"Winter Embrace" (2017) by Jonathan Lyndon Chase

“THEM”— gallery exhibition

There is no need for hiding in the new era of queer painting.

At Perrotin on the Lower East Side, a new survey of contemporary, figurative painting exhibits the many ways queer people address each other and the spaces we inhabit. From the looks of these paintings, queer people are safe to have sex, safe to display their bodies and safe to love openly. We have lives, not just lovers. Aptly titled “Them,” the 13 artists represented are from around the globe and speak to different walks of today’s queer walks of life. And the scenes in apartments, in bars, getting a haircut, at the beach, or in close embrace, are rather pedestrian. These subjects — equal parts fantastical and romantic — appear to be at peace occupying public space.

While the history of painting has long recognized queer behaviours in codified canvases, “Them” looks to infuse art history with a group of painters and paintings that are uninhibited by their queerness. What was previously a contextual restraint is now an opportunity to aggrandize the subject of queer life.

Before the late 1970s, and then the onslaught of AIDS, gay and lesbian painters were not explicit narrators. Queer culture could be alluded to on a canvas, but not shown. 1934’s “Greenwich Village Cafeteria” by Paul Cadmus offers a crowded parlor with all sorts of patrons, including gay men. In the right corner of the canvas, a man with red nails is on his way to the toilets. This styling, only feminine at the time, served as context to the cafeteria, providing familiarity for those that subscribed to such a “delinquent” lifestyle. Yet the naive viewer, more specifically I mean the straight viewer, may miss the hint, but still sense something awry in the scene. Those men whispering? Maybe they are too close… And that purse on the floor? It might not be that woman’s. Today, painters need not hide behind setting or symbolism to show queerness. Jonathan Lyndon Chase paints two men in close embrace. Doron Langberg shows analingus in all of its glory up close and personal. It’s wonderful to see queers comfortable enough to express themselves out from under a heterosexual veil.

“Vaquerillos en la alberca” (2019) by Ana Segovia.

“Vaquerillos en la alberca” (2019) by Ana Segovia.

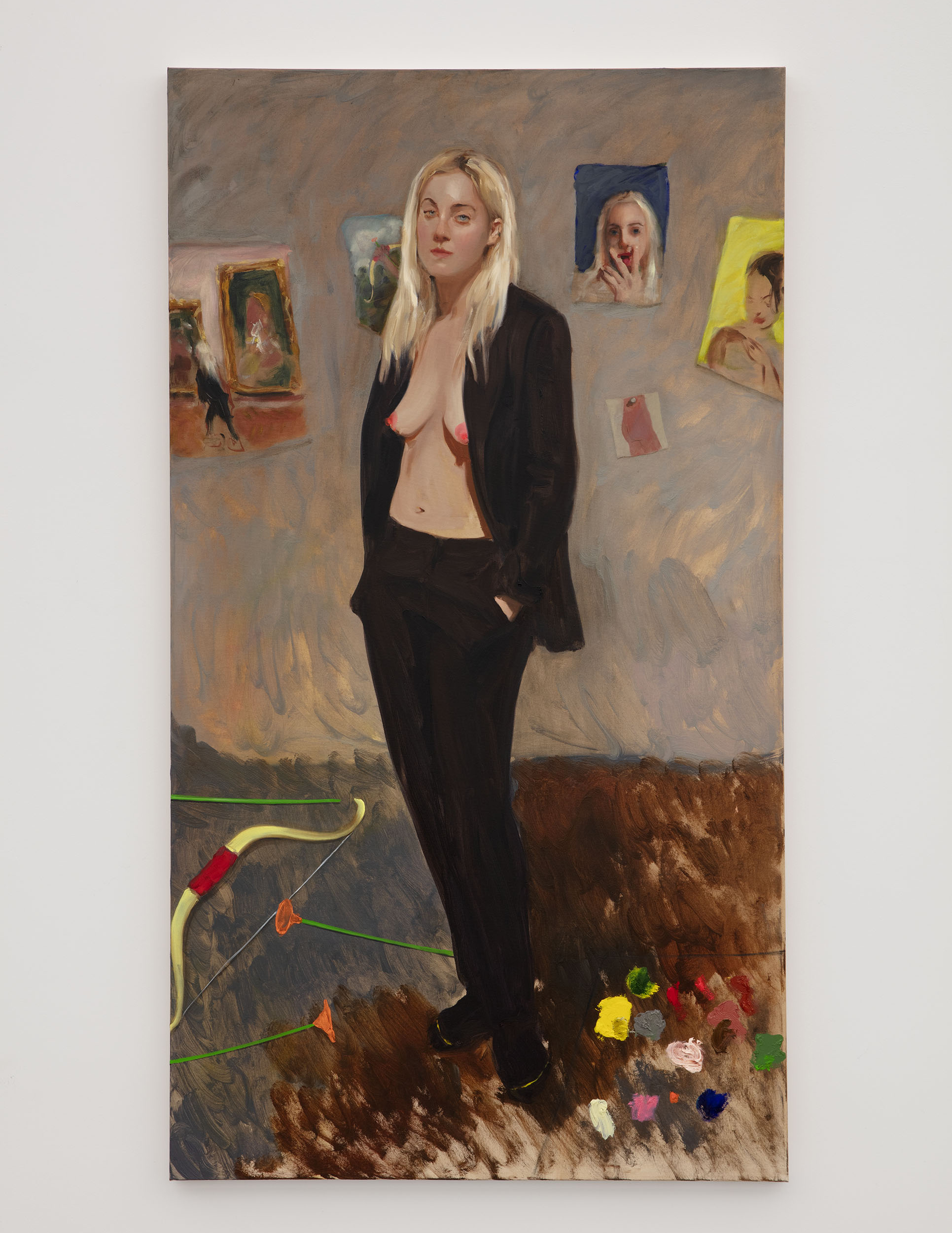

“Watching me paint” (2019) by Jenna Gribbon.

“Watching me paint” (2019) by Jenna Gribbon.

“Zach and Craig #4” (2019) by Doron Langberg.

“Zach and Craig #4” (2019) by Doron Langberg.

“The Duet” (2019) by Maia Cruz Palileo.

“The Duet” (2019) by Maia Cruz Palileo.

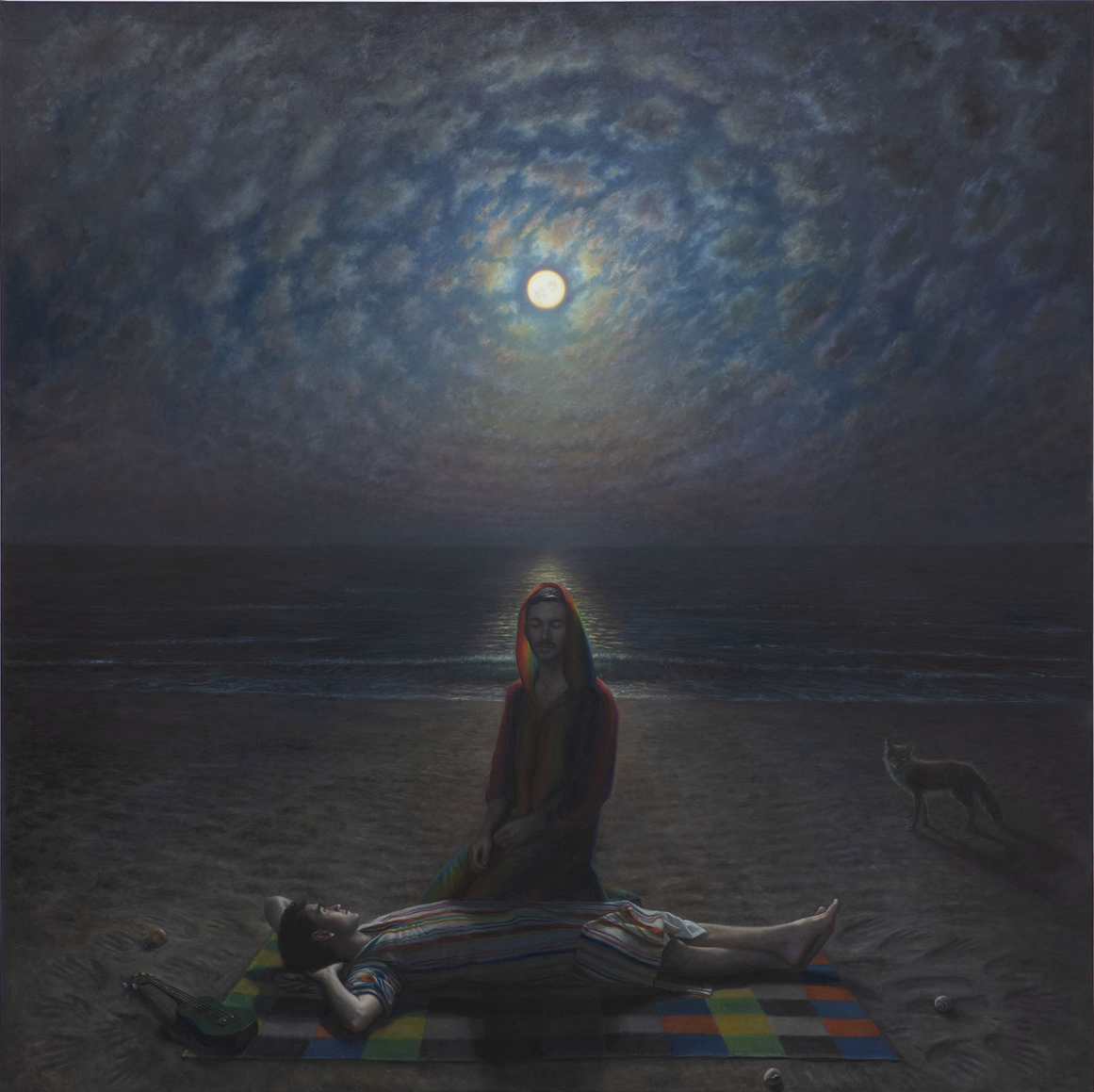

“Fire Island Moonrise” (2018) by TM Davy.

“Fire Island Moonrise” (2018) by TM Davy.

TM Davy, like Cadmus, also takes on queer space. “Fire Island Moonrise” displays the harmony found in queer locations and the safety of community. Wearing a rainbow one-piece, the central sitter in Davy’s canvas has his eyes closed. At ease with such a camp-outfit, the sitters lack of expression adds confidence to Davy’s mural-sized canvas. He doesn’t attempt distraction for the viewer. Not much is visibly at stake — two men are together on the beach. A soft rainbow pervades the scene, on the clouds, on the sand, enveloping the other subject’s face. The painting gave me great pause and a welcomed moment to reflect on the cinematic freedom of feeling safe enough to relax on the beach at night. Over email, Davy wrote to me saying he wasn’t sure if he could separate his painting from his sexuality. “Where does one end and the other begin?” he asked.

Rather than treating gender or sexuality as suggestive subject matter, Ana Segovia, a young painter out of Mexico City, uses identifiers as a formal technique to work through what she calls “trappings.” Short haircuts, blue jeans, cowboy boots, etcetera. Do they really say anything at all when painted objectively? Segovia’s subjects are neither lovers nor friends, neither butch nor femme. Ultimately, identity descriptors seem to disservice her painting, but being painterly helps Segovia explore her own queer-curiosities and synthesizes “trappings” into her palette and composition, allowing the figures she paints to exist fluidly.

“Them” is very uplifting though by no means a full range of queer painting being generated into the canon today. While it would be next to impossible to include everyone, the absence of transgender artists from such a group is disappointing, if not tonedeaf. After seeing “Them,” I wondered if we were past struggle? There is lots to celebrate at this show, and joy pervades the atmosphere, but four trans women were killed in June. 11 total this year. So, the short answer is no, it’s not easy being them, and they’re one of us. Even if most of us are comfortable, such joy is a luxury, and the fight is far from over, 50 years after Stonewall. We can learn something from all of these painters (not that the show is prescriptive by any means) yet exposure yields information, and the more the public sees the better. Nash Glynn’s self-portraits are rich in art historical reference and make the trans-body classical rather than speculative. The public would benefit from knowing her.

There is a lot of public confusion about pronouns and how they are used today. His preferences are not her requests. Their decisions do not concern you. So easily do most of us fall into the ease of the gender binary, identifying the many ways in which he and she can do this or do that. But what about them? Anita Bryant, an anti-gay rights spokeswoman, was not the brightest crayon in the box, but her crusade against the LGBTQ+ community provided fine examples of how pronouns may be used as weapons, how easily and quickly we are still othered in conversation. “What these people really want,” she said, in 1977, “ is the legal right to propose to our children that theirs is an acceptable alternate way of life.” The phrasing is not out of the ordinary for bigotry. Used here, “these people” is derogatory with Bryant attempting to generalize queers and incite public panic. They’re here, they’re queer! It is a good technique for dividing groups of people. I am not like them. You are not one of me. Nevertheless, how we are addressed in public is left up to strangers and preconceived ideas. More lies. “Them,” up through August 18th, sheds light on the truth, even if for some, it is still hard to believe.

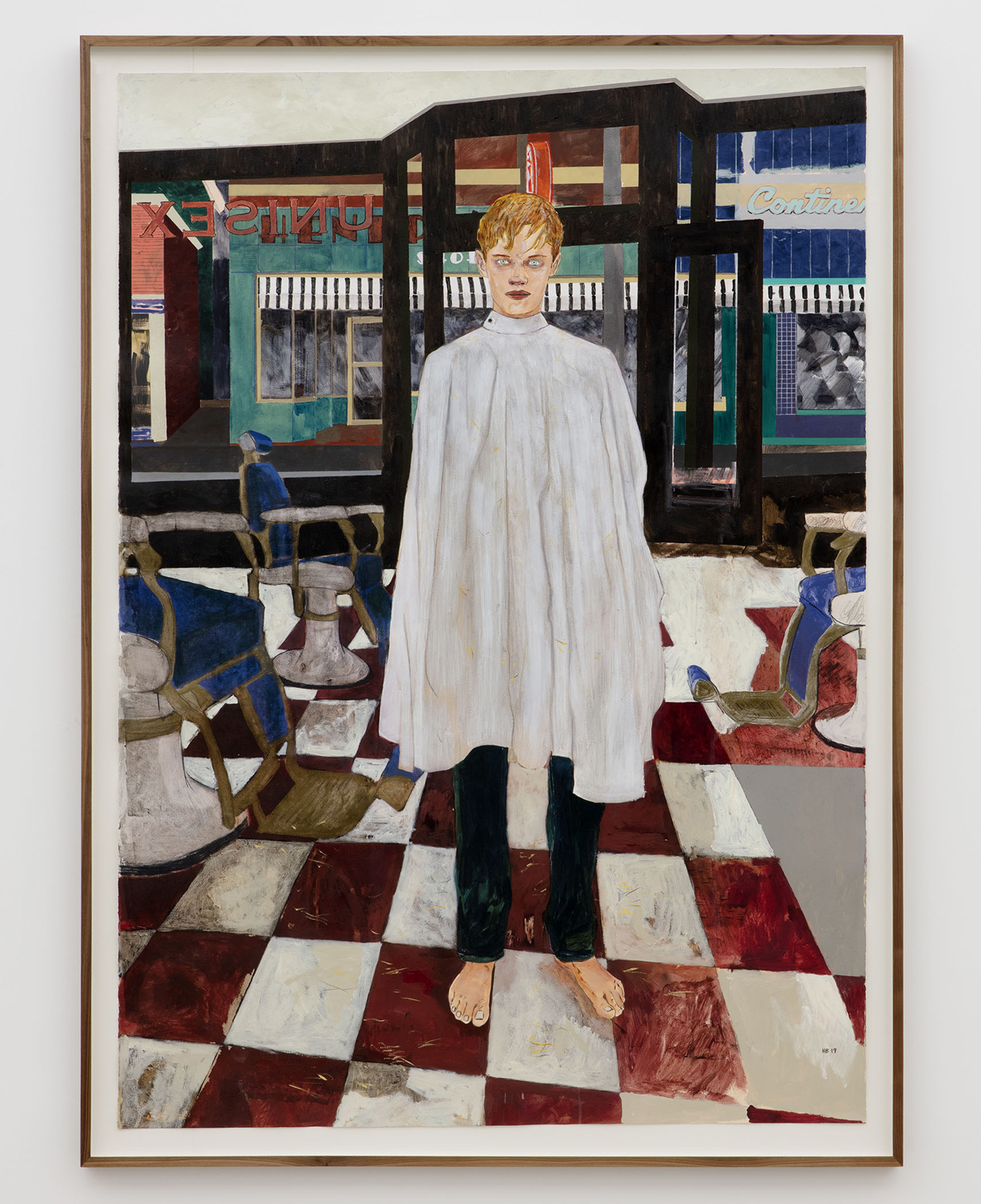

“Today Only: Free haircuts for hippies” (2019) by Hernan Bas.

“Today Only: Free haircuts for hippies” (2019) by Hernan Bas.

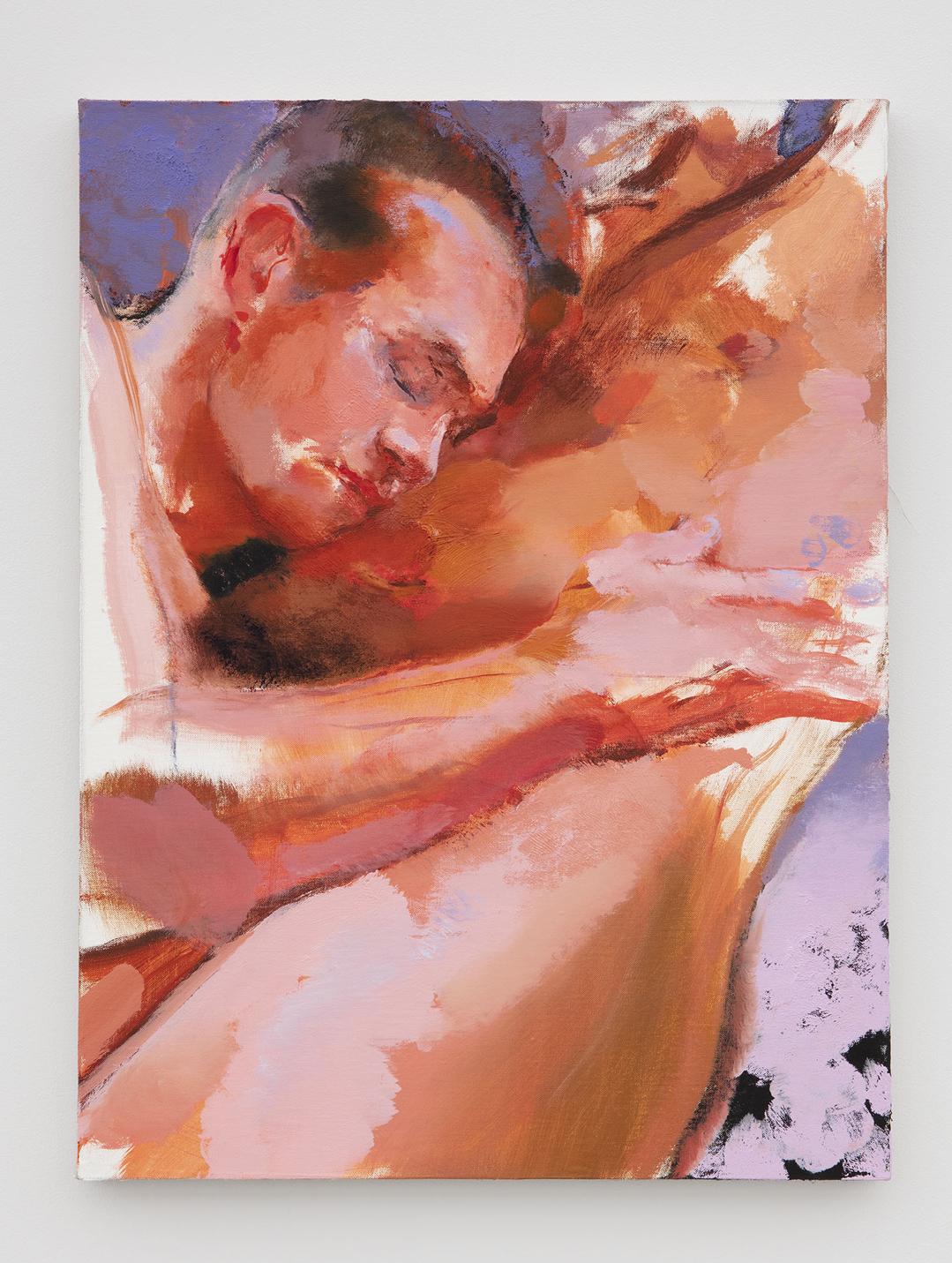

“Ian / Harvester” (2019) by Anthony Cudahy.

“Ian / Harvester” (2019) by Anthony Cudahy.

“Perfect Storms” (2015) by Angela Dufresne.

“Perfect Storms” (2015) by Angela Dufresne.

“Two Strangers” (2019) by Paul Heyer.

“Two Strangers” (2019) by Paul Heyer.

“Bed 1” (2019) by Sholem Krishtalka.

“Bed 1” (2019) by Sholem Krishtalka.

“Not myself but mixed with somebody” (2019) by Louis Fratino.

“Not myself but mixed with somebody” (2019) by Louis Fratino.

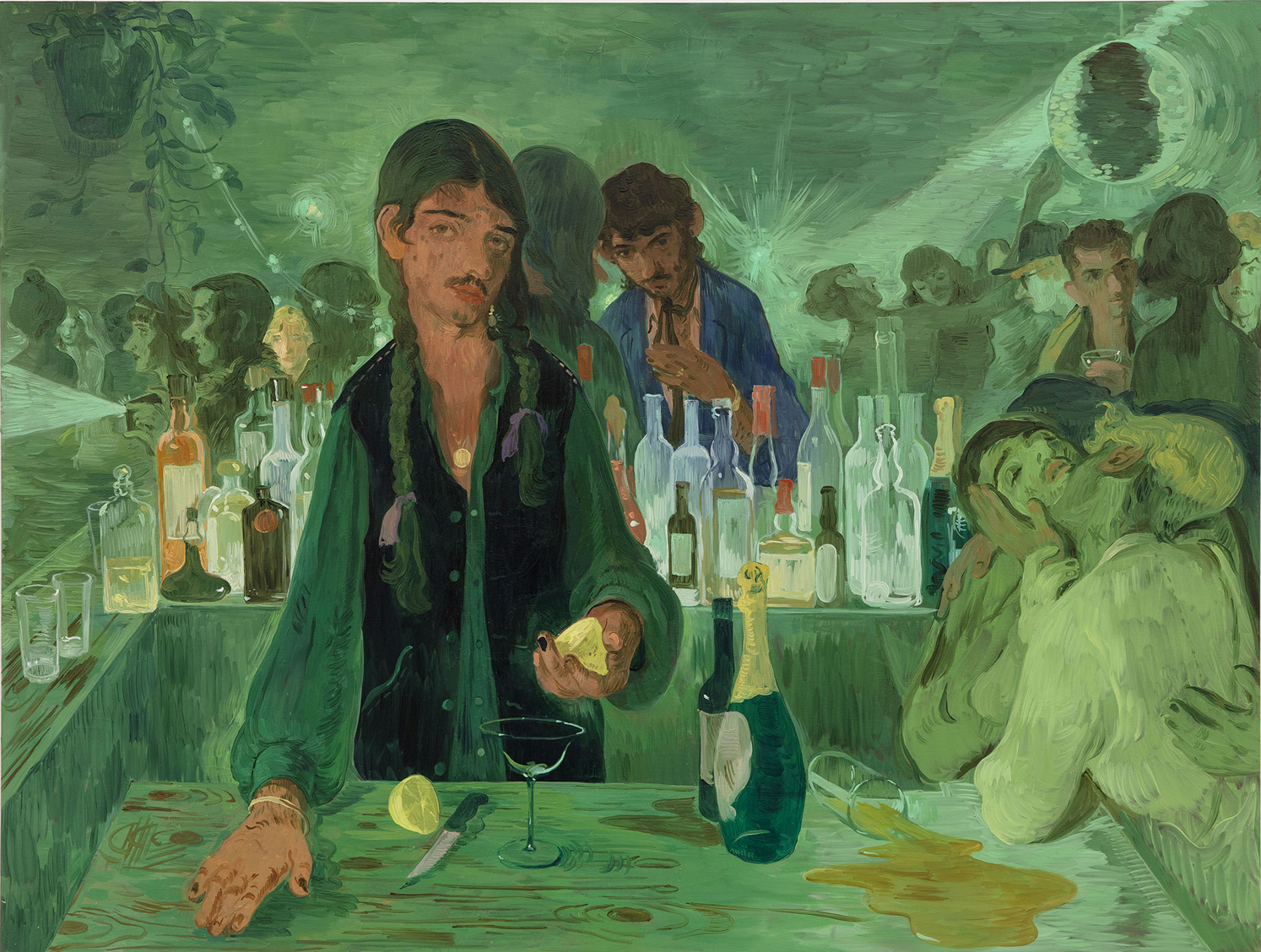

“The Bar on East 13th” (2019) by Salman Toor.

“The Bar on East 13th” (2019) by Salman Toor.