PHOTOGRAPHY BY CONNOR ATKINS

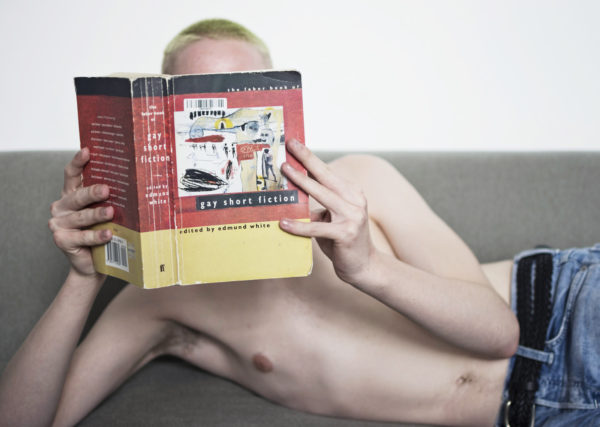

The Faber Book of Gay Short Fiction

Edited by Edmund White

Like the very best jewels from the family vault, Edmund White, in 1991, gathered together these 32 stories about and by gay men. Spurred on in his idea by a very enthusiastic Robert McCrum, renowned editor of the equally renowned Faber and Faber, White set about to unearth as many gay treasures as he could: those he remembered liking the first time he read them, those he had heard positive words about, along with a few outings from (at the time) new writers, lending the collection a contemporary as well as a historical feel.

The Faber Book of Gay Short Fiction is a valuable and valued anthology. More than twenty years after its publication, its stories crackle with vitality and talent. Here is a gala gathering under the roof of one book of every legend of gay culture and the gay literary world, men now gilt in myth, gay history and the magic of words. So many versatile writers cover these pages, it is difficult to know where to begin —

Henry James’ The Pupil, quite the most amusing of the lot, delights with its tale of a near-unresolvable bond between a teacher and his young student. Gore Vidal’s bitter vetch piece, Pages from an Abandoned Journal, appears here and the old contrarian’s voice rings out eager and strong. Here also to be found is the tenderness of Denton Welch’s alarming encounter at a Swiss ski chalet, as well as the always salty, backwater perversities of James Purdy. Readers must rejoice in Alfred Chester for his surprising paean to toilet sex, Vespasian, a piece so brave and needed, and the revered Tennessee Williams’ naughty camp horror fest, Two on a Party, and revel in the universality of Christopher Isherwood’s Mr. Lancaster, a salute to gays as a group, a global community rather than as a particular person. Here, too, for a reader’s excitement are E.M. Forster, William S. Burroughs, Adam Mars-Jones and Paul Bowles, Andrew Holleran, Alan Hollinghurst, James Baldwin and Bernard Cooper. White’s own Skinned Alive is included, hands-down the shining star in this heavenly sky of writers. The story of a middle-aged expatriate author in Paris, it climbs ivy-like upon White’s precise, lyrical prose, a fine, keen-eyed meditation on the never-before-explored emotional and romantic repercussions of POZ men in the ‘80s.

*

White’s radar in choosing these works was right on target. If there is a common theme, it is “Displacement”. The gay man knows a permanent sense of alienation from the tribe, but also the unwillingness of parents and relatives to forgive or understand, the often unwanted company of women (viewed as intrusive or unnecessary), hearty boyhood affairs, randy, never-to-be-forgotten liaisons, courtships and lovely bodies and Style, lusts, longings and sorrows — a gay Panorama egg of a subculture’s customs, costumes and secret languages, multiple forms of gay expression and male beauty. The ardor and variety of these stories is a brilliant mix, truly. Not only was The Faber a milestone in its time because it was unequalled in both scope and the level of talent represented but also because surprisingly very few anthologies of its caliber have been published since. It made history and it also has kept its cache, a high watershed place in gay literature that has not, I think, been toppled.

Criticisms against the book when it first appeared were mild. A Eurocentric bias permeates selections but this served to draw readers to discover (or re-discover) lesser-known and/or foreign writers. The stories, of course, also summon you to read more works by the authors and also led admirers to further explore White’s work. One man in 1993 wrote, “If Edmund White selected these stories as his personal favorites, it made me want to read and know more about him.”

As to the criticism that the collection omits black authors (other than the always divine James Baldwin), White said, “I read dozens of stories by dozens of black writers and I didn’t find anything too suitable. And I thought it was wrong to include them just because they were black.”

Robert McCrum reports, “My memory is that the book was well-received. There were some quibbles about the title – and why we had not made it Gay and Lesbian Short Fiction – but nothing serious. Having Ed White do it more or less guaranteed a smooth ride. No specific reviews stick in my mind but it was a success and I’m proud of it.”

I want to be bold and say I believe The Faber Book of Short Gay Fiction initiated a queer renaissance. The collection resurrected the reputations of forgotten authors or made readers aware that certain beloved authors like E.M. Forster, James Baldwin and Langston Hughes were homosexuals. White has rescued from obscurity men like Glenway Westcott, Denton Welch and, more recently, the too-long-neglected John Horne Burns and Jean Giono. He gave the work of Adam Mars-Jones a needed, important chance to be seen. The Faber acquainted readers with The Violet Quill, a group of seven gay creators (White, Felice Picano, Andrew Holleran, Robert Ferro, George Whitmore, Michael Grumley, Christopher Cox) formed to read and critique one another’s writing. Picano recalls the group was established because straight editors and literary agents were not being helpful with gay-themed work. As of this writing, only three members of The Violet Quill: Holleran, Picano and White remain.

*

The Faber’s wise inclusion of foreign authors generated a starburst of exploration into gay writing outside the United States. Readers discovered Machado de Assis whose anti-Realist hybrid prose lent credence to the hypothesis that he was gay. During these years, the great Cuban scribe, Reinaldo Arenas, came to prominence (in 2000 his autobiography, Before Night Falls, was turned into a film of the same name). The journals and diaries of Antonin Artaud were re-discovered. And certainly, Armistead Maupin’s story in The Faber helped bring widespread success to his Tales of the City series.

White’s elimination from the collection of one of the most celebrated gay authors of his time, Truman Capote, was due to the amazing fact that Capote never published a gay short fiction. (Interesting aside: rumor had it that a casting couch element similar to the one that existed in Hollywood for actors existed in the publishing world and that Capote’s earliest gay-themed submissions were snubbed by publisher, Bennett Cerf, after Capote refused to give Cerf a blow job. To Cerf’s request, as the rumor goes, Capote, incensed, fired back, “YOU can blow ME!” and stormed out the door.)

*

Before I tell you about the first time I met up with Edmund White’s work and with Ed, I think it is good to tell you about Miss Stanley, my kindergarten teacher who taught the class a little dance, nothing too elaborate, because we were kindergarteners. At the end of our baby ballet, she instructed, “The boys will bow (here, she demonstrated how to bow) and the girls will curtsy.” (She showed us how to curtsy). We did our tiny turns to the music and at the end, you can guess, of course, what sissy little me did. I curtsied. I was rather self-pleased until a wall of laughter and derision knocked me over like a bowling ball. If I could have crawled under the floorboards or jumped out a window, I would have.

It is small wonder I chose, then, to hide what I felt for other boys and men. It was the 1950s and ‘60s. There was no name for what we were other than the names we were being called by haters — Fish, Faggot, Fruit, Nancyboy, Nelly. Plus I was fat, homely and shy, and in the gay world — three strikes and you’re out! I related to and with no one of my kind — I did not know my kind was out there. I wallpapered my room with magazine photos of Julie Andrews and spent long, lonely hours on my bed listening to Verdi and Puccini. I dreamed I would turn into Maria Callas.

A chance encounter (though is there really such an animal as coincidence?) directed my eye to Forgetting Elena, high upon a library shelf. I was drawn to its exotic cover, to the handsomeness of the author’s book jacket photo but more so, to its rich, lush, almost tropical prose. I devoured it in a day, a Holy Grail found when I wasn’t looking for one. This was not a book I held in front of me but a mirror. Not a gay book, strictly speaking, Forgetting Elena nevertheless offered an open invitation to a gay sensibility. Ed’s sentences lay across me luxuriantly, like reclining magnolia. Ed’s writing is always deeply moving without being manipulative. In natural, unsentimental, unaffected ways, Ed manages to strike just the right pulse of a story. I find myself, again and again in his books, touched in unexpected ways. Less gifted scribes will utilize cornball, maudlin grooves to woo and unspool you. Not Ed; he knows that the root of nostalgia lies in words, not feelings. “If you get the word order right, feelings emerge — naturally.” To write good fiction, a writer needs empathy and Ed possesses it in spades. He defies the writer’s dictum to “show, not tell” and in welcome and satisfying prose he chooses to tell, and tell he surely does, lest a reader miss out on every scrumptious drop of exposition and wit. I make a beeline to the bookshop or library whenever a new title by Ed appears!

*

I was thrilled when Ed sanctioned me as his official bibliographer. Bibliography is a discipline of discovery, a detective hunt. Librarians are, by nature, archaeologists. My excavations on behalf of Ed’s work have led me on many a delightful journey — to Yale’s wedding cake-shaped, windowless Beinecke Library where dozens upon dozens of boxes holding his work await the Edmund White enthusiast. Also, to colleagues and friends of Ed: J.D. McClatchy and Timothy Young at Yale, Nancy Roche at Vanderbilt, Christopher Bram, Wilfrid Spiegelman, Steven Dansky, Tiziano Sossi in Italy, Ed’s brilliant, devoted Michael Carroll; their help was invaluable.

Google is, of course, an indispensable research tool. Yet pre-Internet materials are not always easy to find. Truth be told, one wild goose after another led to featherless dead ends, empty nests. A major assist from Patrick Merla, editor of three now-legendary gay publications: Christopher Street, New York Native and James White Review, helped me track down a fascinating packrat in Florida who’d hung on to every, single issue of Patrick Pacheco’s divine milestone of 60s, 70s, 80s entertainment, After Dark, many of which contain Ed’s early essays and interviews.

There is no exaggerating the value of Ed’s own assistance; he has opened his home, his vast personal collection, his memory palace to me, a grateful visitor. Whenever I find myself neck-deep in the quicksand of what became over 3000 citations, his is the rescue rope that keeps me from sinking.

A fervor for the bibliography led directly to the idea for a needed, new biography. And my own personal and private passion for the history of The Gay Liberation Movement in North America sees me embarking on a new project: A Pictorial and Oral History of Gay Lib.

Diligence. Discovery. Delight. This, for me, is some of the most important work I will ever do — to catalogue a great man’s work in literature, in history.

As a friend, I find Ed divine. Whether you like to walk or not (and I do), Ed will pedestrianize you — Ed loves to walk and look and talk and to have you “see”. Not even four consecutive strokes and heart bypass surgery can stop this locomotive of a man. And what a delight it is walking the wide and winding avenues of his marvelous mind. He is, quite simply, brilliant. I admire Ed profoundly, the man and the myth, the wordsmith and the punster, the raconteur and the fashionista, his endless generosity of spirit…

*

His work stands the test of time and will last and have permanent value. Ed wrote not to have the world’s prejudices against homosexuals eradicated, rather, to show others what it is like to walk in our shoes. He never peddles a false creed. He says — This is us. Take us or leave us but if you don’t like us, let us live our lives as we choose. He does not and will not accommodate convention. His honesty washes over the reader like refreshing fountain water. This truth-telling energy and output landed him in the catbird seat, paralyzed his contemporaries and gave a voice to generations of gay men. With clarity and vision of purpose, he gathered us safely under the umbrella of his bravery, revealed to us an auspicious sexual and cultural Eden that knows no bounds.

Edmund White — a true social, sexual and cultural pioneer — led us out of the dark when The Closet was very dark indeed. He marched us out into the light of Liberation to a place of not only self-acceptance but of real and a lasting pride in who and what we are.