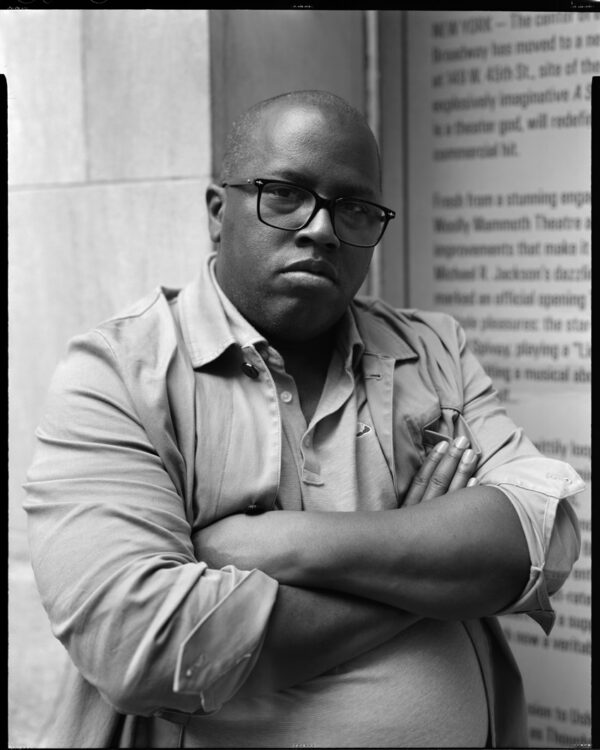

PORTRAITS BY IAN LEWANDOWSKI

Michael R. Jackson

Michael R. Jackson used to work as a Broadway usher mere blocks away from where his new musical, A Strange Loop, is running at the Lyceum Theater. His show, which won the Tony Award for Best Musical and Best Book of a Musical, was in development for 18 years, and what began as a one-person monologue gradually evolved into a full musical production. After garnering rave reviews during its Off-Broadway run at Playwrights Horizons in 2019, winning a Pulitzer for drama in 2020, and attracting a star-studded roster of producers, like Jennifer Hudson, Alan Cumming, and RuPaul (to name a few), A Strange Loop opened on Broadway in April 2022.

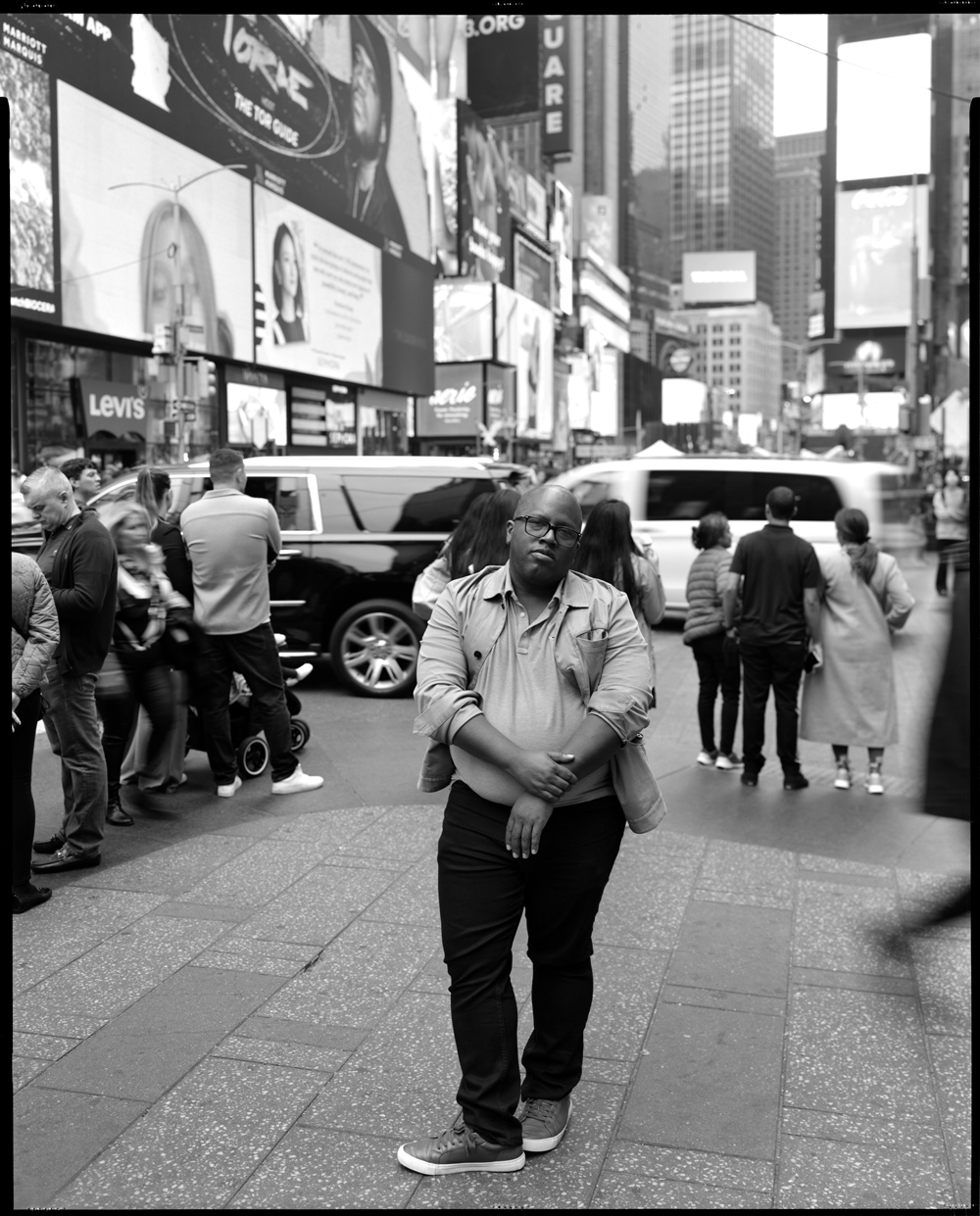

Jackson is from Detroit, Michigan, and came to New York City as an undergrad to study playwriting at NYU. To walk down 7th Avenue with him now is surreal, in part because of the ubiquity of banner ads for A Strange Loop. Look down every single street near Times Square and you’ll see them fluttering overhead, purple and orange, like a fabulous series of sunsets right above the traffic. As we weave around tourists and taxis, I ask if he’s used to the feeling yet of seeing his work celebrated like this, he replies, “used to?” and chuckles to himself.

A Strange Loop is about Usher, a big Black queer Broadway usher who’s about to turn 26. Usher is writing a musical about a Black queer Broadway usher named Usher who’s writing a musical, and finds himself caught in a series of loops born of his own self-perceptions. There are six other actors in the show who portray Usher’s thoughts. They’re ever-morphing, changing costumes and characters, and embodying the ceaseless flow of ideas, worries, fears, and fantasies that plague Usher.

The show is unlike anything else on Broadway, and not only because it features a spectacular, all Black and queer cast. It’s the sort of art that has the potential to reorient your view of the world, and of yourself, precisely because that’s what the show is about: the self. This past May, soon after the Tony nominations were announced, I got to sit down with Jackson and ask him about fame, love, Tyler Perry, and the future.

Michael R. Jackson in Times Square, NYC, May 2022.

Michael R. Jackson in Times Square, NYC, May 2022.

You’ve gone on this huge arc from ushering on Broadway to now having your own show with eleven Tony nominations! What’s changed most in your day-to-day through this whole experience? The thing that’s changed most in my day-to-day is the amount of meetings I have to go to. For press, for getting things ready for the cast album, for different opportunities that come up. It’s quite a lot of that.

You are now part of a lineage of Pulitzer prize-winning meta-musicals. What were you drawn to as a writer about creating a work about itself? I don’t think I set out to do a work that references itself, it’s just that was the mainline to trying to tell this story. I do like meta stories, but I didn’t set out to make one.

In the opening number, the cast sings about the system of commercial theater being “distorted.” You are very up close and personal with this whole system. What are some of the distortions you’re seeing now versus when you worked in theater before? Well, it’s funny because the show has been pretty lauded since it was Off-Broadway, but even as it’s lauded, I can look at some of the praise, and I see that it doesn’t — sometimes the praise, too, feels distorted. Not like undeserved per se, but sometimes the way people praise the show, which comes from their own perspective, is totally different from how I see the show. So that’s this weird thing, and it kind of mirrors the negative portrayals as well. For example, I made it a point to invite a conservative reviewer from The National Review and of course he came and he hated it, but the things that he said were so — for me, had nothing to do with anything that I’m doing. And it was a Black gay conservative critic. And the headline said that I was doing critical race theater. He then went into all those things about that, which again, have nothing to do with anything really in the musical, but it’s the lens through which this person saw the show.

On the flip side, there were reviewers praising it saying that I was an activist who wrote an intersectional musical. So what am I to make of that? On the one hand I’ve got CRT, liberal blah blah blah, and on the other side I’ve got that I’m an intersectional activist writing musicals to: fill in the blank. And at a certain point I have to divorce myself from all of it because that’s how these folks see it. And I’m not necessarily even making a real judgment on their analysis, but they’re coming at my show with a worldview, and so therein lies the jenga.

The cognitive science theory of the strange loop, that one’s sense of self is abstracted from thoughts which are also self-generated, can apply to anyone, but do you think that these loops get stranger the more one is othered by society, like Usher? I do, but I also think that itself becomes another loop that’s inside. There are these expectations that may come from the outside, but when you internalize the external, it starts a feedback loop. So I find, in my own life, that I have to be conscious of what I have internalized and what is external that I can respond to.

In your interview with The New York Times Magazine you spoke a bit about your relationship with Tyler Perry, who you text casually. The show reads him and his work for filth at times. Well, can I ask you a question about that?

Please. This is something that I have really been thinking about. Like, does it read him for filth or does it read him the artist?

I think the latter. I think it’s easy to seem like it’s him, the person, because your art is so who you are, and even in

A Strange Loop, art and personhood is like one thing for Usher, so maybe that is true for someone like Tyler Perry. I don’t have his strange loop, so I can’t say how he looks at it.

It’s an important distinction. Even Usher says that he doesn’t hate Tyler, he just thinks that his work — is bad.

Is bad. Has he seen the show? He has not. He’s definitely aware of it. I know that he has at least listened to the song “Tyler Perry Write Real Life.” What he thinks of it, I do not know. So the ball is in his court.

Did you hear at all from Todrick Hall, who also gets referenced onstage, after he saw the show? I didn’t! I just saw that he did an Instagram story about it.

He was there at the performance I saw. Did you see him?

I was a few rows behind him. Oh my god! What was he like?

I think he was gagged at that moment his name came up. He said something to the people sitting with him, which I obviously didn’t hear. Probably, “Who the fuck is you, nigga? Who the fuck is you, nigga?!” Did he clap during “AIDS Is God’s Punishment?”

I don’t think so, but I can’t say with certainty. That is another great moment. To see who claps. That’s the game of that.

It’s fascinating. Can you talk about the live experience and the audience’s involvement in the show? So for me, the audience is the seventh thought, and so I invite them to react with total authenticity. I want nothing but authentic reactions from them. Though, what’s fun about that is because the show is speaking to many different people, at different times, in many different ways, a part of that seventh thought is turning to your neighbor to see — you’re commiserating with them, being mad at them, not understanding them, whatever, all of it. And that’s because you’re in Usher’s mind. You’re seeing things as he’s seeing things. And when that moment comes up you have to decide yourself how you want to react to it, and that causes a feedback loop. The stage is coming to the audience, the audience is feeling loops within loops that go back to the stage and then come back again. And that’s why it’s one of the most exciting moments of the show because it really invites the audience to participate and energize the loop that Usher is stuck in.

Who would you most like to see this show? I would really like for a group of pastors to come see it, like Baptists or COGIC [Church of God in Christ] pastors to come see it.

What is it like now dating as a public figure? Are you still able to use the dating apps like before, if you’re on them? Well, I didn’t really do it before. The truth of it is, I’ve been saying I’m a career gal. I’m on the apps, but I never go on the apps. I have them on my phone, but I’m never on them because it’s the same struggle I’ve always had with them of not really knowing how to navigate them successfully. Something I’m needing to work on is being more forthright about what I’m looking for. But even when I start to think about that, the apps seem like the wrong place to go. So I’m not dating anyone at the moment. I was kind of seeing somebody right before the pandemic started but then he ghosted me, and I sort of realized in that moment the profile of the sort of person who I needed to be involved with. But then in the racial reckoning, the pandemic, the super polarization of this country, it’s actually making me reevaluate who I’d be involved with again. The thing I’ve learned about myself during this moment is that I’m a sort of small-L libertarian in the sense that I’m a very live and let live person, and I need to be with somebody who is also a live and let live person, and we are not living in live and let live times, in my view. So I’m always trying to figure out where people are coming from because you just never know who you’re talking to until you really get to talk to them. And I just want an authentic, intimate relationship with whatever man I’m with, and I’m finding it difficult to vet for that. But I’m interested. But where he at? Where he at? I know where I’m at, but where he at?

Where are you happiest? I’m happiest with friends who I can speak freely and openly with, and who I can be truthful and real with.

Can you tell us about the horror film you’re working on? It’s still coming together but it’s basically me confronting a fear that I identified during the summer of 2020 about people. Groups of people. And wanting to investigate that fear. Fear of a group mentality. A fear of people who think they’re all doing the right thing with a hundred percent certainty. And what happens when those people really go too far.

Of all the accolades that the show has received so far, what’s been especially meaningful or memorable for you? I think watching my director, lighting designer, sound designer, set designer, the cast members, the orchestrator, my boosters, to see them being nominated for a Tony. Because we’ve put in so many hours of work over so many years, and agonizing moments trying to get the show right, to see that many people in the company acknowledged in that way, there’s nothing better.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here.