Dietmar Busse, Michael Bilsborough, 2014, Gelatin silver print with ink. Courtesy of the artist.

Interface

Walt Cessna, curator of Interface, sits down with us at the Leslie Lohman Museum to talk art and politics in the 21st century moment.

Walking through the shops and outdoor cafes of SoHo on a spring day can be soul crushing, and overcoming the desire to snuff out your cigarette in that snatched blonde’s $35 plate of truffle fries can take tremendous focus. Surrounded by people whose level of wealth is eclipsed only by their level of Basic, you feel the loss of the vital art that once thrived and then died here, the ghost of which now stares at you blankly from the glittering sockets of a limited edition Damien Hirst skull.

If you’ve ever felt this way, head to the Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art on Wooster Street to see curator Walt Cessna‘s show, “Interface: Queer Artists Forming Communities Through Social Media.” There is still a living heart buried in SoHo, and on a day when the New York Times is announcing Chrystie’s first “Billion Dollar Art Sales Week,” signifying everything that is wrong with the art world, “Interface” at the Leslie Lohman is a sexy and fascinating exploration of what’s right with it.

Photographer/club kid/former fashion terrorist Cessna has gathered a truly heterogenous group of “mostly New York-based artists with active studio practices” who all “have (or have had) active relationships with social media” in an effort “to understand how this truly 21st century confection could create community and bring success to these artists.” What emerges is a titillating and uplifting picture of the 21st century working artist: entrepreneurs who can tap into the queer potential of a democratized online world to display their work, interact with fans and markets, and connect to each other outside the tyranny of galleries who must cater to the über rich.

“The show is a bit of a hodgepodge,” Cessna says, “painting, photography, illustration, video, installation, performance, sculpture, embroidery and needlepoint, everything but the proverbial kitchen sink.” Furthermore, there seems to be no prevailing similitude between how the artists in the show use social media; their various relationships to it are as different from each other as their work is. This broad spectrum of relationality underscores how the social media experience has changed the art-making, not just the art-promoting, game: while most of the artists have utilized various online platforms to build their brands, show their work, and find markets that say “yes” in a world of galleries saying “no,” some of them have gone so far as to incorporate a consciousness of social media into their actual creative process. Take Ben Copperwheat, whose “Divas” series featuring depictions of Madonna, Diana Ross, Joan Rivers, and BritCunt Margaret Thatcher is on display in the show, and who embraces the use of Instagram so thoroughly that “the nature of the square format has led me to create my compositions to work within the space to maximum effect.”

The means of distribution is shaping the work at the site of its production. In reading the artists’ statements it’s clear that Cessna has gathered creators whose relationships to social media aren’t all peaches and glitter; plenty of the artists speak of it with annoyance, or ambivalence, or an admission that the relationship has changed over time. Artist Chick Byrne captures a kind of generational ennui, remarking that “social media had its birth for me around the time I turned 12. AIM and chat rooms were it, and everybody was typing…. Now that I have spent more than half my life on social media, the appeal has mostly faded. My online presence is minimal and my eagerness to use it just as low.”

With a mix of swooning nostalgia and electrified conviction, Walt harkened back to the days of the Early 1980s East Village art scene, stitching that moment to the present with common threads of a “do-it-yourself aesthetic and punk ethos,” as well as a seismic shift in the economic and practical aspects of how and where art gets consumed. Today it’s tumblr feeds and Facebook walls, in 1982 it was subway cars and bathroom stalls. It was a time when the prevailing gallery system was being challenged by radical means of dissemination, as well as artists who were determined to subvert the calcification of the “proper” art world. Many of these artists were queer, and their ability to think outside the box was a result of lives that had been lived in society’s margins. Walt looks for this unabashed ferocity in queer artists today, dismissing those who put “less of their penis online and more of their commerce,” — those who might sublimate authentic queer radicalism for the kind of bourgeois self-consciousness that can sometimes emerge in the wake of increasing online success. Cessna has no patience for artists who “look correct but have no politics,” especially in an age when the problematic side of social media can mean that “hitting the like button excuses you from having to think about it at all.”

With its focus on queer methods of resistance and conscious art-making for a new age, “Interface” could not have a more appropriate home than the Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art. Founded like a giant “fuck you” to death during the darkest days of AIDS, a time when gay businesses and galleries faced extinction as gay corpses mounted with no end in sight, Leslie Lohman has been serving queer resistance since day one. They own their space (as well as the 7,000 sf of space next to them which they’re about to take over), and in 2011 they made the critical jump from a gallery to a fully accredited museum — the strategic importance of which should not be missed: as a museum with an endowment, rather than a gallery dependent on sales (which must always be sky-high to satisfy the vice grip of ever-rising SoHo rents), the Leslie Lohman can perform a critical function in our community, allowing their rotating guest curators to build shows that don’t need blue-chip sales, shows that can focus instead on queer artists who deserve to be seen but haven’t yet received the powerful benevolence of exposure in prestigious galleries. Thus, Walt Cessna can fill his show with the artists who he knows to have politics as rigorous as their aesthetics, without giving a shit as to whether or not they can command million dollar price tags.

Walt talked passionately about how the Leslie Lohman is not known enough by the young and the hip of the NYC queer art world, and his hopes that this show can help enlighten that particular crowd to the vital role the museum can play in furthering the kinds of democratization and destratification that social media platforms have already begun for queer artists. The museum can promote those who might be stuck in what Walt called “a kind of online purgatory, where they’re known as an Internet celebrity, but they’re not in the galleries yet. Here, the fans get the chance to physically view the artists’ work, and something happens in that space between the viewer and the work that can’t happen online.”

Below is a preview of what you’ll see at the show:

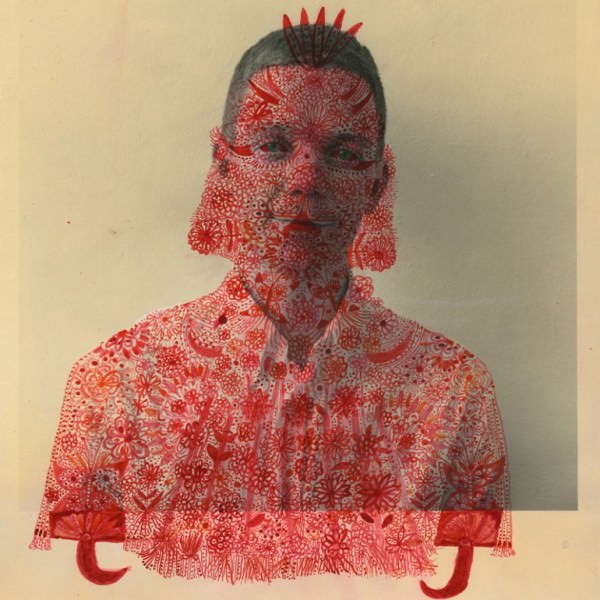

Bubi Canal, Untitled, 2015. Courtesy of the artist in Munch Gallery, NY.

Bubi Canal, Untitled, 2015. Courtesy of the artist in Munch Gallery, NY.

Derek Dewitt, Stella Rose Saint Clair, 2013, Courtesy of the artist.

Derek Dewitt, Stella Rose Saint Clair, 2013, Courtesy of the artist.

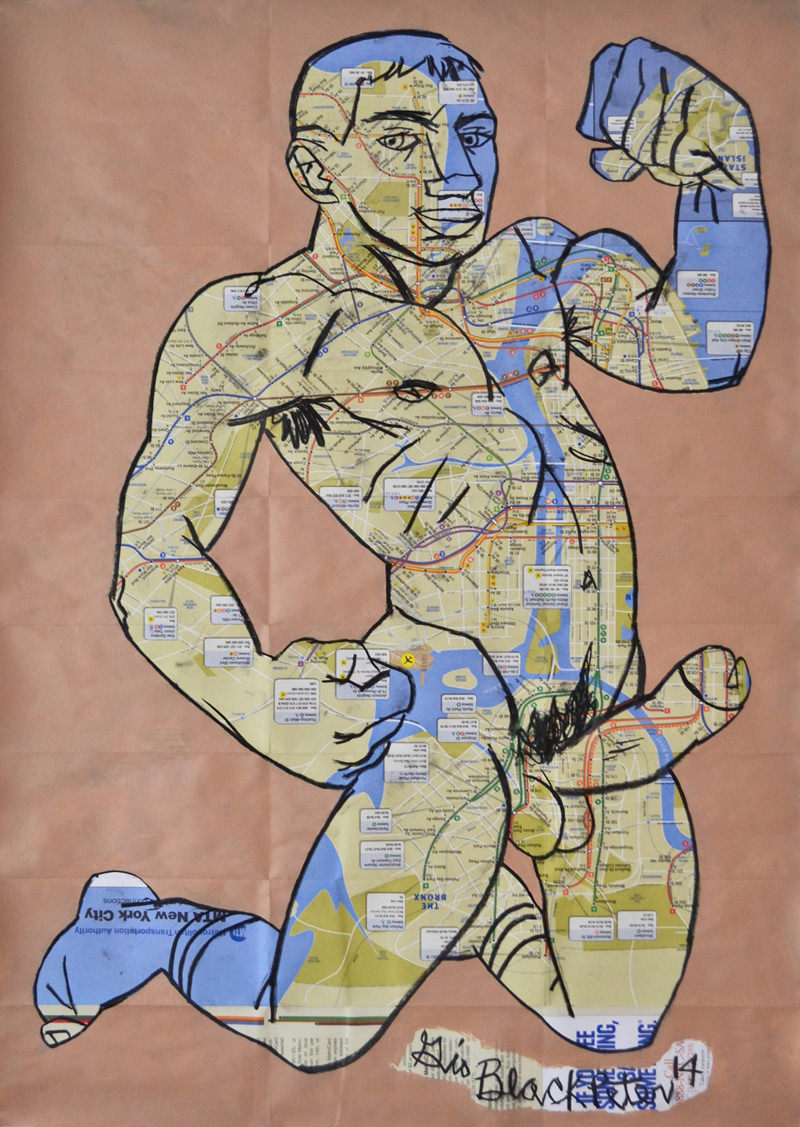

Gio Black Peter, Big Dreams, 2014, Acrylic and oil pastel on NYC Subway map. Courtesy of the artist.

Gio Black Peter, Big Dreams, 2014, Acrylic and oil pastel on NYC Subway map. Courtesy of the artist.

Brian Kenny, Eye Get It, 2015, Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

Brian Kenny, Eye Get It, 2015, Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

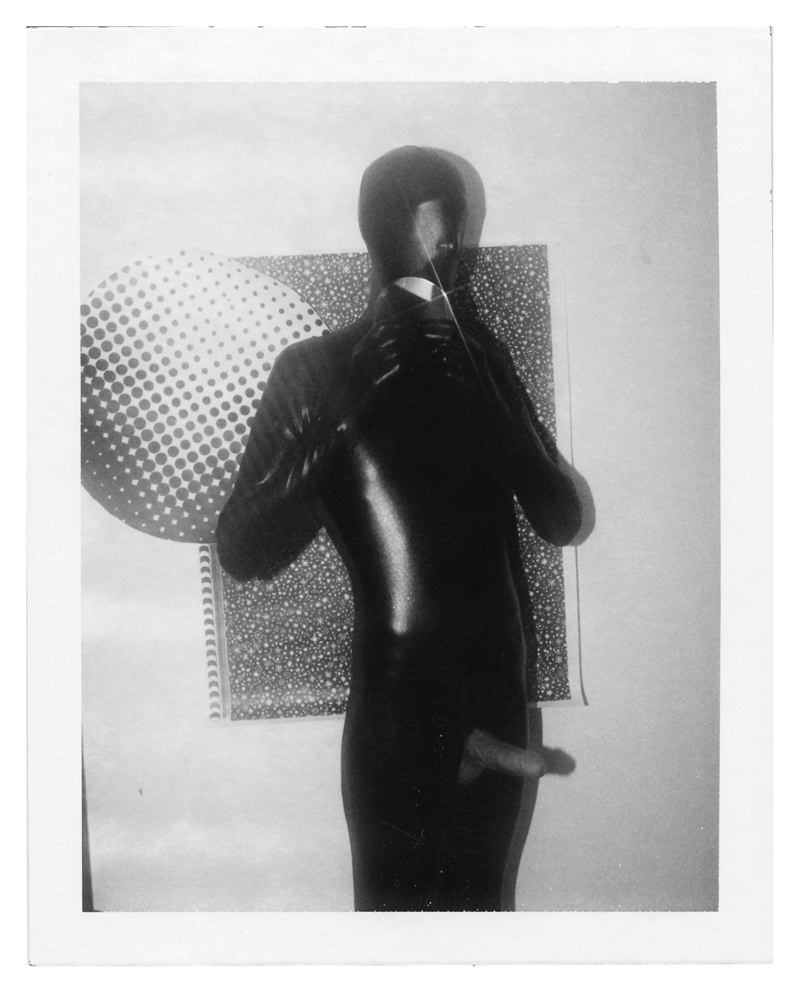

Benjamin Fredrickson, Anonymous (Spandex), 2007, Polaroid. Courtesy of the artist and Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York.

Benjamin Fredrickson, Anonymous (Spandex), 2007, Polaroid. Courtesy of the artist and Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York.

‘Interface: Queer artists forming communities through social media’ is on view from May 15-Aug 2, 2015 at Leslie-Lohman Museum, 26 Wooster St. NY, NY.