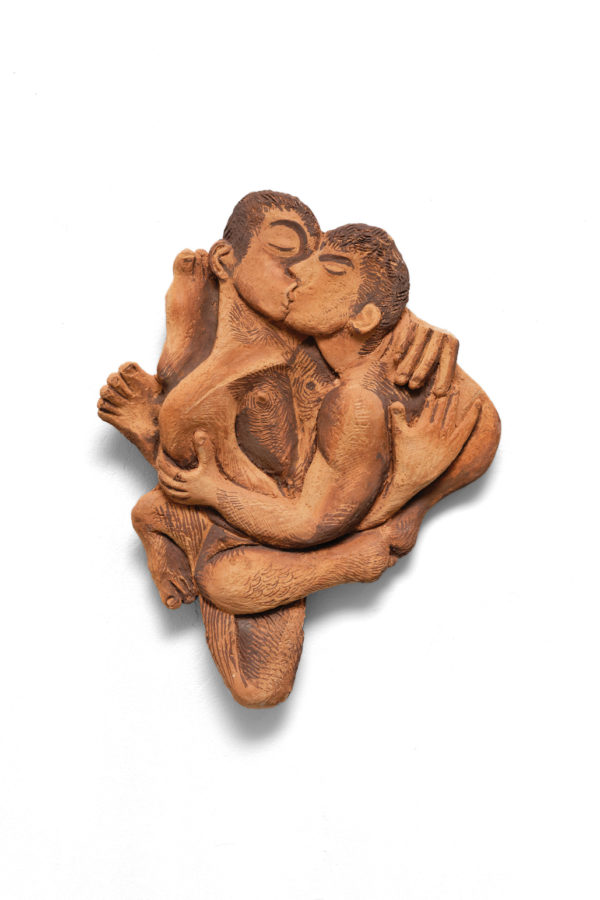

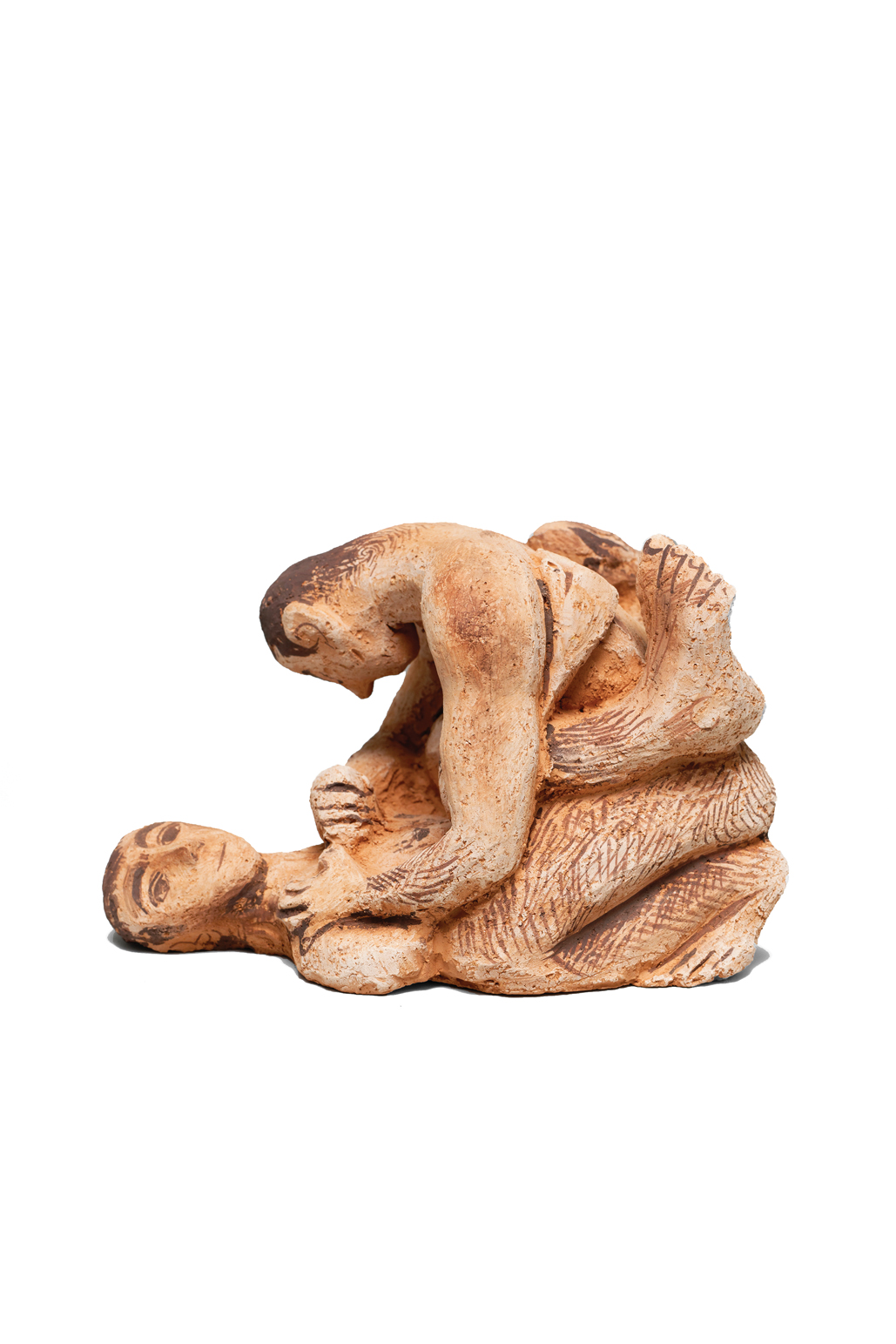

SCULPTURES BY LOUS FRATINO | ALL IMAGES COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND ANTOINE LEVI, PARIS.

LOUIS FRATINO SCULPTURES

In the frosty chill of early 2020, we visited Louis Fratino at the Bushwick studio he shares with his partner, designer Thomas Barger. The open plan was split by the couple’s starkly different styles, the colorful romance of Fratino’s paintings both in conversation and at odds with the puffy and softly spiny architecture of Barger’s furniture. As their dog, Margaret, glowered sharply at us from her roost, the couple welcomed us graciously. With candor and charm, Fratino entertained my inquiry of his recent foray into sculpture and the current landscape of queer figurative painters. Our conversation often returned to the non-linearity of space and time — to the spurious notion of progress and the recognition that art history is not a monolith. After taking notes during our tête-à-tête, I sent him a series of questions.

How does the act of drawing compare to painting or sculpting? Drawing is subconscious and capricious. If art making is about revealing an interior self, then it is drawing that brings me there. Painting or sculpting becomes heavy because it asks to live in our world, which is burdened by rules of perception. Drawing can be anything from a written letter to a hair — it is more free to wander.

When you draw, do you make work from your own perspective, or from a state of astral projection, floating outside of yourself? It depends on the source of the drawing, which ranges from total invention, appropriating other artworks, or photography. When I draw from invention or memory, I am often several feet behind myself — seeing myself and others. I believe that memory and dreams function like that, where we are both in our body and regarding it. When I work from my photography, the vantage point is most similar to my own eyes, sort of like a Joan Semmel painting. Working from art history, I often insert myself or someone I know as the figure depicted, so the perspective is that of the viewer, who is both present and not present in the situations that are depicted.

The concepts of romance and memory are present in your work. You said when you create a drawing or painting, you often “long for a quality of life that doesn’t exist anymore.” Which is more beautiful, the experience or the memory? The memory! For me, when an experience rises up through the surface of memory, the banal and embarrassing moments slide away, or they are made beautiful. So it is likely that the quality of life that I wish for never even existed. I was shocked to learn when reading an interview with Italian sculptor Arturo Martini (born 1889, and a big influence on my ceramic work) that he had exactly the same sentiment — that life had lost texture, that our relationship to the organic or spiritual was threatened by modern living. So it’s never enough!

Part of your style is in the use of a type of face — large, deep-set eyes, a dainty snubbed nose, and small pursed lips. How did this face develop? I remember you saying, “I am the body I live in” when referring to this face. Could you explain? I think that this kind of man is a Frankenstein of art historical interests and self-reference.

I love the type of faces found in classical art history such as encaustic mummy portraits from Roman Egypt, Etruscan smiling terracotta faces, or those painted onto Greek ceramics. These faces are also sometimes representative of an established ideal, so mixed with elements of my own face or the faces I know personally, I glorify my life to the spiritual realm of the ancient world. I think what I meant by “I am the body I live in” was that from a young age, as a drawer of bodies and faces, I was always my first reference.

In your studio you have a mix of high- and low-grade art materials. Do you take pleasure in making skilled and celebrated paintings from cheap materials? I am interested in artworks that feel like a product of magic. Materials like charcoal dust, raw clay, powdered pigment excite me because they feel elemental and humble. When they become artworks, their transformation is more extreme and complete in my mind than those rendered at huge cost by extravagant machines and cold materials.

Are you concerned that by using fragile and non-archival materials, your work may deteriorate? Do you link the ephemerality of materials to your recurring theme of fading memory? I think it is more related to an ethos of experimentation or freedom in the studio. I do not want my decisions to be informed too much by concerns for the longevity of the art object. I feel like a spirit of failure or unselfconscious play is the most productive state to make artwork, and working with these materials encourages that. Also I feel conflicted by the permanence of the art object. I do not really make these works to shout something to the future, but rather as a way to process and enjoy my own life. Anything else is a happy accident.

Can you walk us through the conceptual intention of making small paintings versus making large paintings? Is one more enjoyable than the other? Being that the sculptures you have made are small, would you want to get into making large sculptures? I really love small paintings throughout history. Indian miniature paintings are some of the most exquisite objects ever made in my opinion. And Vermeer who managed to lodge himself in history for eternity, made only around 30 modestly-sized paintings. I love that a small artwork says, “Come closer, look at me delicately, enjoy me privately!” It’s erotic — larger artworks could never say things like that. But I also enjoy pushing myself in both directions. If I make my biggest painting, then I also try to make my smallest painting. Small painting might be thought of as an underdog of recent art history, and in that way it is queer to me because queerness is celebrating alternative or undervalued modes of living. I think because artworks are luxury objects, to make them purposefully less valuable is also a conceptual decision, or an attempt to combat the hyper-commodification of one’s work. But I am curious about all kinds of making and would be excited to make larger sculptures, sets, spaces, or unthinkable things, bearing all this in mind. The important thing for me is to do both simultaneously.

When did your fascination with ceramics begin? My grandmother is a ceramicist and taught ceramics at Gallaudet University in Washington D.C. So I have memories of her studio from a young age, the fine white dust in her studio, pressing shells and leaves into stoneware, the incredibly soft feeling of drying wheel-thrown vessels. I also am attracted to charming things, and the craft-based history of ceramics gives it a household quality that I want to contrast with my subject matter.

How did you get into making terracotta sculpture? Do you think you will continue making ceramic work? I discovered the work of Arturo Martini prior to completing a residency in Albissola, Italy. Albissola is a small town in Liguria, famous for ceramic because it is rich in natural clays and has hosted incredible artists such as Wifredo Lam, Asger Jorn, and Lucio Fontana. Arturo Martini worked in the region, and I used his bas-relief terracotta sculpture as a starting point for the body of work I made while I was there. I do plan to continue making sculpture, and hope to return to that town because I developed some really special friendships with people there who are passionate about ceramics.

Your use of powdered manganese dioxide in a wash allowed you to draw lines of detail on your terracotta sculptures. Was this a way to bring drawing into your sculptural process? It was! I was not satisfied with my abilities as a sculptor and used drawing to cheat curves and points of connection. I was also interested in the strange effect of rendering light on forms that light actually falls on. It works like a double negative, and cancels out the effect of natural light. I think for this reason most contemporary sculpture is not painted in a descriptive manner. I also enjoyed the relationship between decorating the sculpture and the fact that classical sculpture was painted. There is a queerness to the garishness of those painted objects, especially because they fly in the face of the false narrative that the sculptures were white, pristine, and pure.

I noticed one of your sculptures features a bird flying by a skyscraper, a contemporary subject in ancient sculptural style. Are you interested in combining new and old? Yes! I think the idea that time is going forward is not true, and that it’s more like a spiral or soup.

During our studio visit, you mentioned being inspired by filmmakers like Pier Paolo Pasolini and Pedro Almodóvar? How do you process these inspirations? I watch a lot of movies on my laptop and am constantly taking screenshots of stills that I find particularly beautiful. Then I will make drawings from those images until they feel like they are mine, and I insert myself or my boyfriend instead of Antonio Banderas. I think making artworks in this way is also a method of paying homage to these directors as artists, in the same way I reference painters from history.

“Back” (2019).

“Back” (2019).

“Sparrow, skyscraper” (2019).

“Untitled” (2019).

“Untitled” (2019).

“Saturday” (2019).

“Saturday” (2019).

You showed us a short stop-motion animation you made from drawings. Would you enjoy expanding your production to include film? Would you consider photography or printmaking? Dance or performance? Yes! I want to make something with Almodóvar! He is such a great artist. Like food, I will say yes to everything. I also love watching dance. Picasso’s largest painting ever was a set for a ballet, so of course I want to do that too.

You recently have taken a break from social media. What led to this decision? Did you feel a sense of addiction or forced participation? How might it be an obstacle for an artist? I decided to leave social media because I was curious what else I could do with the time I was giving to it. I was definitely addicted to it. We feel really helpless to the whims of social media but actually are in complete control. I was tired of saying so often that I wished it would go away. I think there is something inhuman about Instagram — sometimes it feels very meaningful, other times like you are speaking with a bot. I don’t think it encouraged me to think of every individual I interacted with as a fully complex, real person. So I left! I think it can be dangerous for artists because it rewires the process by which you judge or enjoy making work. It is crucial to be able to make work that no one might see, and Instagram’s far-reaching fingers felt like they touched everything.

Conversely, how do you think artists might benefit from the construction of a persona on Instagram, and what has that experience been for you? I got my first show in New York because the gallerist saw my work on Instagram. It is a really powerful tool that every young artist should take advantage of if they have a healthy relationship to it. It made meeting artists once I moved here very easy. However, I’m not sure if the construction of a persona solely on Instagram is ever beneficial, but could be thought of as an inquiry into the self and experimenting with what you might want to say to a seemingly infinite audience.

How do your paintings and sculptures translate in photos? Do you think the art world suffers or benefits from viewers seeing artwork in photos before seeing or without ever seeing the work in person? I think good artworks always fully reveal themselves in person. Seeing a photo of an artwork is like seeing a photo of a person. It can be misleading. I don’t think the art world suffers for the amount of digital imagery that is circulated. A lot of people don’t have access to artwork physically and seeing it online is a great way to learn about art. Many painters’ work I loved in high school, I never saw in person until much later.

Could you explain your relationship to your gallery owners and collectors? Have you felt any structural pressure to make something or be someone you are not? My relationship with the staff at both of my galleries is one built on trust. There is structural pressure to be something you are not in every moment of life, and I try to make the same decisions in the studio as I do anywhere, which is to be myself.

How is this pressure different than that of your friends or the general public? I think there is a specific kind of pressure on artists, which is to both criticize and entertain society, and that can feel confusing. At this moment my work has been pulled into a current of figuration, so the way in which it’s often interpreted can feel narrow. Overall, I enjoy the luxury of a lot of support from the public and my friends. How is sharing a studio with your boyfriend? Do you prioritize feedback of your work from particular friends in your life? Sharing the studio with Tom is a joy. I enjoy the comfort of peaceful silence with him in the way that I only can with those closest in my life, so we work well together and do not distract each other unless of course I want a distraction. His approach to art making is really different from mine, and I hope that I will be sensible enough to learn from him as I watch him make things. Painting can be incredibly solitary, so it has been a real comfort to have lunch with someone I love every day. Of course I prioritize the feedback of those in my life that I respect the most. But also, if I need some encouragement, I know who to call.

I remember you saying you think there is a notion among some artists and critics that “history doesn’t belong to gay people,” could you elaborate? I think the idea that there are parallel histories — gay history and canonical art history — is not a productive way of thinking about queer people, or history. The fact that it was and still is incredibly dangerous for queer people to exist all over the world does not in any way mean that they did not exist, make work, or function in popular culture. “Gay figuration” is absolutely not a new phenomenon. Sources of inspiration for images of male homosexual desire for me are artists such as Marsden Hartley, Alvin Baltrop, David Hockney, Pavel Tchelitchew, George Platt-Lynes, George Tooker, Jared French, Jean Cocteau, Guglielmo Janni, Charles Demuth, Bhupen Khakhar, Yannis Tsarouchis, Peter Hujar, Duncan Grant, Howard Hodgkin, Filippo De Pisis among hundreds if not thousands of others who very much existed in recent history. I’m not sure I ever heard a critic say “history doesn’t belong to gay people” but I have been criticized for referencing Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Fernand Léger, who some might call figures of hegemonic art history. But these are just some of the characters that I reference, and I, like everyone, am allowed to consume, digest, and enjoy every last bite of these artists!

Have you grown tired of critics comparing your work to Cubism? No, they are right.

You mentioned you feel “we are still processing the questions of the Greeks.” Do you see your work as contributing to a movement already in motion? I feel that it is a little vain to think that we know when chunks of history begin and end. That is a job for the future. So why can’t I feel that Modernist artists are my contemporaries? Many of the issues confronting every generation are still being asked and remain unanswered today. I do not really see my work as part of a movement so much as part of a large family.

Do you subscribe to the concept of “cultural progress?” The idea that because we are the newest people, we must be the most progressive is not true.

How do you feel about the label of “queer art” or “gay art?” I use the word gay to refer to myself more often than not because I pretty much depict my life as a gay man and men having sex with men. I think queer as an umbrella term bears responsibilities of representation that my work currently does not address.

It seems there is a community of queer figurative painters who have gained popularity in the gallery circuit (e.g. the artists featured in Perrotin gallery’s 2019 group show Them). How do you relate to and orient yourself in this community? I am honored to be considered part of such a talented crowd including many of my personal friends, and there is some romance to feel like one is a part of a ‘school’ whether or not any of us might really feel that way.

Do you ever get the sense that you are living in a New York bubble of queerness? Is an intersectionality of the gay rights movement something you consider when making work? Because there is a really high level of discourse in New York, we sometimes forget that the rest of the country or world has a different relationship to queer language or imagery. So yes, New York is absolutely a bubble, but a bubble of many things, not just queerness. A really good thing that came from Instagram was the ease in which young gay people in far away places got to experience my work. I think it means something to those people that it could not to people who live here. In relation to intersectionality, being a painter is kind of like being a one-man show, one in which you usually describe your own experience in the hope that it is a story people will relate to on a human level. But my own experience is just a place to start, and I do feel like I am just getting started. The way we live our lives is illustrated by our work, and I hope that as I get more mature, I will be living more in the service of all people, and hopefully that will be seen and felt in my work.

So is it safe to say that you find the personal is political? Yes baby!

“Tom’s chair”(2019).

“Tom’s chair”(2019).

“Couple”(2019).

“Couple”(2019).

“Dance in shower” (2019).

“Dance in shower” (2019).

Louis Fratino photographed at his studio by Abi Benitez in Brooklyn, NY. January 2020.

Louis Fratino photographed at his studio by Abi Benitez in Brooklyn, NY. January 2020.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 12, get a copy here.