PHOTOGRAPHY BY CONNOR ATKINS

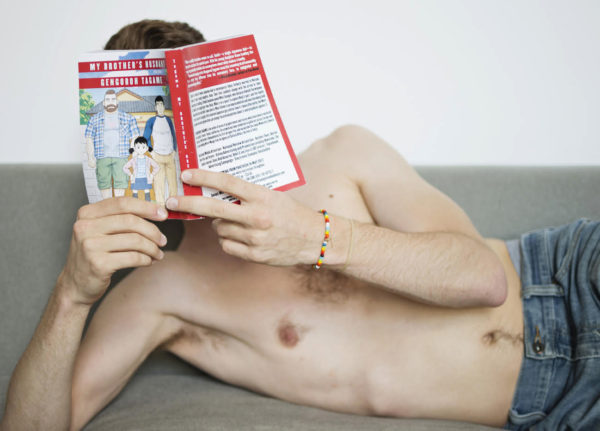

My Brother’s Husband

Gengoroh Tagame's new graphic novel explores old prejudices

Gengoroh Tagame’s manga My Brother’s Husband marks a dramatic shift from the artist’s other work. Tagame has been a fixture in the Queer Japanese BDSM fetish community since the 1980s and has been published in numerous publications and collections. He often sites Bill Ward, the British gay BDSM erotica artist as a major influence and his work is often compared to Tom of Finland’s illustrations due to their hyper-masculine beefy builds.

My Brother’s Husband follows Yaichi, a heterosexual single father whose gay twin brother, Ryoji, left Japan in his early twenties in search of a more accepting home. After Ryoji’s death, his husband – a Canadian named Mike Flanagan – travels to Japan to connect with Ryoji’s family and explore his childhood home. Yaichi, a deeply homophobic man, learns to empathize with Mike and posthumously accept his late-brother through the eyes of his young daughter Kana, not yet affected by the prejudices of her father or larger Japanese culture. While the story Tagame weaves is both touching and effective, it makes far more sense aimed at a Japanese audience than an American one. Japanese culture has an ingrained homophobia that Tagame himself mentions in an interview with Vice, saying “there was no term ‘same-sex marriage’ when I started to write My Brother’s Husband”. While there are many American readers who would benefit immensely from reading the manga (i.e. the 37% of Americans that still oppose gay marriage), the market the novel seems to be aimed at is gay Americans in their late-teens. These readers may have already read or experienced stories similar to that of My Brother’s Husband and one might suspect that they’re ready to move on to more complex, less compartmentalized examinations of queer life.

In My Brother’s Husband, Tagame seeks to appeal to a much broader audience, specifically a straight one. In Japan, the manga was originally serialized in a hetero-focused publication called Monthly Action Comics, which given Japan’s widespread homophobia is itself a feat. Unfortunately, what made Tagame’s series so well-received in Japan makes it feel largely superfluous in the United States. In Japan, its inclusion in a heterosexual-serving magazine displayed an impressive progression in the social perceptions of homosexuality. In the US, where a variety of complex gay narratives are beginning to be displayed in all forms of media, the story feels a little behind the times. While we still have an incredibly long way to go, Tagame’s work isn’t doing anything that hasn’t already been done before, making it feel somewhat redundant to a modern climate that requires queer narratives to push cultural boundaries.

Despite the fact that My Brother’s Husband is not telling a new story, it’s at least telling its story well. One of Tagme’s most interesting techniques is his way of representing the clash between Yaichi’s homophobia and his desire to appear respectful. Often when Yaichi sees Mike say or do something that either references his sexuality or reminds Yaichi that Mike is gay, Tagame will show Yaichi imaging his visceral homophobic reaction and then show the actual tempered attempt at civility Yaichi makes. While Yaichi experiences overarching development he does escape his prejudices all at once. Tagame manages to depict a very tangible emotional change that includes both progress and remission in his protagonist.

Ultimately, the story is about Japan. Tagame seeks to represent both Japan’s difficult relationship with homosexuality and Japan’s generally restrictive culture. Through the eyes of Kana, readers see a variety of problems Japan still has not confronted. Tagame uses Kana as a hopeful voice for the future, showing that the homosexual-prejudices that dictate much of Japanese society do not have to continue as long as the next generation is taught to be more accepting and inclusive. This goal makes the graphic novel important and effective, but also shrinks its large-scale appeal. So much of Tagame’s focus is on Japanese-centric problems that many American readers not familiar with manga may fail to benefit from the novels true message.