From Top: BILLY MILLER & JONATHAN BERGER PHOTOGRAPHED BY GAYLETTER

Billy & Jonathan on Bob Mizer

A conversation with the curators of Mizer's latest exhibition

A few months ago, we visited the new exhibition for the late“beef cake photographer” Bob Mizer titled Devotion: Excavating Bob Mizer at 80WSE Gallery. It covers several chapters of the artist’s illustrious career that spanned 5 decades, dealing with the male physique. It’s curated by Billy Miller and Jonathan Berger, in collaboration with Dennis Bell of The Bob Mizer Foundation. We loved the show so much that we decided to have a long chat with the curators Billy and Jonathan.

How did you two get involved with this exhibition?

Jonathan Berger: Billy, maybe you should talk about your history with Bob Mizer.

Billy Miller: I’ve been aware of Bob Mizer since I was maybe about 12 years old and have been fascinated by his work for most of my life. I’m from Detroit and when I moved to Chicago I discovered a publication called Straight to Hell, edited by the infamous cult figure Boyd McDonald. When I moved to New York in the ‘80’s, McDonald and I became close friends and I subsequently became the editor and publisher of STH. About a third to half of STH covers were Mizer photographs and Bob’s studio Athletic Model Guild was advertized in every issue. So one of the first things I wanted to do was meet Mizer, and I went to California a couple of times and did meet him and had a long-distance relationship with him via letters and occasional telephone conversations. This was all pre-internet.

So you guys dated?

BM: No, when I say relationship, it was a strictly a professional relationship. He and Boyd McDonald died within a year of each other, and Bob’s estate was sort of in limbo for quite awhile. Then a few years ago, I found out that a guy named Dennis Bell had acquired the estate and I contacted him about advertising the revived AMG in STH, and we also talked about doing a related art exhibition. The first show was in Berlin and that turned out well, so then we did another exhibit last year at Invisible Exports gallery on the Lower East Side. During the run of the show, former LA MOCA director Jeffrey Deitch came in and bought a couple of pieces for the museum’s collection and that spawned a large exhibition of Mizer and Tom of Finland artwork that was recently on view there. I’d been talking to Jonathan about the work for quite some time and then he became the director of this gallery… and well, perhaps he can speak to you about that.

Yeah, so if you could answer the same question. You guys were friends obviously before this?

JB: Yes. I think Billy and I met for the first time in 2006 through Vaginal Davis who we’d both known for awhile. Billy and I have similar sentiments about the art world and have a shared interest in people we think of as maybe visionary or highly influential but who are either misunderstood or haven’t received the recognition they deserve because they’re operating for one reason or another outside of systems that could validate them. I knew who Bob Mizer was but thought about him the way most people do: through a sort of beefcake-only lens. Then I began to appreciate other work that was being discovered which is much more complicated and strange, and personal. And so when I ended up with this job here I thought it’d be interesting to collaborate on a project such as this – and I also thought it’d be great since this gallery is a special situation where it’s not a museum, not a normal non-profit gallery, and at the same time not a commercial gallery either. 80WSE is attached to a university studio art program and yet the space is much bigger than similar programs at other institutions. So, we’re in a unique position to do shows that could not happen anywhere else.

BM: When a gallery like this or a museum validates something, then all of a sudden it changes everything. The show in LA is the first museum show of Tom of Finland and Bob Mizer and ten years ago they would have probably laughed at idea, but now it’s happening. It takes someone to be the first one, to open the door: and in this case, it was Jeffrey Deitch and Jonathan Berger who decided to take that step.

Bob Mizer: Untitled [Acrobats With Child], Santa Monica, California, 1946.

Bob Mizer: Untitled [Acrobats With Child], Santa Monica, California, 1946.

Bob Mizer: Tony Rome & Ron Nichols, 1971.

Bob Mizer: Tony Rome & Ron Nichols, 1971.

Just to clarify. When you said you run the magazine Straight to Hell and you advertise the work, does that mean you feature the work?

BM: Yes we do. Bob founded his studio in 1945 but it’s only been since his death that he has really emerged as an individual artist. During his lifetime, most people familiar with his work weren’t connecting it so much with a name but with his company, AMG, and the various products that he put out. Bob was an outsider in the sense that he wasn’t a part of the art world or the photography world per se. But now 20 years have gone by since his passing and folks are beginning to look at his work and legacy in a new light.

That’s interesting, because we just saw a show on Jim French’s polaroids, and he repped Colt Studio.

BM: Yeah, that’s what I mean. Bob produced a wide variety of imagery and even people who are familiar with the work are surprised by a lot of the material in this exhibition. When we were installing the show, a guy who was coincidentally one of Mizer’s models asked, “Who’s work is this?” So that just shows you the range.

Who came up with the title for the show ‘Devotion: Excavating Bob Mizer’?

BM: Jonathan.

JB: I came up with the word “devotion” but then the “excavating” part we decided on together. The last part of the title refers to the fact that we’re processing a significant portion of the estate for preservation: and relates to the kind of images we’re showing – namely, material that is being discovered which was not known about until very recently. That process continues throughout the run of the exhibition. There’re people in here working every day for the entire run of the show. So when you come, you see the images but you also see people working, scanning negatives, cleaning transparencies and doing a variety of projects.

Yeah, we found it revolutionary. We thought it was a great treat to see that.

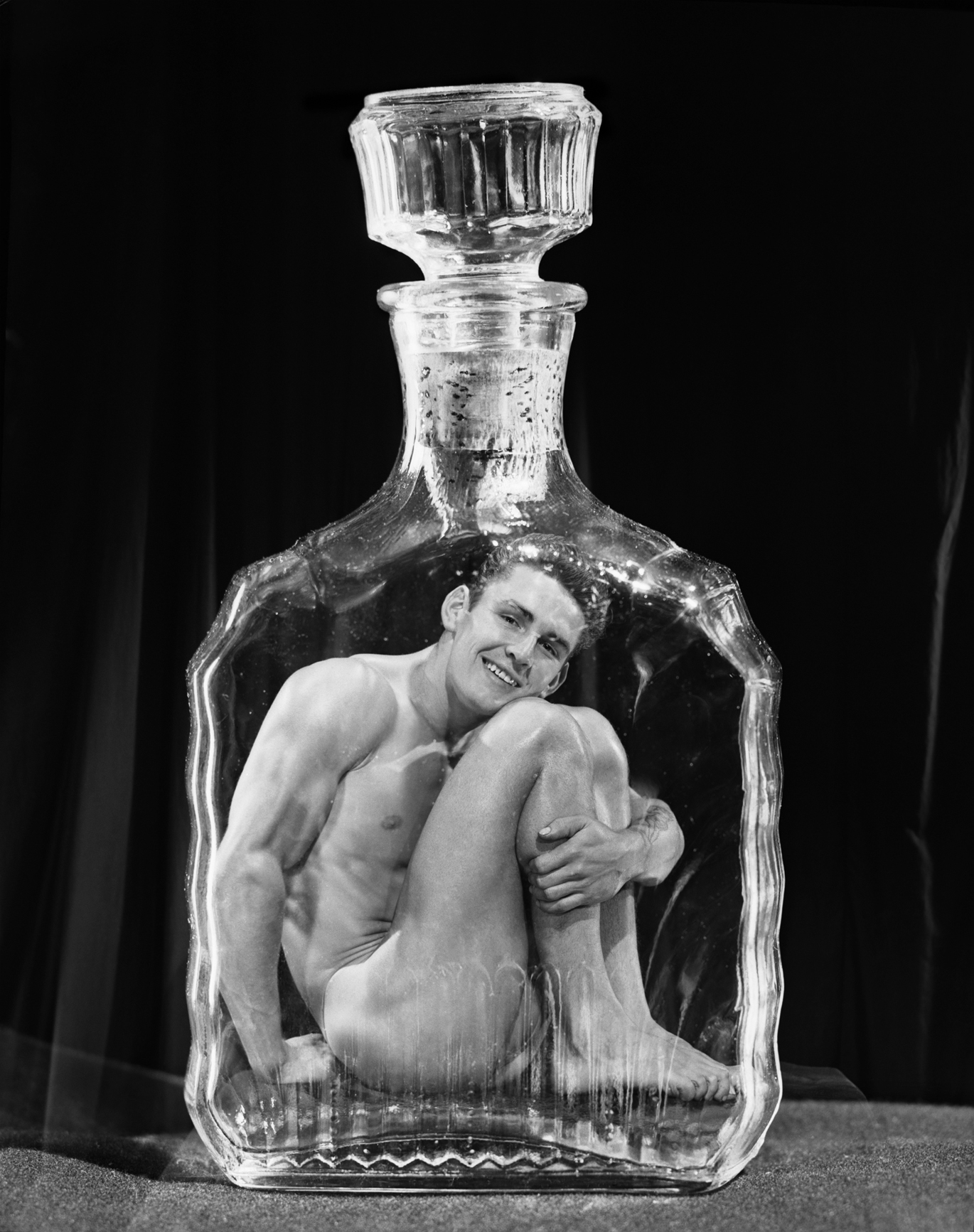

Bob Mizer: Leonard Chambers [In Flask], Los Angeles, 1950.

Bob Mizer: Leonard Chambers [In Flask], Los Angeles, 1950.

How do you think that impacts the viewer’s experience of the show?

BM: I’m not sure if I’ve ever seen a show like this. And what we’re trying to get across, is that this is just part of a process. It’s a huge collection: with over a million and a half negatives, thousands of films and other archival materials. I couldn’t go through all that in my lifetime. We’re just trying to make people more aware and spark an interest in it because a lot of people may think because Bob’s been around for so long, and his pictures are all over the place, they probably think everything has already been seen. But we’re like, no way, you haven’t even begun to see it yet.

So this show is just the tip of the iceberg?

BM: It’s totally the tip of the iceberg. This doesn’t even count. I mean, a million and a half? This isn’t even an umpteenth of it.

How much of it did you want to archive by the end of the show?

JB: There are people in here working everyday but it’s not really about how much we get done. As a gallery that is in an academic institution, it was important for me to convey that we’re offering a service and contributing to this effort. So we’re not just showing the work, we’re investing in the preservation of his legacy. I think it’s more about that. Obviously we want to get as much done as we can but we want to send everything back in a better state than when it came here. And we want to participate in some way in the reevaluation of this important but largely overlooked artist.

BM: Another thing is we were very adamant that no one comes away from this show with the idea that this is a retrospective. Which is why we’ve focused only on this one aspect. I don’t even know if a real retrospective is possible. We want to insure that there will be ongoing opportunities to explore other aspects of Mizer’s work and his cross-cultural influence and connections.

JB: I was thinking about this the other day and it’s interesting and I would say significant that all three of the people who worked on the show: myself, Billy, and Dennis are all gay and yet we were are all really adamant that the show not be something like, “Bob Mizer: The Gay Icon”

BM: Yeah, I fight against it but at the same time I wonder if people misunderstand because people keep coming back with the same ol’ Gay, Gay, Gay stuff.

JB: And straight people, too.

BM: It’s lame and sort of a moot point. Does anyone say, “Gay Artist Andy Warhol”, or “Gay Writer William Burroughs”? It’s like, duh, does that even need to be said? Or does it need to be said over and over and over again? My hope is that at some point you’d not have to keep saying that… where you could go beyond that and look at other things.

JB: It’s also just reductive. Part of what’s been interesting to me about this is that when I send the images to people -and I’ve worked on projects that have been really difficult or transgressive- the response to this selection of pictures is that, considering people’s backdrop of knowledge about Mizer, they tend to have a really hard time with it. A lot of people are like, “What the fuck am I supposed to do with this range?” Some people don’t want to accept that one person could be that complicated. It’s like you have this beefcake/soft-core gay porn business on the one hand, and then all these different sorts of images which presumably point to an even greater variety of imagery: but we live in a society where -especially with artists people still want you to do just one thing. They want to understand you as someone that they can put in a box or reduce to something that’s understandable. I think our society is naturally resistant to complexity, and that’s just the way it is.

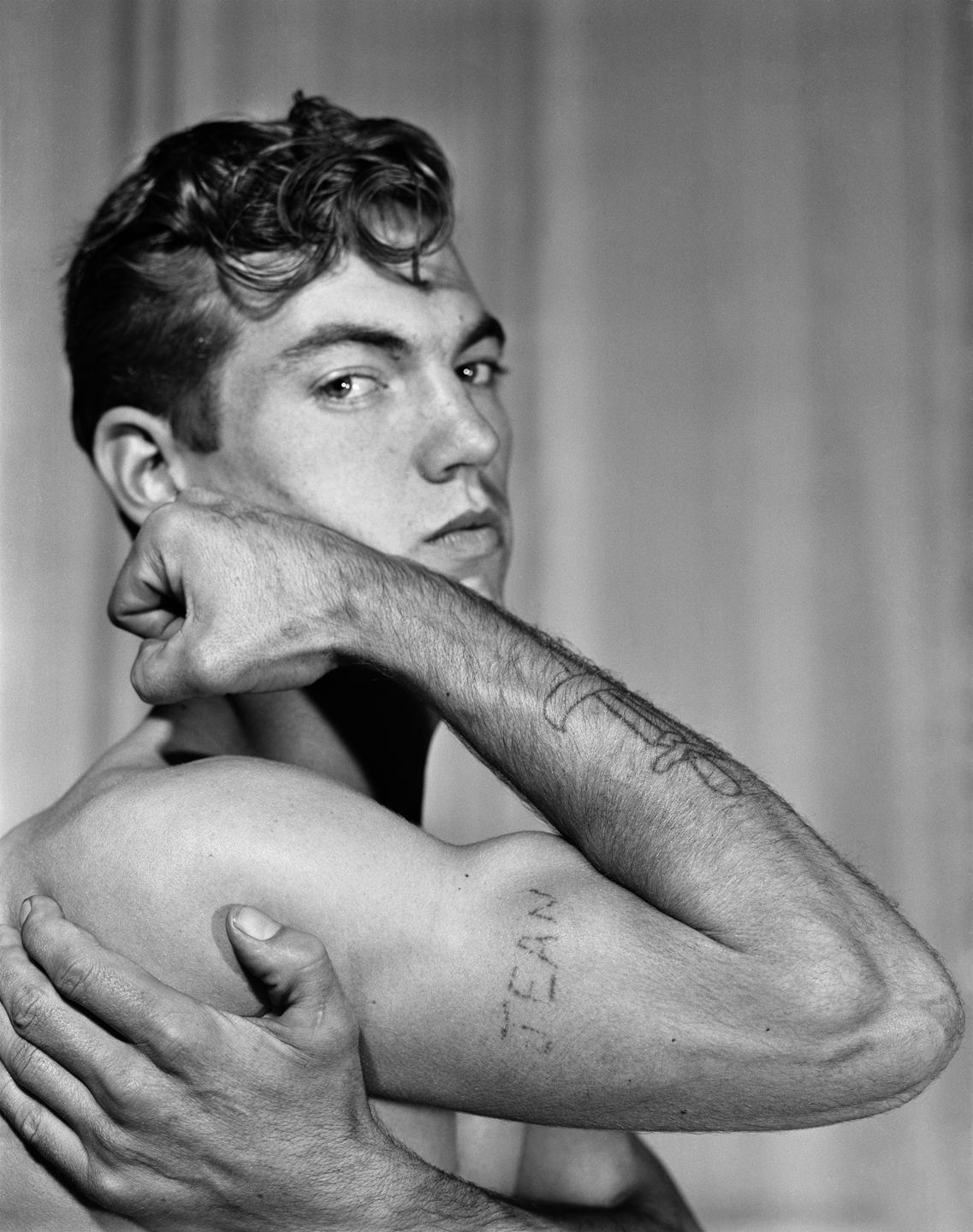

Bob Mizer: Beau Rouge, Los Angeles, 1954.

Bob Mizer: Beau Rouge, Los Angeles, 1954.

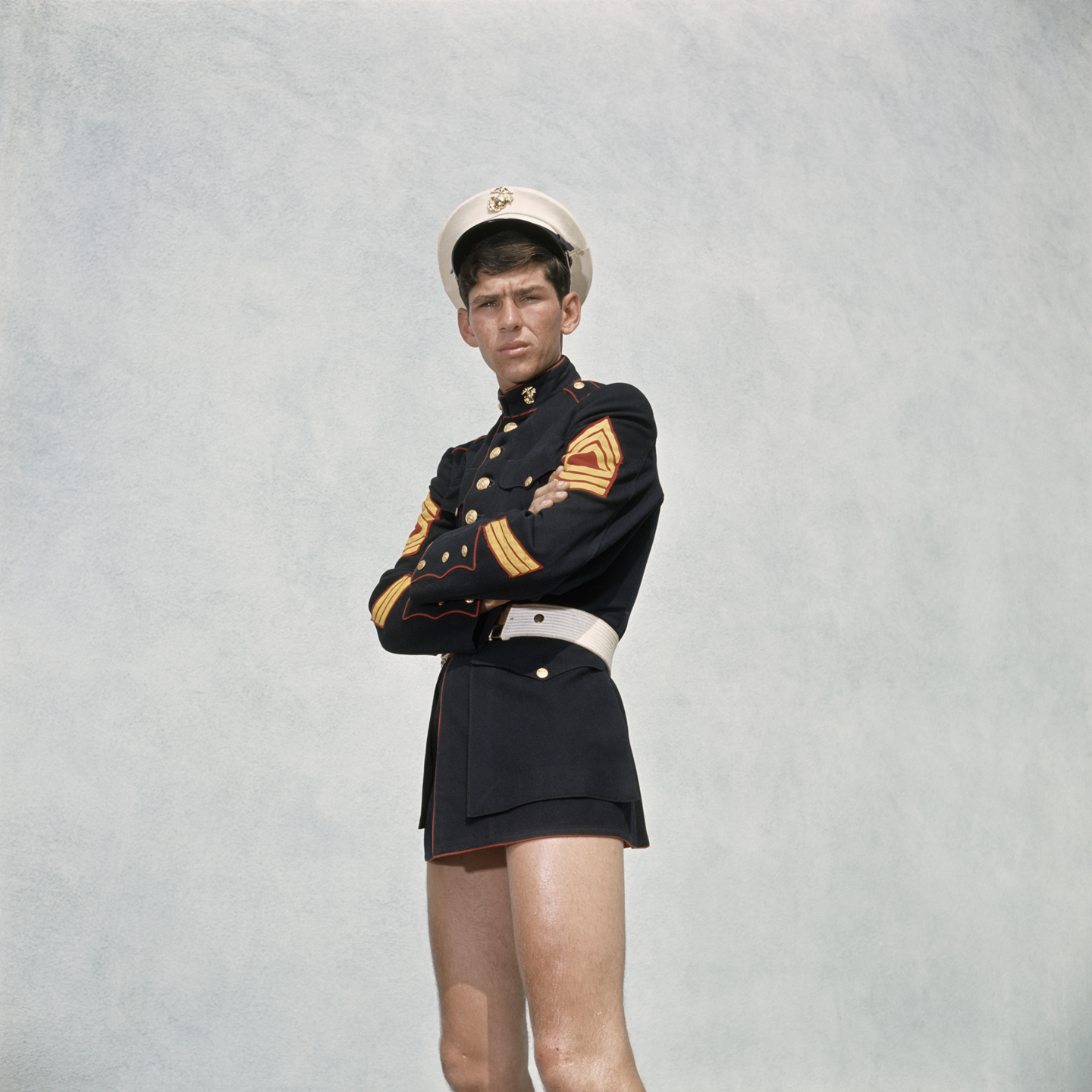

Bob Mizer: Unknown Marine, 1973.

Bob Mizer: Unknown Marine, 1973.

BM: The more you understand the more these pictures start to make sense. But if you don’t know anything, you’re like, what? Why should there be a Nazi standing there with a dog against that weird incongruent background? What is that about and why did somebody even take a picture like that? That’s the thing with a lot of these images. It oftentimes doesn’t conform to the modern idea of what porn is or what “art” is. I mean, why would anyone bother with all that artifice and specialized lighting. This work pulls in history. To really understand it, you need to educate yourself on so many things that went into the making of it all. At the very least, Bob was a major player in the history of the Sexual Revolution.

Why do you think it took so long for Bob Mizer to have his first institutional solo show in the United States? Is this a good time for it?

JB: That’s a complicated question because much of it wasn’t know about until relatively recently.

BM: It’s really been in the past several months to be honest and is reflective of a lot of things. Homophobia is part of it and also the way the art world now is different than it was even five years ago. It’s sort of like what I was talking about earlier, once a door opens, things change. I’ve told young people that Mizer’s studio was founded in 1945 and then they ask me what gallery represented him? Er, you really think a gallery or cultural institution would be interested in this stuff in ’45? I mean, come on. The context that made this show possible has only just started to appear. There are things that have been happening in the world recently that have been conducive to talking about this and other material. Popular as he was, Bob Mizer was an outsider so it’s only now that the art world is able to consider him and that there would be a larger audience for his work. Also collectors are different than they used to be. Institutions are just starting to do shows that

Did Sam Wagstaff (Mapplethorpe’s lover and patron) have an interest in Bob Mizer’s work? I would imagine he would have been really into Bob.

JB: I was thinking about that and I really don’t know. Even though Wagstaff had a really deep appreciation of vernacular and anonymous photography and all that, AMG was seen functionally as pornography and kitschy, cheesecake-y, mid-century. So there’s a part of me that thinks Wagstaff wouldn’t have had an interest in him – especially since he couldn’t have know about the variety of material that’s coming to light now.

BM: It depends on how old you are too. It’s a generational thing. I was at this thing with my friend Dennis Bell and someone said something about Mizer being tame in the 50’s. And we were like, no! If you look at the context of the 1940’s and 50’s, any of this stuff would have blown most people’s minds. He was revolutionary and was really pushing the boundaries. Bob went to jail for this imagery in an era where just doing anything outside the norm was outré. I mean when I was growing up this was just unspeakable in normal public situations. You would never go to a museum or a gallery and start talking about dicks. It just wasn’t done. So now that the whole landscape has changed, people look back and apply this very recent template: but you really can’t do that. The thing about the world now is you can take all of these things and you line them up next to each other and they look like they’re all the same, but it’s important to have an understanding of the historical context.

JB: Just to go back to your question about the climate in which this is happening now… there are all these artists, and a lot of this is only really coming to the surface now, but there are a lot of artists who consider him an influence. David Hockney has a connection to Mizer, Jack Pierson, the photographer, was both photographed by Mizer and very influenced by him. I don’t know if formally Collier Schorr was but I would think that she’s certainly aware of him, which often is the case with these marginal figures because artists often are more avid researchers than people that just consume art. I think his influence has trickled down into contemporary art through in various ways.

BM: Also, because he was an outsider, it wasn’t taken seriously. People still don’t take porn seriously. You can borrow from it and do whatever you want you want with it but you don’t have to acknowledge it because it’s not real and not really part of the official “art world”. I see Mizer’s obvious influence on Warhol and photographers such as Robert Mapplethorpe and especially Bruce Weber, in collages by Jack Smith, etc, and as the source material for painters like David Hockney, Francis Bacon and all these others and yet when I point that out people will discredit it because Mizer is not seen as fine art so it doesn’t count.

Do you think that’s one of the reasons why this work wasn’t archived before?

BM: It has to do with money and history and all kinds of things.

How do you think Bob Mizer’s work has influenced the aesthetic of the male physique – and, who do you think he’s influenced?

JB: Horst?

BM: I don’t have any direct proof but I’d say George Hurrell for one. It’s hard to know because that was just the standard of the day and a lot of it you have to go back further because they were imitating paintings and things like that. If you had gone to even a normal photography studio in the 1930’s and ‘40’s, they would be doing some approximation of the same sort of lighting but with different levels of skill. There were certain standards. But Bob’s most experimental period, I believe, was in the 1950’s when he came up with all sorts of effects such as rear projections, double exposures, and all that great variety of backdrops and costuming. The ‘50’s were really his heyday because he was ahead of everything. He was at the head of an emerging homosexual vanguard movement in art and publishing and was going off in every direction. And he was very successful at it so I’m sure that motivated him more and more. He had a long career and was innovative throughout all of it.

BM: There’s a lot of other people that you maybe wouldn’t have heard of before that I see. His sort of protege was a guy called David Hurles, “Old Reliable,” and he’s still around. He’s the direct sort of inheritor of Bob’s stuff. He used the same models and everything. He was very different than Bob but also like Bob.

Bob is an earlier generation, you guys probably don’t have any specific record of who influenced Bob?

BM: Oh, I know. I don’t have any record or anything, but like all photographers of his generation he was influenced by Hollywood, and he lived in LA. So there were Hollywood-era photographers, like… I can’t think of his name, but he did all of these glamour photos of all the movie stars of the 30’s and 40’s.

JB: Horst?

BM: Horst is one of them, but…

George Platt Lynes?

BM: No, not George Platt Lynes. Hurrell… Do you know Hurrell? George Hurrell. It’s hard to know because that was just the standard of the day, and a lot of it you have to go back further because they were imitating paintings and things like that. But Bob learned his craft, a typical photographer’s craft which people don’t learn anymore, but if you had gone to even a normal photography studio in the 1930’s and 40’s, they would be doing some approximation of that same kind of lighting with different levels of skill. But there were certain standards. But Bob’s most experimental period, I believe, was in the 1950’s where he did all this stuff with rear projections and double exposures and costumes and layering of things. The 50’s was really his heyday, because he was ahead of everything. He was at the head of this vanguard of homosexual movement and art and publishing, and just going off in every direction, and he was very successful at it, so I’m sure that motivated him more and more. He had a long career, and he was innovative through all of it, but I think the 1950’s was really when he was ahead of the pack.

Did you ever meet Bob?

BM: I did meet him. Although he was really good-looking when he was young, he looked like a farmer when I met him. He wore overalls or suspenders and had really leathery skin.

Are you guys working together on any other queer-centric projects that we should know about?

BM: Well, I’m coming out with a new Straight to Hell issue.

Ok, good. It’s been awhile, right?

BM: It’s been a couple of years. Also, we have seminars coming up…

JB: During the last two or three weeks of the show we’re hosting a series of public programs. The performance artist Karen Finley is organizing two of them. One of the events she’s doing is a conversation between herself and Bruce Yamamoto. Bruce’s work, although different, utilizes a similar tableau approach. Karen is also working with a group of graduate students here at NYU University who will consider particular aspects and artwork featured in this show to discuss. Andrew Lampert, senior curator at Anthology Film Archives, is curating a program of Mizer films that we are hosting at an NYU auditorium. He’s going to present film on film which is exciting, so it will be a unique opportunity to view the work in it’s original context and form. Vaginal Davis is hosting an event that will be structured like a talk show that includes diverse personalities such as critic-writer Vince Aletti, writer-historian Justin Spring, artist John Sonsini, and others to be announced. In addition, curator Pati Hertling will discuss archiving with a panel that includes gallerist Lia Gangitano, and artists Ulrike Müller, Nicola Tyson, and Martha Wilson.

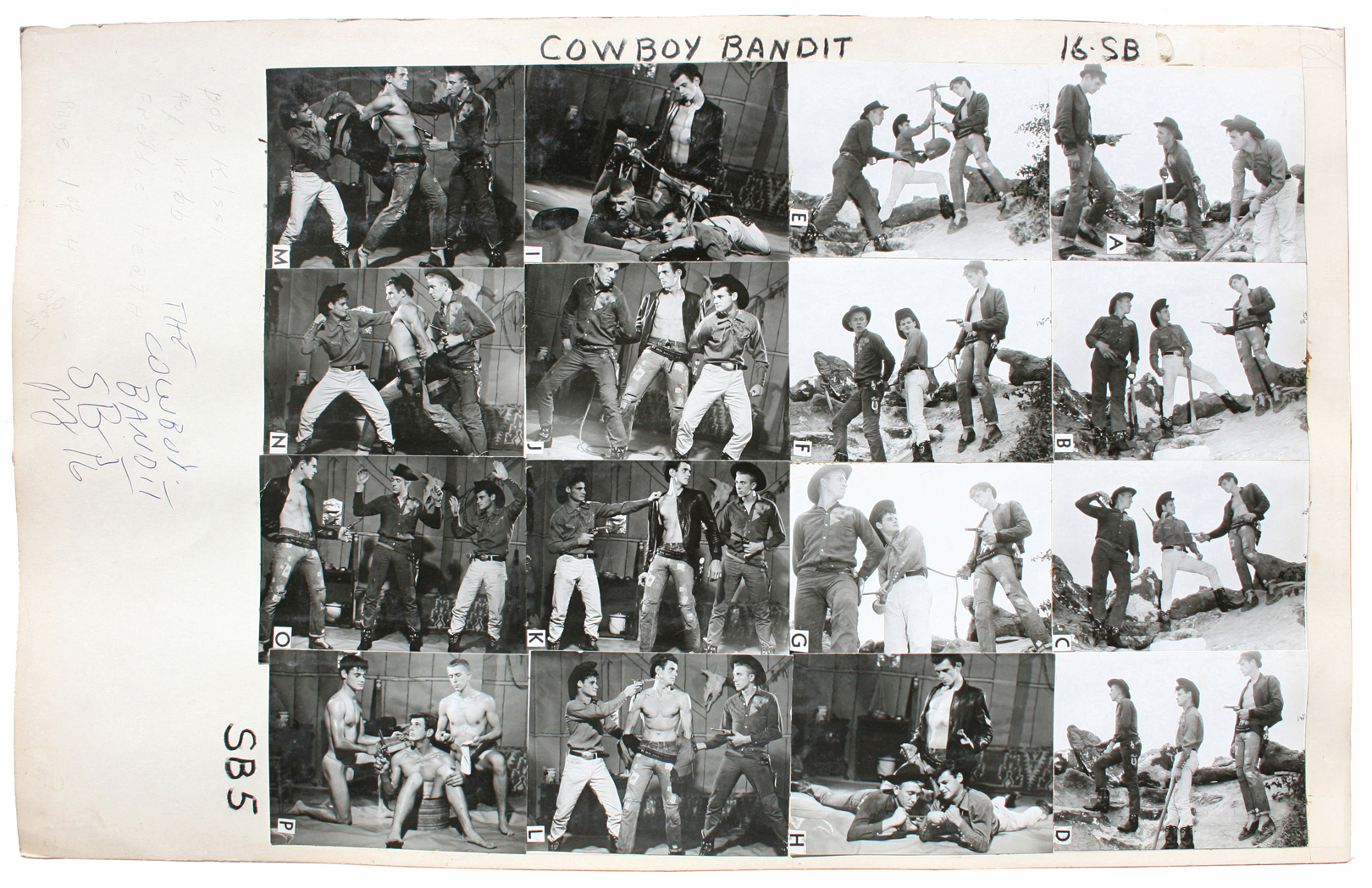

Bob Mizer: Cowboy Bandit (catalog board), 1960.

Bob Mizer: Cowboy Bandit (catalog board), 1960.

Bob Mizer: Unknown (jumping model), 1973.

Bob Mizer: Unknown (jumping model), 1973.

I don’t know if I misread this, but is there going to be a book after this exhibition?

JB: Yes, Brendan Dugan of Karma Books is going to design and publish a catalog in collaboration with the gallery and the Mizer Foundation. Actually, it will not really be a catalog but more of a book that in some way encompasses the nature of this project.

BM: It’s all part of the ongoing archaeological dig. The thing about Mizer is no matter where we go with this, if we keep looking we’re bound to uncover more aspects to bring to light. Just in the process of putting this show together we have all discovered new things. For instance, there’s a photograph of a guy with a Zorro mask on. I just thought it was a picture of a guy with a mask on but then Dennis Bell identified beyond a doubt that it’s of movie star Tyrone Power! Then the head of the costume department here (Tonya Blazio-Licorish) was able to tie the leather jacket in another photograph to the actual article of clothing in the collection: and she furthermore was able to point out specific things about the style and era of that piece. There’s such a wealth of material that the more you go into it the more you find, and then you’ll turn a corner and all of a sudden there will be this whole other thing you didn’t know was there. There’ s so much that’s yet to be discovered. The Foundation recently found 400,000 additional negatives!

DEVOTION: Excavating Bob Mizer is on view at 80 Washington Square East Gallery until February 15th, 2014.