ILLUSTRATIONS BY BRAULIO GONZALEZ

Stories Unsilenced

Any practice that aims to control who has access to information, such as banning or removing books from libraries and schools, has always been about delineating whose voices and ideas matter in this society. The objections to who and what readers have access to amounts to a fight over who we empathize and align ourselves with in this world. In this moment of rampantly rising attempts to challenge and ban books across the U.S., books that explicitly take on issues of sexuality, race, gender, or that explore multiple intersections of these identities, are typically the first to face backlash. These are often books that reflect back the feelings and experiences of the underrepresented. The vocal minority advocating for the removal of certain books from public life complain about unfiltered depictions of sex and sexuality (often labeled as “pornographic”), violence, matters of race or racism, even citing “death” as a topic that warrants censoring.

Books have a power that no other media has successfully replicated — they fully immerse you, the reader, alongside the consciousness of someone else. To engage with a story in print is to take it into your mind, to feel and think with the text, and it’s that realm of thoughts and experiences that can be the best bridge to understand someone else’s life, it’s the closest we may ever get to seeing the world through another’s eyes. And it’s exactly this ability to inhabit alternative selves, to empathize and connect, that makes these books targets for removal. Notably, young adult and children’s literature are focal points of the current increase in book bans, books that can (and do) serve as powerful tools to gain knowledge about the contemporary world, fortify readers’ own sense of self, and even momentarily, to embody the experience of another.

Spotlighting the need for authentic, unfettered self-expression, branches of Aesop’s Queer Library will open across New York, Los Angeles, and Toronto throughout Pride 2023. Readers and visitors are invited to select a complimentary book from the selection to bring home.

The full list reflects the creative and literary potency of the writers and artists who many seek to silence. Across novels, graphic memoirs, and essays, these authors’ works provide us a truer look at this thing called life, and the subtleties, complexities, and joys at its center.

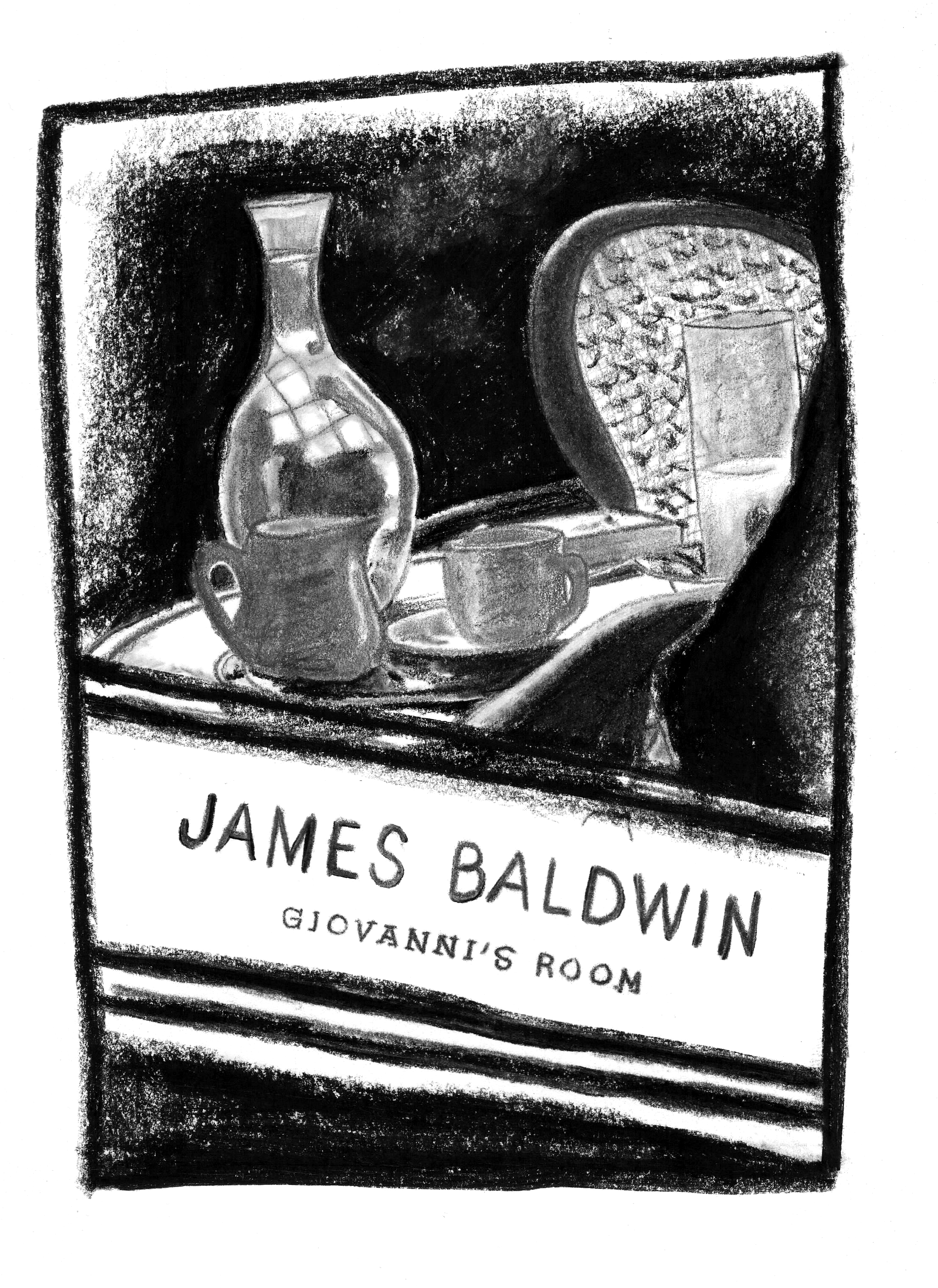

Giovanni’s Room — James Baldwin (1956)

Giovanni’s Room — James Baldwin (1956)

James Baldwin moved to Paris in the fall of 1948, seeking reprieve from the forces of discrimination dominant in the United States. While there, he wrote Giovanni’s Room, his second novel, about an American abroad who falls in love, drawing from his own observations and experiences. The protagonist, David, believes he’s in love with the young and alluring Giovanni. But his feelings for Giovanni are turbulent and complicated. David says, “I do not know what I felt for Giovanni. I felt nothing for Giovanni. I felt terror and pity and a rising lust.” Been there, babe. The effort of uncovering and untangling one’s own feelings of desire, and the perceived ease with which we can or cannot declare those desires are part of the intense tensions at the center of Giovanni’s Room. Banned for undeniably homosexual themes and characters, Giovanni’s Room captures an aching and earnest curiosity about moving through the world as Other, its characters asking themselves and their flames, “can I love, and what does love look like?”

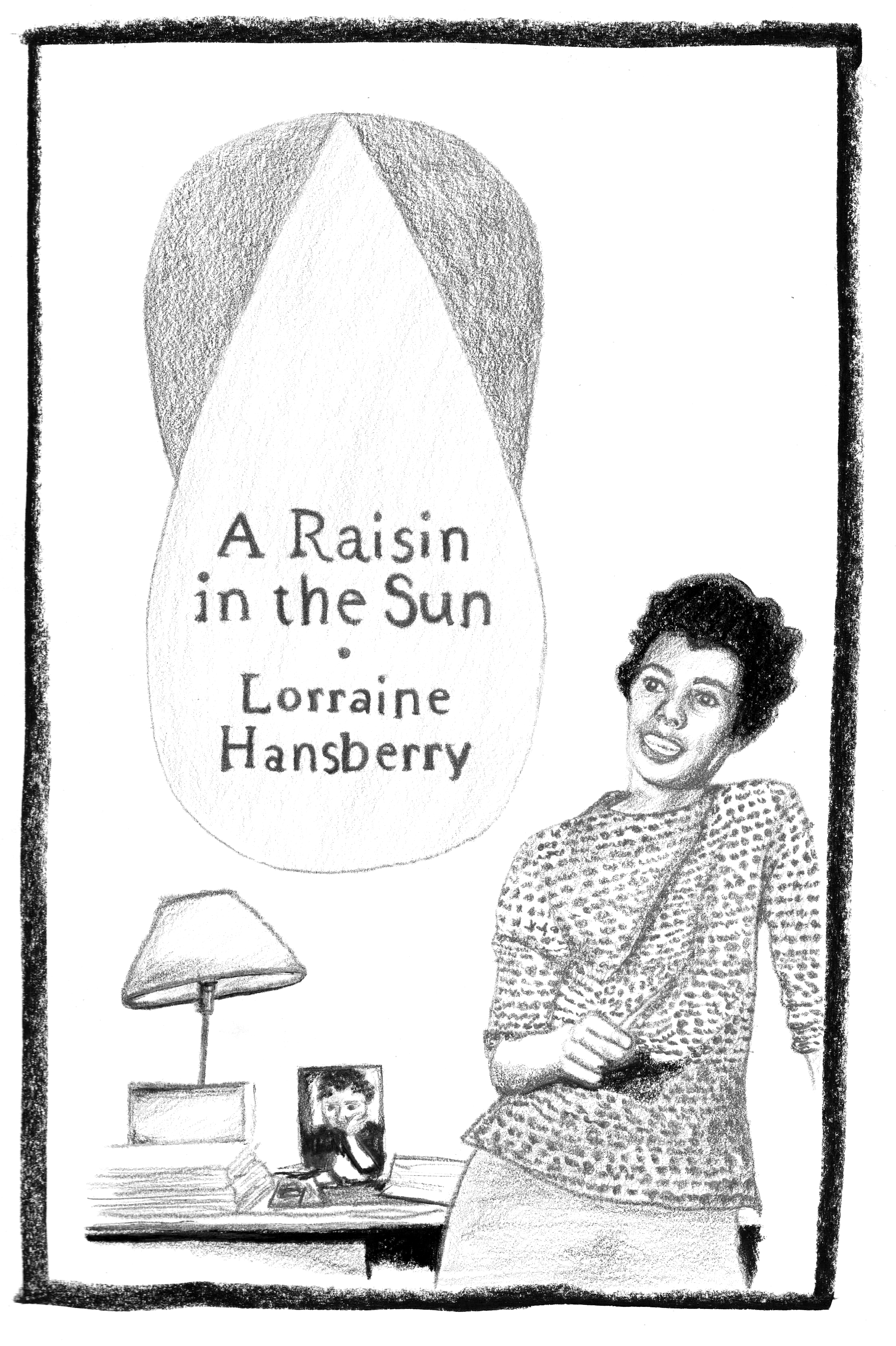

A Raisin in the Sun — Lorraine Hansberry (1959)

A Raisin in the Sun is one of the great American plays. Set on Chicago’s South Side, it follows the Younger family as they determine how best to spend the payout from an incoming life insurance check. It takes its title from a line in “Harlem,” a poem by Langston Hughes. When it premiered in 1959, Hansberry became the first Black woman to write a play produced on Broadway. Though Hansberry and her acclaimed play are lauded today, both faced intense criticism and even calls for censorship from the gatekeeping, theater-going public during its run. Raisin was also initially criticized by more militant Black playwrights who thought it wasn’t political enough for the times. It was only decades after her death that Hansberry was “officially” identified as a lesbian, but throughout her short life (she died at the age of 34) she wrote in support for feminist and lesbian activist organizations, only signing with her initials or using a pen name, arguing for same-sex rights. In her posthumously published diaries, she wrote she was committed to “this homosexuality thing,” then comments, “I will create my life — not just accept it.” Honestly, same.

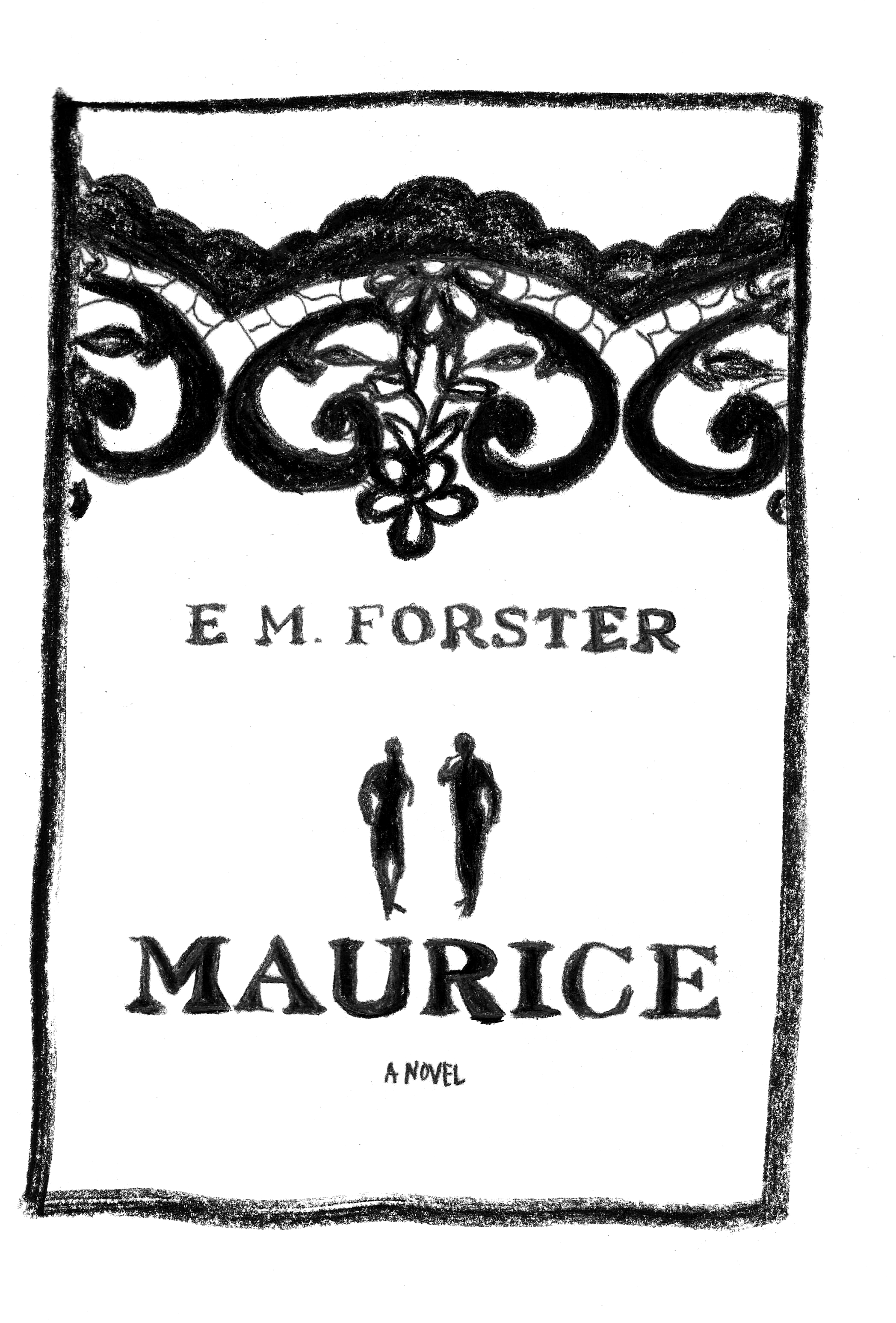

Maurice — E.M. Forster (1971)

Maurice — E.M. Forster (1971)

Is there anything gayer than a novel called Maurice? I love it! E.M. Forster wasn’t publicly recognized as a homosexual until after his death, but anyone reading his work, especially Maurice, might have come to that conclusion without having read the official notice. Published the year after Forster’s death in 1971, the novel is a coming-of-age story of the titular Maurice, his adolescent escapades, and the murky affairs of young adulthood, run-ins with distant and ambivalent men, but ultimately Maurice’s story ends on a happy note. Our Maurice is a yearner, longing for dark privacy, massive free space, and an existence in a natural, utopian world unavailable to him, and finding respite or private, safe spaces to be fully oneself is one of the novel’s core explorations. Forster himself wondered if publishing Maurice was “worth it,” as attitudes towards homosexuality in mid-20th-century England would have put him at risk of legal prosecution. But Maurice is canon, a mainstay in the history of gay literature, transgressive in its depiction of a character who did not conform to the socially accepted way of life who still finds a measure of happiness in the end.

Sister Outsider — Audre Lorde (1984)

“And we must constantly encourage ourselves and each other to attempt the heretical actions that our dreams imply, and so many of our old ideas disparage,” writes Audre Lorde in her 1977 essay “Poetry is Not a Luxury.” These “heretical actions” include her own poetry and activism throughout the 20th century as a Black lesbian, and her fervent advocacy for the use of our voices as a vehicle for change, not only the act of speaking out, but the cultivation of a voice that is really one’s own, not a product or inheritance from a Eurocentric, oppressor mentality. Sister Outsider collects Lorde’s essays and speeches in which she forcefully and lyrically expands on the generic definitions and limitations of feminism as defined in her lifetime. Lorde wrote the bulk of the essays in this collection in a two-year span following her cancer diagnosis. Understandably so, life, death, and the legacies we pass down to future generations, are some of the book’s resonant thematic foundations. Perhaps the most quoted of Lorde’s declarations, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” holds an ethos that permeates Sister Outsider as well: mistrust what you are taught, this is the way to rebuild a “world of possibility.”

Fun Home — Alison Bechdel (2006)

Fun Home — Alison Bechdel (2006)

Often challenged for its representations of homosexuality and potentially disturbing subject matter like suicide and emotional abuse, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic is one of the most iconic works of graphic literature of this century, queer or otherwise. The book is an illustrated chronicle of author Alison Bechdel’s early life, coming of age in the family funeral home (also known as the “fun home”). The non-linear, cyclical structure of the graphic memoir revolves around Alison’s relationship with her distant father, Bruce, and her attempts to connect with him. What the adult Alison narrating this story knows that her younger self doesn’t, is that Bruce is also gay and closeted, making his monitoring and enforcing of Alison’s gender performance all the more complex. Bechdel’s use of sequential art to tell this story allows for multiple points of view, and an increased emphasis on looking at what lies hidden just under the artificial surfaces around us, returning again and again to moments where she tries to make sense of Bruce’s behaviors, which we the reader are allowed to consider from various vantage points. When Bruce does come out, the fun house mirror effect is in full force, as Alison sees him, and herself, in flipped roles, and feels “parental” hearing his confession. The genius of Fun Home lies in these reflections. How does one queer life influence another? And how do we find the willingness to be fully seen?

Flamer — Mike Curato (2020)

Mike Curato’s graphic novel, Flamer, tied for the most banned book in the fall of 2022 according to PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans. Unflinching in its portrayal of adolescent, anti-gay bullying, alienation, and the self-hatred born of an intolerant environment, Flamer follows Aiden, a 14-year-old boy spending his summer at Boy Scout camp. He’s self-conscious about his weight, about being biracial (Filipino and white), and confused by the tension and pain that roil his relationships with other boys and men, and he tries to process conflicting feelings of guilt and shame, alongside a flicker of hope for something better while navigating a budding crush on his tentmate. Aiden’s trial by fire comes from his tormentors at camp, but also from within himself, and Curato’s searing red and orange flames on an otherwise grayscale spread symbolize the engulfing intensity of feeling that comes with anxiety and thoughts of self-harm. Flames, literal and figurative, are abundant in the novel, and Curato’s deliberate play on words with the title and imagery allude to something bigger at the heart of this story: that heat and light can show us the way to self-acceptance. Curator’s novel will be a defining text for young queer readers for generations to come.

All Boys Aren’t Blue — George M. Johnson (2020)

George M. Johnson’s memoir-manifesto, All Boys Aren’t Blue, is one of the most banned books in the country. The title alone provokes. If all boys aren’t blue, then what are they? The book traces the author’s journey towards understanding themself as a Black queer person, how both of those intersecting identities take shape, and they examine how an assumed or compulsory masculinity harms us all. Johnson says that they expected there to be backlash to the book, but that the attacks against the book, challenged for “sexually-explicit” scenes, are disingenuous. However, the book ultimately has more supporters than critics. Despite bans across multiple states, readers have found Johnson’s memoir. Readers, teachers, parents, and librarians, show out for the book at school board meetings, for example. In real time, the people who’ve been impacted by this memoir, are working to keep it available to the readers who may need it most.

This story will be in print in #GAYLETTER issue 18, make sure you subscribe to the magazine for the full year to receive the next issue…