PORTRAITS BY LINDSAY PERRYMAN | PAINTINGS BY ROBIN FRANCESCA WILLIAMS

ROBIN FRANCESCA WILLIAMS

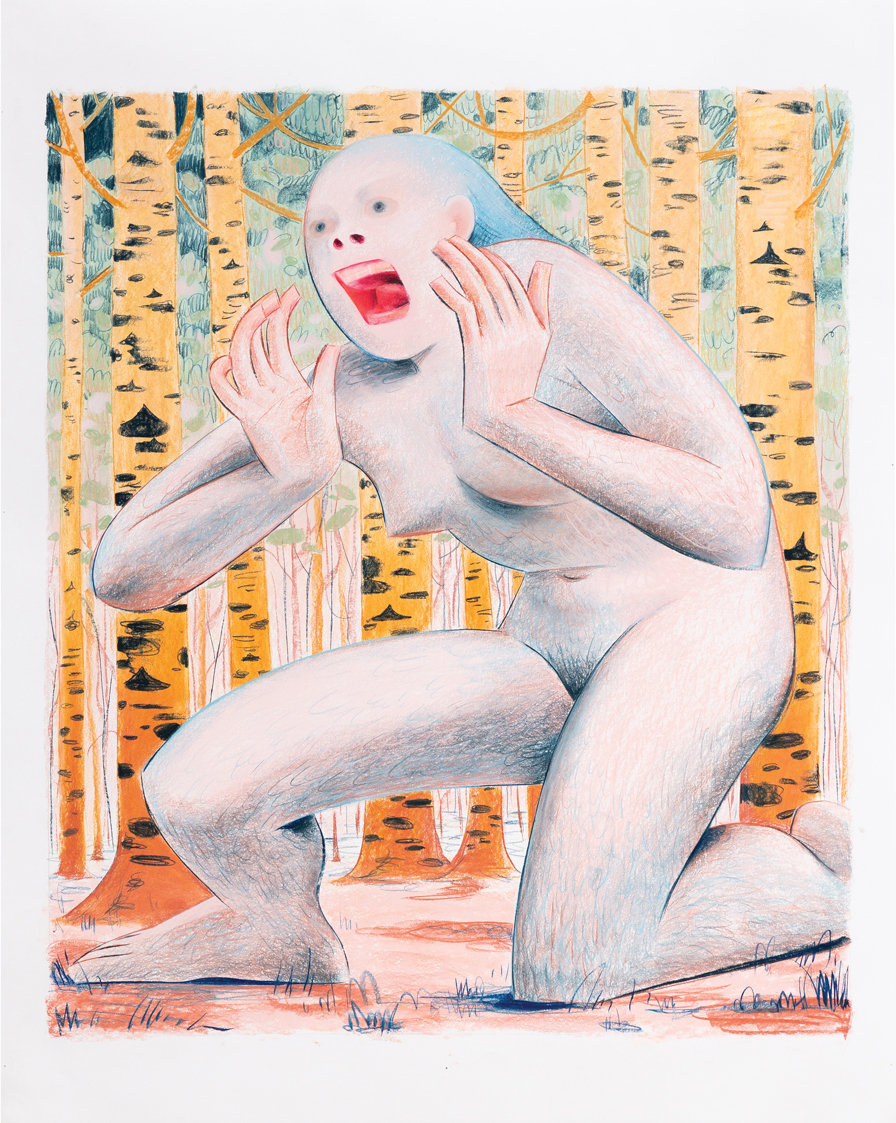

“I want it to feel as though these women are getting the last laugh,” artist Robin Francesca Williams explains about the toothy grins in her atmospheric portraits. With much of her work, Williams aims to show how women have been mistrusted, scapegoated, and demonized, but also to expose the expectation of their moral superiority, that they must kindly demonstrate purity and unconditional love on behalf of mankind. Interested in flawed, malicious, menacing, and wild female characters, she has a fascination with B-movies and cult classics, gravitating toward erotic thrillers because they tend to argue that the flaws of women are inherently more dangerous than the flaws of men. “They make tidy stories out of this belief,” she asserts. “My paintings are looking to untidy those stories and test these cultural contradictions.” She always renders her figures with a twist — a pregnant ghost, a kind troll hanging upside-down, or a dark angel as the embodiment of outer space. “None of my witches have pointy hats,” she laughs. “Sometimes I think about that test they did during the Salem witch trials — how they would throw a woman into the water. If she sank, then she wasn’t a witch, but she drowned. And if she floated and lived, then she was seen as a witch, and they would burn her. But I always thought if she was a real witch, she would constantly be a few steps ahead of them. She’d dive right in. She would just turn into water. Or turn into stone, sink to the bottom and walk out.”

With an exhibition of paintings at P.P.O.W. and a show of prints at Pace Prints planned for fall, Williams is poised to make a splash in New York, the city she’s called home since 2006. “It doesn’t feel real,” she confesses. She feels lucky to show and sell her art and remembers a time when she couldn’t get anyone to engage with her work. At the height of Zombie Formalism, when abstract paintings were all the rage after the last recession, she was just trying to get by — waiting tables, teaching, assisting scenic designers, renting out a room in her apartment, and occasionally getting a freelance illustration project. “It’s not a time in my life that I romanticize,” she recalls “No individual should have to take on that many jobs just to make ends meet. The gig economy does not feel like an artistic proving ground.” She credits an all-female crit group in New York for giving her a sense of community, helping her understand herself more, and creating context for her work. Being a figurative painter often means contending with whitewashed and male-dominated art history, a legacy of painting co-opting the female experience. Because she did not want to contribute to the objectification of bodies, she did not paint women for years. “It is still not an easy task,” she admits. “I want them to be sexual but not consumable.”

“Ghost at War” (2020).

“Ghost at War” (2020).

“Ghost in Labor” (2020).

“Ghost in Labor” (2020).

“Out Witch” (2020).

“Out Witch” (2020).

“Witch Babies (study)” (2020).

“Witch Babies (study)” (2020).

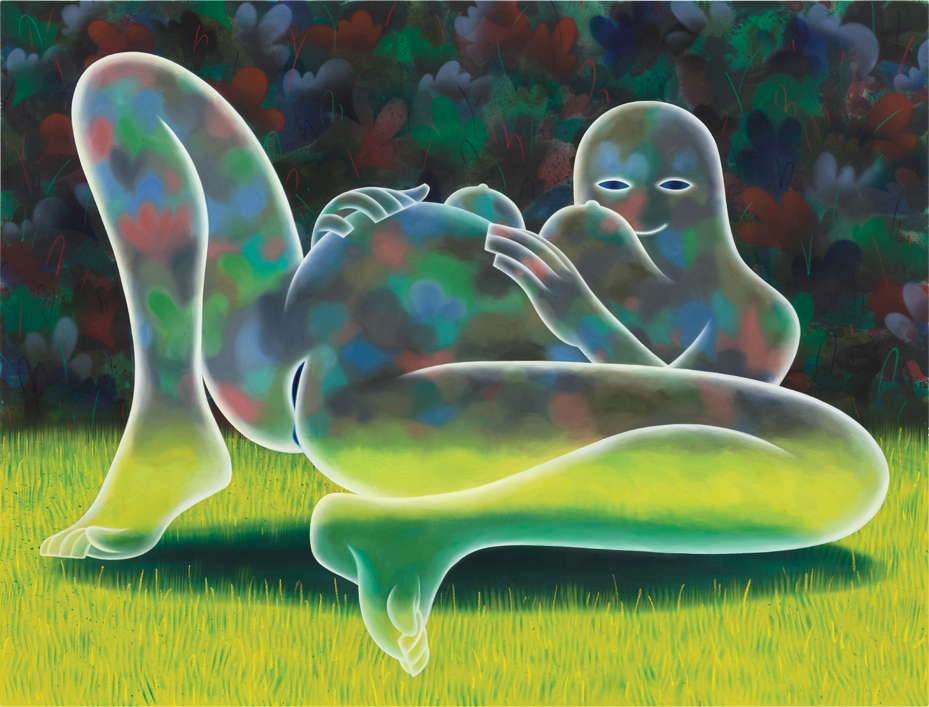

“Eco Dom” (2021).

“Eco Dom” (2021).

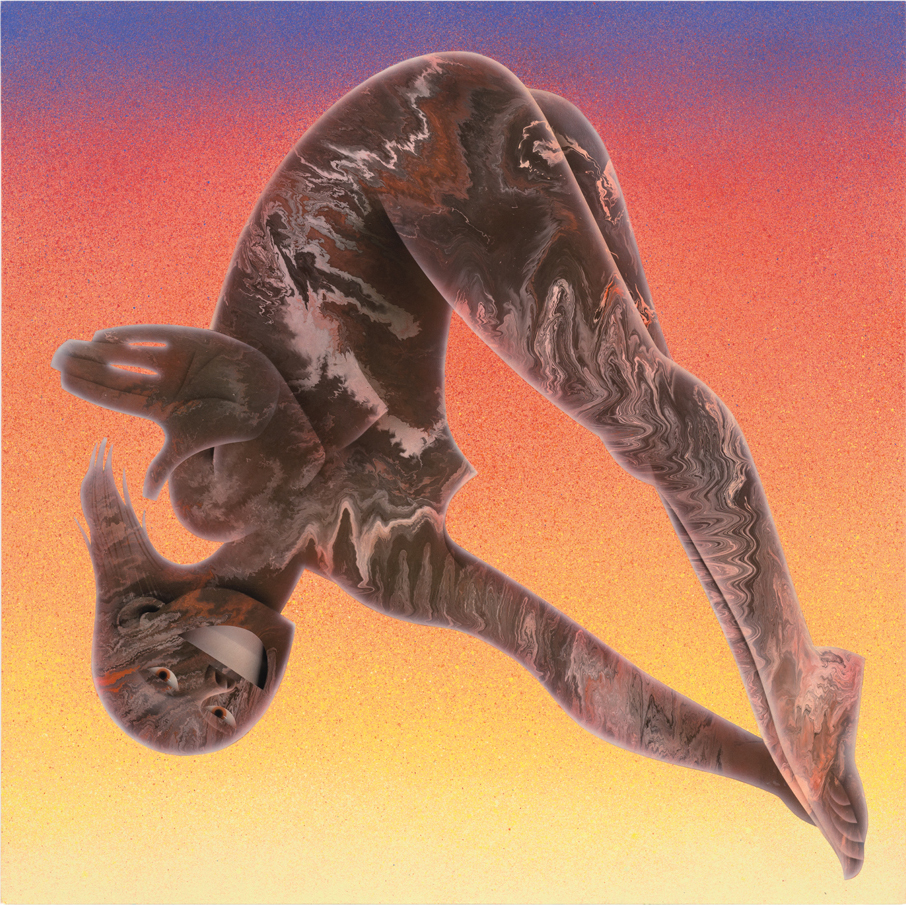

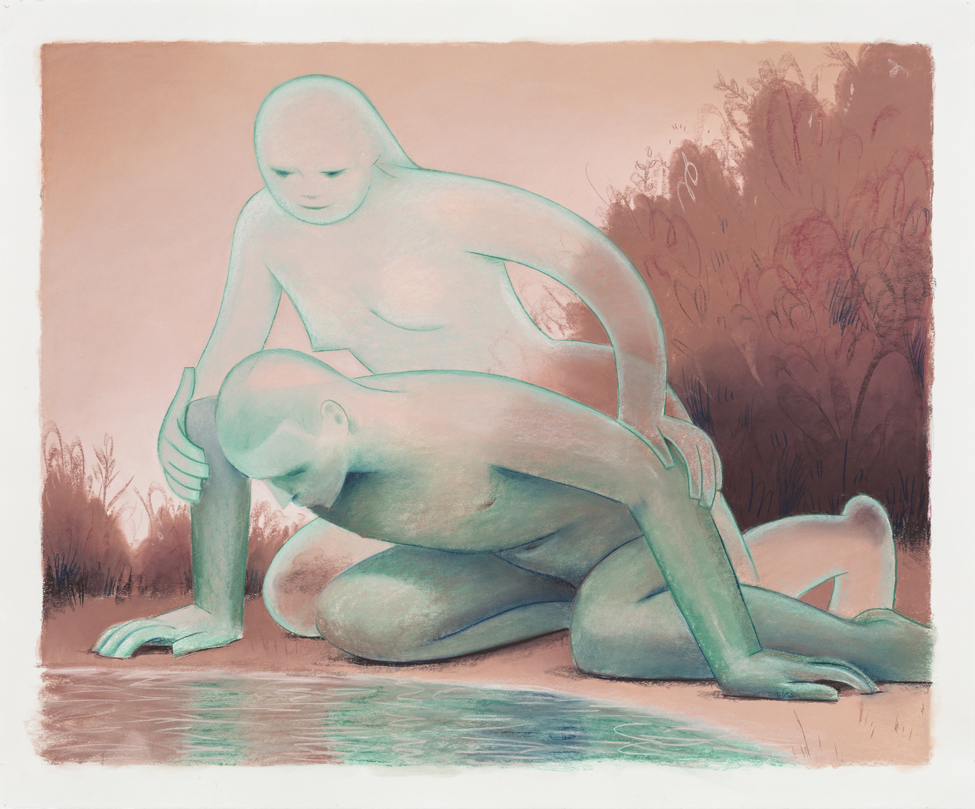

Some of Williams’s subjects are deliberately genderless, cleverly pared down to the smooth approximation of a smiling face, their gestural boundaries made using a combination of lines and layering. The artist’s signature style was developed formally by experimenting with tape, masking off areas with thin lines and filling in these areas with the desired contrast or texture. “Curiosity and play are important to me,” Williams insists. “Art school was very formative, but it was only the beginning of my education.” Brushing, scraping, pouring, marbling, splattering, airbrushing — her painting process is brimming with technique. She uses an assortment of materials to achieve specific colors and finishes, including Flashe vinyl paint which gives a matte effect often used for industrial signage. Her references span “faux” painting techniques traditionally used by set designers as well as methods she adapts from Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok videos. If it all sounds complicated, it can be. Williams even keeps a whiteboard in her studio to keep track of the applications for each type of paint. But the result of all these material explorations is worth it, resulting in a shallow sculptural relief on the surface of her paintings that is best seen in person.

This layered approach extends to Williams’s compositions too, which subvert the conventional figure-ground relationship. Sometimes the silhouettes of bodies become portals or windows to another space; other times her figures are semi-transparent like specters, appearing as part of the air, or part of the painting’s negative space. She creates a depth of scenery in her compositions by staging flat layers of a reality that seem to peel away or punch through to expose another dimension. “Their bodies are windows into systems,” Williams elaborates, “They are unsolid and can’t be understood or blamed, but instead reveal something bigger than themselves.” A degree of abstraction keeps the viewer in a constant state of renegotiation with the immediacy of her figures; though her titles are a quiet directive, she does not handfeed narratives. The work instead offers a transcendental reminder that time and space are relative. “America is just one big haunted casino,” Williams quips. But even under such grim circumstances, her works might remind us we are metaphysical hosts, playgrounds for trillions of bacteria and microorganisms, and that furthermore, everything is made of stardust.

“A Sound Around No One 2 (study)” (2020).

“A Sound Around No One 2 (study)” (2020).

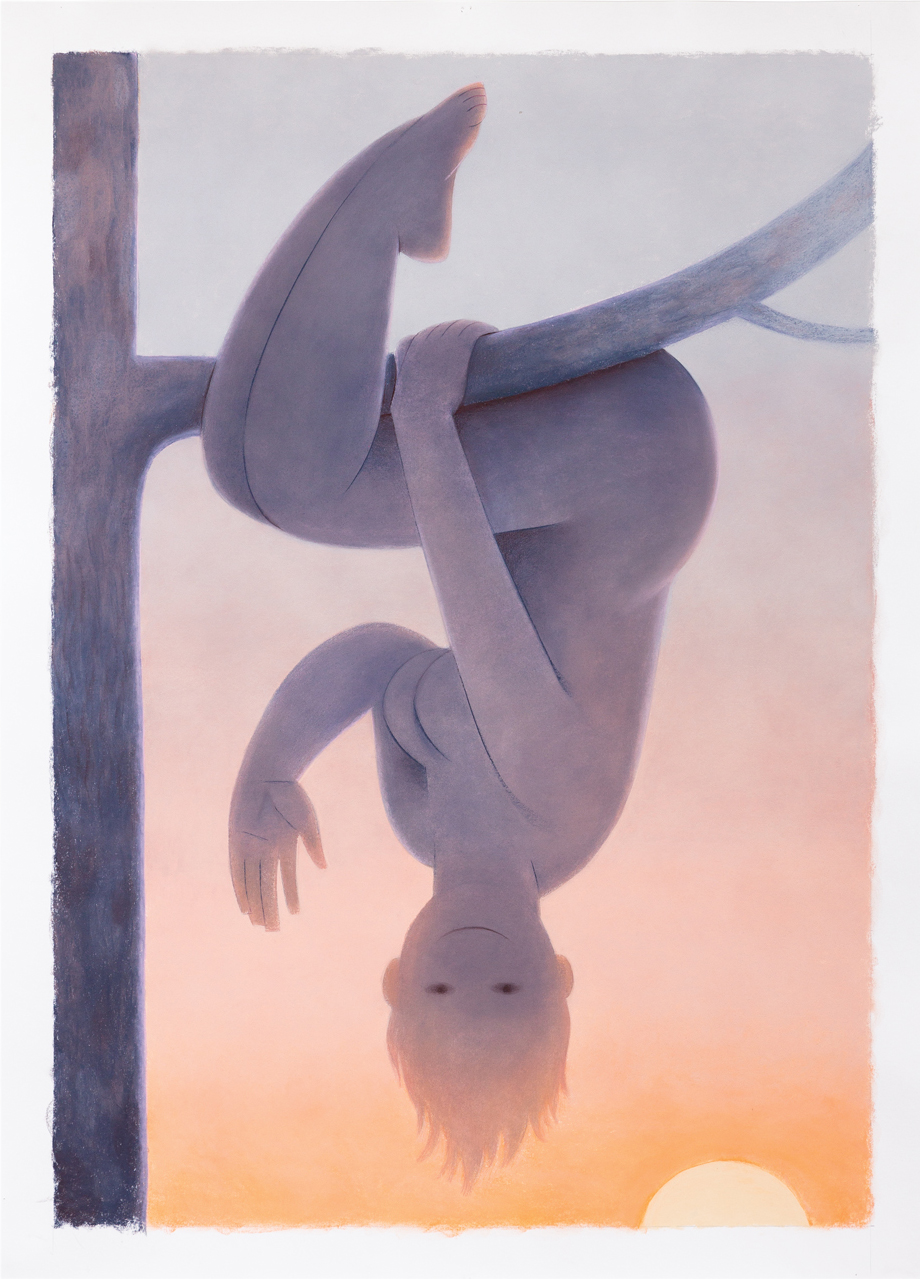

“Troll (study)” (2020).

“Troll (study)” (2020).

“Stalkers” (2020).

“Stalkers” (2020).

“Space Angel” (2020).

“Space Angel” (2020).

Robin Francesca Williams photographed by Lindsay Perryman at her studio in Brooklyn, New York. May 2021.

Robin Francesca Williams photographed by Lindsay Perryman at her studio in Brooklyn, New York. May 2021.

All artworks courtesy of Robin F. Williams and P·P·O·W, New York.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.