Photography by Matt Lambert

Matt Lambert’s KEIM

I can’t help but remember my shaking hand inching into my best friend’s sleeping bag, advancing with terror and ecstasy. Matt Lambert’s most recent “autobiographical archive,” KEIM, stands on that threshold that separates man and boy, firmly grounded in the contradictions that define “coming of age.” It is soft and hard, confident and self-conscious. Although entirely white, his collection of Berlin boys herein feels quintessentially real; Lambert captures an intimacy that strikes at the trembling heart of exploration, vulnerability, and sex. “It’s sex as a way to kill the boredom, the pain, the angst, the good times and the bad. It’s the normalisation of sex; normcore as opposed to hardcore. It’s the daily, repetitive ritualisation aided by the app or laptop where Grindr or camboys take you into an anonymous, anodyne, often synthetic world.”

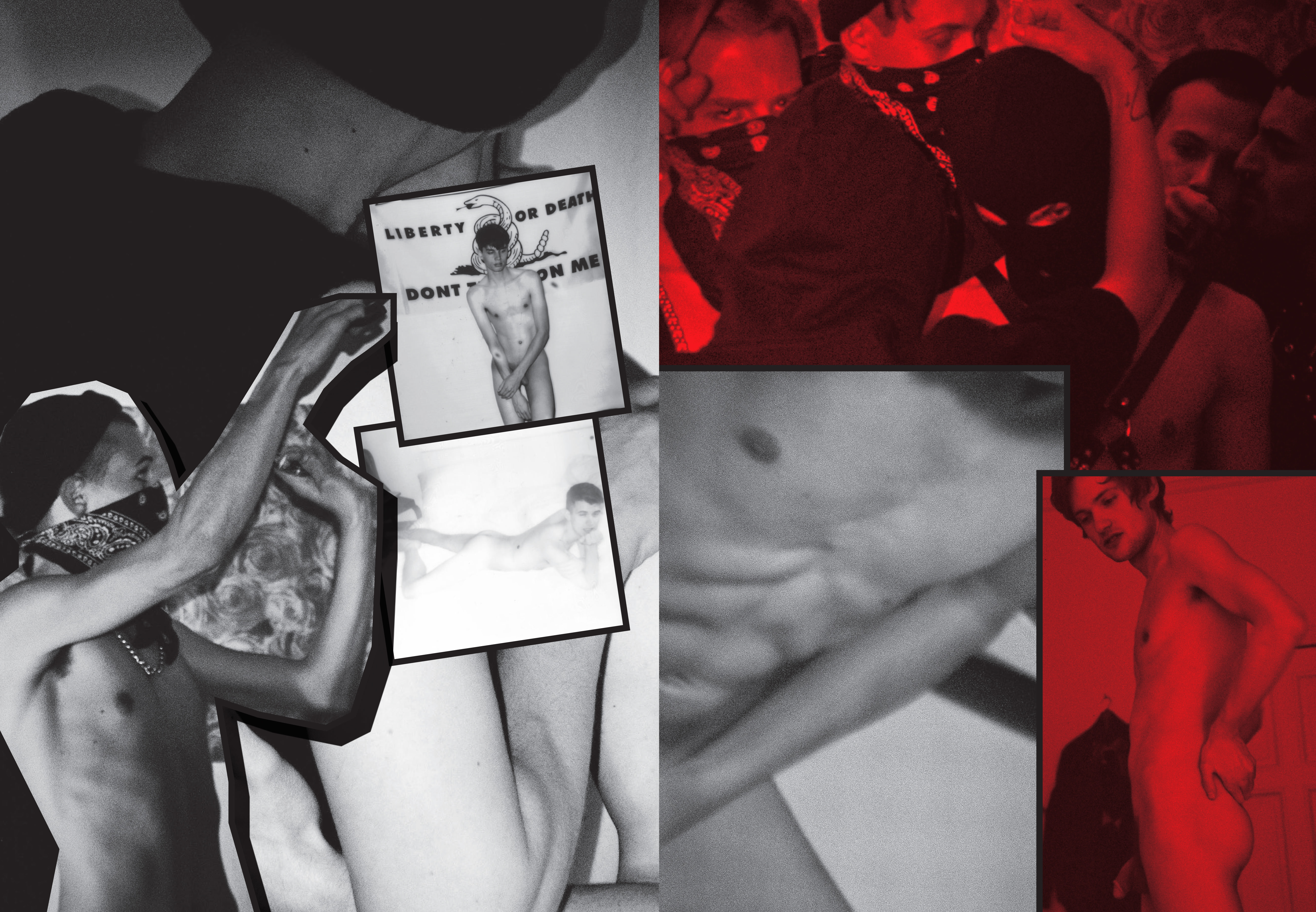

The book contains a zine within the larger narrative, VITIUM CONTRA NATURAM, a momentary departure into the dark, insatiable hunger that boils beneath Lambert’s lighter images. Imagine “Wild child” inscribed on the head of a hard dick. There’s literally a picture of that. The book itself feels curious, pulling you in and pushing you back, teasing your limits. “Keim is a special kind of secret. It’s a book wrapped in whispers, gossip, innuendo, rumor, myth, mystique, mystery.”

We had the pleasure of asking Lambert a couple of questions about his process. Check it out:

How long have you been working on this book? How did it begin? It’s a collection of photos taken between 2011-2014 and mostly in Berlin. As a filmmaker, photography was always an integral part of my creative process. The book is a by-product of spontaneous and intuitive work made during this time, but I never really had the intent to publish them all.

Can you tell us about your process of laying out the book? How do you pair your photographs within spreads to create dialogue between images? This process was a close collaboration between my favorite designers in Berlin, Studio Yukiko, and my publisher at Pogo Books. Since the majority of the book is pure photo and it’s a hefty 168 pages, we were looking for conversations between images and to build humour, movement and strengthen its narrative.

In what type of world do these photographs take place? What realities do you explore? They’re intended to live without time and place, but the underlying presence of Berlin exists in most all the moments. There’s a quiet confidence and open-mindedness people carry in them here that I’ve not found so universally anywhere else. With the exception of the zine within the book, most are intimate moments (not always sexual) that capture the tension before and after the release.

Beyond capturing the actual frames, what would you say your role is in these photos? This varies in every image. I’m almost always present and try to avoid voyeurism. Some are moments of hedonism, others capture a shared intimacy and the rest documents of conversions about life, love and sex — all are honest.

How do you find and choose your subjects? The majority of these images are friends or lovers and the beginning of this series began with Jannis — my first boyfriend in Berlin and now husband. More recently it’s sometimes friends of friends that reach out to me online or me to them. It’s all a pretty fluid reflection of my social life and I rarely shoot models.

The boys are clearly a certain type, young, slim, white, handsome. What else do you look for to know a good subject? How do you gain access to their vulnerability? I feel like my casting reflects a lot of the guys I see in Berlin and there’s something still a bit exotic about them to me. Personality is everything though and I struggle to shoot people who are just pretty. Most the people I shoot are gay and those who represent the spirit of youth in Berlin who are open and ambiguous in their identities. Access is pretty natural and trust through honesty and friendship has been the only way.

In what environments do your best photographs arise? This is pretty wide open, but generally it’s spaces where people feel at home.

How much does your work have to do with “coming of age?” The majority of my film work since living in Berlin explores these themes and I’ve recently completed writing and directing a TV series for a major network in the US that explores coming of age in love and sex. As our notions of self and intimacy evolve parallel to digital spaces, it’s a theme that is rapidly reinventing itself and has continued to stay fresh for me over the past 3 years or so.

Your photos appear to walk a line between intimacy and friendship, exhibition and pornography. How would you define the relationships these boys share? Every image is different and I like to maintain a level of ambiguity as to which of these categories an image falls into.

These boys appear distinctly ‘millennial.’ What is the role of technology in these images? Most everyone in this book is gay or a version of post-sexual-Berlin where fluidity, ambiguity in identity becomes the norm and binary definitions are discussed less and less. Outside of having found a few of them online, digital spaces have definitely played a major role in the ways they expire and define themselves and it feels like there’s an effortlessness and confidence attributed to this.

This collection of work seems to be split into two distinct parts. Why? The middle of the book is called VITIUM CONTRA NATURAM which breaks the monotony of a traditional photo book. It’s a two-color newsprint zine within the book and is part of a larger ongoing project with my husband, Jannis. It’s a throw back to the punk rock scene that first shaped me as a teenager in LA and a collective I was a part of with friends when living in London called BARE BONES.

If you had to pitch this book in a sentence, what would you say? It’s an autobiographical archive of intimate moments that mark the beginning of my film and photography work in Berlin.

Pick up a copy for yourself, the book is available here.