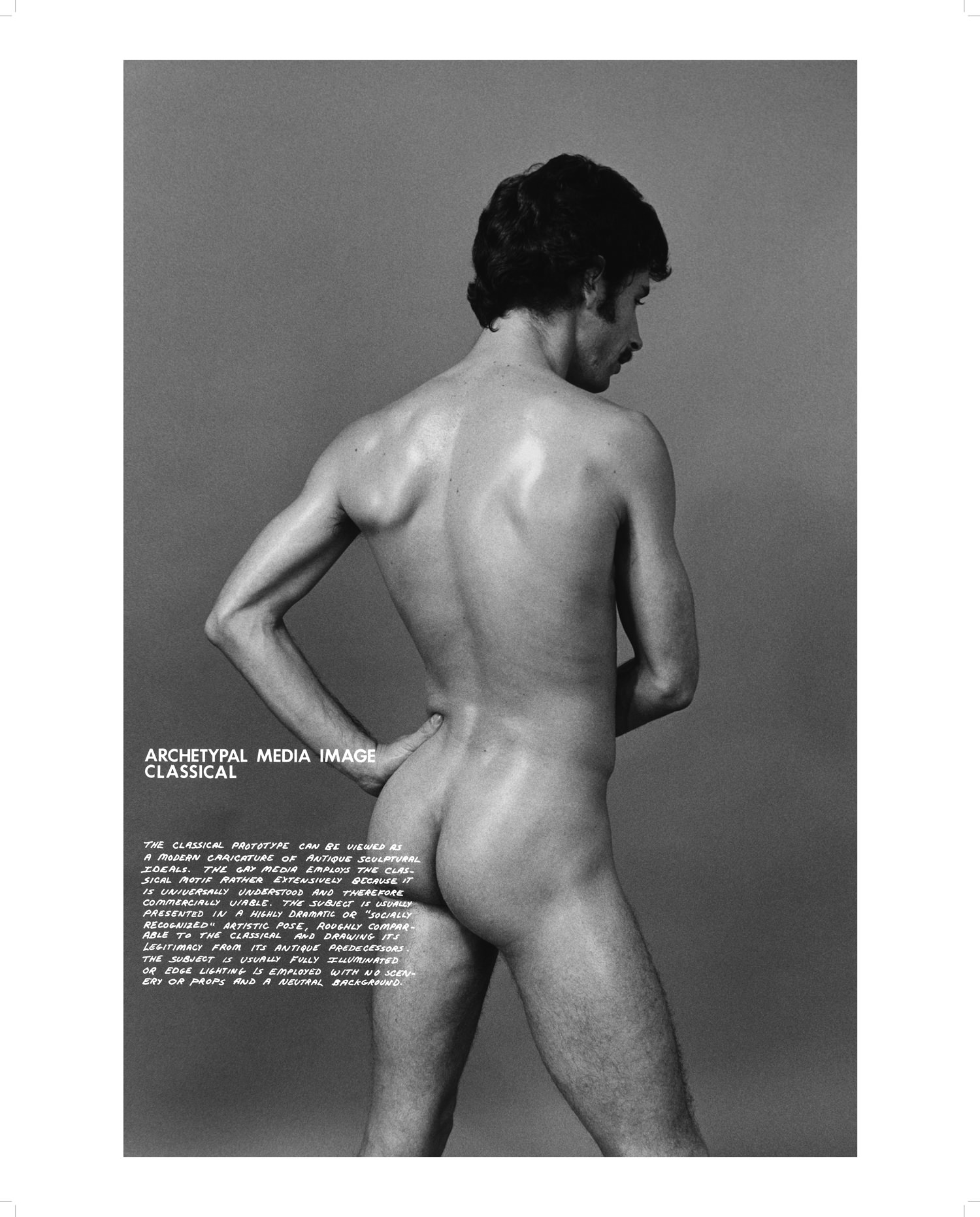

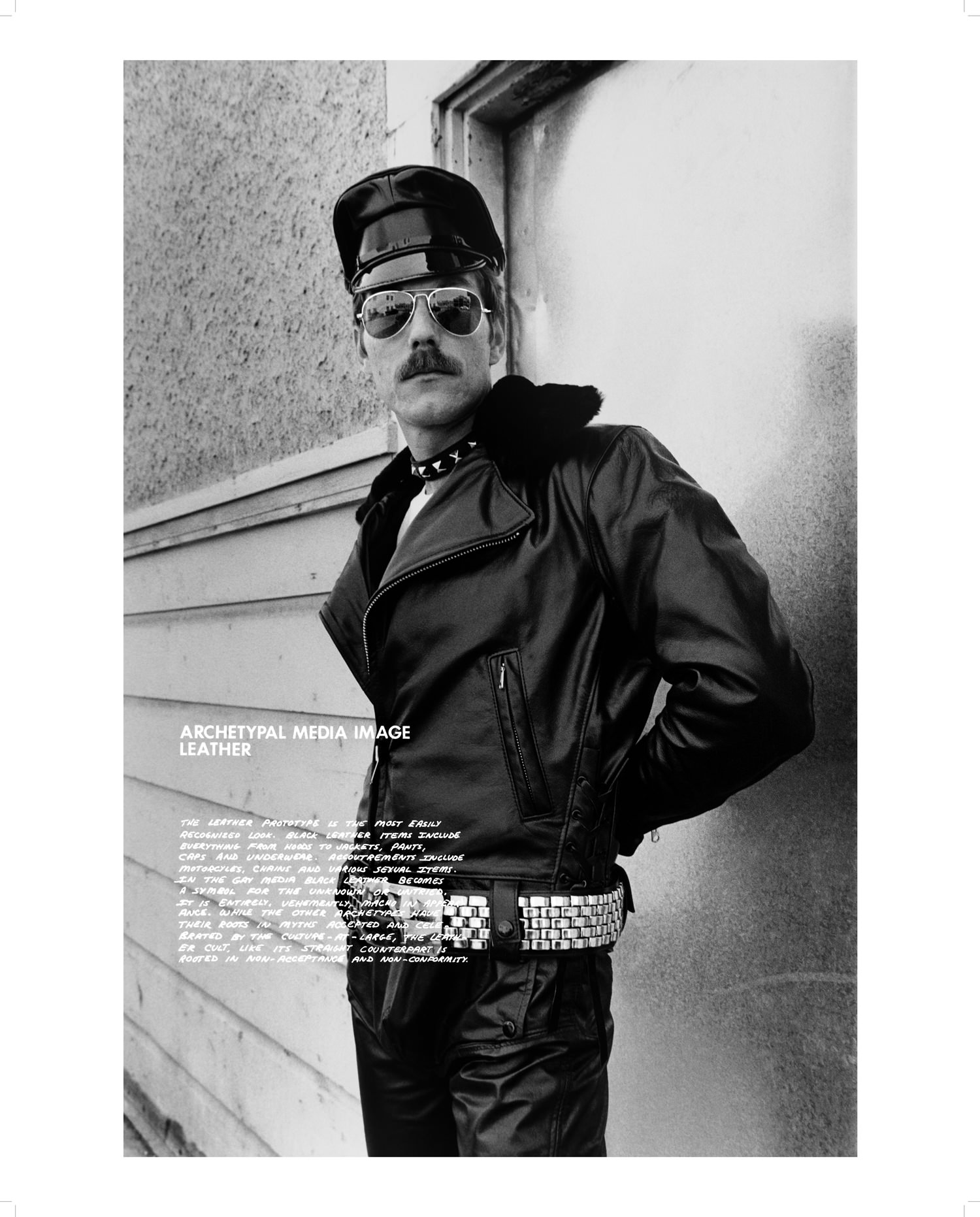

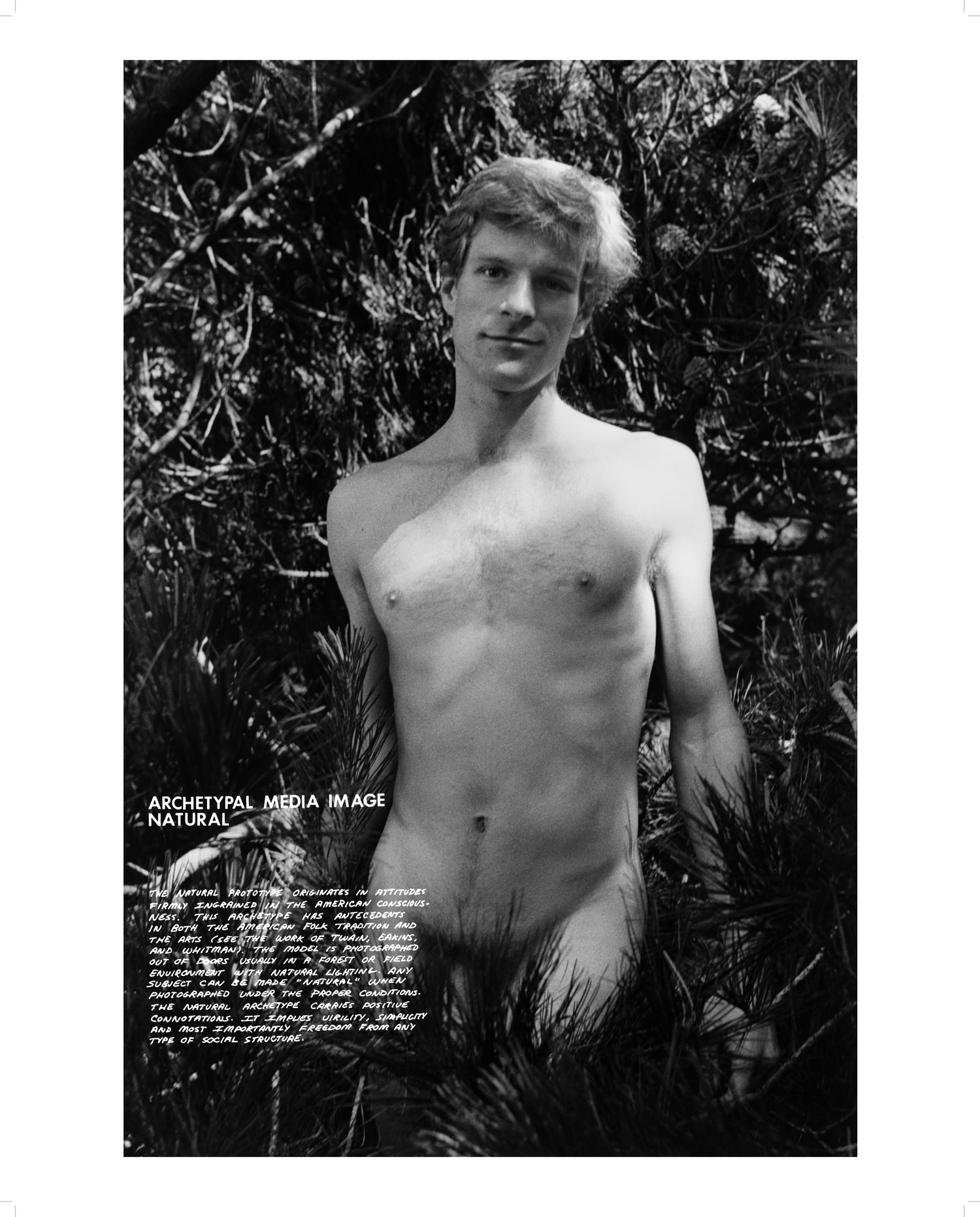

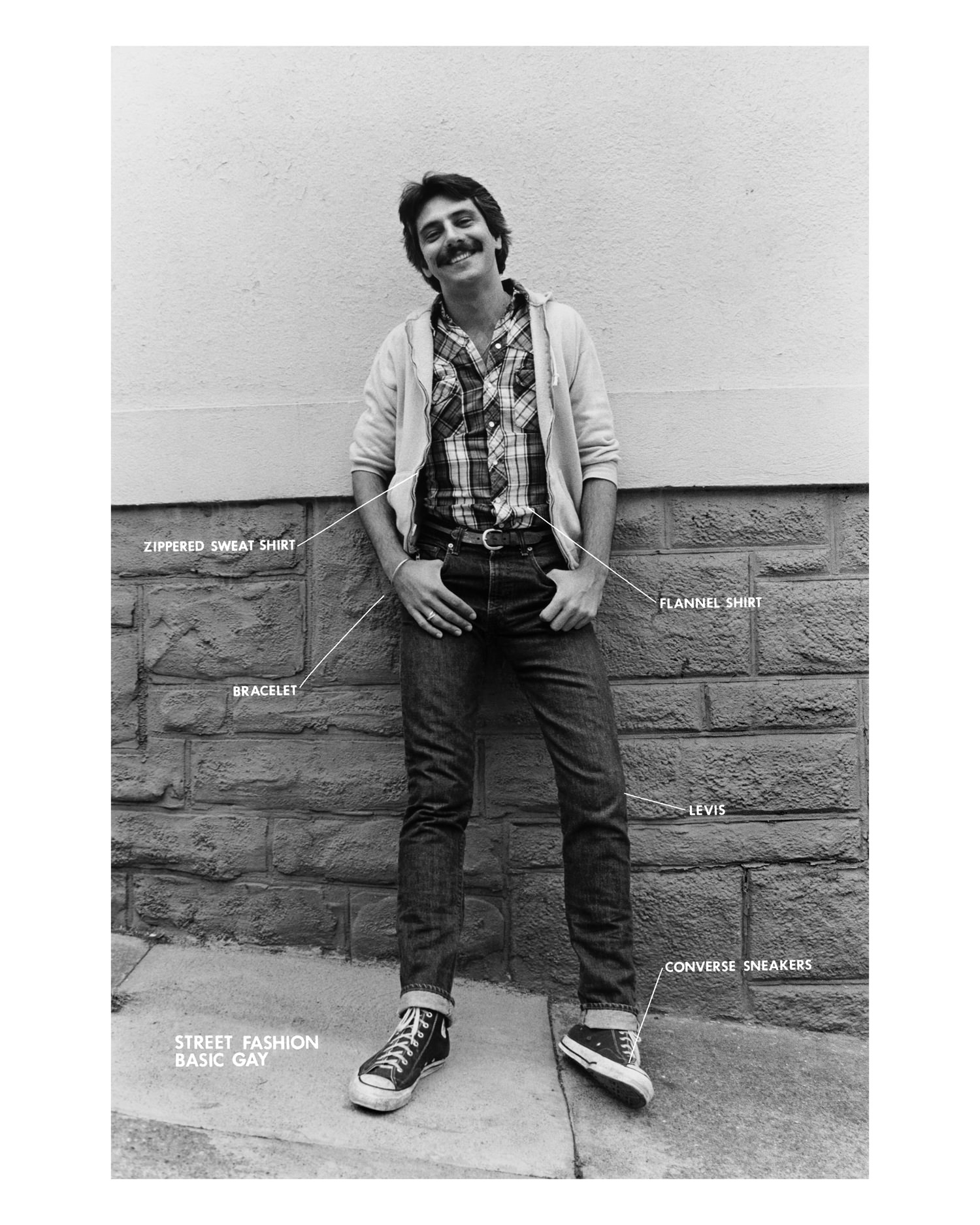

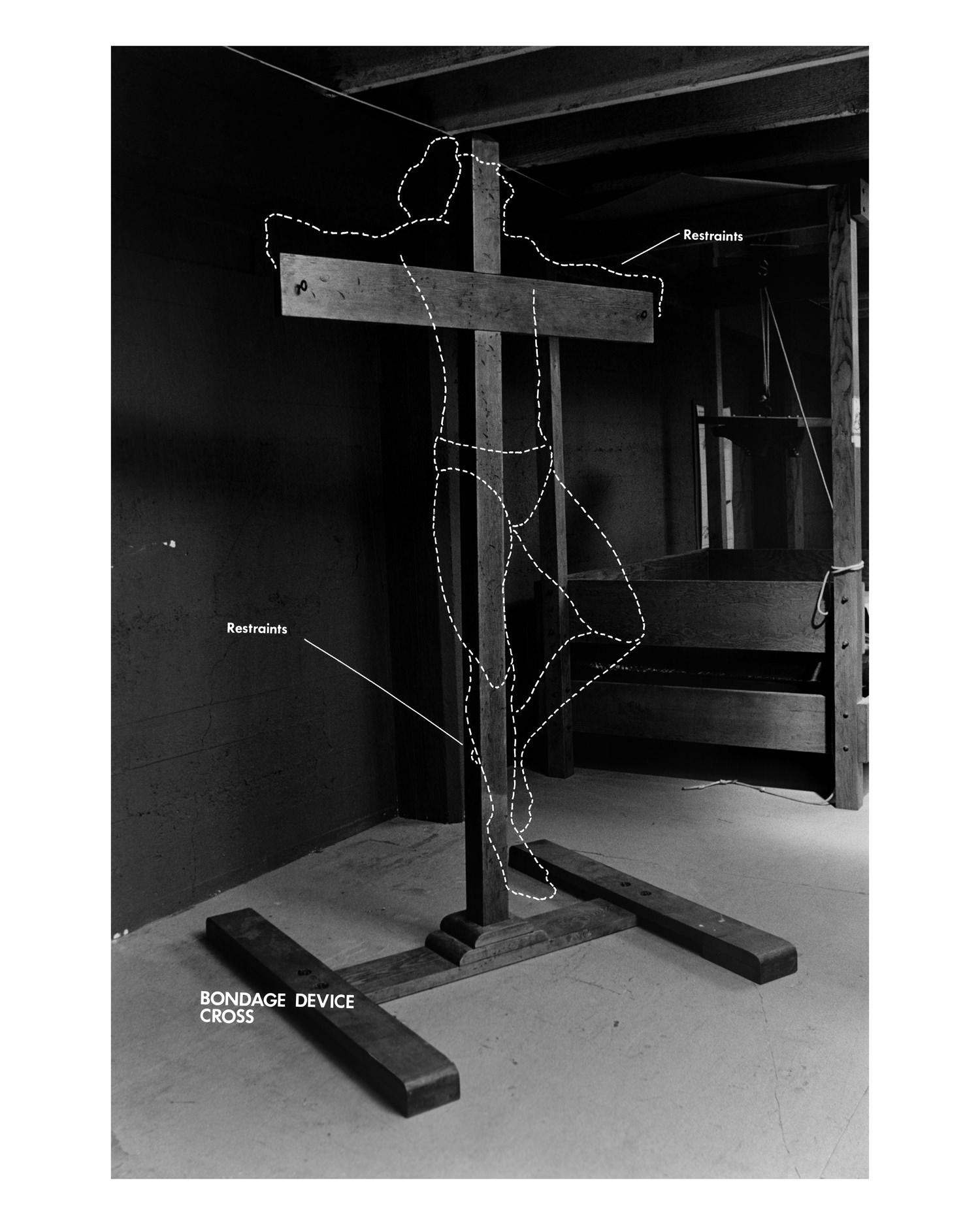

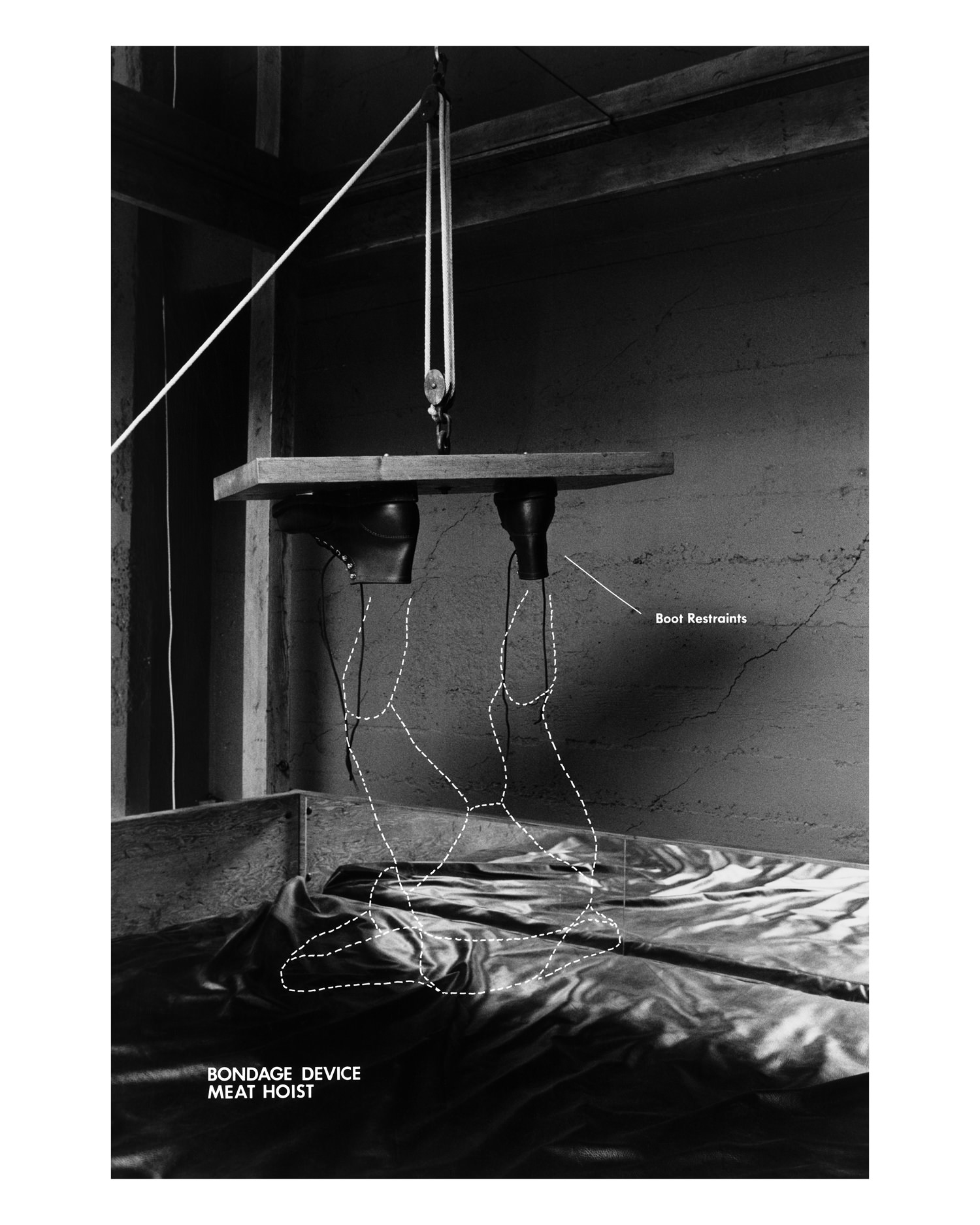

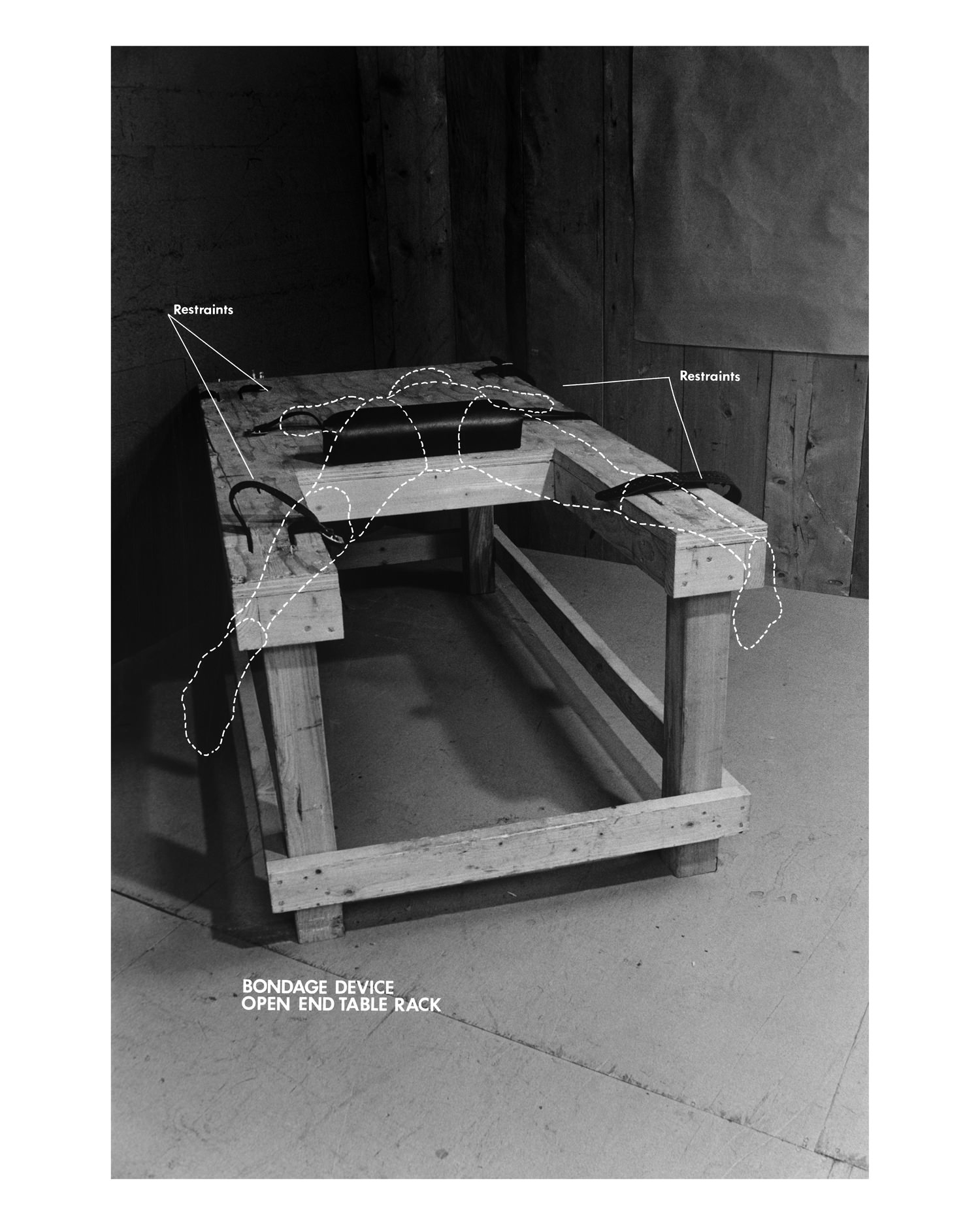

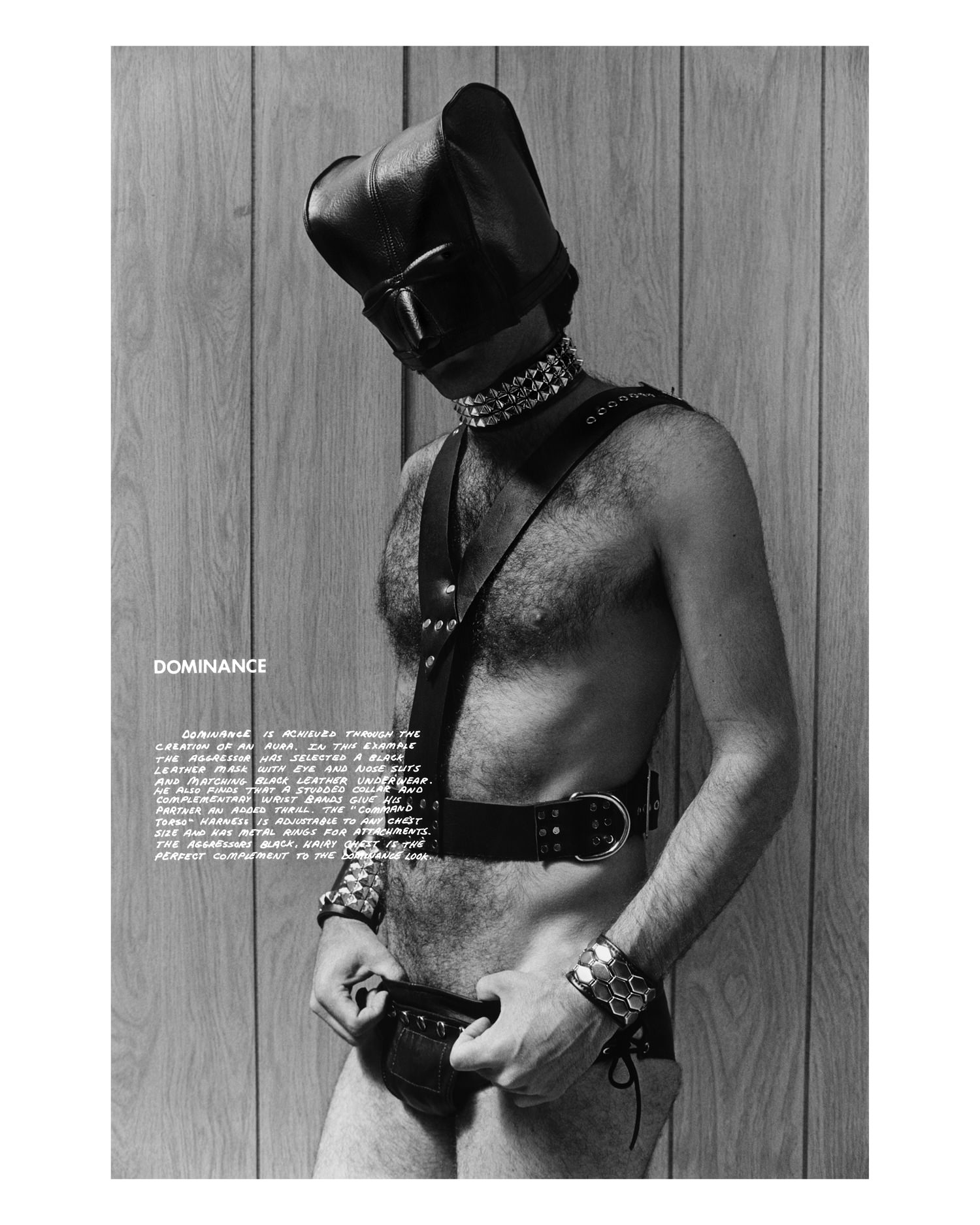

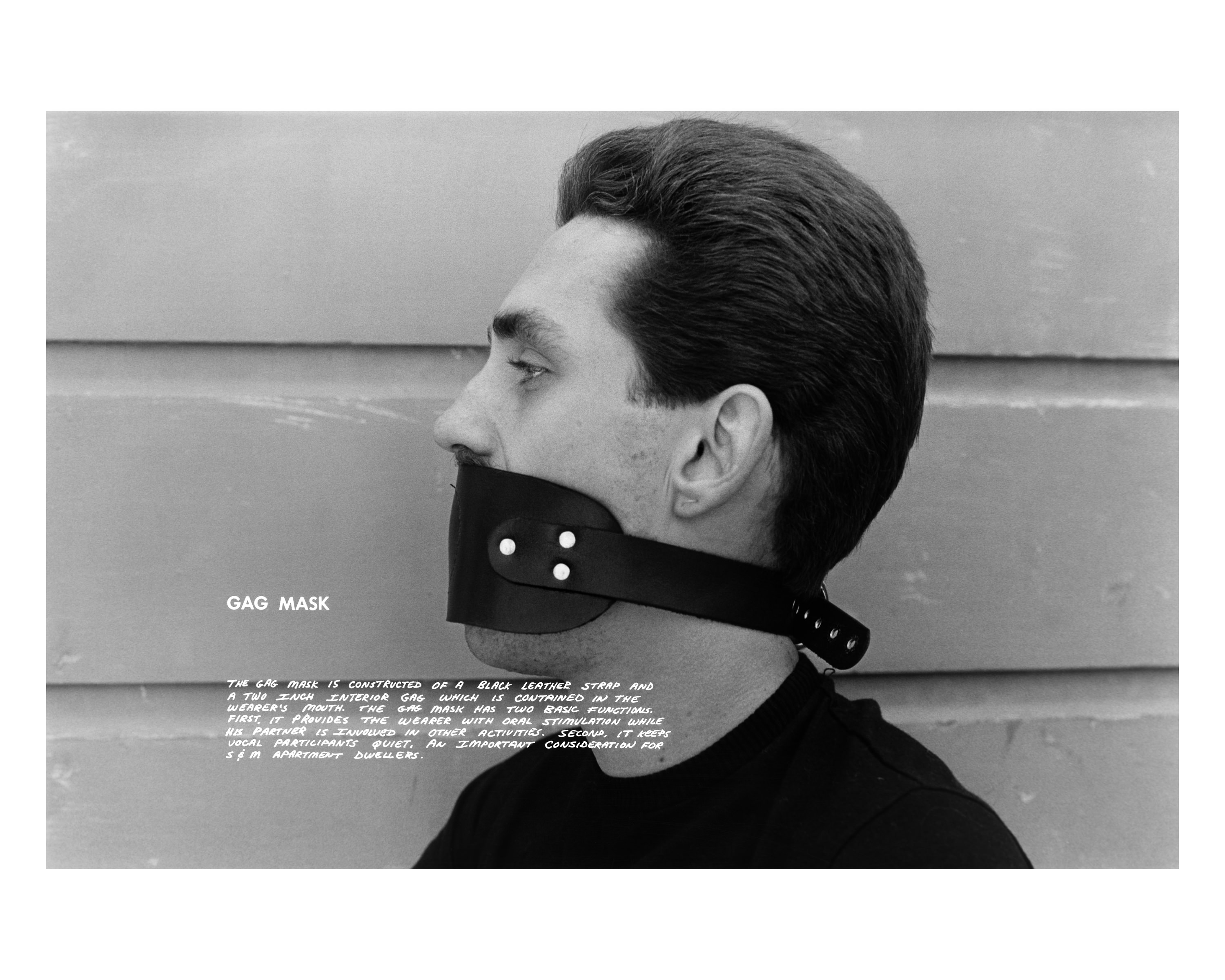

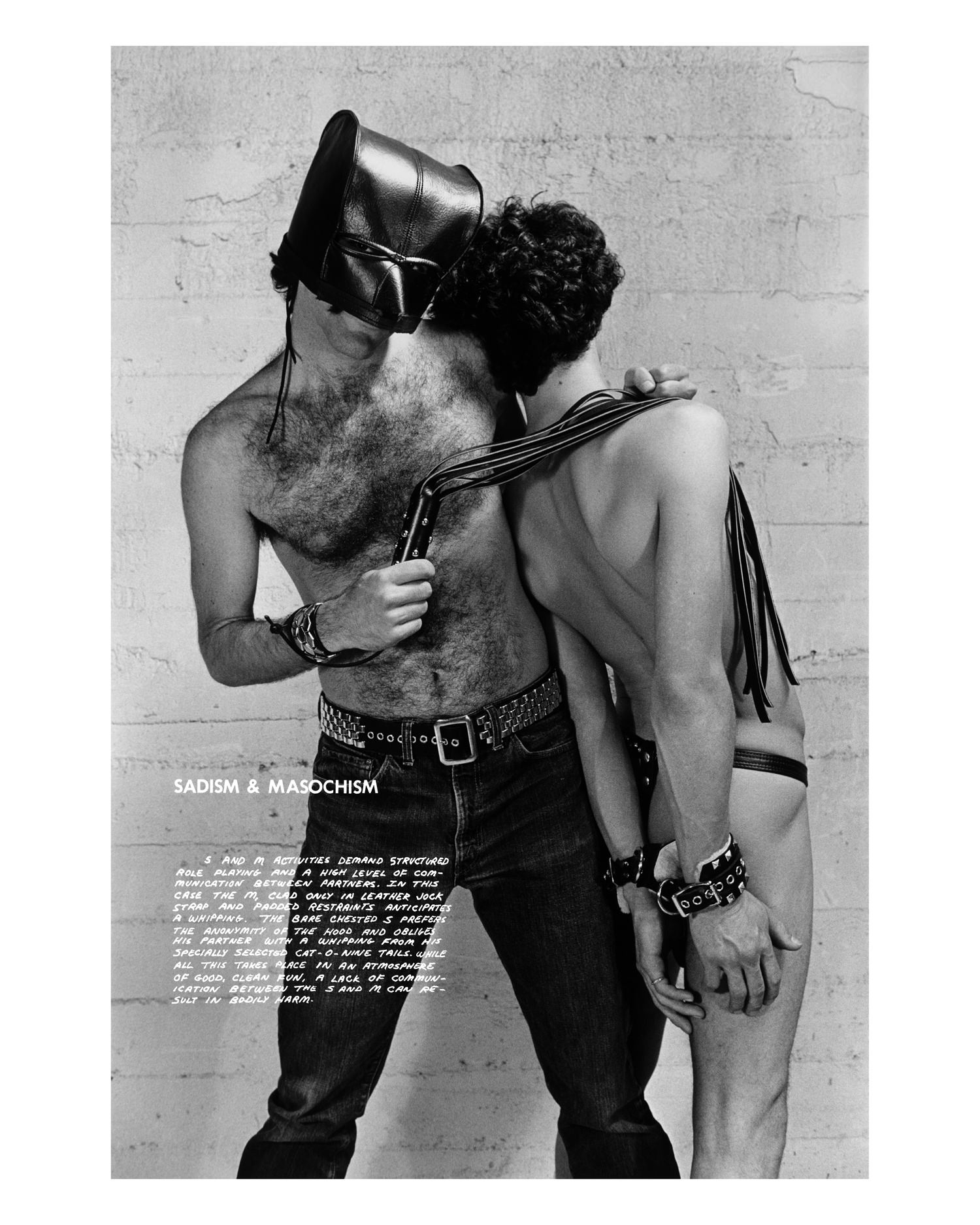

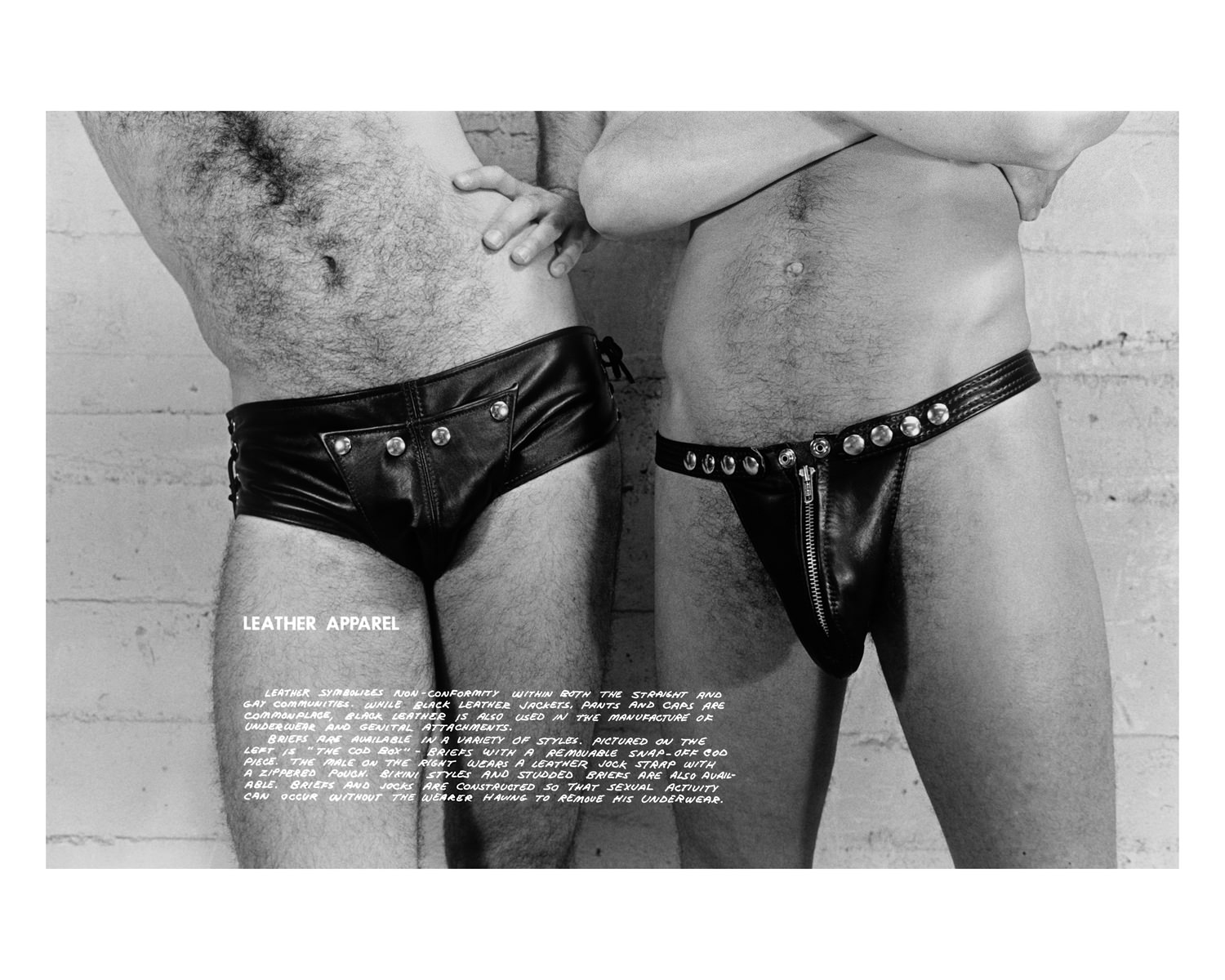

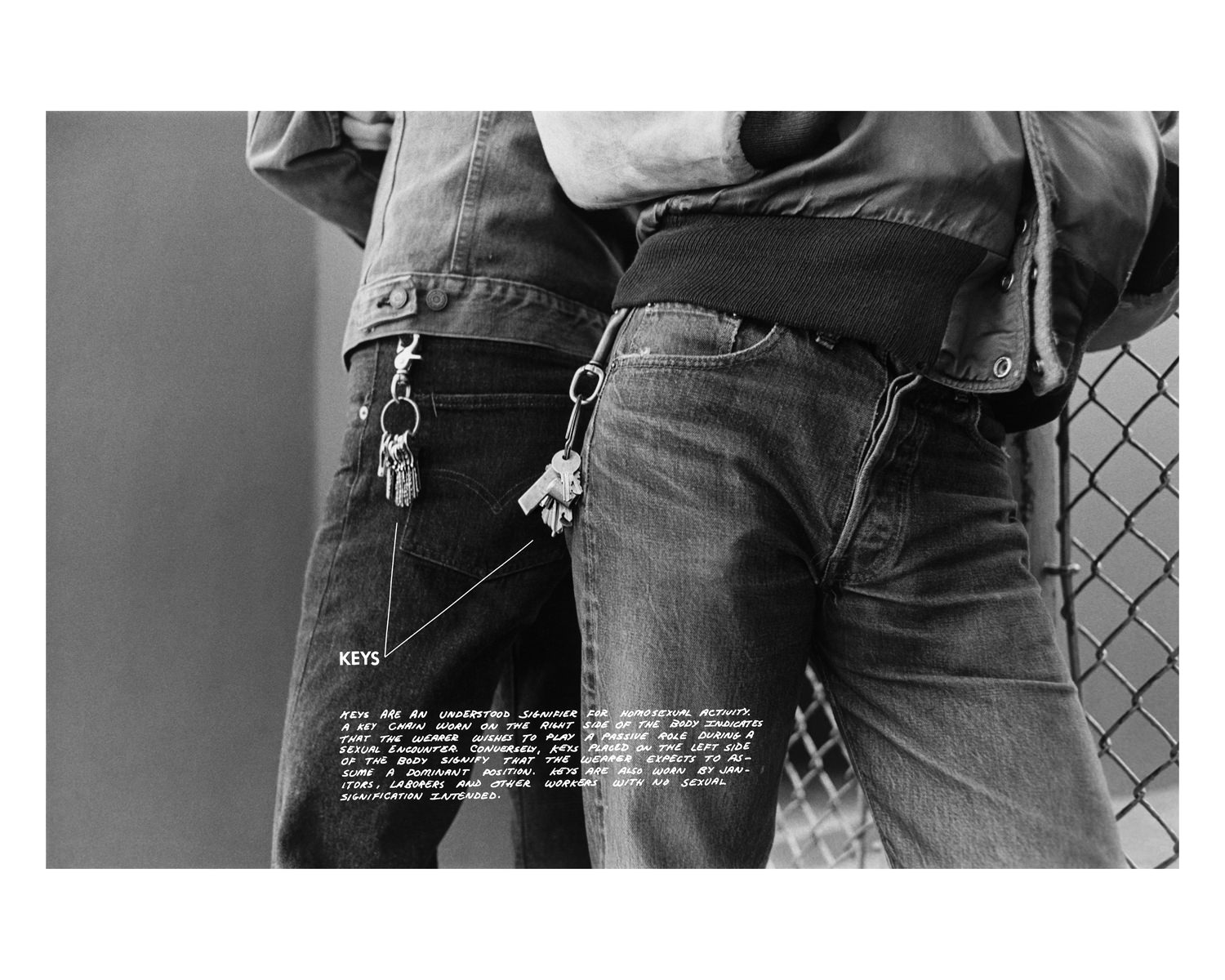

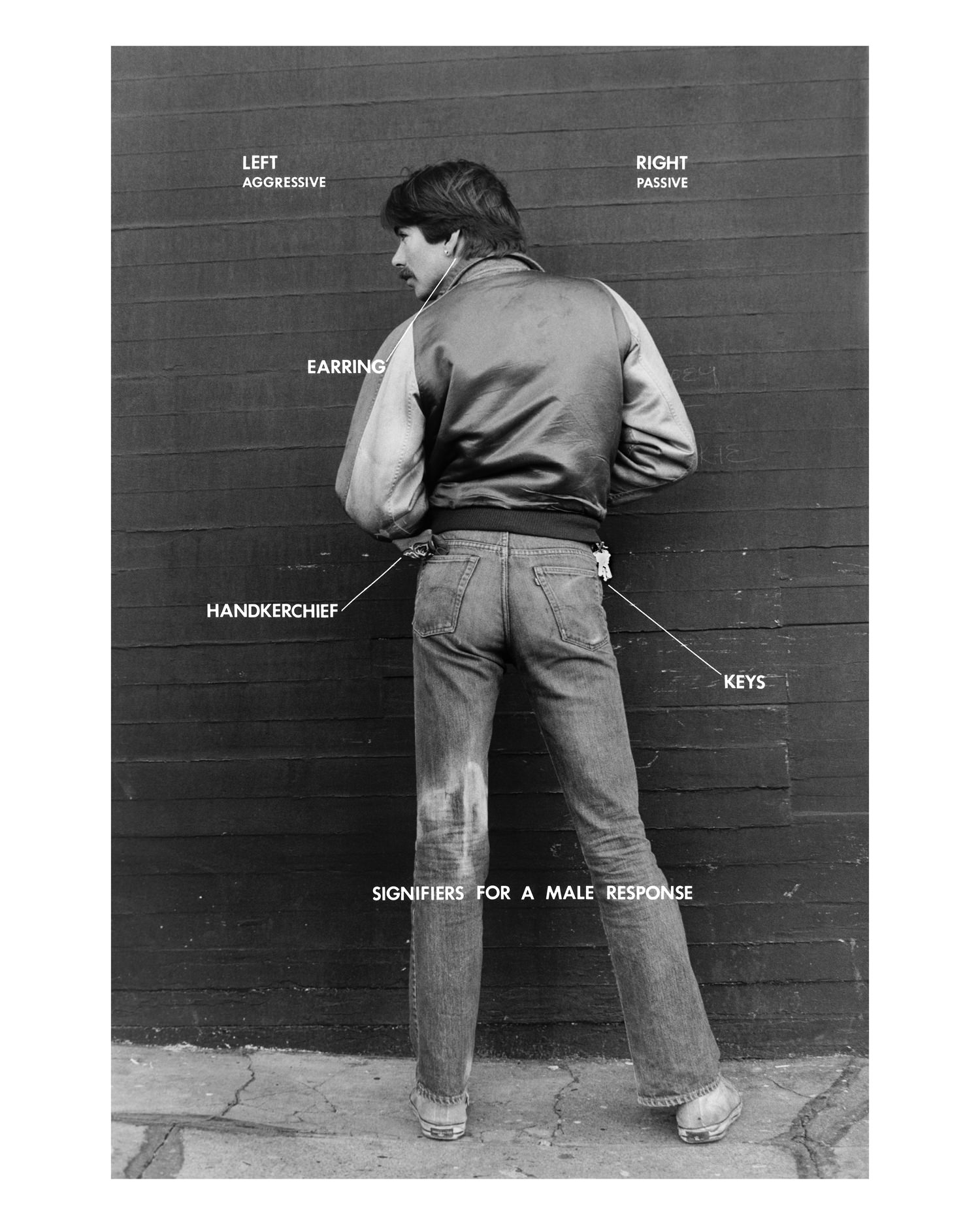

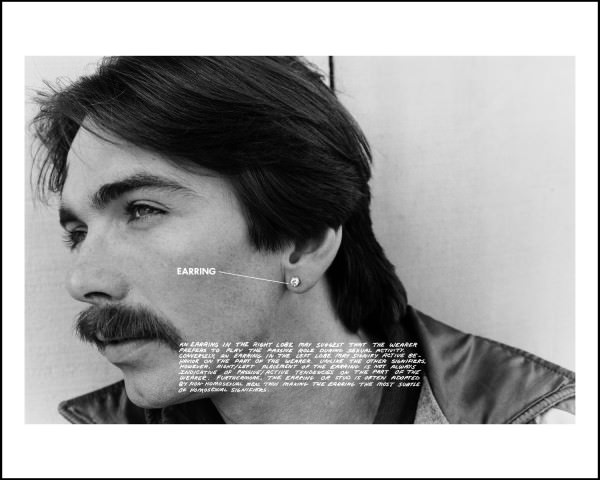

Gay men have a language all of their own. Or so suggests Hal Fischer in his series Gay Semiotics, on view at Cherry & Martin Gallery in Culver City, California until February 21. Fischer photographed men on the prowl in the Castro and Haight Ashbury districts of San Francisco in 1977 as part of a tongue-in-cheek photo essay, labeling the elements of each man’s outfit as part of elaborate cruising codes. The result is a conceptual look at the “gay uniform.” It explains how totally ordinary items in the straight world like handkerchiefs and keychains, when worn in the street by gay men, tell other men about the wearer’s sexual fetishes.

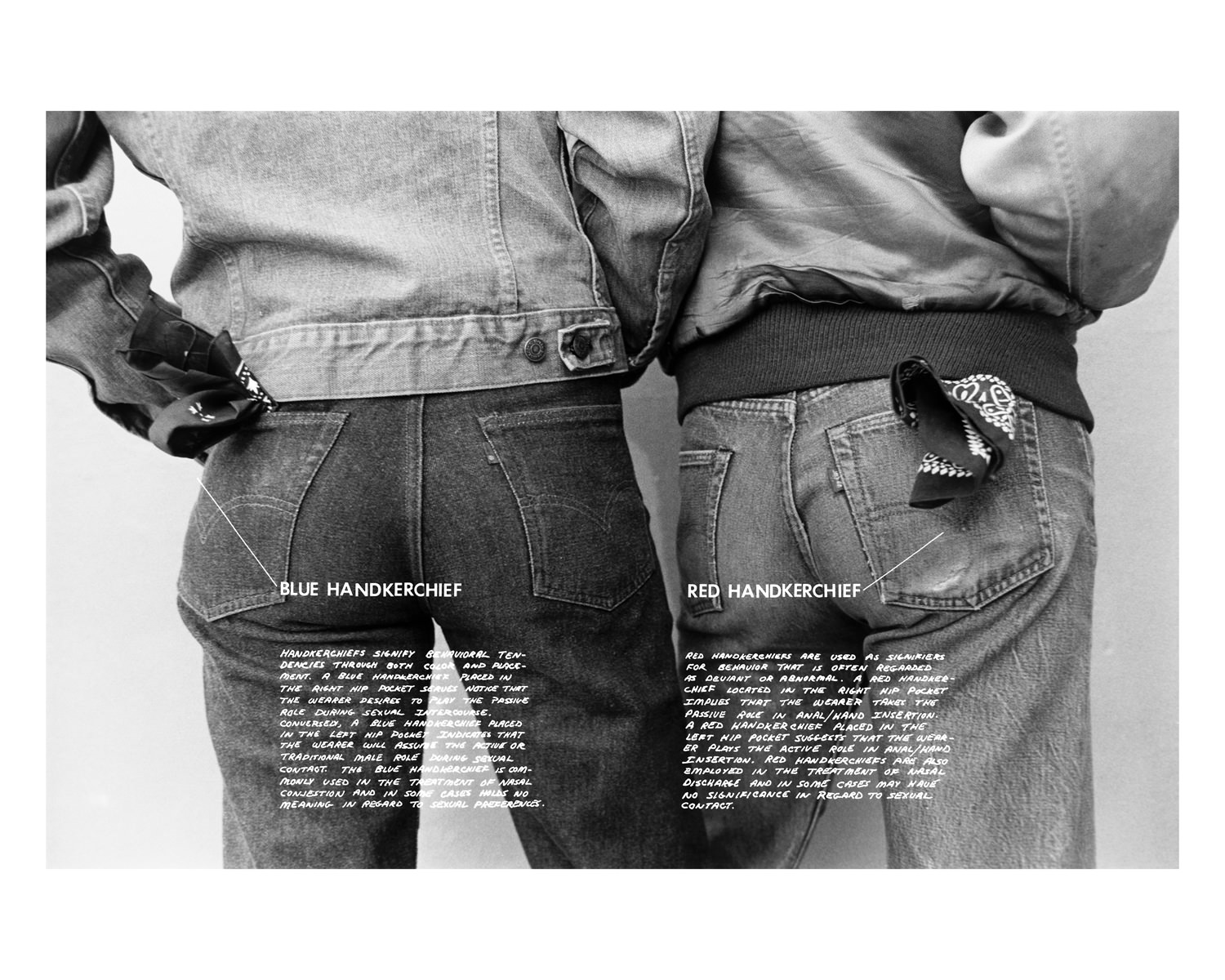

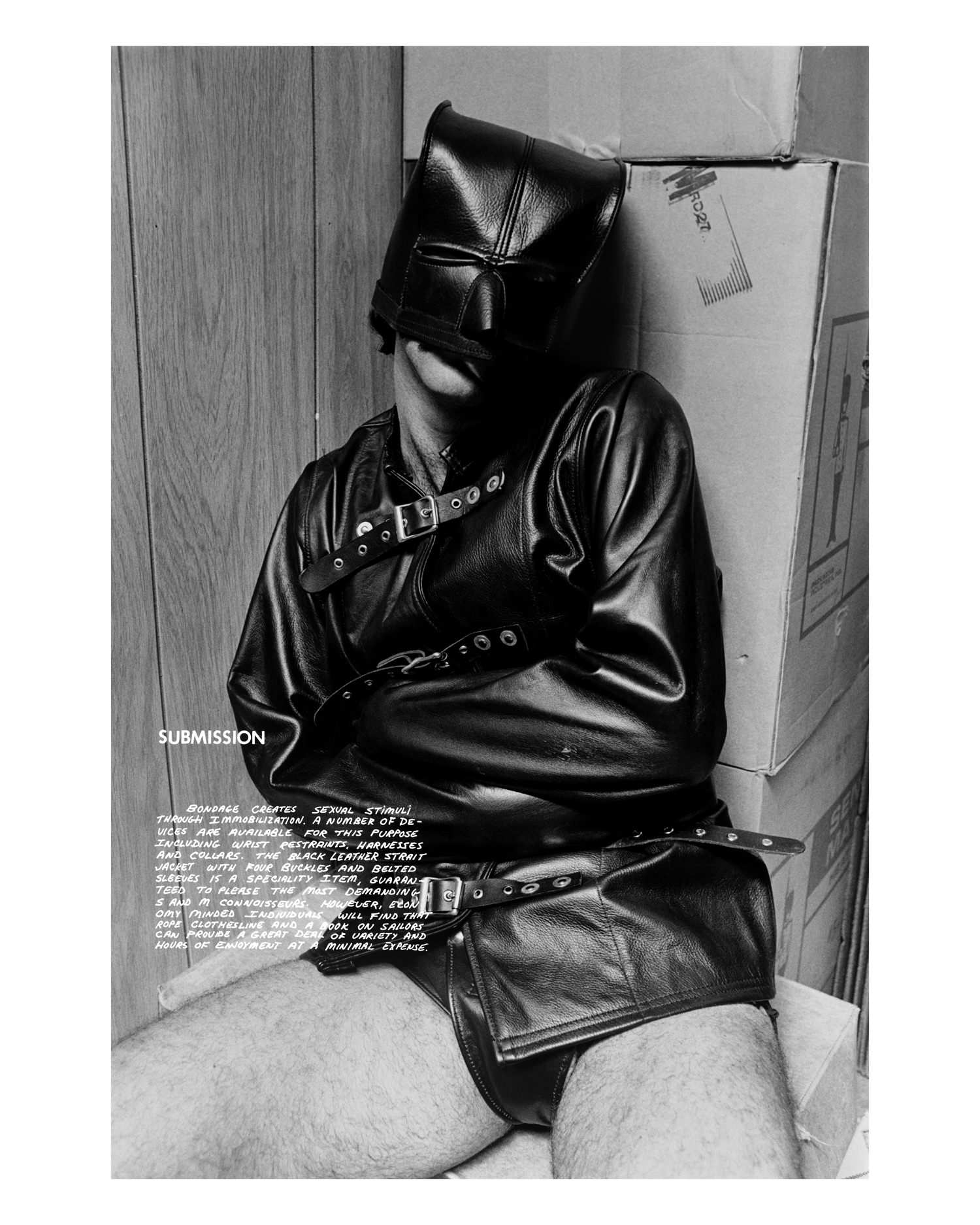

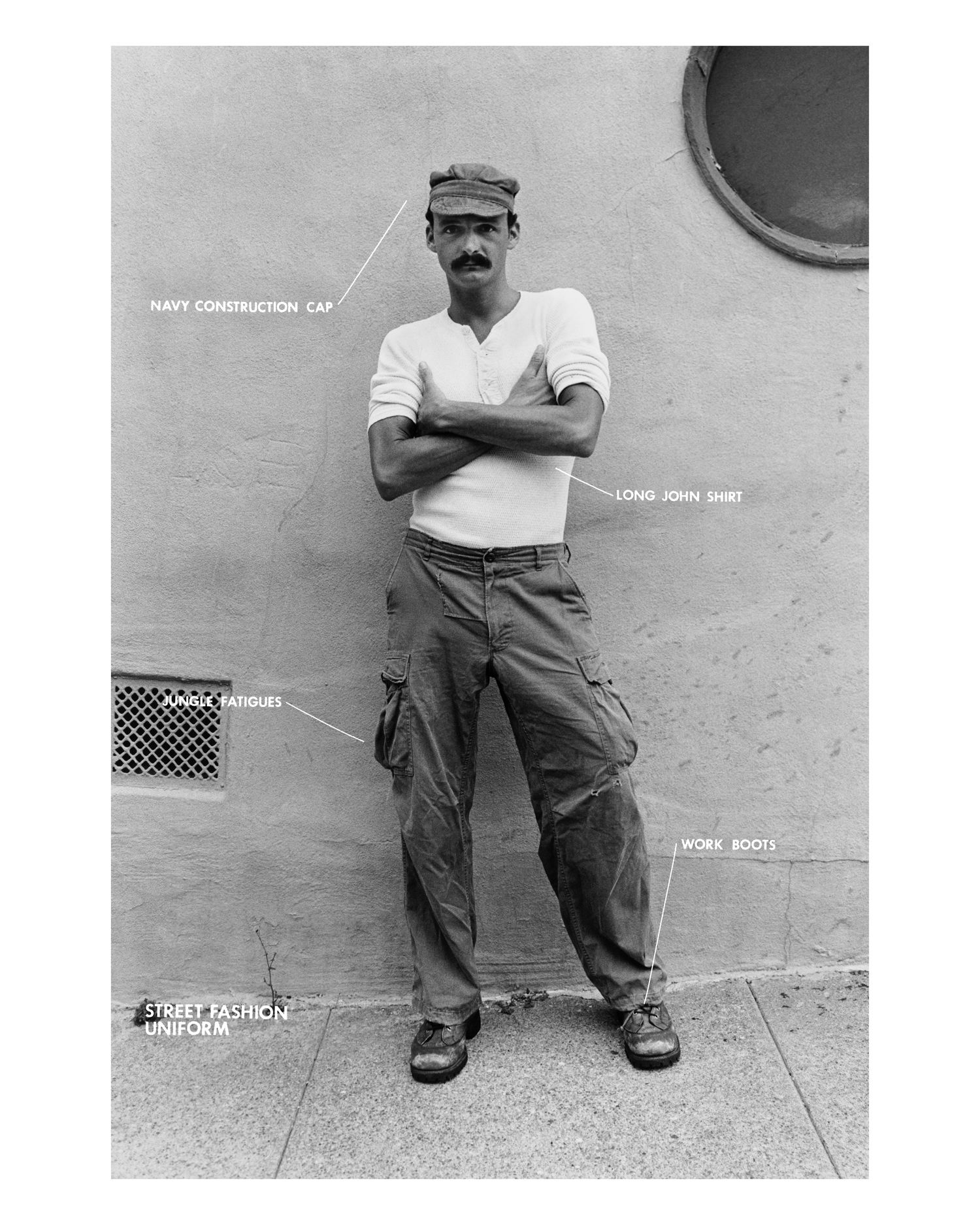

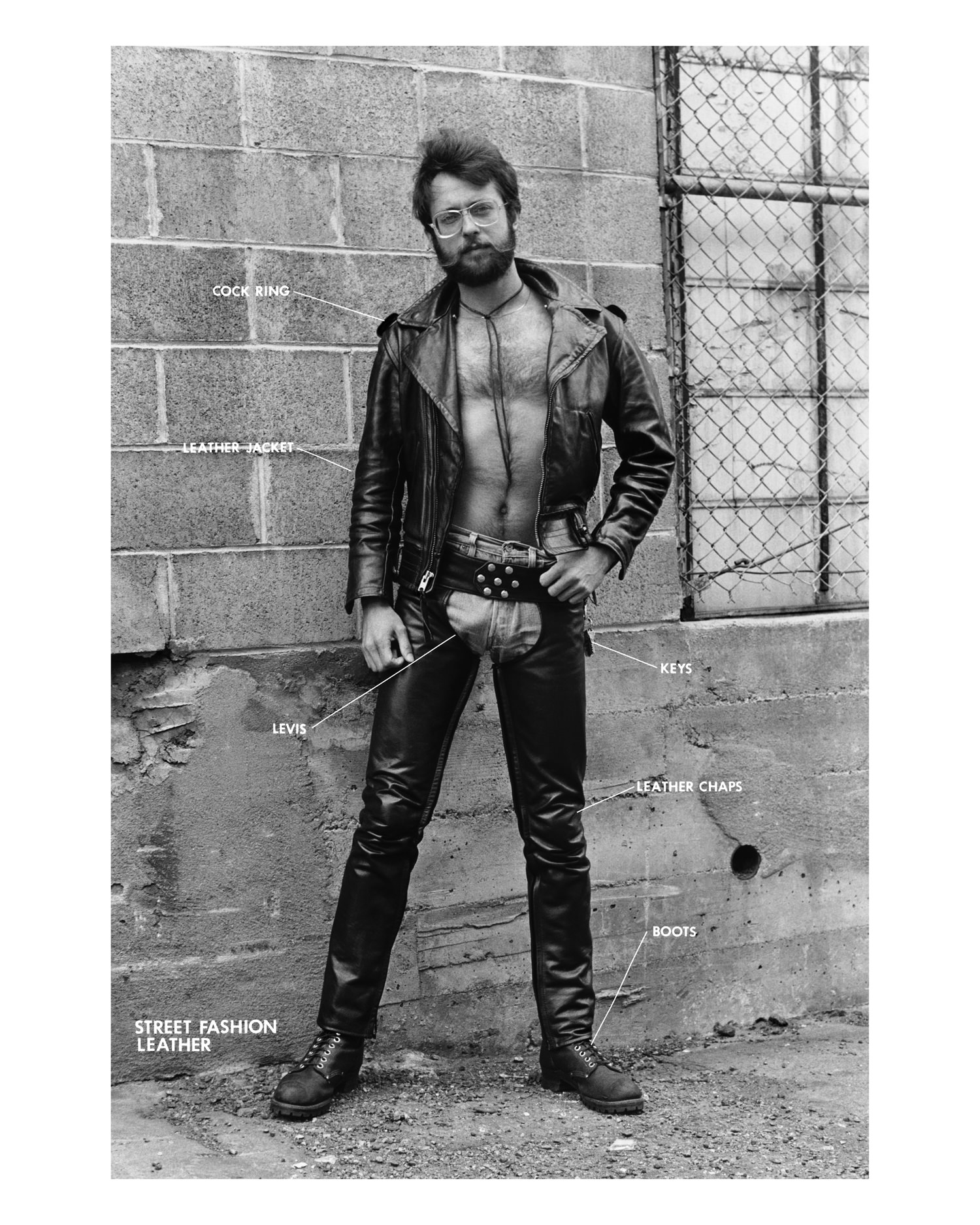

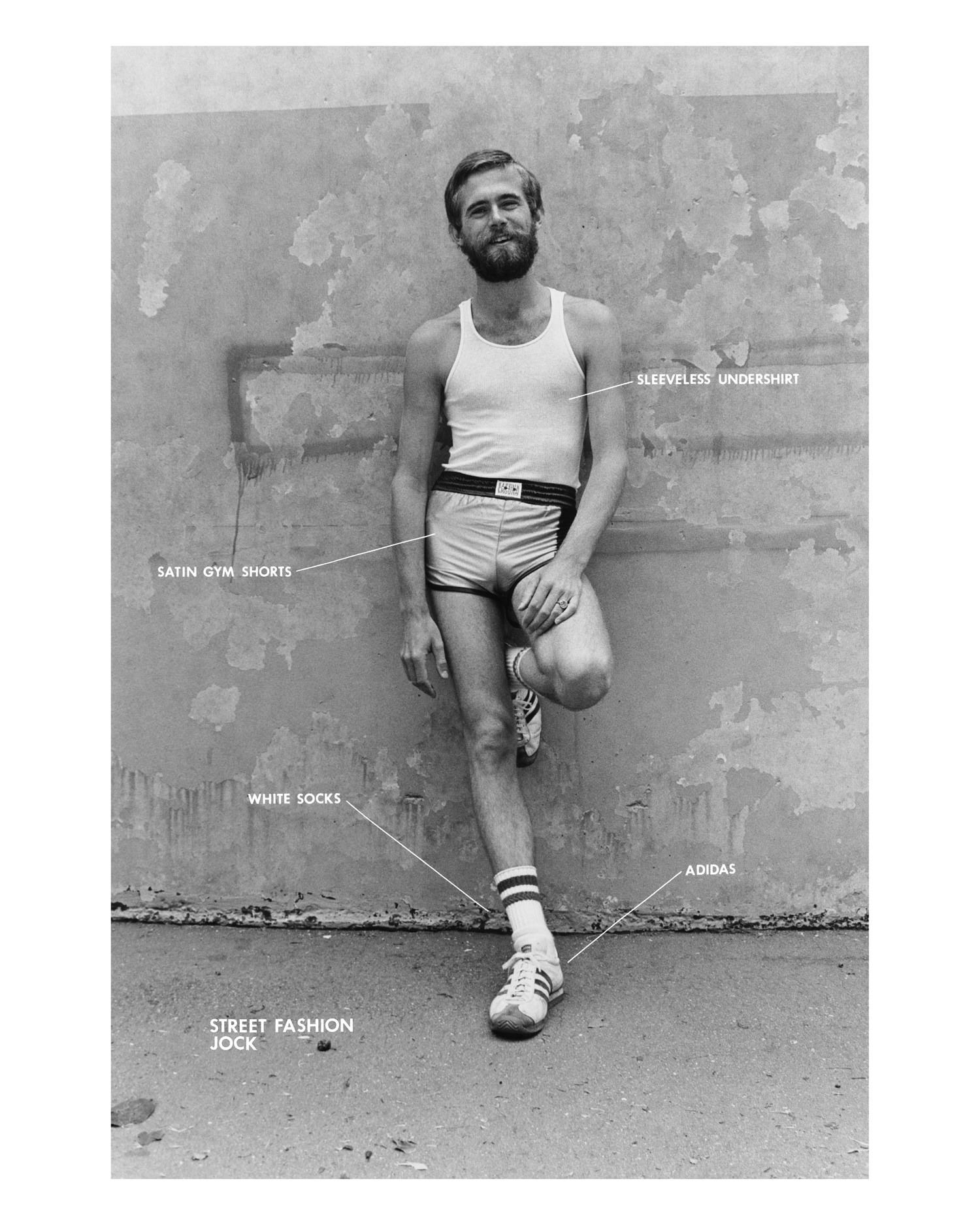

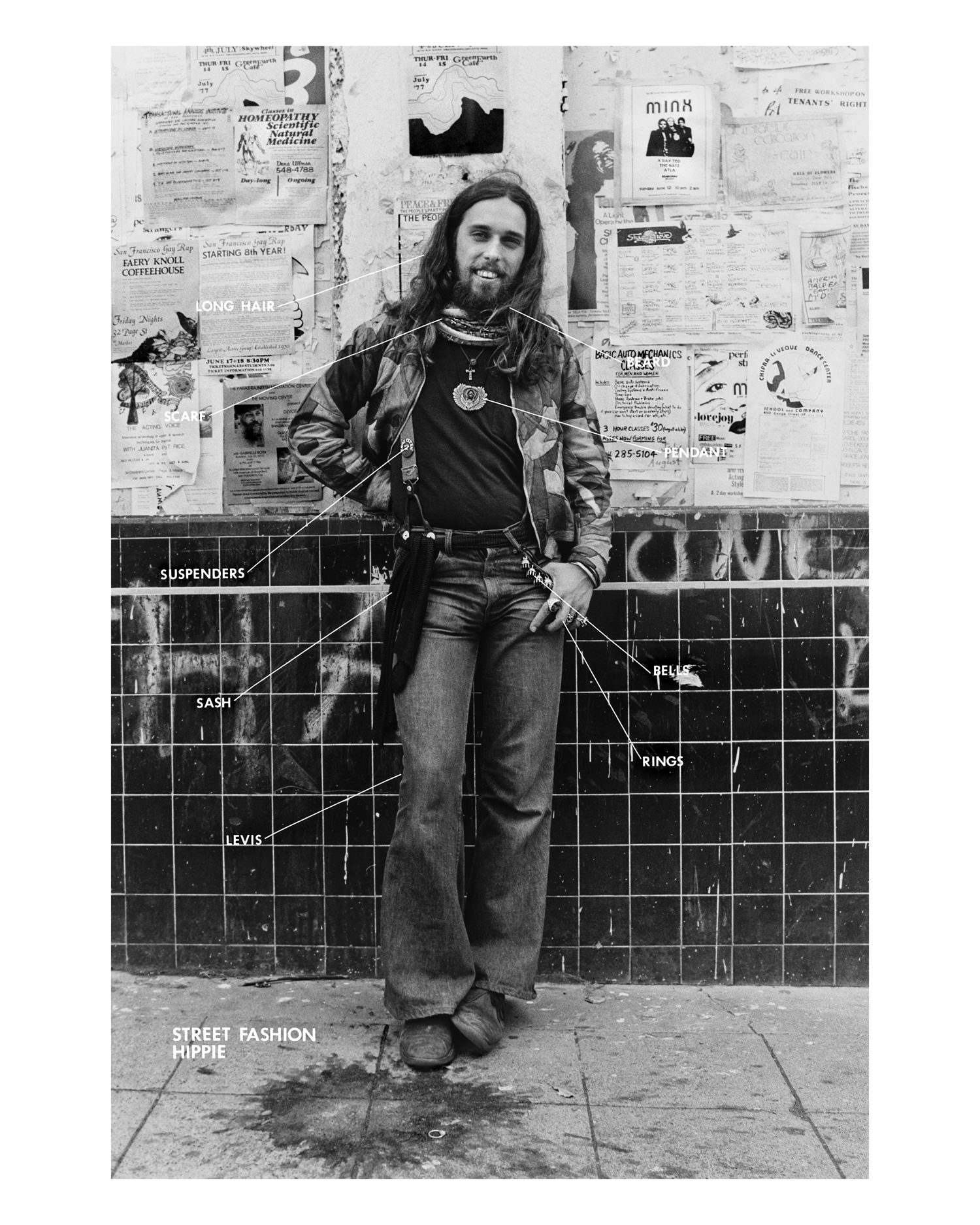

The “semiotics” in the series title refers to semiotic theory, which claims that images and even objects — like words — carry abstract, symbolic meaning. A close-cropped photograph of two asses clad in tight jeans with handkerchiefs in opposite pockets explains the semiotics of “Gay Hanky Code:” “A blue handkerchief placed in the right hip pocket serves notice that the wearer desires to play the passive role during sexual intercourse,” and so on. Other more traditional portraits are broken into types: the Street Fashion Jock in labeled satin gym shorts and Adidas, the Street Fashion Leather in chaps and leather boots, the Street Fashion Basic Gay in flannel shirt and Levis. By merging gay subcultures with art theory, Fischer pulls conceptual photography out of the museum and into the streets (and the back alleys).

The black and white images of mustachioed leathermen in high-wasted flare jeans feel a little dated, maybe because cruising has gone digital. In today’s gayborhoods, though, uniforms have changed but are still in fashion. Fischer’s exhibition is actually timely: it makes us ask how our rapidly evolving hook-up culture has changed the way we communicate and express ourselves in public spaces.