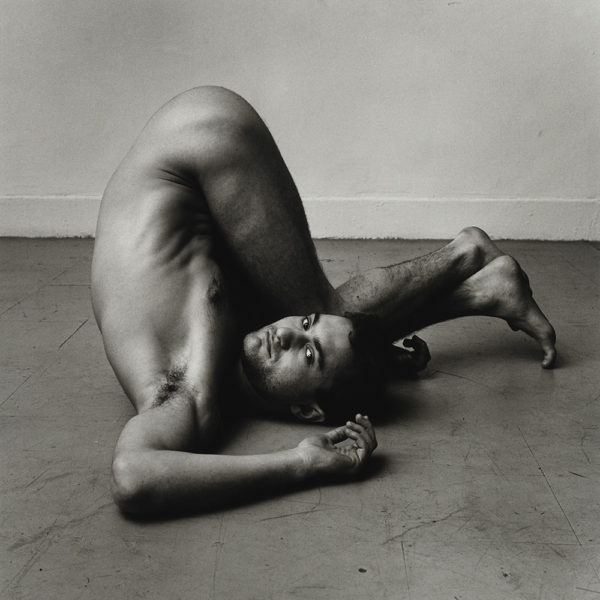

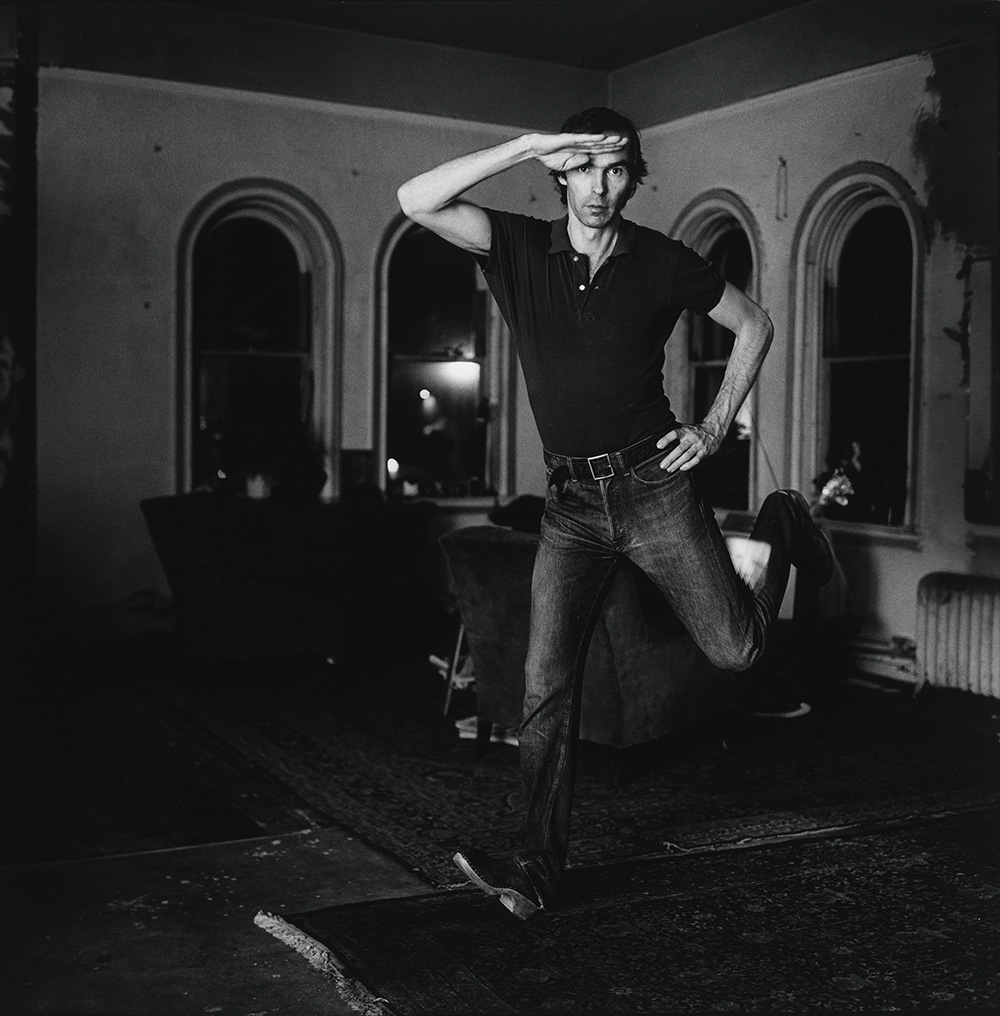

Gary in Contortion (2), 1979. Photography by Peter Hujar. Courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum.

Peter Hujar: Speed of Life

A timely show at the Morgan marks the late photographer's raw talent.

Peter Hujar: Speed of Life, now on view at the Morgan Library and Museum, confirmed what I already knew about the late photographer Peter Hujar and taught me a lot more. In 2013, the Morgan became a repository of Hujar’s collection, including 100 photographs, his correspondence, other ephemera, and over 5,700 contact sheets from publications. 160 photographs are exhibited in Speed of Life — curated by Joel Smith — from private collections and the Morgan’s recent acquisition.

The opening text explains Hujar was nearly penniless when he was photographing, that he died of AIDS related pneumonia on Thanksgiving Day 1987, and was famously intertwined with the East Village luminary David Wojnarowicz. (Wojnarowicz created now iconic photographs of Hujar immediately following his death, but as my friend noted, “Isn’t it a little sad their names might never be found without the other?”) It’s good that this canonized information gets out of the way early because Hujar’s work doesn’t appear to be hung up on anything autobiographical. Speed of Life is a competent introduction to the artist and his many approaches to making images.

It’s very easy to step into Hujar’s eye. He doesn’t introduce any profound themes in his photographs; Hujar was an artist not in search of any great answer but perhaps just was prone to feeding that capricious thing called inspiration. Though his style and subjects are not necessarily the most discerned (save his uniform, square compositions), I admired his amalgam of interests — it seemed genuine, like photography was obviously something he was born to pursue. Speed of Life opens with a self-portrait and delves into a breadth of subjects that Hujar took a liking to, which include animals in repose, lucidly-framed landscapes, performers readying themselves, and of course, men.

Where it is clearly easy to place Hujar into a social-sphere, it’s much more difficult to say just what exactly makes a Hujar photograph. He’s not a landscape artist, and he’s not a documentarian – though he’s talented at both styles. What is for certain is his control over light. He had a special knack for capturing the more decadent tones of back-lit photographs. Alas, like Robert Mapplethorpe, Alvin Baltrop, and Nan Goldin, Hujar had the proper technical chops to make institutionally valued work. These photographers – all in conversation with one another – spearheaded styles within post-modern portraiture, but institutions are prone to compartmentalizing their work; they struggle to call the content of the work anything beyond “outsider” or “gay.”

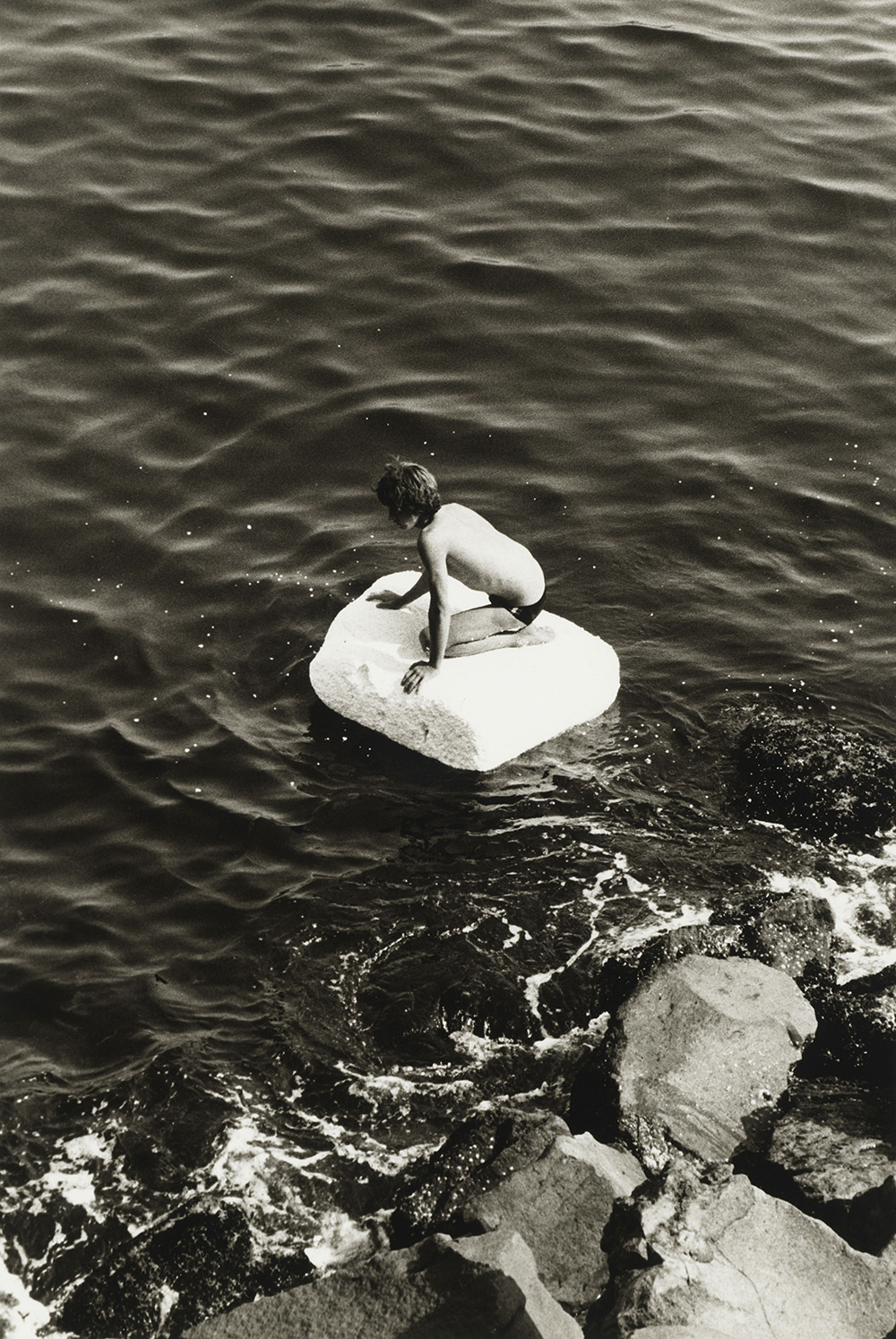

Boy on Raft, 1978.

Boy on Raft, 1978.

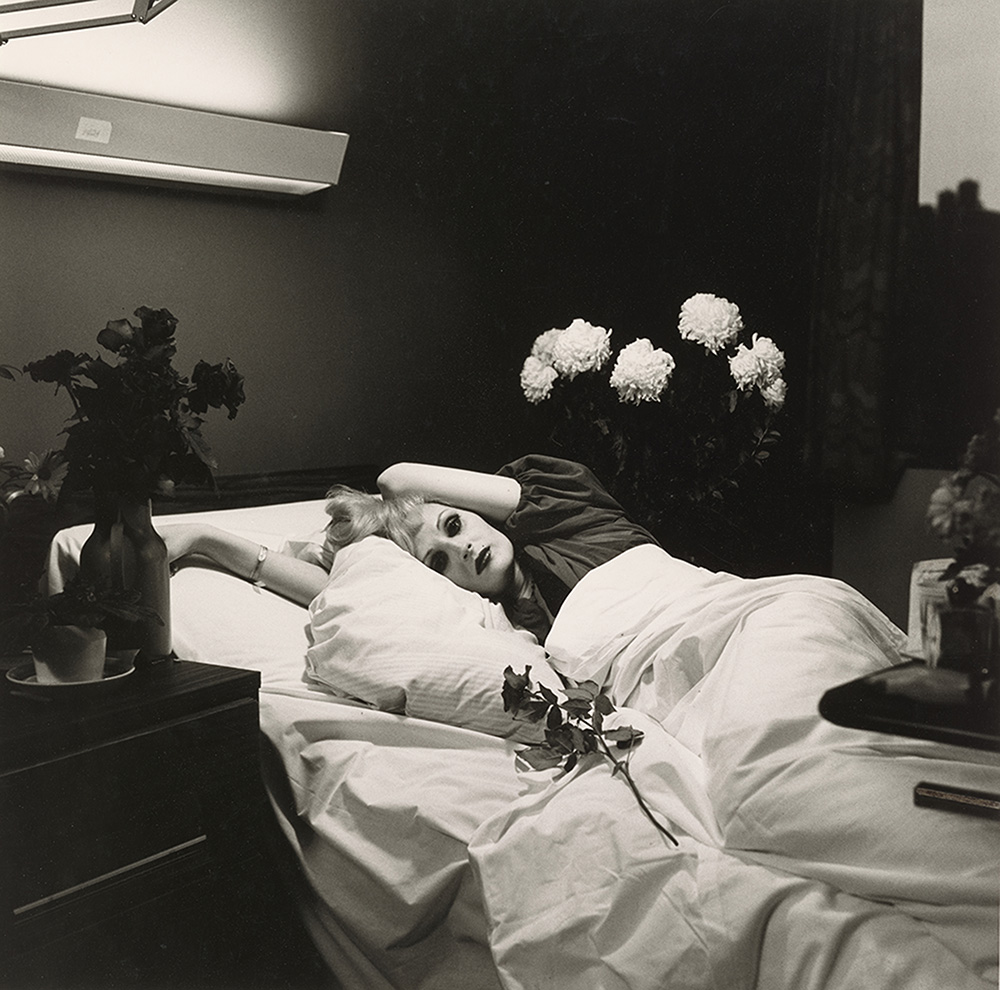

Candy Darling on her Deathbed, 1973.

Candy Darling on her Deathbed, 1973.

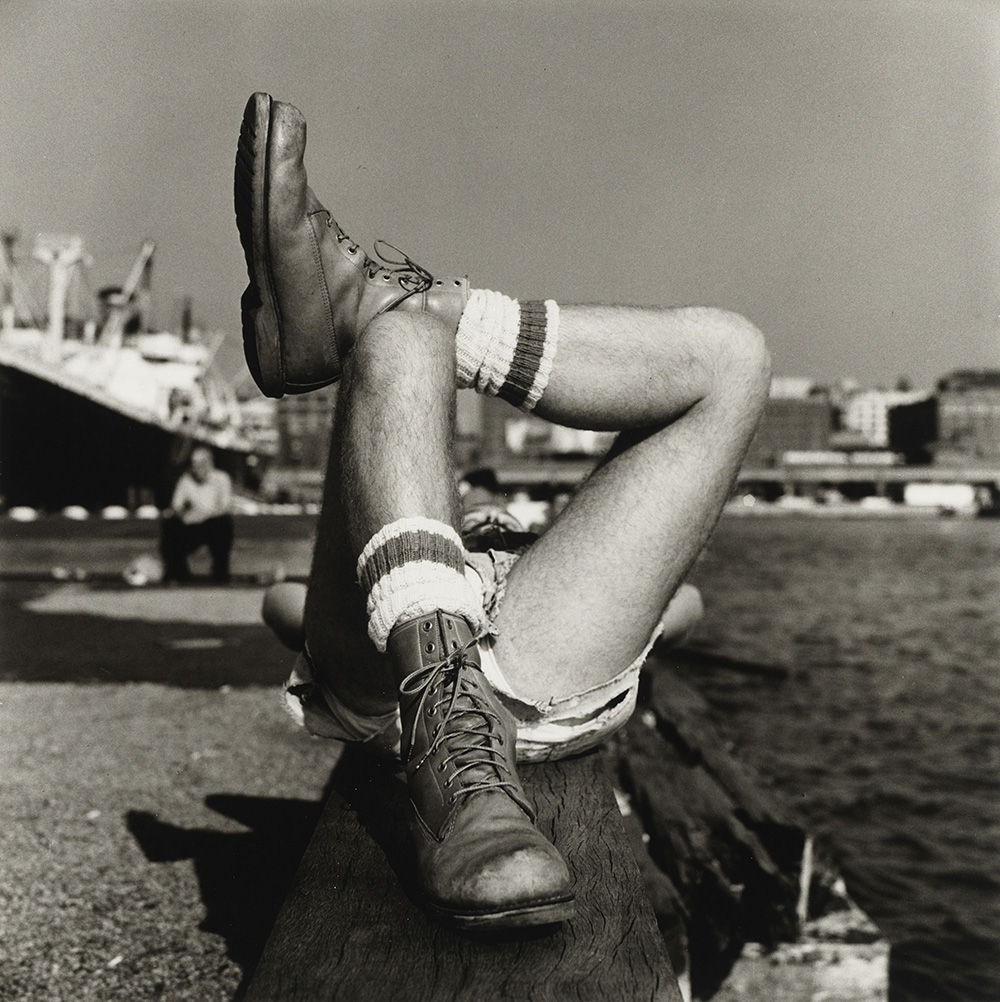

Christopher Street Pier (2), 1976.

Christopher Street Pier (2), 1976.

Dog, Westtown, New York, 1978.

Dog, Westtown, New York, 1978.

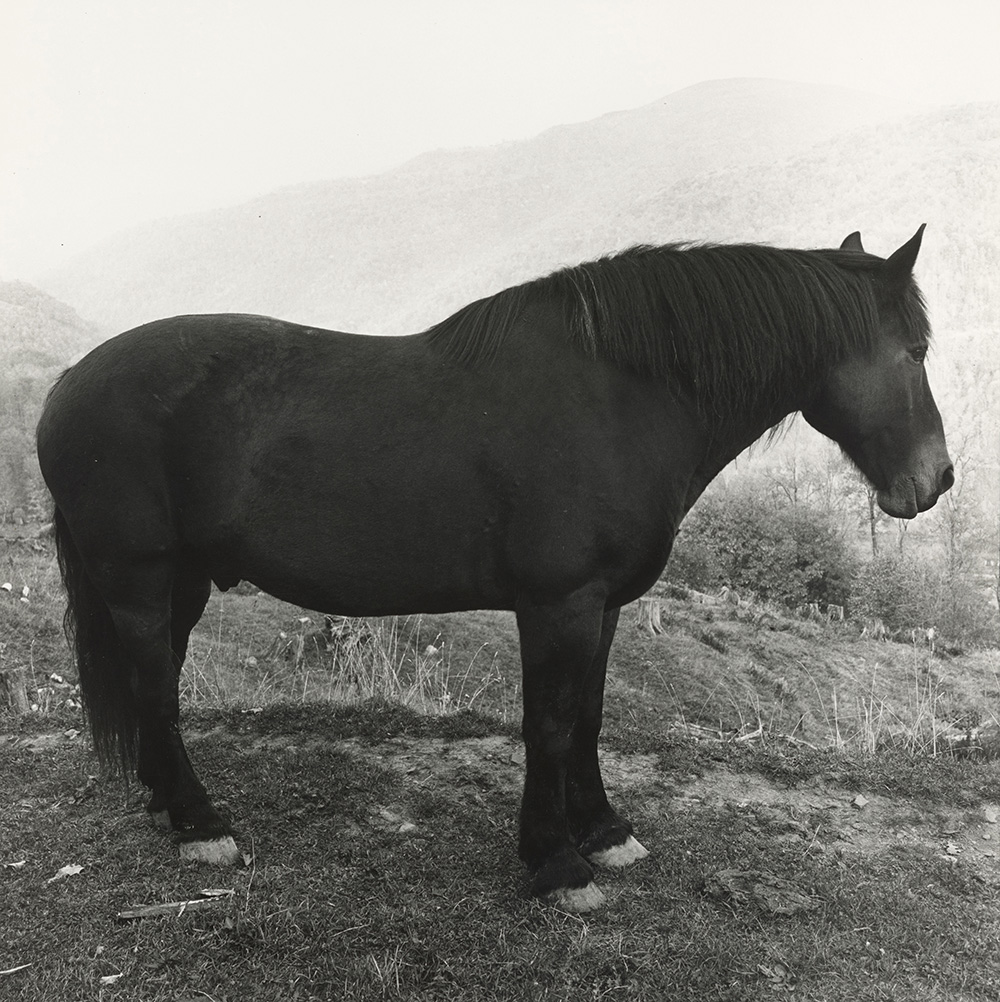

So what is it about Speed of Life that is so transcendent? For one, it’s timely. We’re at a point where nearly every major institution is climbing the pole toward retribution, and the Morgan is joining the ranks. (Upstairs is Tennesse Williams: No Refuge but Writing, and the first Friday in March offered a screening of Pink Flamingo. Fabulous programming.) The works chosen for exhibit also proves that Hujar has influenced countless gay photographers working today. I immediately saw Gerardo Vizmanos in his figuration, and Ryan McGinley’s “Animals” has some Hujar flavor too. Both McGinley and Hujar seemed to be interested in how animals influence human comfort, and how moments of momentum are easily turned serene.

Many magazines would not commission Hujar, and a museum representative on my tour mused this was perhaps a reason for his lack of fame. This past weekend, in what is being considered a monumental moment for gay men in media, four gay actors – Zachary Quinto, Matt Bomer, Andrew Rannells and Jim Parsons – posed for the cover story of T Magazine. As I made up my own opinions about the cover, shot by Inez & Vinoodh, I could only think of Hujar who explored the group image himself. In one of the Morgan’s brilliant curatorial choices, a group photo by Hujar spans from a large gathering of friends plucked from an after party, to group portraits of his closest friends, to harrowing images of corpses taken during his excursion to the French catacombs.

I appreciate Hujar’s ability to speak the language of fashion and sex, and I would kill to dig into the contact-sheet archives. Speed of Life shows us a photographer trying to focus on his imagery in a world that wasn’t interested in focusing on him. After seeing the exhibition, I recognize Hujar was photographing as a claim to authority over his autobiography, which is why the opening text feels so scrutinized, and born out of language hetero-normative institutions have designed to make gay art palatable for the masses. AIDS happened, and I’m not suggesting we forget it or take it out of the show’s catalog. However, I have begun to wonder how curators, especially gay ones, can talk about these artists without pigeonholing them or making assumptions by forcing their work into a biographical context. Was it totally necessary to mention he was “penniless”? I guess one could always exercise the point, but in no way did Hujar’s economic situation affect the quality and bravado of his work. I would argue it is necessary to mention his AIDS-related death, but then we should probably tell the viewer that Candy Darling, David Wojnarowicz, and the countless gay men Hujar on exhibition died of the plague too. AIDS was not subtle, but its incorporation into the biography is, and that doesn’t bode well with me. In the present-day context of American politics – not far off from the administration in 1981 – we’re probably better off screaming that he and his friends suffered from ignored deaths rather than just casually mentioning it.

Are we defined only by what has destroyed us? Speed of Life shows otherwise.

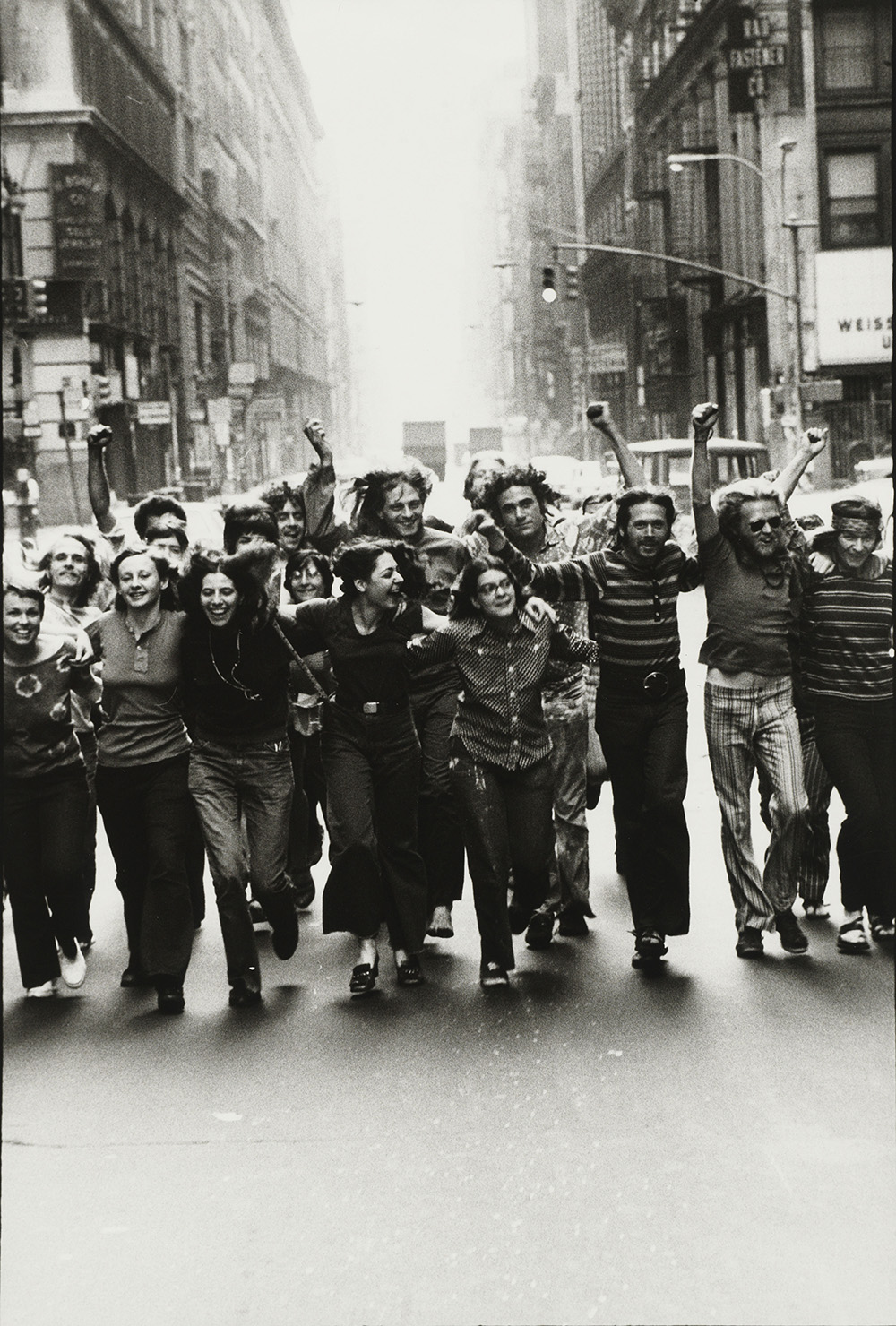

Gay Liberation Front Poster Image, 1969.

Gay Liberation Front Poster Image, 1969.

Gary Indiana Veiled, 1981.

Gary Indiana Veiled, 1981.

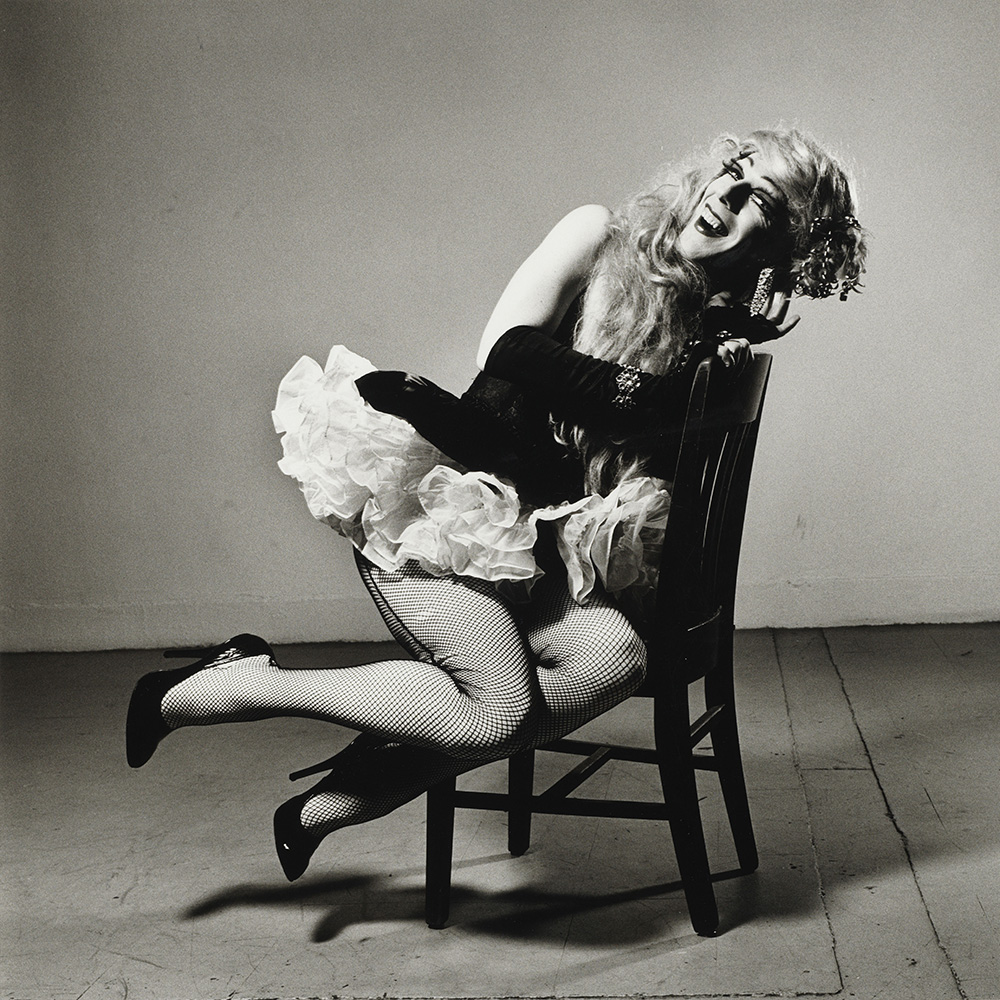

Ethyl Eichelberger as Minnie the Maid, 1981.

Ethyl Eichelberger as Minnie the Maid, 1981.

Horse in West Virginia Mountains, 1969.

Horse in West Virginia Mountains, 1969.

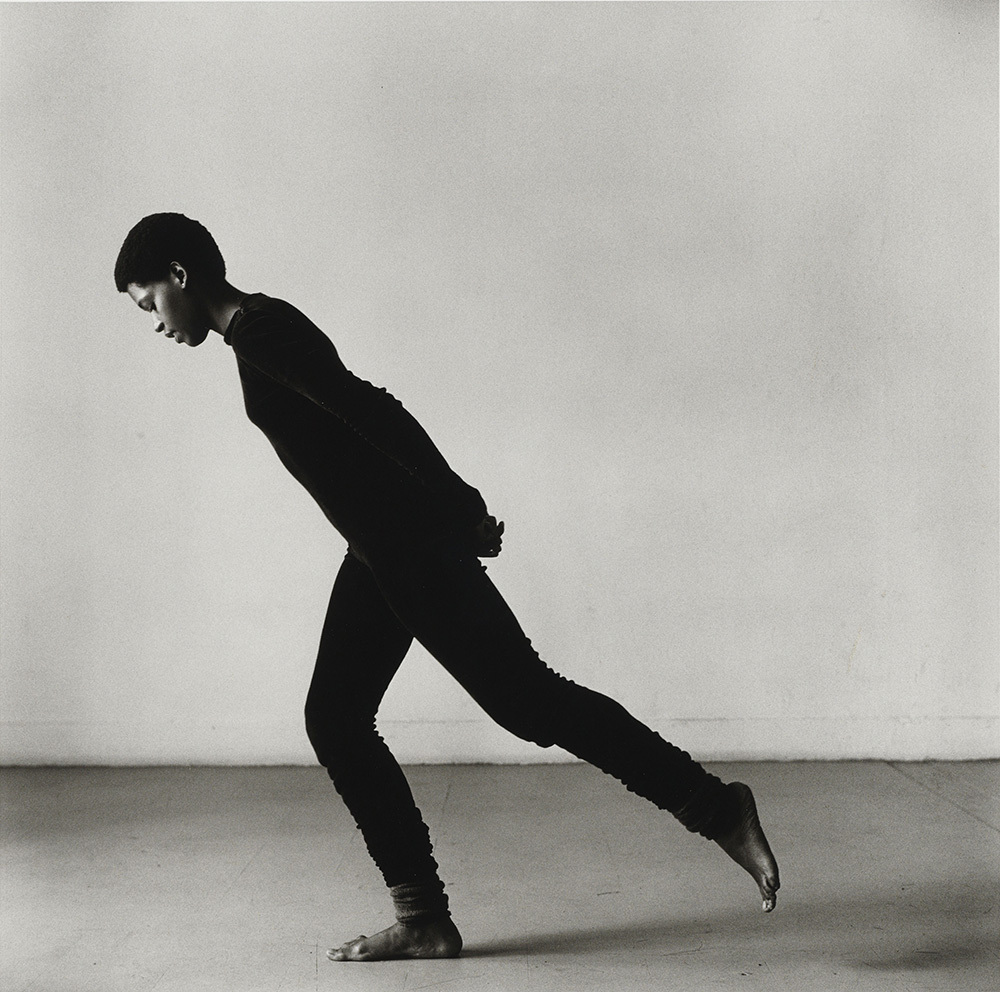

Sheryl Sutton, 1977.

Sheryl Sutton, 1977.

Self-Portrait Jumping (1), 1974.

Self-Portrait Jumping (1), 1974.

Peter Hujar: Speed of Life is on view through May 20th at the Morgan Museum and Library.