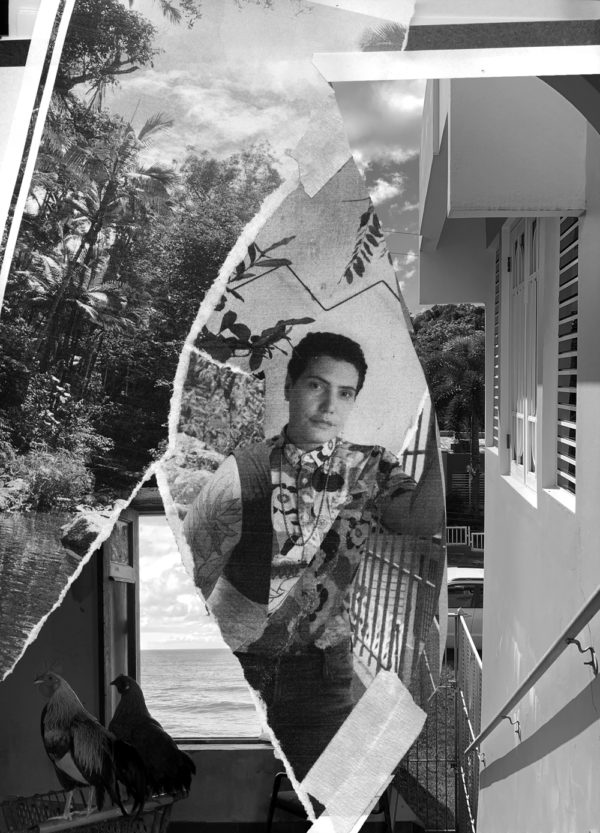

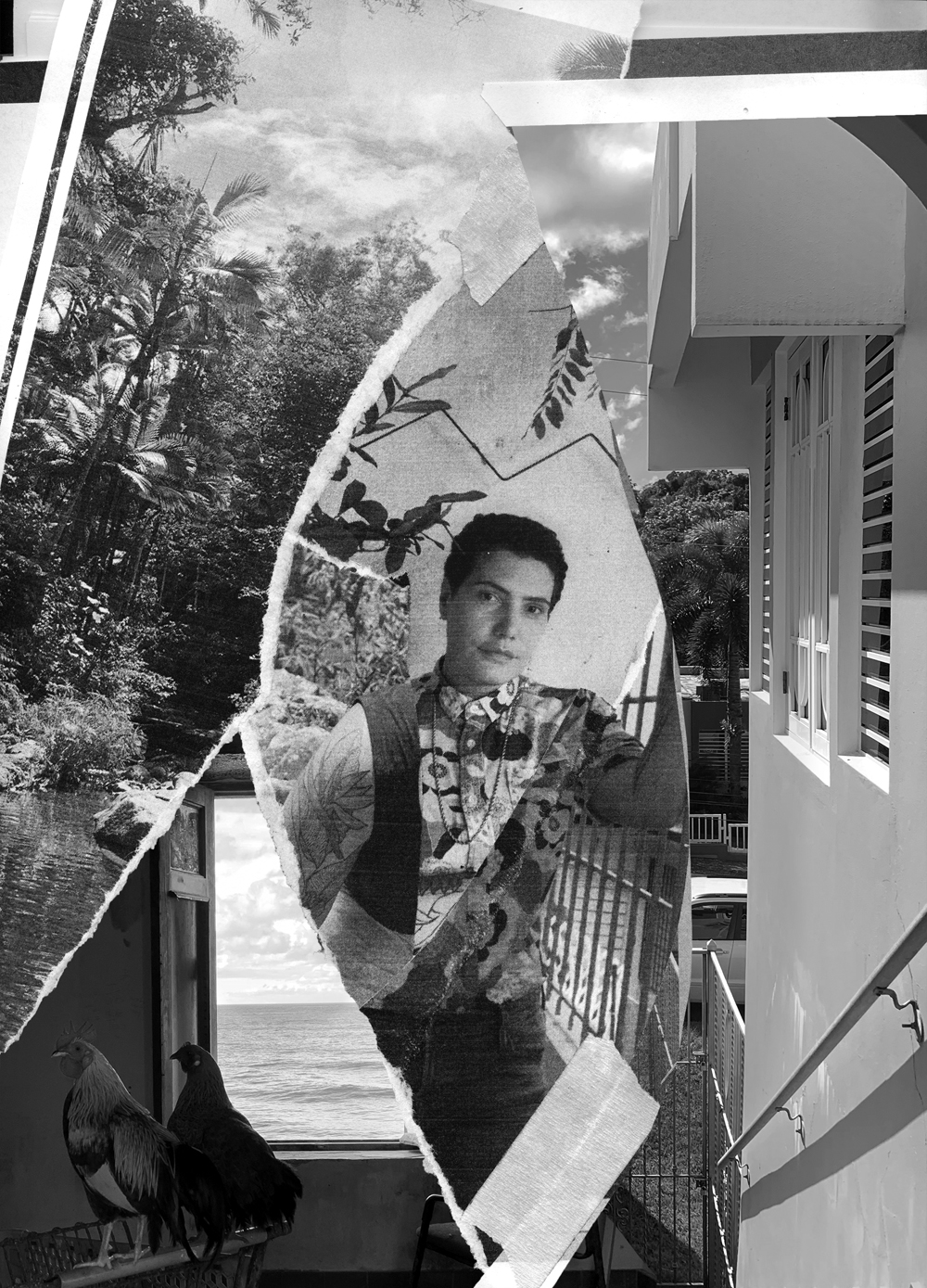

ARTWORK BY GIANCARLO MONTES SANTANGELO

Urayoán Noel and Raquel Salas Rivera

This past November, the Friday after Election Day, We spoke with Urayoán Noel and Raquel Salas Rivera, each a Puerto Rican poet, scholar, and performer in their own right.

Urayoán called from the Bronx. His seventh book of poetry, Transversal (forthcoming), reconfigures the border between Spanish and English to create new possibilities of their arrangement, fusion, and division. Raquel called from Santurce, Puerto Rico. His eighth book of poems, While They Sleep (Under the Bed is Another Country) (2019), describes in Spanish and differently in English the grief, rage, absurdity, desire, and numbness that are the colonial relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States.

We are grateful to both poets for sharing original poetry with us. Read on, where Raquel and Urayoán discuss the historic shifts in today’s Puerto Rico, the island’s anarchist history, finding places to grow, loving Philadelphia, remembering Sylvia Rivera, and building a lineage from the cracks.

Maybe we could begin with an overview of what’s going on in Puerto Rico today.

Raquel: We still have the Oversight and Management Board, la Junta as we call it here, which goes above the legislature and the governor. This election follows a mass movement of a size we haven’t seen in recent history. People have compared it to Vieques. It seems to have broken through a wall, and that’s undoing a belief that has existed for a long time. I grew up hearing we were just too divided as a people, that there was no way we could come together for something. But Ricky Renuncia, literally in a day, in a night, undid that, because people spontaneously came together. That changed what many people saw as the horizon of political possibility. Even though it didn’t necessarily change a lot structurally, in terms of our colonial status, what it did more than anything is imbue us collectively with a sense of, “We have some power and impact on who governs.” I don’t know if that’s necessarily true, but it’s a step toward relying more on our collective strength and less on colonial structures.

Urayoán: Puerto Rico has an anarchist history, with a broad historical context: things like the Vieques protests in the early 2000s, the Universidad de Puerto Rico student strikes. Ricky Renuncia was crucial, but it built on a long period of investment and direct action that also responded to the failure of the two-party system, the bogus politics that it represented, and the entrenched political elites therein. For me, in the diaspora, you know we’re taking notes — thinking how to honor the direct action component and not reduce it to an electoral bottom line and other possible narratives of social movements.

Raquel: Absolutely. In Ricky Renuncia, a lot of the chants came out of the 2005 and 2010 strikes at the University of Puerto Rico. Many were chants that were common to the left. It was very impressive to see that being chanted across a spectrum of people that hadn’t necessarily participated in movements like that before. It’s very much an indication of that work that had been building.

How does intersectionality play into this movement that’s been building?

Urayoán: I’m thinking of the way that these elite legacy parties are white, right, straight, and cis. And in the case of the PIP [Partido Independentista Puertorriqueño], kind of bourgeois. The question of intersectional politics is important cause all this coincides. The eco-decolonial politics of Vieques happens alongside Afro-Puerto Rican, queer Puerto Rican, and trans Puerto Rican activism. You can’t reduce or collapse one thing to another, but it’s significant that people who have been organizing and fighting different battles are finding common cause in that the existing legacy structure has not made room for them. We’re seeing an attempt to reconfigure these political horizons to account for all the gains that have been made by the struggles to represent marginalized Boricua experiences and histories.

Raquel: The irony is that Partido Independentista Puertorriqueño [el PIP, the Independence Party] has been around for a long time, so it’s been very strange to see it suddenly become a thing. Part of what’s really difficult with el PIP is it symbolizes precisely, for me, that gap between a Black and brown working class in Puerto Rico, and a very kind of independista, nationalist sector that doesn’t examine its classism or racism or its investment in capitalism, you know? They would rather invest in this political party that has been natimuerto for so long than make any connections with a large sector of the working class that votes for statehood. It’s weird to watch it grow. I don’t have any faith that they have changed. A while back they were saying that when Puerto Rico became independent, it should become part of the European Union. Which was the most absurd thing I’ve ever heard. I’m sorry, what? I think any plan for the future that looks like that is gonna fail.

What have your own experiences been navigating your identities in America?

Raquel: Coming back to Puerto Rico, what I learned in Philadelphia was very useful to me. The people I learned most from were young queer activists in this scene that’s been happening in Philly for a while. Part of it is a result of ACT UP, indirectly, from the years ACT UP was in Philadelphia. The Mazzoni Center is in Philadelphia. Even with all its problems, the Mazzoni Center is a place that trans people go to, and even move there to go to, because they know they’re going to have a little more medical and structural support for their transition. Being around so many trans and queer folk creating these alternative spaces and scenes for artistic production really freed me up. Philly is an exceptional place.

Urayoán: I’m thinking of, in places like the Bronx where my New York family is from, that whole, “Do you choose queerness or do you choose being Boricua?” Thinking about the particular ways those two intersected was really important to me. We’ve got people like Luis Carle, the photographer, and scholars like Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé who were thinking of queer diasporic literary traditions and formations. Eventually, I was trying to figure out my own place at spaces like the Nuyorican Poets Cafe. I had the split personality, where I was a Ph.D. student by day and reading poet at night, trying to figure out what spaces of queerness were there. Someone like Emanuel Xavier’s work early on opened up the space. It was these scattershot geographies that kept sedimenting one onto another. The South Bronx here, Loisaida there, Brooklyn there, just piecing together.

Raquel: Speaking to healing that either/or thinking, you know, “Where do I get to be gay and where do I get to be Puerto Rican?” The crossroads of coming back to Puerto Rico has honestly allowed me to, sort of, be… It’s healed some things for me, and has played a key role in my choosing to begin T in the middle of a pandemic. Despite having so many more resources in Philadelphia, this is the place that I wanted to start T. I think that is telling… Or maybe not, you know. [Laughs]

It is telling; it’s beautiful you found a place to heal. What else has felt restorative or inspirational in this moment?

Urayoán: I’ve been thinking a lot about Sylvia Rivera lately, her amazing stories, and her own whole relationship to Latinidad. Getting kicked out, and being Boricua and being Venezuelan… I don’t know; for some reason, her voice is ringing through me right now as folks are having all these reductive conversations about Latinidad. About the bodies that are on the line. Sylvia is somebody who had to take all that, and then imagined other. Sylvia’s helping me connect what’s happening.

Raquel: Academia helps us sometimes find those lineages in the cracks. Not because other academics necessarily teach us — sometimes they do, but rarely. Mostly because between the texts we find something, and we build a curriculum of our own that helps us understand ourselves and the world. I do think institutional access gave me that. Or, at least, a library.

Raquel Salas Rivera photographed in Santurce, Puerto Rico. November, 2020.

Raquel Salas Rivera photographed in Santurce, Puerto Rico. November, 2020.

analysis of a rose as sentimental despair

by raquel salas rivera

i kissed you dykishly on the train

and they stared.

in their stare, i had another life:

beaches on rocks

and water. i

n our kiss, we had this life:

rocks in the sea

and sand.

analysis of a rose as sentimental despair

by raquel salas rivera

te besé patamente en el tren

y nos miraron.

en su mirada, tuve otra vida:

las playas sobre las piedras

y el agua.

en el beso, tuvimos esta vida:

las piedras en el mar

y la arena.

Urayoán Noel photographed in Randall Island, New York City. November, 2020.

Urayoán Noel photographed in Randall Island, New York City. November, 2020.

Postscrypt

by Urayoán Noel

When capitalism is a virus

That’s knocking on each barricaded door,

We summon all the dead from the long war

To weaponize, silence, and hellfire us.

Corona? Our bodies crowned, desirous,

A furious light too brilliant to ignore.

We won’t let them erase us anymore.

Our skin, a stateless scroll, dream papyrus

That maps hidden shores in rhymed polemic.

We heed the earth and let it legislate.

Capitalism becomes its own pandemic.

We pledge allegiance to the night’s estate,

The dark seed in us, fractal residue.

We pledge allegiance to the flagless crew.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 13, get a copy here.