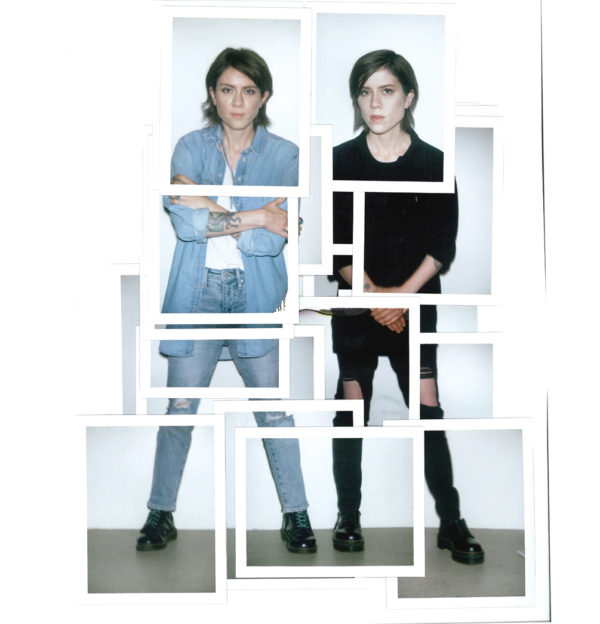

PHOTOGRAPHY BY KATT FOX

Tegan and Sara

Tegan and Sara scaled the music industry mountain and planted their names in the sky. Born Tegan Rain Quin and Sara Keirsten Quin in Calgary, Canada, the identical twin sisters achieved indie stardom with their eponymous band in the ’00s, before becoming pop icons in the ’10s, in no small part thanks to touring with Katy Perry in 2014.

Now they’re rounding the bend into the 2020s with a nostalgic turn. Their ninth album, Hey, I’m Just Like You, inspired by ’90s cassette tapes, and the accompanying co-authored memoir, High School, gave the twins a chance to look back at their teen years.

GAYLETTER spoke to Tegan and Sara each separately — Tegan about the new music and Sara about their first book.

TEGAN

One of the tracks on your new album, “I’ll Be Back Someday,” it really captures that teenage need to get away, to find a more tolerant place. Did you feel like that growing up? I mean, even as an adult I need to get away sometimes. [Laughs] With that song, though, it sounds poppy and upbeat, but the undertone is this idea that you’re anxious about facing the person that you are, anxious about admitting what you feel for somebody. While I didn’t physically run away as a young person, I definitely repressed who I was for a long time. You know, when I eventually ended up hooking up with my best friend who was a woman. It was hard for me to even articulate how I felt to her. Even falling in love with her, I still felt like I didn’t see a future where we could be together yet.

The opening track on the album repeats the line “If I hold my breath until I die, I’ll be alright.” What inspired these lyrics? I wanted to just disappear at times. That particular song is about an era where I felt this mad, crazy crush on this girl that I was close with, and we would have these sleepovers. She would ramble on and on in the dark, and I would lay next to her, listening, but also thinking how much I wanted to confess how I felt. Yet I felt so incapable. I would just hold my breath next to her, hoping not to accidentally bump up against her, or somehow give away how I felt. I was so afraid.

How did you approach the album’s production? The title track, “Hey, I’m Just Like You” is so colorful but with this ache at the center of the song. The production on the record is something I’m really proud of. We wanted to showcase different eras of Tegan and Sara, and not just make a full-blown pop record. We wanted to explore guitar again, and ’90s production. Music is moving away from those organic, human moments, so we wanted to make sure this record felt real. To have a real drummer — Carla Azar of Autolux — for the first time in a while is great.

You mentioned part of the process of making this album was reinterpreting old ’90s cassettes you found. Did you follow any rules reimagining them? We did have rules. We wanted to rewrite only what had to be re-written. If we could find a part or lyric to fill in a blank, even from another song from that era, we’d try and do that. We really wanted to not import too much of ourselves now. But we were also hesitant to make a nostalgic, throwback record, so we still wanted modern instrumentation. We definitely weren’t trying to make a ’90s Urban Outfitters piece here. [Laughs] If Tegan and Sara from the ’90s got in a time machine and visited us now, we wanted to make sure that we were making a record they’d like.

That sounds like the premise of a teen movie! Are there any teen movies you find yourself coming back to? Oh, absolutely. My God. Of course. When we were teenagers, our entire summers were spent in the basement obsessively consuming everything from John Hughes movies to Kids. I have a special place in my heart for a lot of ’90s queer teen movies. I rewatch All Over Me all the time, because it’s just so sweet, and it was really the first queer movie I ever saw.

I hadn’t considered Kids a teen movie but it totally is. It’s so crazy that young people watched it because it’s so upsetting. We must have rented that movie — I’m not joking — 30 times. I don’t know what my parents were thinking. I mean, Rosario Dawson is the queen of all queens. Ugh! Yeah. No kidding.

Are there any issues that LGBTQ women specifically encounter that you feel should be spoken on, which some of our gay male readers might not have considered? Sure. The umbrella over LGBTQ is huge, so on some level it’s natural that people focus on their own segment. We started The Tegan and Sara Foundation to focus on raising funds for LGBTQ-identified women and girls. Girls, specifically trans women, and women of color, tend to be the most marginalized in our community. LGBTQ organizations that raise money for women and girls raise half as much as male-centered organizations. Gay men tend to only give to gay male organizations. We need our allies to stand in solidarity with us, support us, and help us raise money. LGBTQ women and girls are under-researched, under-represented, and under-funded, so finding ways to give to that community would be a great way for gay men to show up.

SARA

Who were the first queer writers you encountered? Jeanette Winterson’s books were the first fiction I read that was queer, where I also knew that the writer was gay. She was taken seriously as someone in writing, and I thought that was profound. A few years ago I read Abandon Me by Melissa Febos — it felt as if it were the 1950s and I just somehow discovered this queer story. When you’ve lived in a world where there’s so much heteronormative storytelling, it feels amazing and prophetic finding something outside of that. I feel that way about Maggie Nelson and Ocean Vuong.

In your new memoir with your sister, you recount a man asking after a show, “What do you know about love?” Returning to the love songs from that period of your life now, how do you relate to them? I don’t think our society is necessarily interested in what teenage girls think about or what they desire. At those ages, I had fully formed thoughts about things, desires about people, fantasies about what I wanted my life to look like, what I wanted my relationships to look like. My sexuality was a terrifying thing. It was not simple. It was not cute, and it was not easy. It was terrifying — a narcotic. It was something that was so complicated. We have an opportunity to show that at 17, we knew a lot about life.

At those ages, men are already allowed to be complicated. Women haven’t been given that value. That man, that point of view, was everywhere. Even in adulthood. Assuming, and sort of head scratching, like, “Why would I be interested in what you have to say? Because you’re young, you’re queer, whatever.” Because I’ve been forced to consider the world through that perspective, it feels reciprocal to ask people to see it from my perspective.

Speaking of your perspective, you and your sister began documenting yourselves at four years old. How did that begin? When Tegan and I were born, immediately it was like we were famous. We were identical twins. Anywhere we went, people looked at us, people talked to us, people tried to touch us. There was a power in knowing that we were interesting to people without having done anything, just by existing. But the dark side is that it was difficult to trust people, to know what their real intentions were. It was aggravating to feel like people were constantly observing us without consent. There was always this struggle, where we were enjoying that power, but also wanting to have the same boundaries that other people have.

The way we controlled that was by filming ourselves, recording ourselves, even before we had anything to record. We would record our voices, telling stories as little kids. We were obsessed with audio. Right away, it wasn’t necessarily about wanting to be on camera, it was about wanting to control what was on the camera. In some ways, that was how we coped, how we strategized, and how we dealt with what was happening around us. For so long, we were the object being observed. Technology allowed us to step outside that experience, to control it, to know what people saw, and then to change it if we didn’t like what people were seeing.

In the memoir, an agent tells you to sign with a small label that would invest in your development. How might you expand on that advice now? I’ve seen what worked for me and Tegan not work for many people. The most important thing that I’ve learned is — I think about this a lot, now that we’re entering our 20th year in the business — it is a long life, and it is not a sprint. I don’t envy anyone coming out of the gates who rockets to fame overnight. The work required to sustain that kind of success and that kind of balance is profoundly difficult. I think to be a successful artist, or a happy artist, or anything like that, means accepting that there will always be this kind of disease, this discomfort, this unsettled feeling that there’s still more to accomplish. And instead of finding that overwhelming or depressing, it’s about finding a way to harness that, to continue to put that back in your art and your creative self.

I can say that, as someone who looks like they’ve had success and achieved all these things, I’m just as melancholy, just as difficult, and just as unsatisfied as I was when I was 17. [Laughs] So, I feel like you just have to learn to live with that version of yourself and use it whenever you can to make art. That’s all you can do.

To see the rest of the feature order a copy of GAYLETTER Issue 11 here.