PORTRAITS BY RENEE COX

CARLOS MARTIEL

With his body at the center of his durational performances, Martiel pushes his own limits while also calling attention to deplorable histories.

Perhaps we should start at the beginning; could you speak a little bit about what it was like coming up in Cuba? When did you begin performing? I started working in performance in 2007. I remember that back in the day I was studying goldsmithing at the San Alejandro Art Academy, and alongside my jewelry work, I was also making unconventional drawings. I say unconventional because the materials I was using to make them were not traditional, like oil or acrylic paint, or even using a canvas. I was using different pigments, such as iron oxide diluted in vinegar, coal, beeswax, and blood. And it was the use of my own blood, specifically, which catapulted me to working with my own body. To extract my blood and make drawings, I had to go to public clinics and ask the nurses on duty to perform a phlebotomy on me. At first they agreed to do it, but as I started coming to the clinic more often, they began to either decrease the amount of blood extracted or refuse to do it altogether. This caused a great deal of frustration, since I couldn’t materialize the type of work I wished to make. That’s when I had the idea of using my body as an object and a subject of my conceptual interests, without having to depend on a third party. This is how I came to realize my first performance.

I am blown away at your roster of past performances; you are quite prolific. How do you develop your performances? Do you keep a journal? When I lived in Cuba, most of the time I did my performances in public spaces. Back then my work was not well-known, and institutions in Havana weren’t paying attention to me, which allowed me to freely explore various backdrops to my practice. I did performances on the coast, rivers, cemeteries, on the street, and sometimes even unannounced. The themes addressed in my work were immigration, racism, and the abuse of power by the Cuban government. Since 2012, when I left Cuba, my way of developing performances has changed. For example, since 2015 I’ve made most of my work through commissions, making me reach for a different level of rigor for each proposal I created. In general, when I receive an invitation to develop a work, I first conduct research on the context and the city in which the piece will take place, and I choose a problem that is linked to the themes that I have approached in previous works. Once I set my mind on a specific theme, I develop a conceptual idea and look for the way I can turn it into a concrete image. I really enjoy sketching and drawing my performance ideas on paper.

How do you document your work? Generally, with photos and video. I remember that in the beginning of my artistic career I had a professor, Humberto Díaz, and he always said to me, “You have to document everything you do, and the documentation needs to be of the highest possible quality,” since my work depends on documentation to be able to transcend time.

“South Body” (2019).

“South Body” (2019).

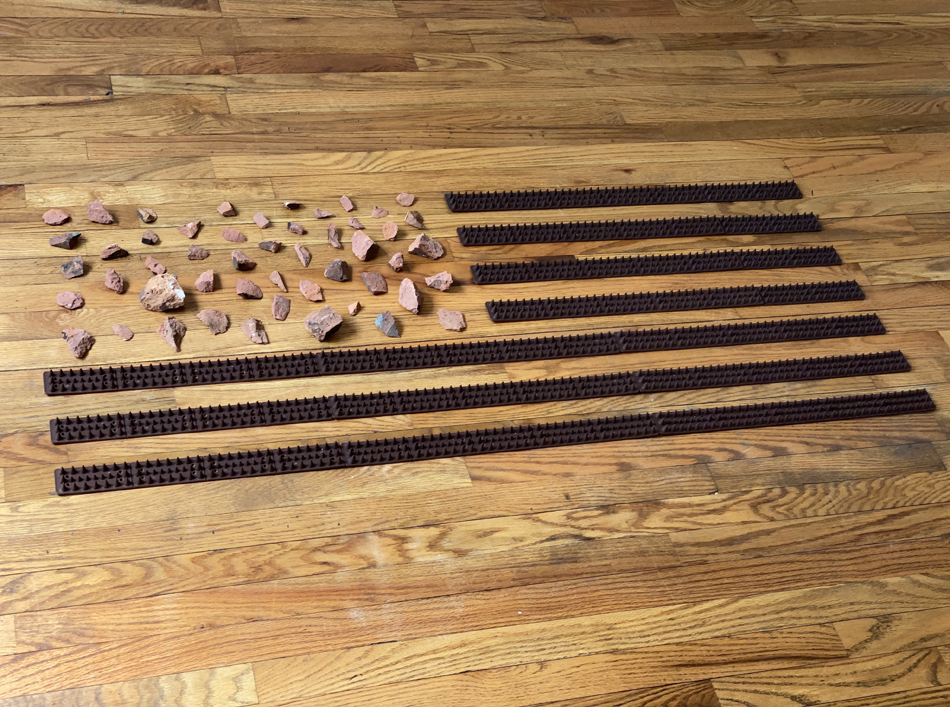

“Insignia II,” (2020). Photo: Justin McHugh.

“Insignia II,” (2020). Photo: Justin McHugh.

“Dictadura” (2015). Photo: Oriol Tarridas.

“Dictadura” (2015). Photo: Oriol Tarridas.

“Intruder (América)” (2018). Photo: Walter Wlodarczyk.

“Intruder (América)” (2018). Photo: Walter Wlodarczyk.

Are the physical elements of your performances then rendered as art artifacts to be displayed or collected after the performance? Have you ever done a show that did not involve performance? Various materials or objects that I’ve used during my performances have survived and remained as sculptural pieces after the performative gesture. What I mean by this is that in a number of solo exhibitions, some of these objects have been displayed. This is yet another way of documenting the works, and to me they are like relics, because every performance I do is unique and unrepeatable. In my most recent show at the Lux Art Institute (now ICA San Diego), titled The Shadow of the Color Line, I showed photographs, videos, but also objects, like the flag I used in the Cuerpo Sur (South Body) performance or the diamonds that I featured in Continente (Continent), to name a few examples.

Many of your performances revolve around your body. What is the experience of performing in a participatory environment? Have you ever had strange experiences with audience members? Most of the time, the audience’s participation in my performances is passive and oriented towards contemplation. In one work or another, I’ve invited the audience to participate more actively, like in Basamento (Basement) or Intersección (Intersection), but I just allow this when this intervention is conceptually important.

Of course, I’ve had unexpected experiences with the audience, or maybe not the general audience, but with specific individuals that have taken liberties and attributions that are out of line. I remember one occasion when I was presenting the Black Lament performance in the courtyard of the Roski School of Art and Design — University of Southern California. I was standing naked in a pool of my own blood and the evening was a bit chilly. Suddenly, a person walked up to me and whispered, “Are you cold? Do you want to borrow my jacket?” And he was about to take it off to put it on me. I stared at him directly and told him if he wanted to do social work, he should be doing it out in the street — a more adequate space than in a gallery.

How has your life and work changed during the pandemic? 2020, what a year… Covid-19. The arrival of the pandemic in my life has been hard and still is, though not as much lately — but it was harsh during most of last year. I was forced to make voluntary and involuntary changes, and changing is not an easy thing to do, as we all know. I had to reinvent myself as an artist as a way to survive, since I couldn’t travel for obvious reasons, and above all I needed to keep exercising my creativity. During the pandemic I developed a series of objects and installations in my studio, among them Insignia, El Rey Desnudo (The Naked King) or Fundamento (Basis). This last performance was made in my studio after the assassination of George Floyd. In this work, I remained still and lying down on the floor with a U.S. flag tying my hands and feet together. The work was conceived in the context of the Black Lives Matter movement and refers to the historic oppression and systematic violence that the BIPOC population is subjected to in the Americas, and more specifically in the United States.

Personally, I can say that in 2020 I needed to deal with some of my demons and from that pain, a number of positive outcomes and changes happened, which is why I’m thankful for the difficult situations that I had to experience. For example, I quit smoking and drinking alcohol, implemented a healthier lifestyle for myself, and went vegan.

Which performances were the most painful? What was your longest performance? The most painful work I’ve done has been Condecoración Martiel, Carlos (Award Martiel, Carlos), for which I underwent a surgery in which 2.3 inches of flesh were removed from my body. Afterwards, this piece of skin was dissected by an art conservator and inserted within the disk of a gold medal, similar to those awarded by the Cuban government to select citizens. The technical details of the work were tattooed around the scar on my body, leaving a permanent registry on my skin as a certificate of this decoration. The process of the work and my recovery lasted three months overall. After making performance works like this, something breaks in you. Award Martiel, Carlos was one of the harshest things I performed on myself and it made me question the purpose of my work as a whole.

The longest performances I’ve done were Dictadura (Dictatorship) and Mulo (Mule). In the first one, I was lying down with my neck attached to a flagpole on which were hoisted, for an hour’s time each, the flags of Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru, Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Suriname, Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Cuba. These countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have suffered (and in some cases, still do) from totalitarian regimes, most of which were actively supported by the School of the Americas, also known as Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation. In Mule, a work that reflects on the forms of modern-day slavery that particularly affect Latin American immigrants who work in the agro-food industry in the United States. I remained still for eight hours with my legs immobilized by the dead trunk of a pear tree.

“El Rey Desnudo” (2020).

“El Rey Desnudo” (2020).

“Monumento I” (2021). Photo: Walter Wlodarczyk.

“Monumento I” (2021). Photo: Walter Wlodarczyk.

“Black Lament” (2018). Photo: Hiroshi Clark.

“Black Lament” (2018). Photo: Hiroshi Clark.

“Peso muerto (Dead Weight)” (2017). Photo: Renato Mangolin.

“Peso muerto (Dead Weight)” (2017). Photo: Renato Mangolin.

Let’s discuss your relationship with artist Tania Bruguera, a legend in the performance scene. How did you meet? I met Tania in Havana as a student, and in 2008 and 2010, I participated in the Cátedra Arte de Conducta, which she started. The Cátedra was a unique experience for me because the exercise of the collective critiques practiced awoke the professional and committed artist within me. I have really good memories from that time, since the first works I did out of school were in exhibitions staged by the Cátedra, like Integración, as well as having the opportunity to travel outside of Cuba for the first time. I have much to thank Tania Bruguera for, because she saw the artist in me from the very beginning. She gave me a great piece of advice that I often apply to my practice: “The artist who needs inspiration must look at their surroundings and observe reality.”

Do any particular inspirations resonate with you? While your work is strong in message and as a formal exploration, I do wonder which artists have been on your mind over the years? Every artist has their references, formal or conceptual, and I am no exception. In the beginning of my career those were Gina Pane, Ana Mendieta, Marina Abramovic, and Tania Bruguera, and today my sources of inspiration come more from literature or music, by Frantz Fanon, Eduardo Galeano, or Mercedes Sosa. Inspiration in the form of profound queer friendship, intimacy, and critique, like Jose Esteban Muñoz suggests, is also important. So I am thankful and inspired by being amigxs with artists Camilo Godoy and Jorge Sánchez.

Peter Schjeldahl wrote in his New Yorker review of the 2019 Whitney Biennial, “If politics is about winning power through persuasion, much of the art at hand hardly qualifies as political.” Do you think your work is political in this sense? How might you define political art? Nowadays, it’s trendy to say that all art is political, which I think is manipulative, since concepts or statements enable art that is hardly political to be branded as such. Art that doesn’t express, refer to, allude to, reflect on, or propose a change in reality, and in the oppressive circumstances that specific bodies (generally racialized ones) experience daily, cannot be called political.

My art is absolutely political. I couldn’t think of doing anything else because I was born in Cuba in the 1990s, because I am Black, because I have immigrant Haitian and Jamaican ancestry, because I am currently an immigrant, because I am queer, and because my art is the way I have found to express myself on the socio-political issues that not only affect my life, but those of others as well.

How do you feel about art critics? To tell you the truth, I don’t usually think about them.

How do you feel about the art market? I think that it is absolutely necessary that artists are able to live off the commercialization of their works. It makes no sense to me that you study art for so many years and that you are not able to make a living out of it. In terms of compensation, this career often proves to be very frustrating. What can I tell you about the art market? Not all the money involved is ill-gotten, and not all the art sold is good.

Any thoughts you want to share about the future of your work? Currently, I am working on a new project that will take place in June at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. The title of this performance piece is Pink Death and it’s inspired by the experience of one of my closest artist friends, Jorge Sánchez, who has been living with HIV since 2018. The work addresses the vulnerabilities of BIPOCs in HIV/AIDS narratives in the context of the Caribbean and the United States where structural stigmatization, racism, poverty, and lack of access to adequate health systems continue to weigh on this issue.

Carlos Martiel photographed by Renee Cox in the Hamptons, New York. June, 2021. Swimwear by Rufskin.

Carlos Martiel photographed by Renee Cox in the Hamptons, New York. June, 2021. Swimwear by Rufskin.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.