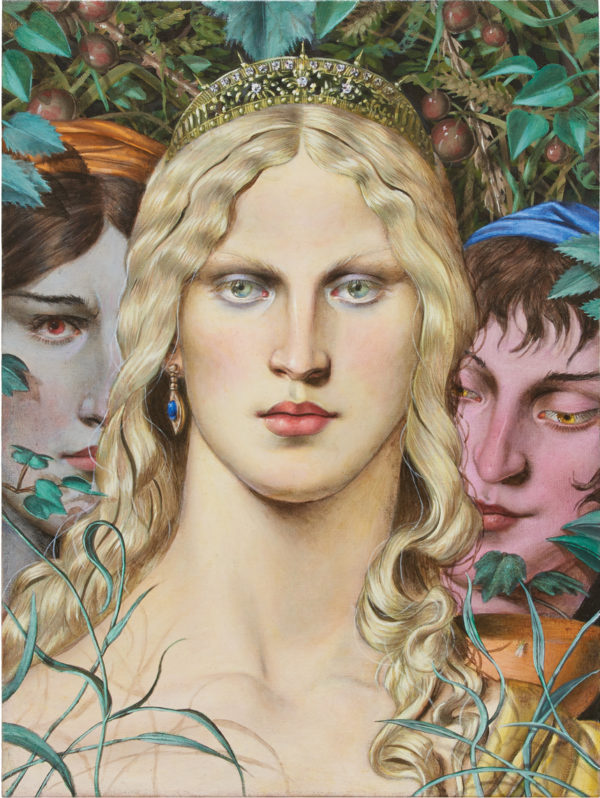

“Titania” (2019). All images of artwork courtesy of the artist and Soft Opening, London. Photography by Theo Christelis.

RYAN DRISCOLL

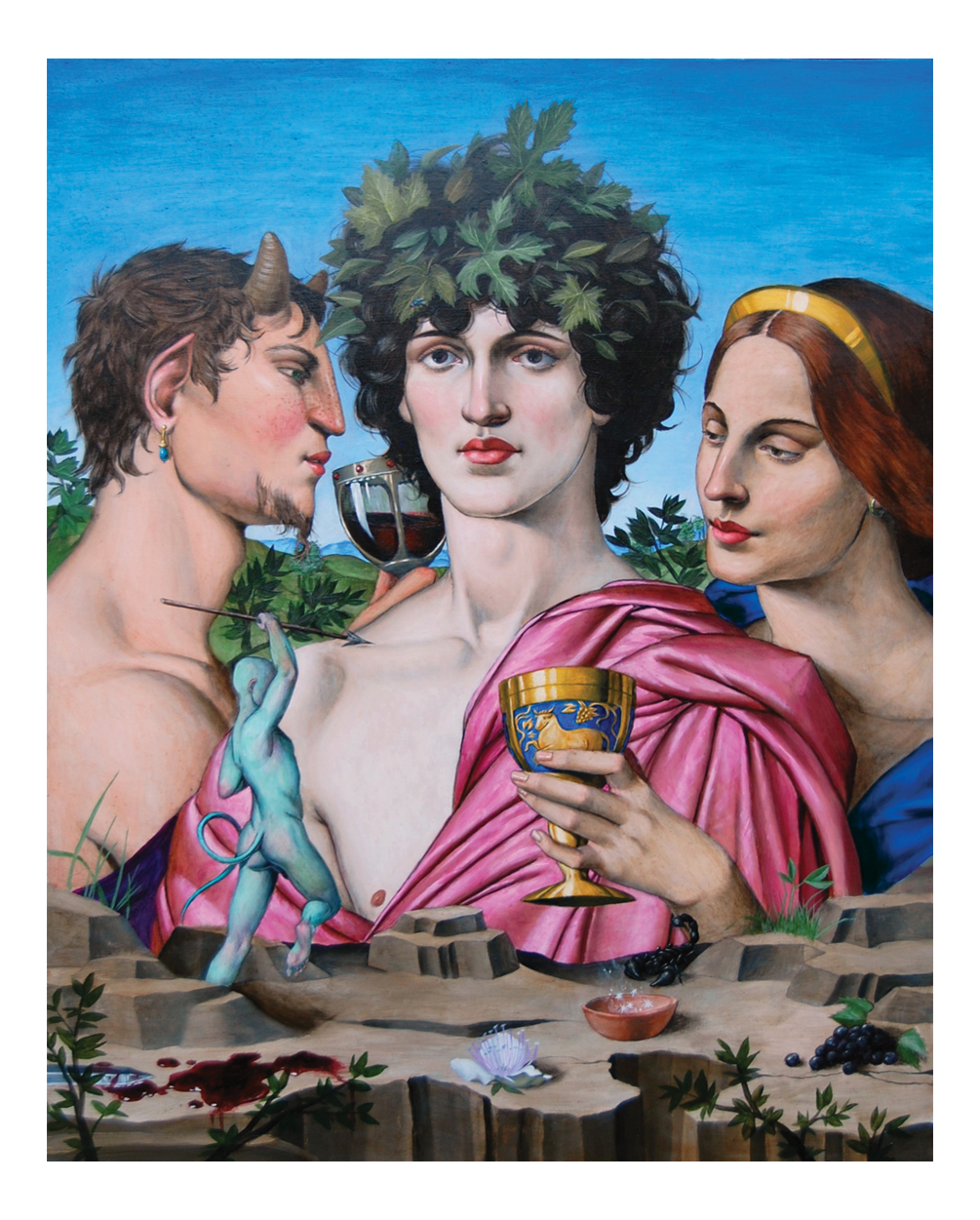

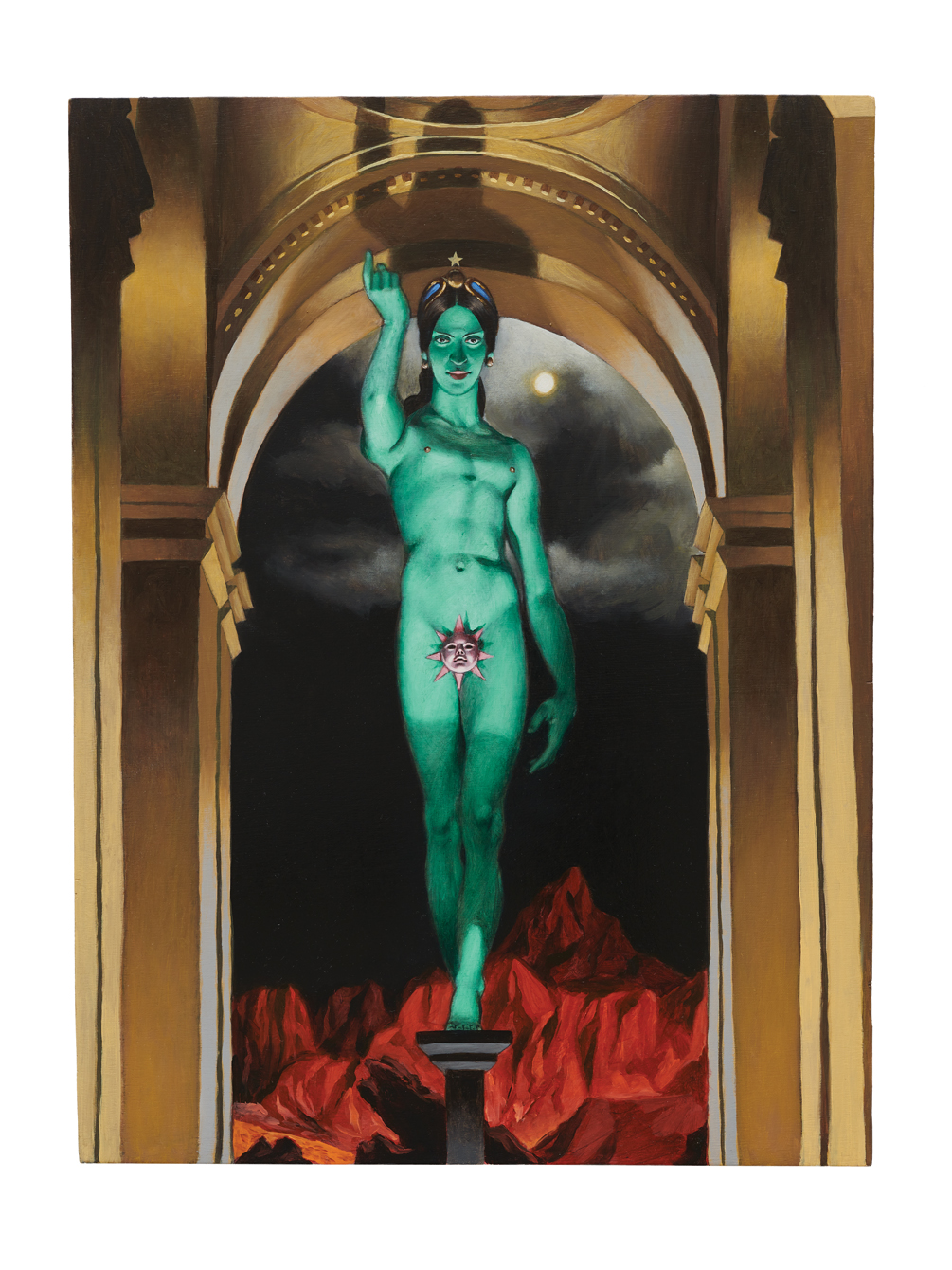

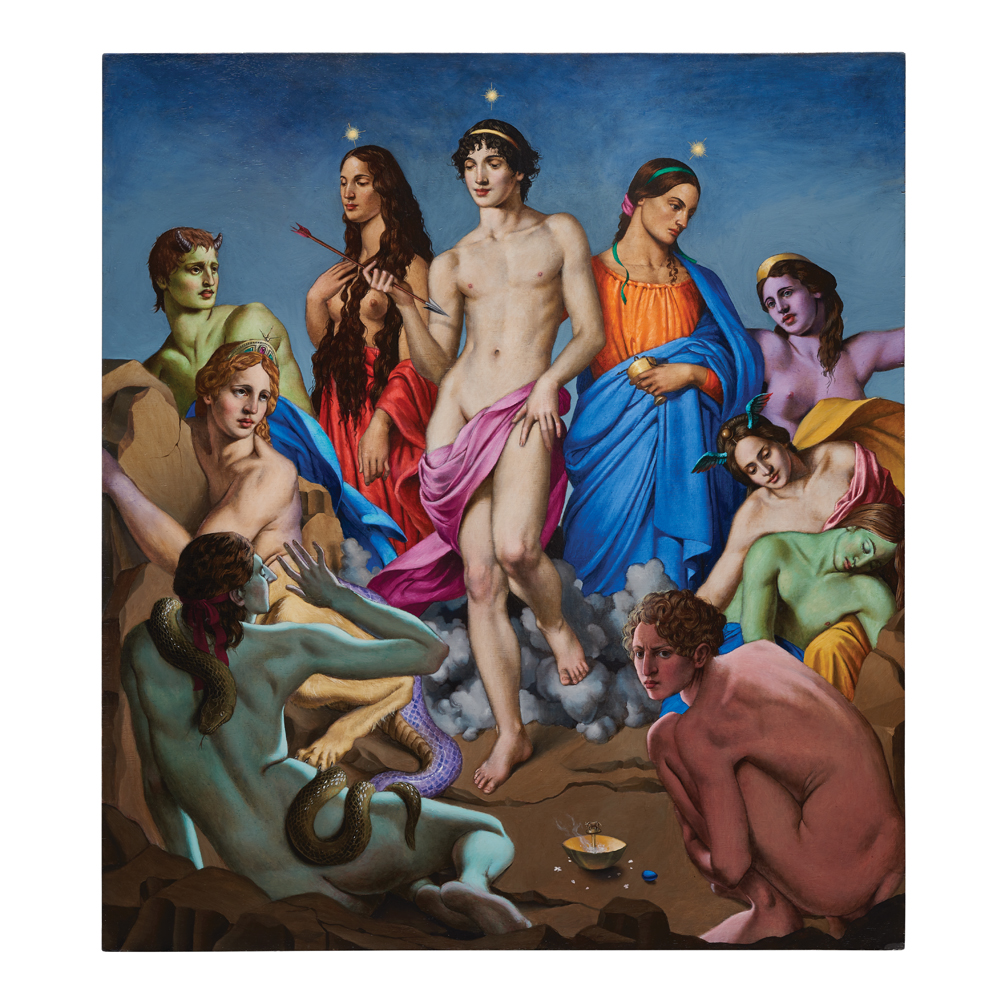

In the heart of England is Corby, an old steel town, which painter Ryan Driscoll calls “the epitome of the color gray.” Since childhood, Driscoll was forced into the dutiful British pleasure of reading Shakespeare, and despite his dyslexia, fell in love with the stories. Occasional trips to the National Gallery in London inspired his tendency toward the mythological melodrama and old-school flare of the museum’s massive allegorical oil paintings, and when at home, he grew up watching old Hollywood films. “I’ve probably seen Cleopatra about ten times through,” he admits. Modeling for his own paintings, Driscoll has become something of a performer, assuming a range of characters — monsters, witches, warriors, queens, fairies, deities. It’s fantasy through a queer lens, somehow sweet but also dry, outrageous and campy at the same time as it’s gentle and unrelentingly romantic. Cindy Sherman meets William Blake, Michael Powell meets Max Ernst, Bronzino meets Joseph Campbell — Driscoll offers his own spin on traditional iterations of the hero and villain, becoming a shape-shifter for an assembly of elegantly surreal dramatizations.

Mostly working in oil and watercolor, Driscoll is largely self-taught, his pseudo-Mannerist style highly informed by observation. “No one else uses the technique I use, and they probably shouldn’t,” he laughs. “I’ve got a feeling it’s not economically or logistically sound.” Only a few of his friends are artists, and he feels mostly on the outside of the current vogue of figurative painting in the art world. He spends most of his time painting and sees social media as a way to get eyes on his work. Often the mythological context and social symbols are lost on the viewer, though he is not dogmatic, enjoying divergent interpretations of his portraits: “When people don’t get it, they can still engage.” In subtle ways, Driscoll revives the dreamy vision of the Pre-Raphaelites by showing the scenes of his imagination, stepping into someone else’s shoes, as we all might do with our protagonists, to distract ourselves, to escape.

“Dionysus and his Followers” (2019).

“Dionysus and his Followers” (2019).

“Uranus” (2020).

“Uranus” (2020).

“Saints and Sinners” (2019).

“Saints and Sinners” (2019).

“St. Michael and the Devil” (2018).

“St. Michael and the Devil” (2018).

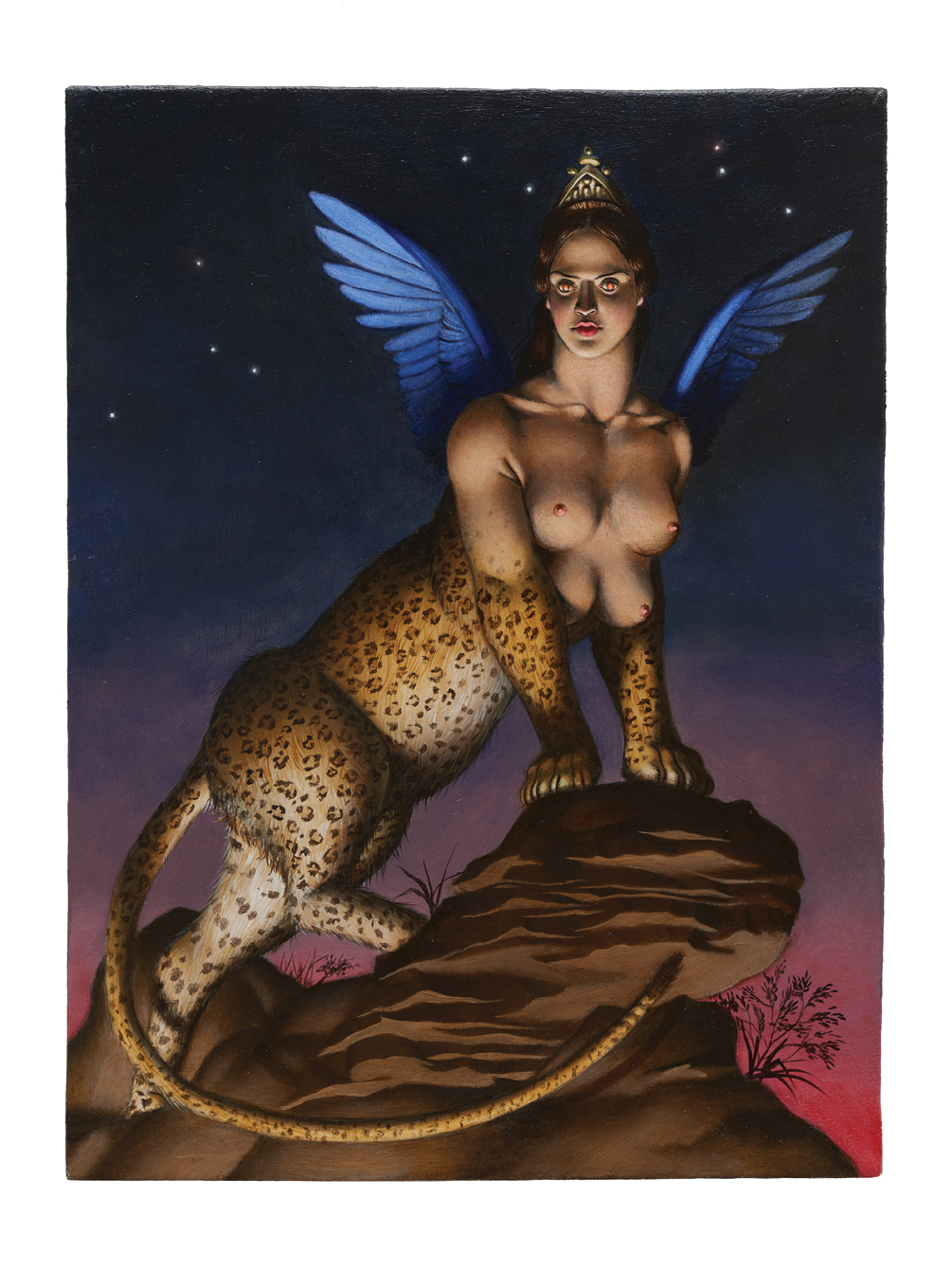

“Sphinx” (2021).

“Sphinx” (2021).

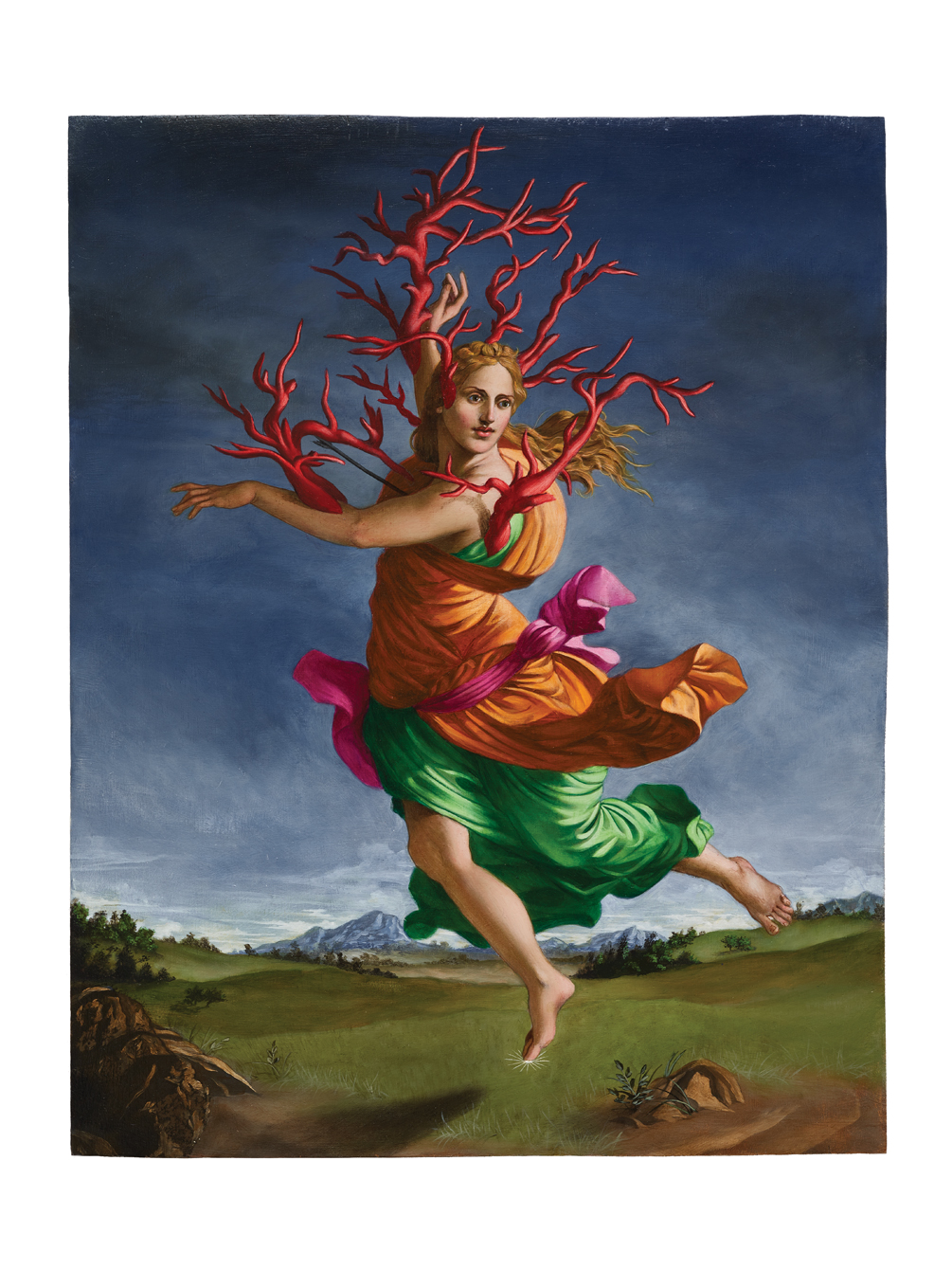

“Daphne” (2021).

“Daphne” (2021).

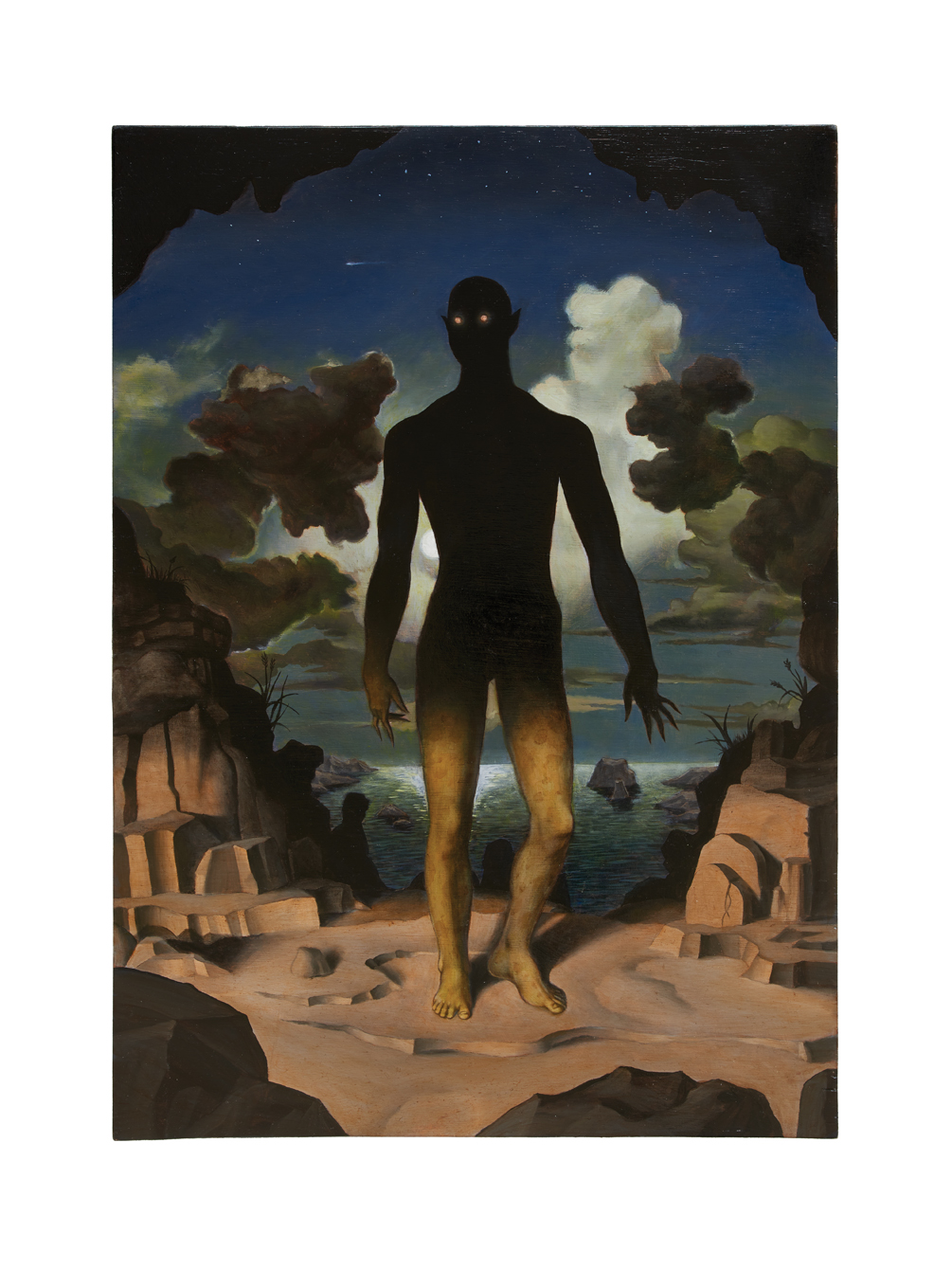

“Caliban” (2020).

“Caliban” (2020).

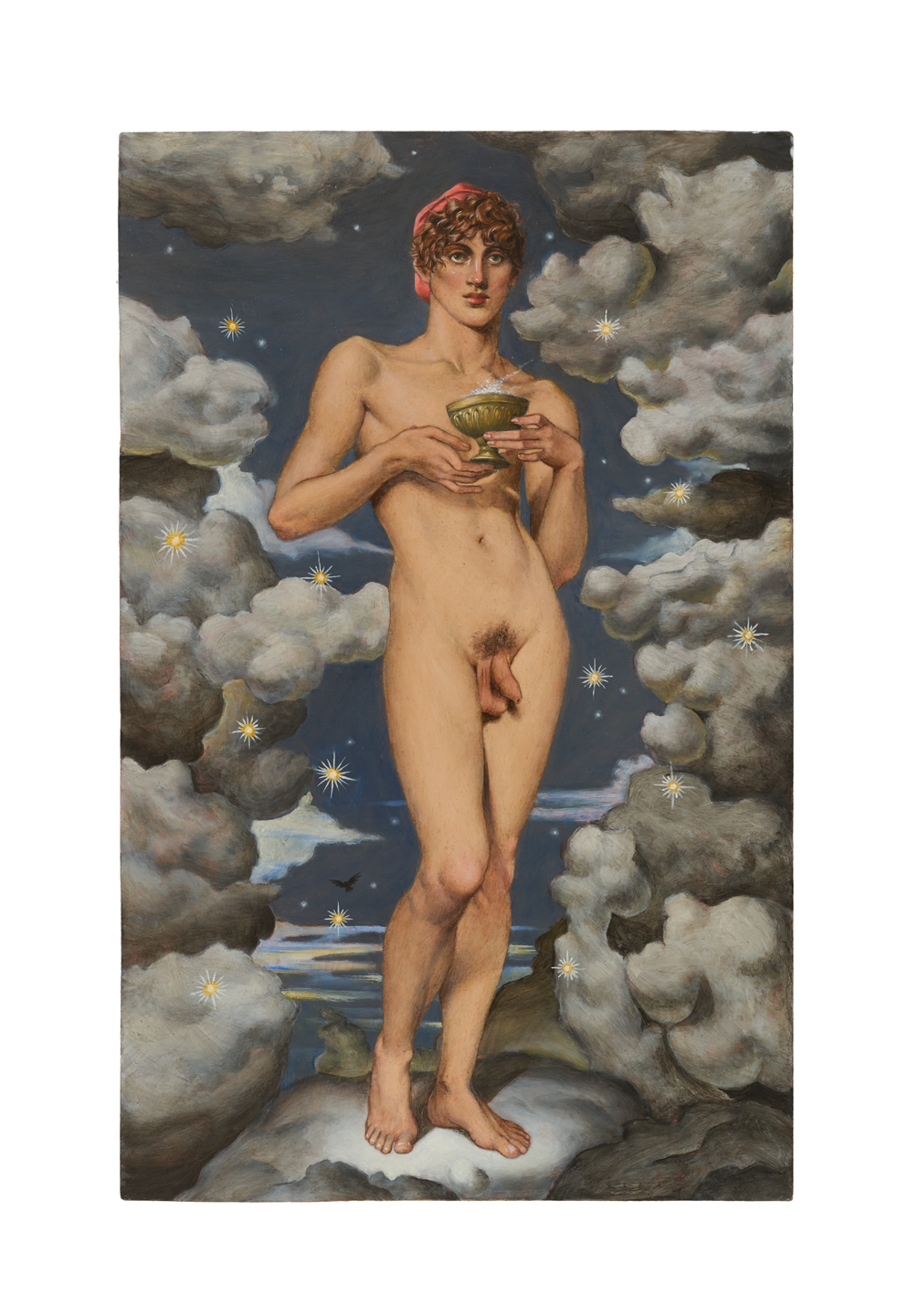

“Ganymede” (2019).

“Ganymede” (2019).

Ryan Driscoll self-portrait. Corby, United Kingdom. June 2022.

Ryan Driscoll self-portrait. Corby, United Kingdom. June 2022.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here.