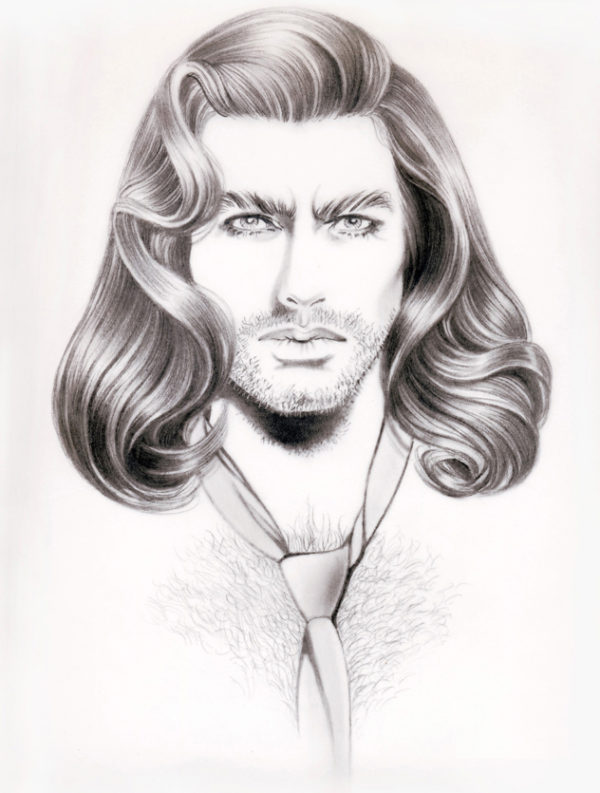

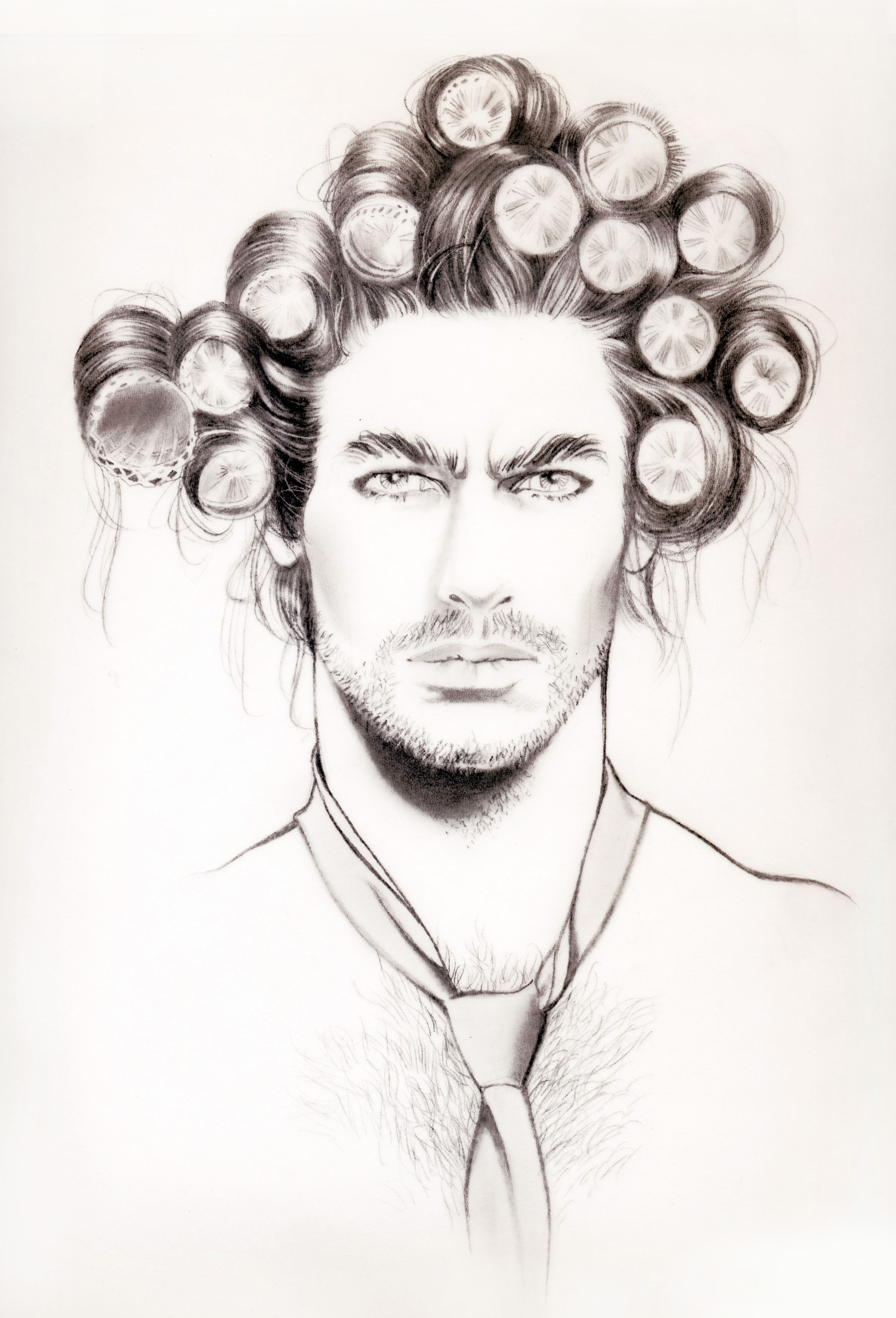

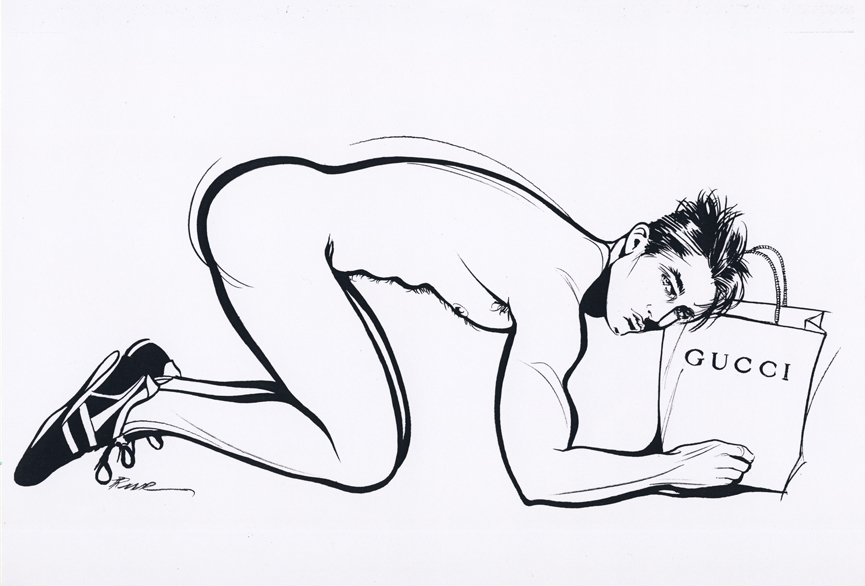

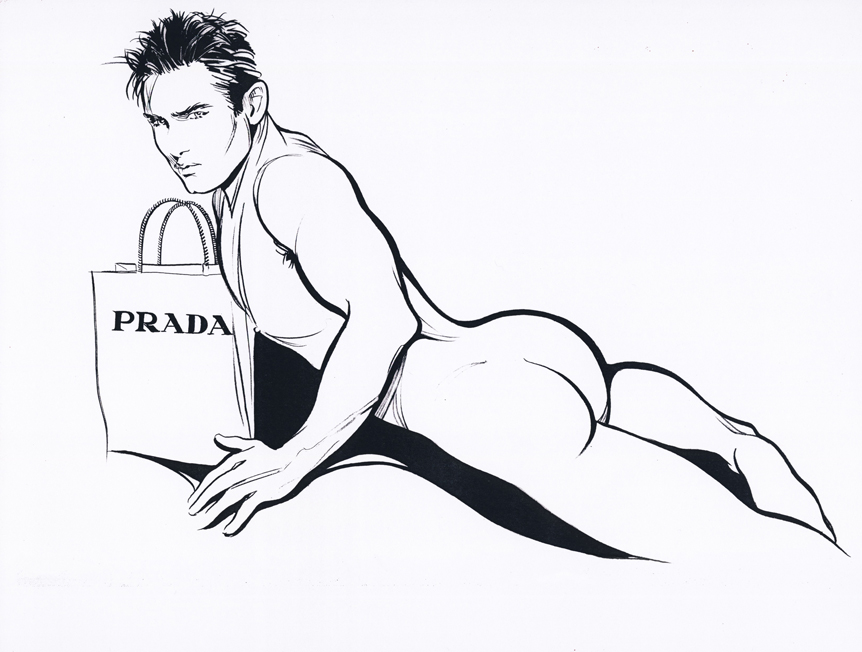

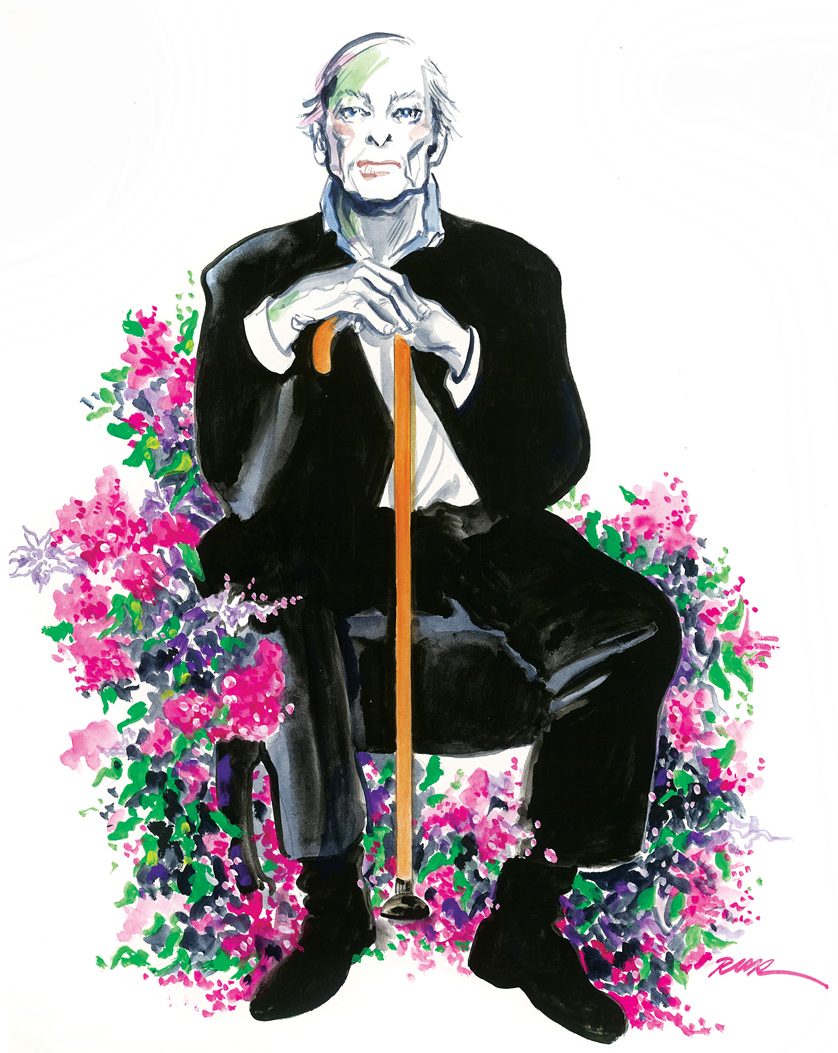

ILLUSTRATIONS BY ROBERT W. RICHARDS

Robert W. Richards’ Dreamboys

The renowned illustrator on redefining sex and fashion, the Manhattan dreamscape and the end of bitchy.

Robert W. Richards began his career as a fashion illustrator, traveling the globe and sketching runway shows, both enamored by and afraid of the clothes he drew. But it was when he returned home to New York for good that he began focusing not on couture clothing but on what lay beneath. Long, lean, sculpted male bodies became the chief characters of Robert’s drawings — all isolated images devoid of background and unnecessary detail. “A good drawing should speak for itself,” Robert told us. His drawings do.

Plenty of nods to fashion or labels are illustrated with whimsy and lightheartedness, yet the boys Robert depicts are often strong and severe. His most recent work — a series of nude boys with designer shopping bags — encapsulates his perfect intersection of fashion and sexuality. Here they are: simple line drawings, sexy yet soft. We spoke to Robert about his arrival to New York, his imagined-turned-real lover, and how he escaped the fashion world to illustrate a world of his own.

How did you land in New York City? I left home, in Maine, when I was very young. Just a little bit shy of 16 in the late ’50s. I went to school in Boston, but always I was conscious I wanted to live in New York. Boston was just a stop along the way for me.

Was it difficult leaving your family and small-town life? My mother didn’t want us to dream, because she had had a lot of disappointments in her life. She wanted us to be content with our lives as they were. But I wasn’t content with my life. Not that it was bad — it certainly wasn’t good — but no, that life was not for me.

Tell us about your first year in New York. I had a best friend in art school in Boston who had moved to New York ahead of me. He kept saying to me, “You’re wasting your time there, come to New York,” so I moved into a very nice apartment with him and his boyfriend, who I didn’t like.

The apartment we lived in, 333 East 69th St., became a very famous apartment. After we moved out, it became the designer Geoffrey Beene’s, and it became one of the most photographed apartments ever. Of course, he furnished it much more lavishly than we did.

The living situation became an unhappy one because my friend was totally convinced he was in an idyllic relationship, and he kept nagging me constantly that I had to find a boyfriend, that I had to settle down. Meanwhile, I knew that this worshipped boyfriend of his was keeping a boy downtown, and it became more and more difficult for me to be lectured constantly about how happy he was when I knew he was living in a fool’s paradise. So at that point, I decided to go out on my own.

What kind of work were you producing at that time? Especially in that environment . . . . I was doing fine! I mean, considering I came to New York and they were the only people I knew. I was always a self-starter. For a while, I commuted three days a week to Philadelphia, where I worked for [the department store] Wanamaker’s. That was the first illustration job I had where I was able to accumulate a portfolio that meant something. And then I came here and did all the usual routines — layouts for Gimbels and Macy’s and shit like that. But I never resented it. I was just happy to be here and to be working and meeting people.

Who was someone important or exciting that you met during those formative years? One day, I was going down the street — Madison Avenue, in fact — and this very kind of crazed-looking woman stopped me and said,“Who are you?” I said, “Oh, I’m Robert.” And she said, “Well! What are you doing? I’ve got a thousand people for you to meet.”

Her name was Tiger Morse, and she owned a boutique within a famous club called Cheetah. She started introducing me to wealthy men, and she taught me some of the tricks of the trade — which I never used! Well, once I did. I thought it was a little whorish.

Her name was Tiger and she worked at a club called Cheetah? Well, yes, a boutique within the club. She was a very well-known figure at that time, one of those “it” girls in New York. You know, short hair, platinum blonde, extravagant makeup. She was great. And very, very nice to me always. She said, “I’m going to give these wealthy men your phone number, and when they call and ask you to dinner, you say the name of any expensive restaurant you want to go to.”

So I would call and say where I wanted to go, you know, a Friday at 8. And she would say, “You go there on Friday at 8, and chances are 90 to one he’ll show up. And if he doesn’t show up, what have you lost? At least you didn’t get taken up to some stupid restaurant to sit with some stupid man.”

Do you think boys can still work that today? I’m not giving you advice! It was a different time — homosexuality was more guarded. When I first came here, in order to go to gay bars you had to have on a suit and shirt and tie. It was considered dangerous — not to me, because I had nothing to lose, but for guys with families or whatever. These bars were often raided — you’d be standing there having a little drink and the cops would bust in, make you lie on the floor, and write down people’s names. It was absolutely ridiculous.

Your early career focused on fashion. How did you make the transition from what you saw on the runway to what you saw in your head, especially in regards to male sexuality and the male body? I’m very interested in fashion. It’s always been a major part of my life. Working in it, I didn’t like very much. I found it . . .empty. You would sit and look at a bunch of editors, who were these dowdy little women from here, there and everywhere who would never wear the clothes they were writing about. Whereas wearing [the clothes I saw] was how I related to fashion. I wanted it! I was afraid of it.

When ready-to-wear was introduced in addition to couture — and what was once a twice-a-year thing became four — I got tired. And I didn’t like ready-to-wear shows. I still don’t like them; they are very corporate. So, one night, I got off a plane and called my editor from the airport and said: “This is my last trip. I can’t do this anymore.”

I came back here, and it suddenly occurred to me I had nothing to do. Then I thought, “I want to draw the people who wear the clothes on the runway — without the clothes.” You know, these beautiful people. I just sort of mulled this over in my head for a while, and then I thought . . . “gay.” Not that gay was a big revelation for me, but it never occurred to me there was this gay world I could draw in. Anyway, I started doing it, and it became a world I inhabited for a long time.

Was it difficult to find spaces to develop and showcase this new kind of work? I was one of the founders of the Leslie Lohman drawing group, which they have on Wednesday nights at their museum. It’s very graphic, usually one man, sometimes two. It’s very hot. They have great guys, and they’re asked — if they are willing to do so — to shoot nude on the very last pose. From a quarter to 10 to 10 o’clock, these guys are just in a sweat.

It’s fun, but I’m fickle. Which has either been a huge disadvantage or advantage. I get bored very quickly. I have very solid friendships that I have had for many years, but basically, I’m a fickle person. I’m just like, “Enough.” Not in a cruel way! But like, I’ve had it. It’s always been that way with me. I move on to another plateau.

I started curating major shows, although there’s no money in it. I never made any money. Well, I did make very good money, but I spent it. And you know what? If I did make big money tomorrow, I’d spend it.

How do fashion and sexuality intersect in your drawings? I’m conceptual as an artist. I don’t paint. I don’t do drawings with flesh tones or shadows. Boys in the forest, with the whole forest depicted, rocks and the sea — I don’t do that.

It’s a choice. It’s not that I can’t. A good drawing should speak for itself. If you draw a woman in an evening gown, you don’t need to put a chandelier behind her to know what it is.

I think that no matter what people put on or what is being described as fashion at that particular moment, it’s always about sex. Why do we get dressed up to go out at night? It’s all about allure and setting up an image for yourself.

Do you think gender expression plays a role in setting up that image? I’ve always liked things that straddle the genders. I’m not interested in drag for myself, but I love subversive drag, like Joey [Arias]. And of course Amanda Lepore, who I think is one of the great creations. I mean, she’s a great work of art. Taking yourself and making yourself into something like that is so admirable.

No one ever says someone like Ellen DeGeneres is in drag, but she’s in total drag every day. She’s always dressed as a boy. Not a man, but a boy. But RuPaul is considered a whole other thing. One is as dramatic as the other in certain ways, just perceived differently sociologically.

There are only two things that women haven’t taken from men that men can assert themselves with: One is facial hair, and I think it’s very political and very sociological. The other thing is jockstraps. You can’t fill it, girl. And that’s it.

Tell us about the pretty boys with the shopping bags. It’s just a whim. Intimidating gays with money. I got this idea to do these boys with bags indicating their tastes or the fact that they are willing to accept gifts.

Are the boys you illustrate based off people you’ve met? The brunette boy. He appears twice in this series. That’s the boy I’ve always drawn. And it’s a very strange and eerie part of my life. Because I met him.

Before or after you’d been drawing him? Way after. I’d been drawing this dreamboy for many years. And he became the great love of my life.

I’m French, you know. English is not my first language. One day, I ran across this sentence in a book by the French author Colette about a boy named Chéri. He was a bad boy who preyed on older women, made them fall madly in love with him, and took from them. Colette described Chéri as being “very beautiful, with alabaster skin, jet black hair, and a face that turned navy blue from the cheeks down every afternoon at 5.” I can’t explain what that did to me — it was the hottest. I jerked off over that sentence for years, just to the idea of this boy.

So you first discovered this boy in a Colette novel, reimagined and drew him for years, and then finally met him, in person, in reality? Yes.

That is absolutely wild. What’s the story of how you met? For about 26 years, I had Thanksgiving with a group of friends who are now all very prominent. One year, around 11 o’clock at night, the doorbell rang, and he entered the room. I couldn’t believe it. I didn’t want him to come anywhere near me. I was so overwhelmed, and this wave of almost nausea came over me like a lurch.

But he did come near me and said, “I know who you are. I’d love to talk to you someday,” and I said, “That’s certainly possible,” and he said OK, and he left. Over a year later, the telephone rang, and he invited me to a jazz show at the Blue Note. After the show, we came back into the lobby [of my apartment building] and it was very awkward, because there was so much tension. He walked a few steps away and then said, “I forgot my briefcase!” So we got into the elevator, and he was just looking down and all of a sudden he said, “There’s no briefcase.” And we stayed together, for four and a half years, from that day until he died.

What do you feel every time you draw this person? It’s just second nature to me. Every artist has his person. I’ve gone on to other things, but not really. I’m not obsessive, and I can do other faces, but often they end up resembling him. Not by intent, but by the way my hand is programmed.

What are you conscious of when you illustrate the male body? Which features do you like to highlight or accentuate in your drawings? Grace. Gracefulness. Rhythmic lines. I like long, lean bodies as opposed to tight. I draw them if I have to, but it’s not what I like. Basically, I think I like pretty men. No, I know I like pretty men. Both to draw and to look at, and to see. I’ve had a very long experience of drawing very pretty men.

How do you think your illustrated man — pretty, hairless and lean — would be valued in the hierarchy of today’s gay male attractiveness, where the muscly, tattooed and bearded man seems to be having his moment? That man is cliché. That obviously sexy man walks into a bar and there are instantly 20 people who want him because he has facial hair, tattoos, big pecs and a big bulge and all that stuff. It’s really boring. It’s like, when he enters the city limits he gets a kit for how to be an attractive gay man. That’s not for me. Not even for a trick. I like dancers’ bodies: long limbs, long muscles, as opposed to that scrunched-up look with short little muscly arms. It’s not my aesthetic.

What’s next for you after the bag series? I’m doing a book. That’s my main endeavor at the moment. Not necessarily a gay book, though it’s very gay. It’s 50 anecdotes with either famous or notorious people that I’ve had encounters with. And each anecdote has a drawing. Some are vintage, but most are rather new. The stories are funny — it’s not a bitchy book. Some parts are bitchy, but it’s the person who is bitchy, not me. Bitchy is over. Bitchy is fucking boring. It’s a nice book.

I wasn’t interested in doing a bio of any kind — who cares? I’m not famous or anything. I’m just here!

How do you look back on your successes in New York and how you’ve gotten to where you are now? I’m dead broke, but I don’t care about the money. The most interesting things I’ve ever done in my life have been for no money. The things I’ve done for money have been some of the most humiliating. Not that I haven’t done good things for money, but the big things have been for no money. So that’s that story. This is what I wanted to do. This is what gets me out of bed. This is what keeps me hoping.

When I do croak, throw some pencils into the casket. I’ll still be doing something.

This story was previously printed in GAYLETTER issue 1.

Gore Vidal illustrated by Robert W. Richards for GAYLETTER Issue 3.

Gore Vidal illustrated by Robert W. Richards for GAYLETTER Issue 3.