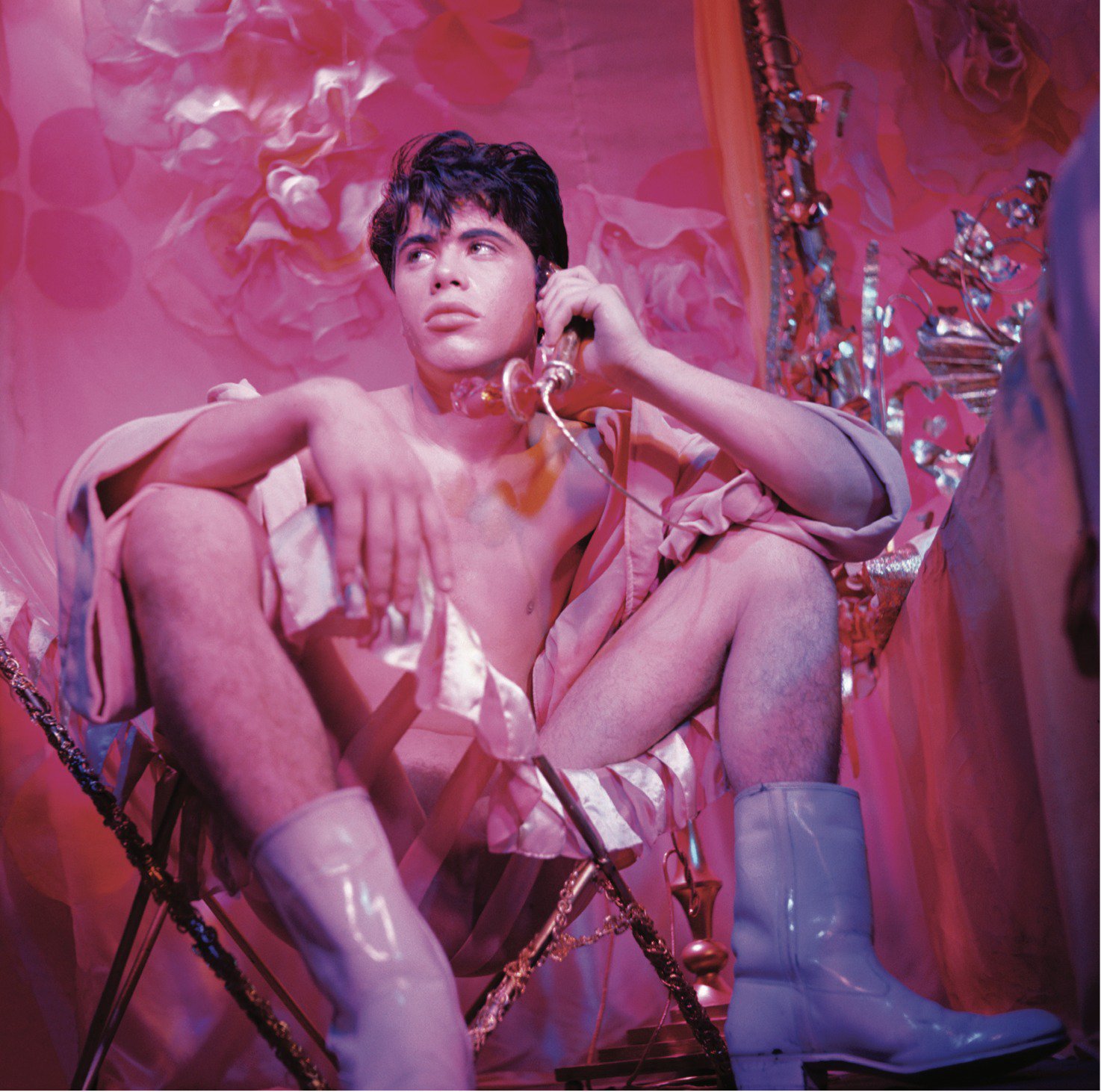

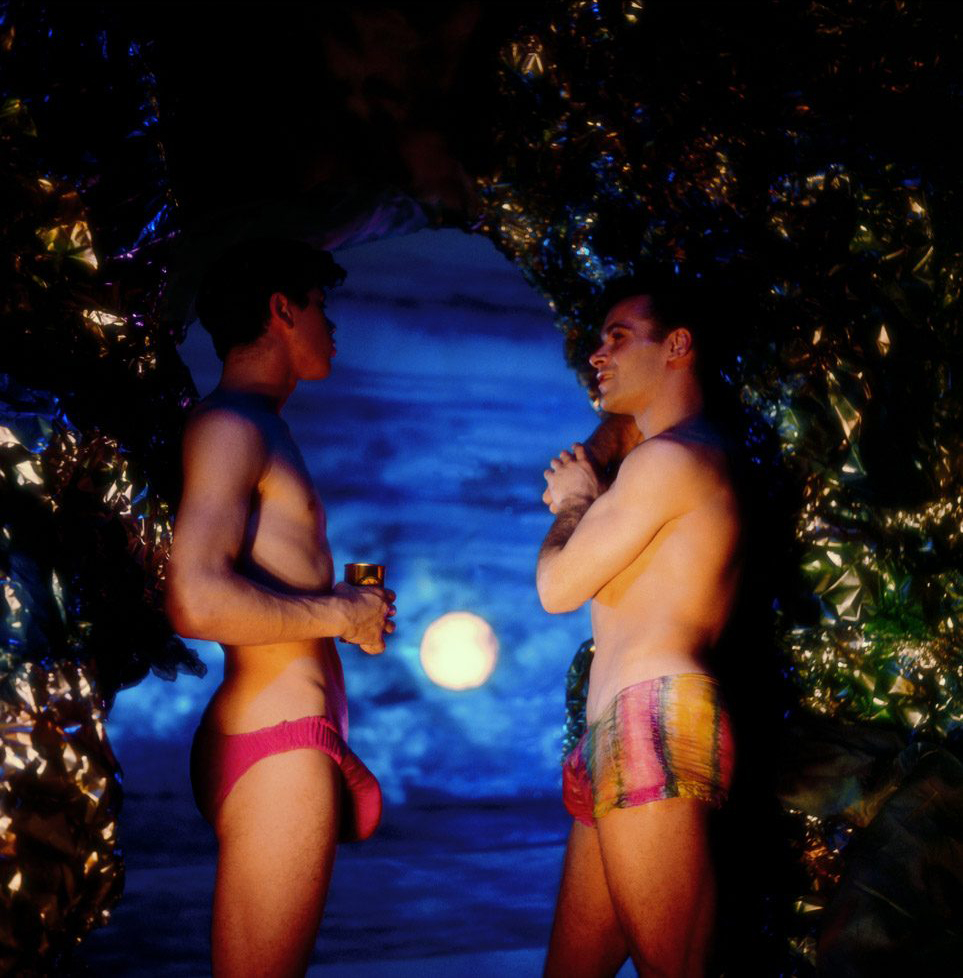

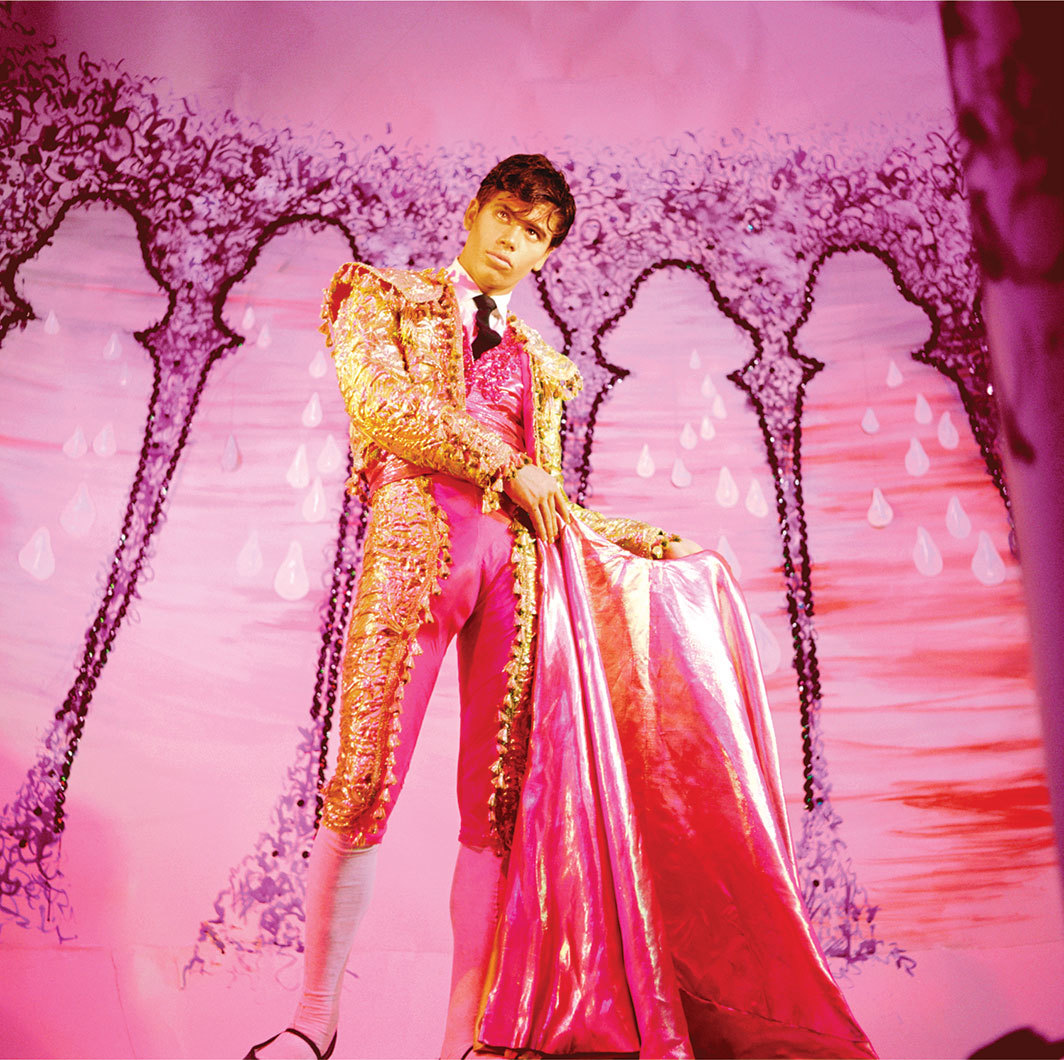

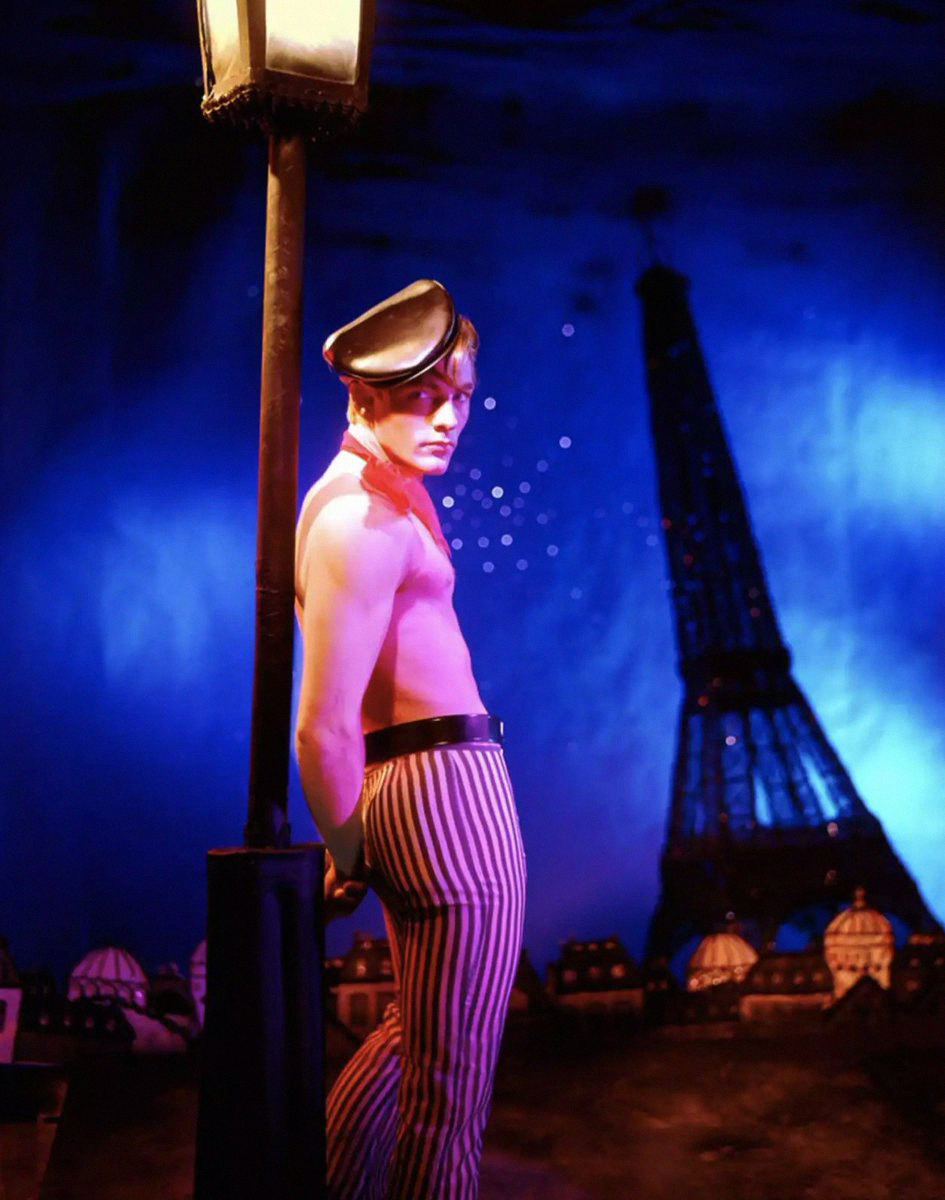

All images by James Bidgood — courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York City.

Out of a Dream: James Bidgood

When I first arrived at James Bidgood’s West Village apartment, I watched him tear open an envelope and read an eviction notice.

“Oh, fuck!” He told me. “Well, I apologize. I might be a bit distracted today. I’m not really sure what’s happening here.”

I nodded and told him to take his time and make whatever phone calls he needed while I found a spot for my jacket and backpack. Looking around the tiny apartment, I couldn’t imagine how he’d ever move everything out of this cramped space if he were indeed forced to leave. Shelves were packed with boxes, bags lined the walls and reached the ceiling. Glitter covered the floor, and a large plywood table littered with bits of paper and chiffon bisected the room. No idea where he slept.

“It’s a mess in here because we were shooting. I can’t find my dust pan, so what good would it do to sweep?”

Nearly all the images Bidgood created of beautiful boys swimming in shimmering lagoons, laying in flowers beneath a pink sunrise or standing in front of the Eiffel Tower were photographed in a space similar to the one I had just entered. It was Bidgood’s wild imagination and abilities to trick both the camera and the viewer that made these photographs seem so surreal.

I thought about the whimsical, ethereal paradises he created in his past work, most notably in his watercolors and in his 1971 film Pink Narcissus, and how terribly far that world is from his present reality.

“OK. I’m ready for you. I just have to answer my phone if it rings.”

My first question for you is just to ask for a bit of your background — where you grew up and how you eventually became an artist in Manhattan. Well, my first question to you is why the hell don’t you know that? Tell me what you know. Too often, little twinkies — is that what they’re called? Ah, no, twinks! A lot of the time, twinks like you come in for these interviews and haven’t done any research. There’s about 8 billion articles about me on the internet. I love reading them because I learn a lot of stuff about me.

I read some of them and learned a lot of stuff about you, too, but I want to hear your story directly from you. Fine then. I was born in Madison, Wisconsin. But who cares? Madison was a nice place. What I didn’t know about it at the time was that Life magazine had named it one of the best places in the country to raise a child. And it was actually a pretty liberal place. Of course, there was bigotry, but it wasn’t outright and there weren’t any incidents or ugliness. So I had a good start, so to speak, about being gay.

What were your creative outlets in Madison? What did you like to do? I was the town’s prima donna, I’d like to think, and I was a terrible at tart. I was unusual — I don’t think there were many naughty boys like me. But aside from that, I was in school musicals and plays and theater. So I moved to New York.

Tell me about your early days in Manhattan as a drag performer. At fist, I was in an off-off-off-off-Broadway show called Dakota, which was amazingly original musical, since the big show on Broadway was Oklahoma. It was rather derivative, to say the least. We had to go out on the street before the show with tambourines and hustle customers like we were in some carnival freak show. “Step right up, ladies and gentlemen!”

Anyway, I was homeless in the Village, but I was 18 years old with tight Levi’s, so I found places to sleep. While I was looking for a bed one night, I stopped in at this bar where I’d seen all these quirky drag queens. Oh, they were fabulous. Some of them were queens in rags who had no home — like sort of gay hobos. They are how I heard about drag. So I bought a yard of gold lamé and stitched up a dress. I did some small Sunday afternoon shows and Carol Channing impersonations, and someone told me I should audition for Club 82. I did, they hire me, and I worked there for a long time on sets and costumes.

How did you transition out of that and into photographing men? I would look at Playboy and see photographs of naked woman all coiffed and done up, looking absolutely gorgeous! The production of those shoots was so spectacular it could have been Vanity Fair if they’d had their legs closed. But for gay men, the only nude photos were of some nasty little boy standing by someone’s mantle, and they were all really tacky and tawdry with no color and no lighting. I wanted to do something unusual.

Your photos of these boys are just so pretty. What made them sparkle? When I was very young, I liked to sit on the curb where cars would park and leak oil into the water that collected in the gutter. These oil slicks created the most amazing rainbows and iridescent colors, and I would look at them for hours. It just fascinated me.

So, I added boys to that idea to create these photos. There’s a painter I like a lot — I can’t remember his name — but he used nymphs and baroque settings, and I was very drawn to that. But most of my imagery just comes from my head.

Bobby Kendall is the model for a lot of your photos and the lead in almost every frame in Pink Narcissus. What about him is so captivating? His soul and his spirit. Or at least that is what it was to me. He’s a very pretty boy, although he thought he looked like a monkey. Bobby was straight, actually, and was a terrible hustler. He was too nice and was awkward about accepting money. In front of the camera, he adjusted fine, though. I think it was readjusting back to reality after a shoot that was difficult for him. He had stumbled into fairyland and all the fairies were gasping and going gaga over him. I think he liked that.

Why are you so drawn to the color pink? Well, I’m not anymore.

Why not? Because that was a period I went through. Pink is a Follies color, and I was very into that at the time. Ziegfeld was always demanding more pink light because it made the skin look more sumptuous, I guess, but I also used lots of blue and orange, specially in my underwater shots.

There was also a film called Black Narcissus, so I think when I had combined the idea of pinkness with boys, it seemed to fit for Pink Narcissus. As I’m sure you know, that was the work that was completely taken away from me after I spent nearly a decade working on it.

What became of your latest work with Christian Louboutin? Louboutin is a lovely man. I did one photograph with him, and he wanted me to help art direct a book he was working on. But the publishers — French, of course — didn’t want an American working on the book. Especially not one who took gay, quasi-pornographic, erotic photos, Christian liked what I did, but I was eventually phased out of the project altogether by one of the French editors. That’s been the story of my life with practically everything — either they’ve taken it away from me four months before it’s finished, after I’ve worked on it for seven years, or I get aced out by some French prick.

So what do you do with your ideas when they’re not recognized in the way you feel they deserve? Forgive me, but I am a talent, and I have an awesome imagination and a thousand ideas everyday. I have a box full of drawings that are never going to be anything more than ideas. I used to burn myself with matches whenever I had an idea, to try and stop myself from having another idea. Because it was so painful — more painful than the match — to know I could never fully realize any of these things. Even though I knew they were wonderful.

What makes you happy? Only two things have ever made me happy. One was being in love with my soul mate, Alan Blair, who died after we were together for 10 years. It wasn’t just a passing affair — we were deeply in love. Two people couldn’t fit more deeply into a pod than us. We were wonderful together, and I worshipped him. He died of brain hemorrhage in 1985 and it killed me for years. For 20 years after, I would take out his picture and talk to him and weep. It’s only in the last decade that I’ve stopped doing that. Still, that’s a lot of time to get over someone, and I’m still not really over him. He was the best person ever.

The only other thing besides Alan is my work. It’s all I do all day. I get up early in the morning and I do some projects or start a new project. Sometimes I forget to eat all day, and sometimes I don’t notice that I’ls gotten dark outside.

You’ve got an Idiegogo campaign for new supplies and materials. How are you hoping this will move you forward? My mind has always being Hollywood, but my pockets have been a cabaret show or something you’d put on in a backyard. I never have the money to fit my mind. I think in billions of dollars, and I don’t have it.

It’s very easy to replace memory with something that’s not real. I became so deeply involved with my work that I’ve confused what has really happened with what I’ve imagined. It’s easy to lose track of the truth.

I am very poor, and I am very unhappy.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 2.