ERIC RHEIN

In his new book, the southern writer and artist channels the unknown and documents the intergenerational experience of HIV.

TEXT BY LOGAN LOCKNER

PORTRAITS BY BENJAMIN FREDRICKSON | ARTWORKS BY ERIC RHEIN

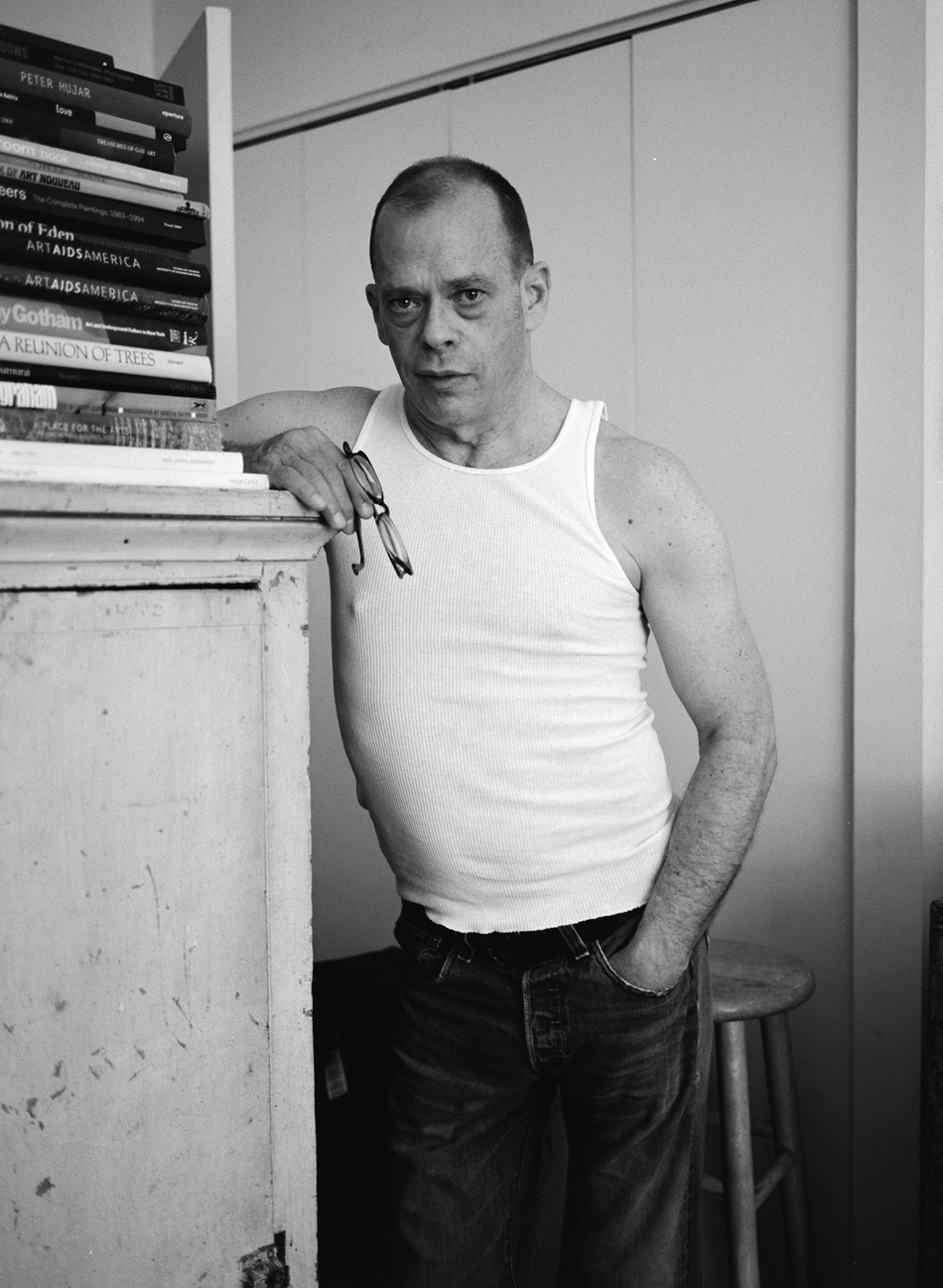

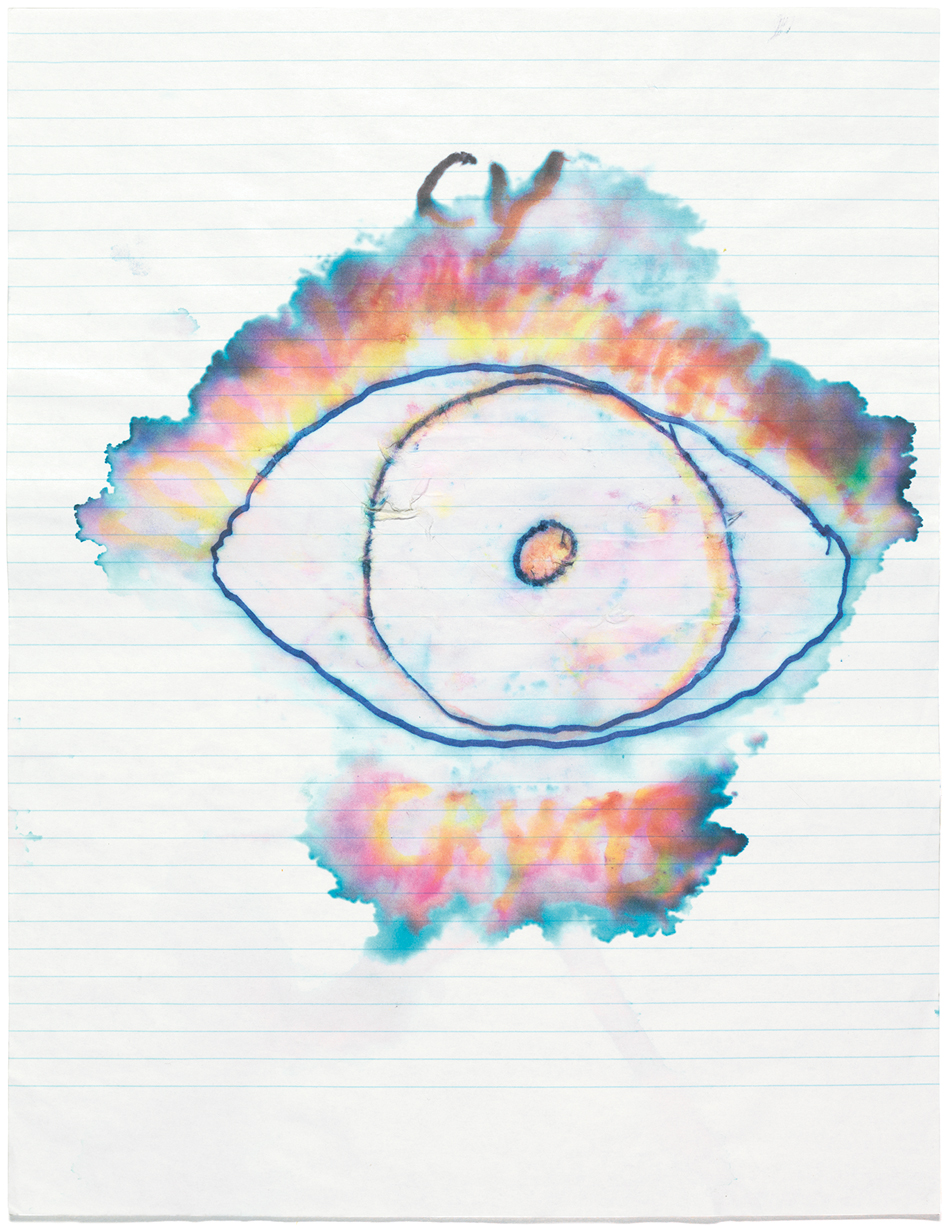

Eric Rhein posing in his apartment for Benjamin Fredrickson, New York City. March 2021.

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

Eric Rhein posing in his apartment for Benjamin Fredrickson, New York City. March 2021.

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

Eric Rhein posing in his apartment for Benjamin Fredrickson, New York City. March 2021.

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

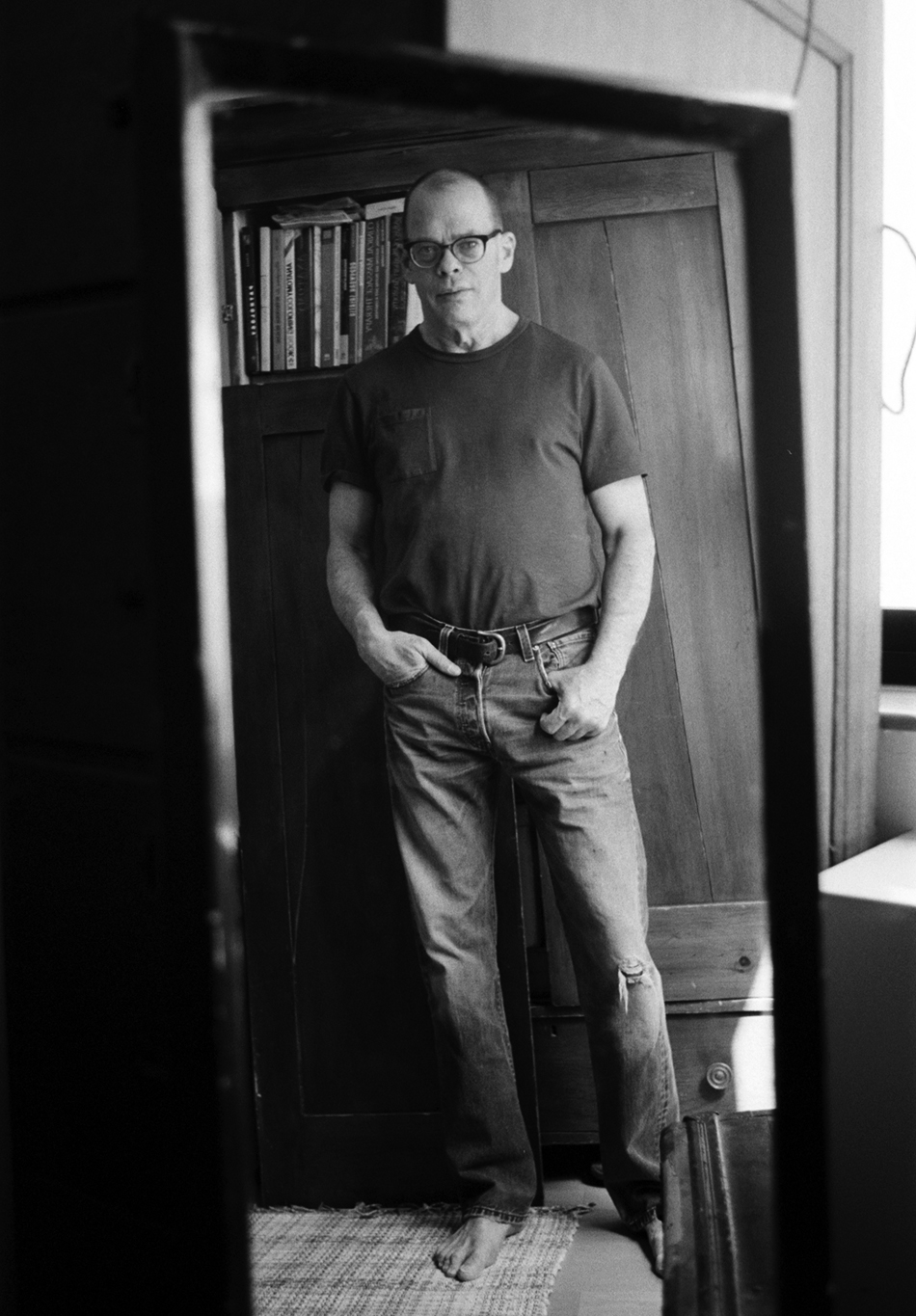

“Seated (self-portrait)” (1992).

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

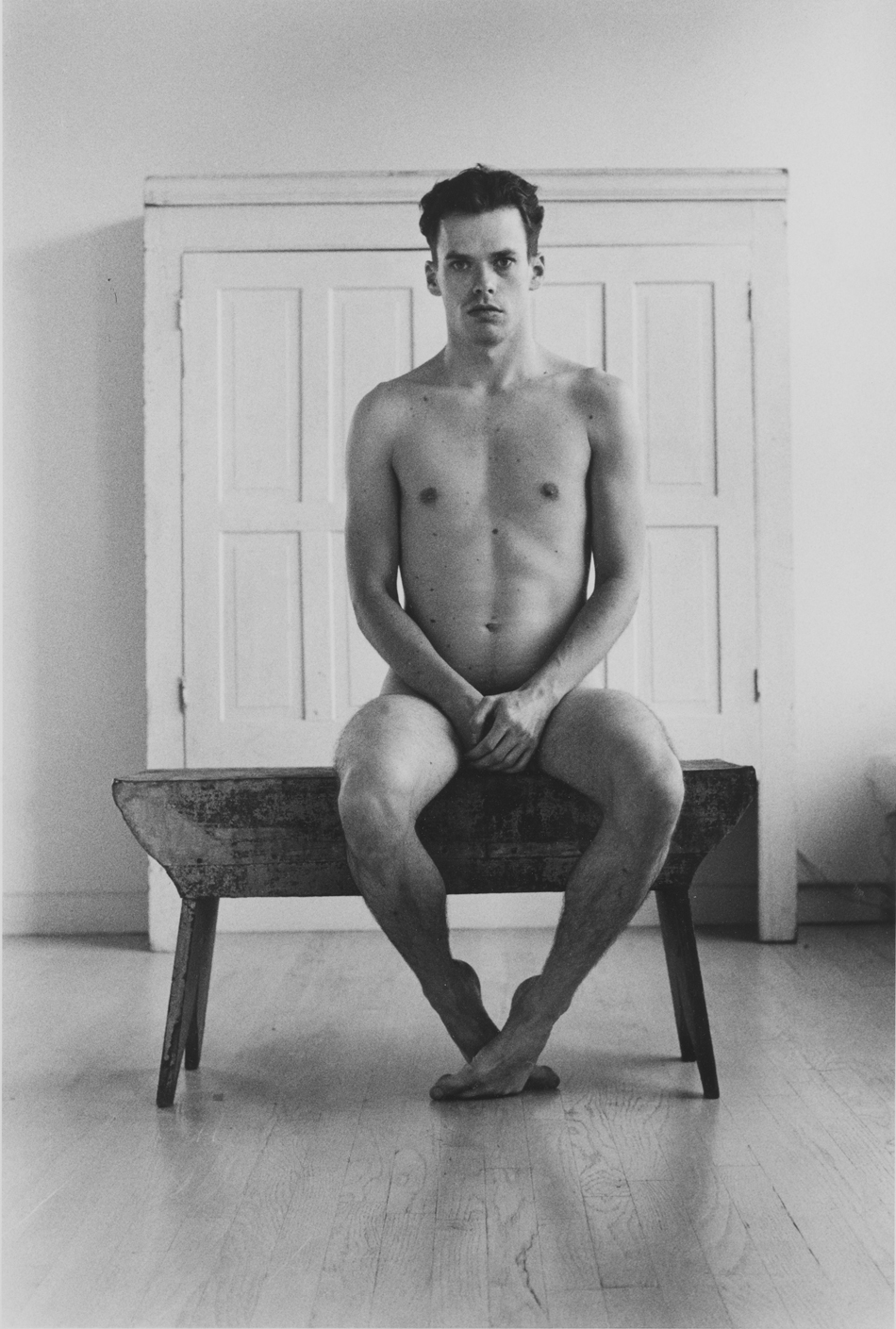

“Companions” (2019).

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

“Cy Tears” (1994) from “Hospital Drawings,” Saint Vincent’s Hospital.

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

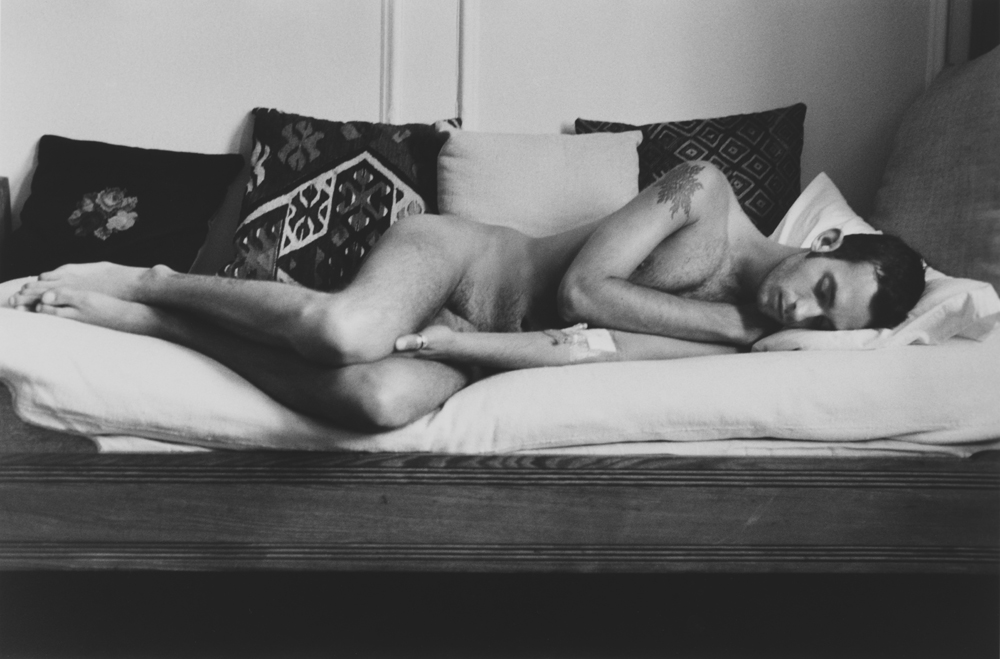

“Ken — Sleep (Ken Davis)” (1996).

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

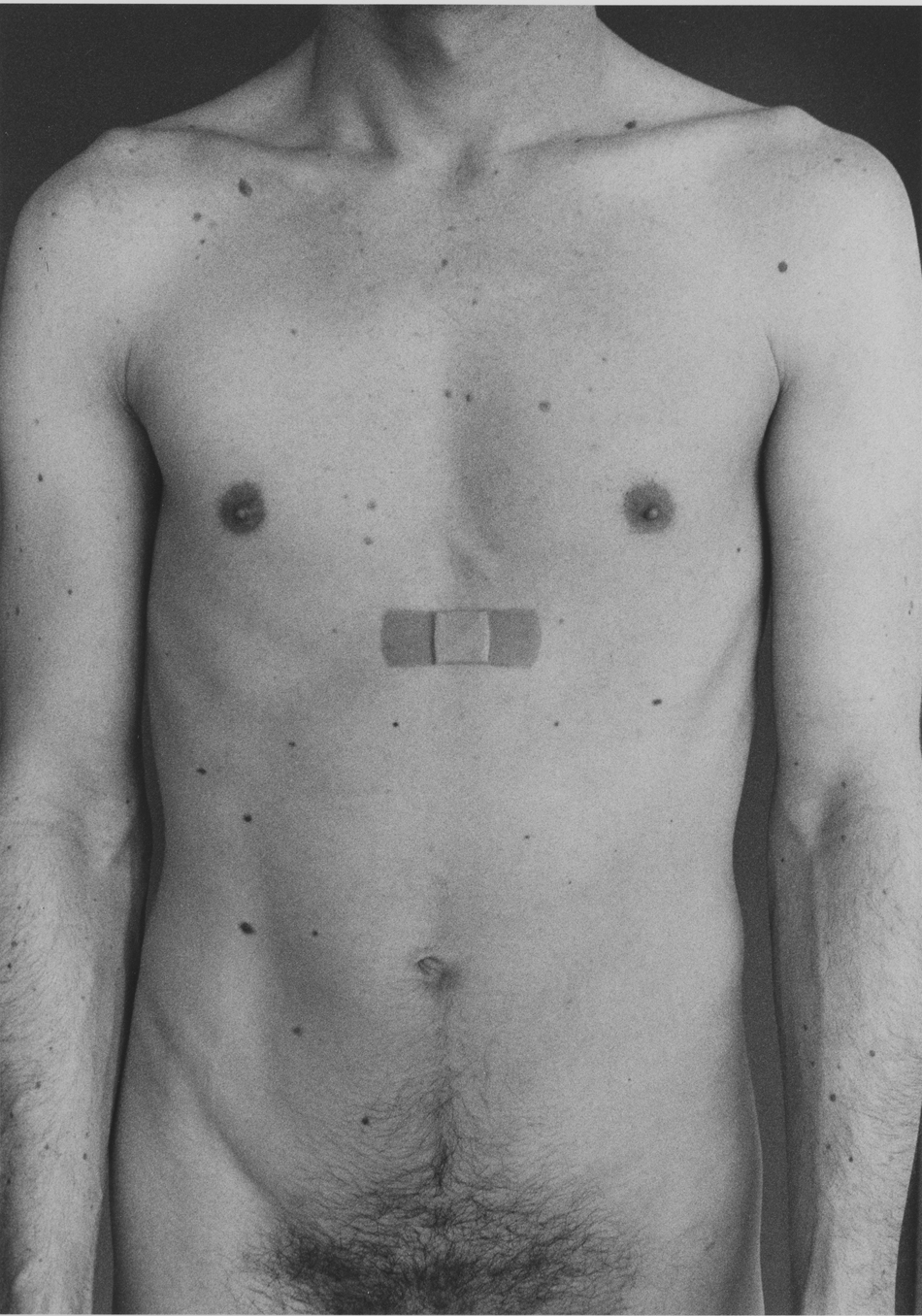

“Band-Aid (self-portrait)” (1993).

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

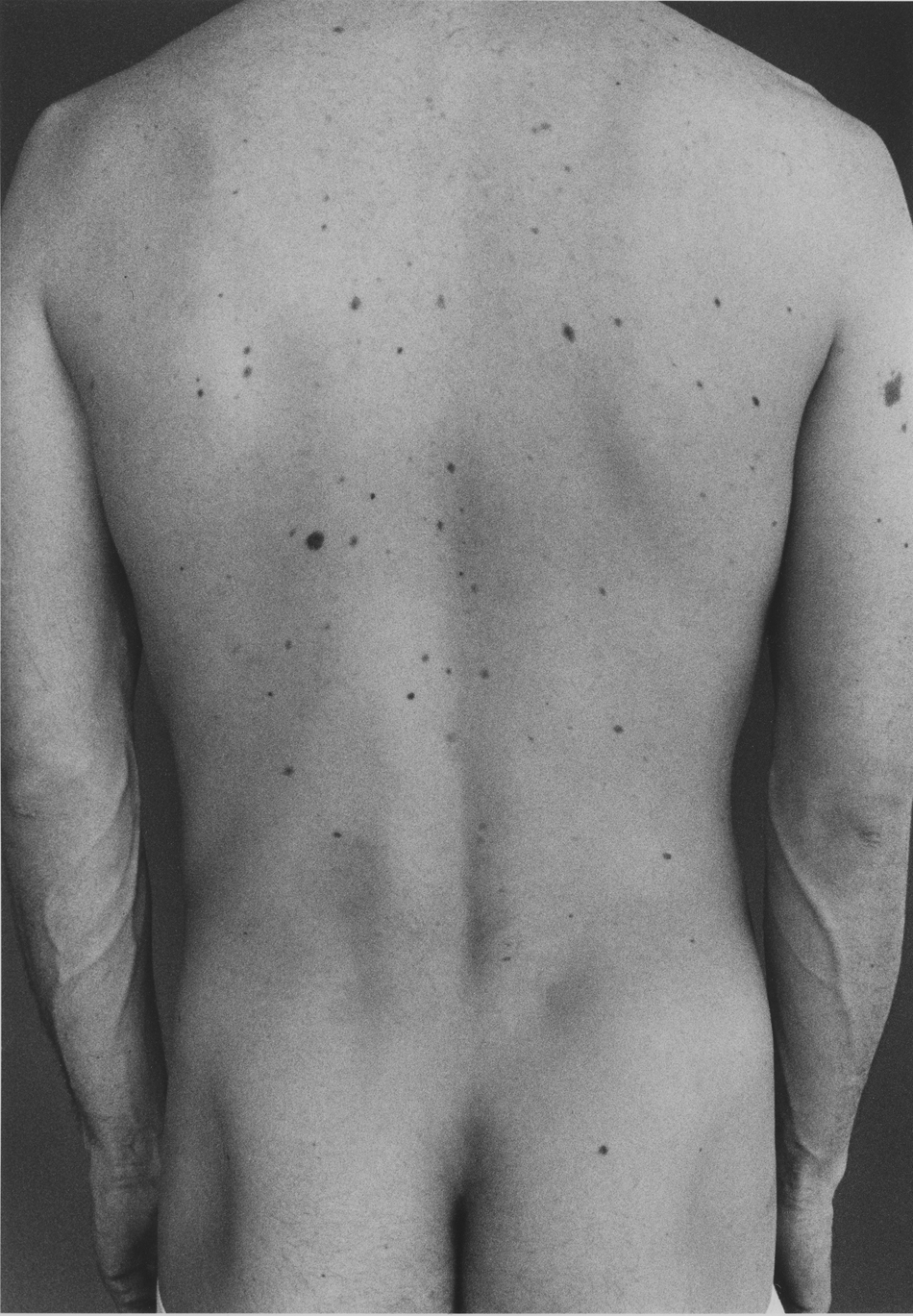

“Constellations (self-portrait)” (1993).

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

“Veil 2 (self-portrait with Russell Sharon, Hudson Valley)” (1994).

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

“River (self-portrait with Russell Sharon, Delaware Water Gap)” (1994).

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

“Silver Buck (Fire Island)” (2010).

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

“Jeff and Tim (Jeffrey Geiger and Tim Goetz)” (2005).

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

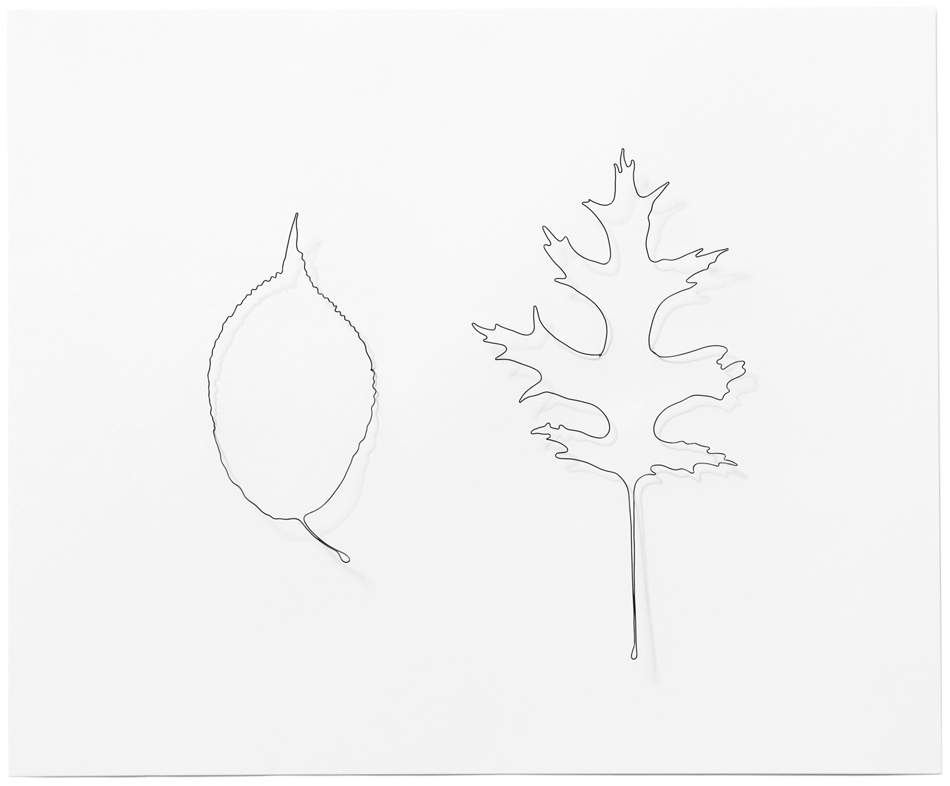

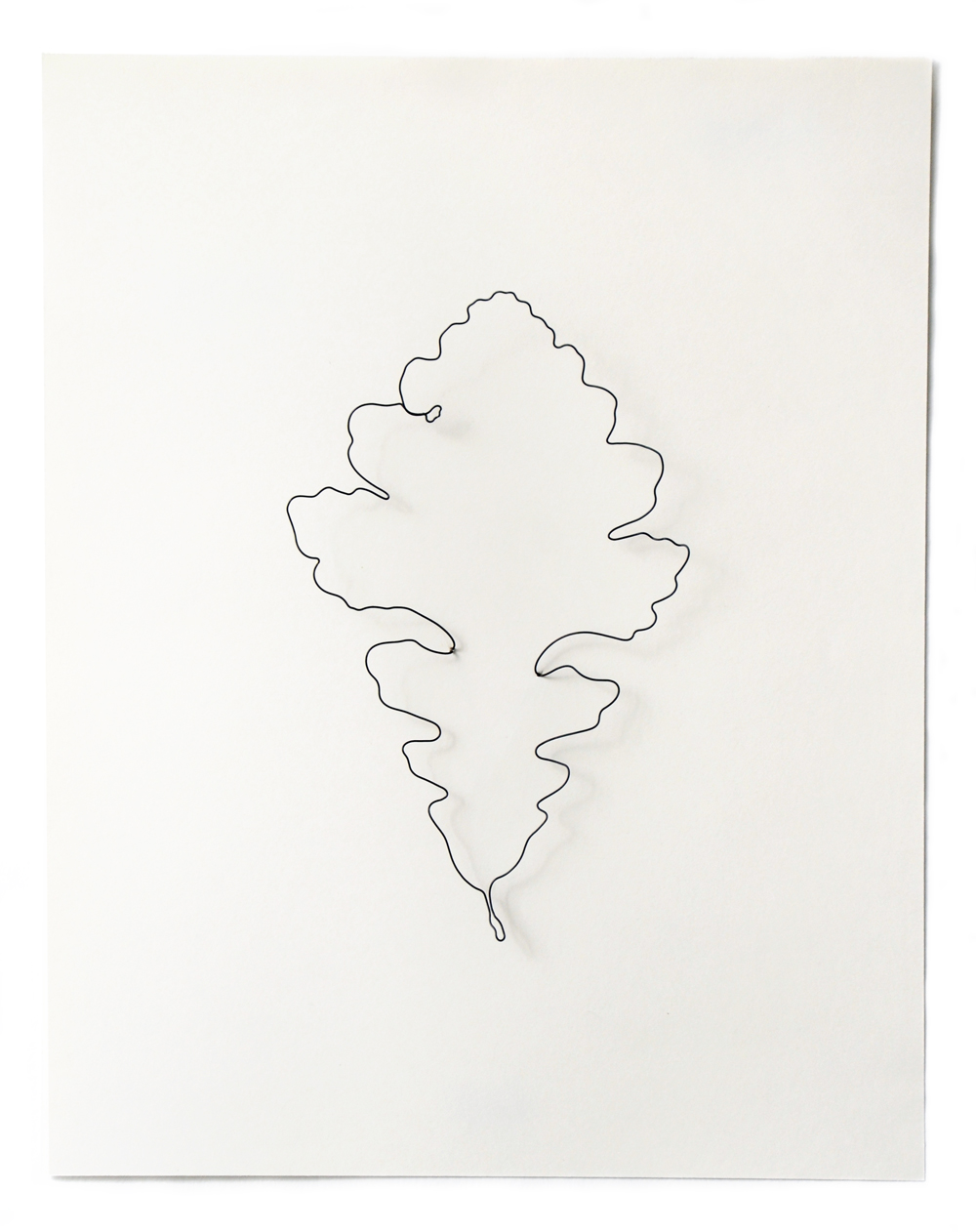

“Legendary Mark (Mark Morrisroe, 1959–1989)” (2018), from “Leaves (an AIDS memorial)”.

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

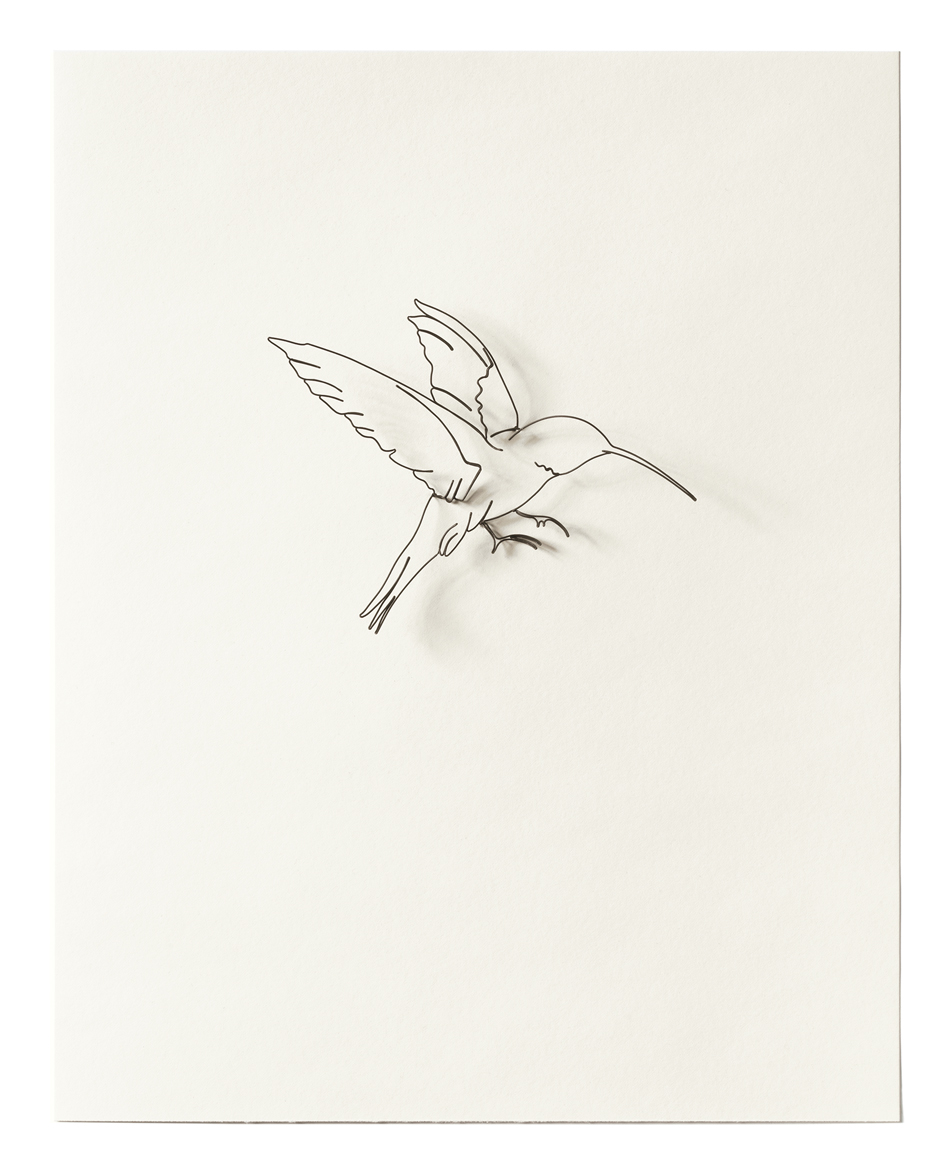

“Hummingbird 33–Flying East” (2018).

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

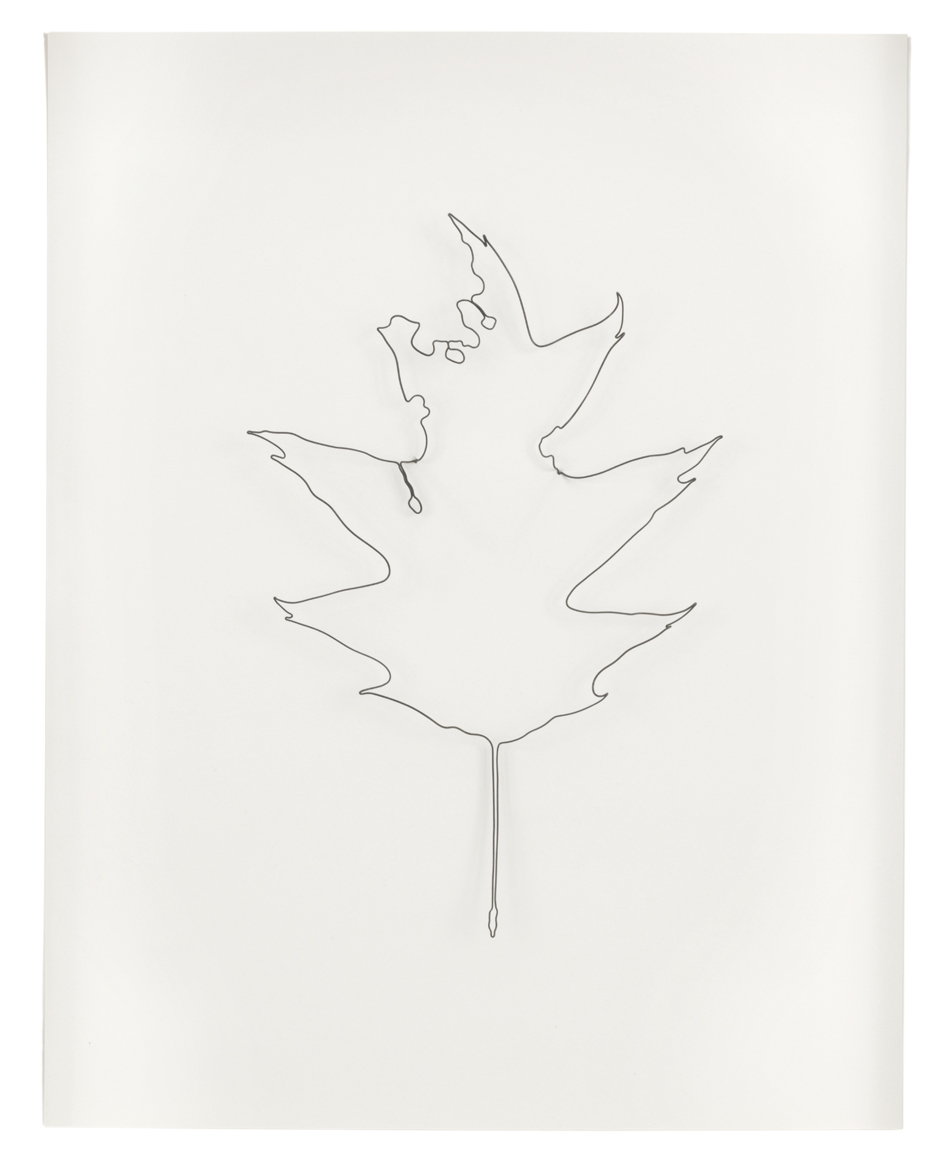

“Frank the Visionkeeper (Frank Moore, 1956–2002)” (2013), from “Leaves (an AIDS memorial).”

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

“Daydreaming (William Seymour and Richard)” (1991).

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

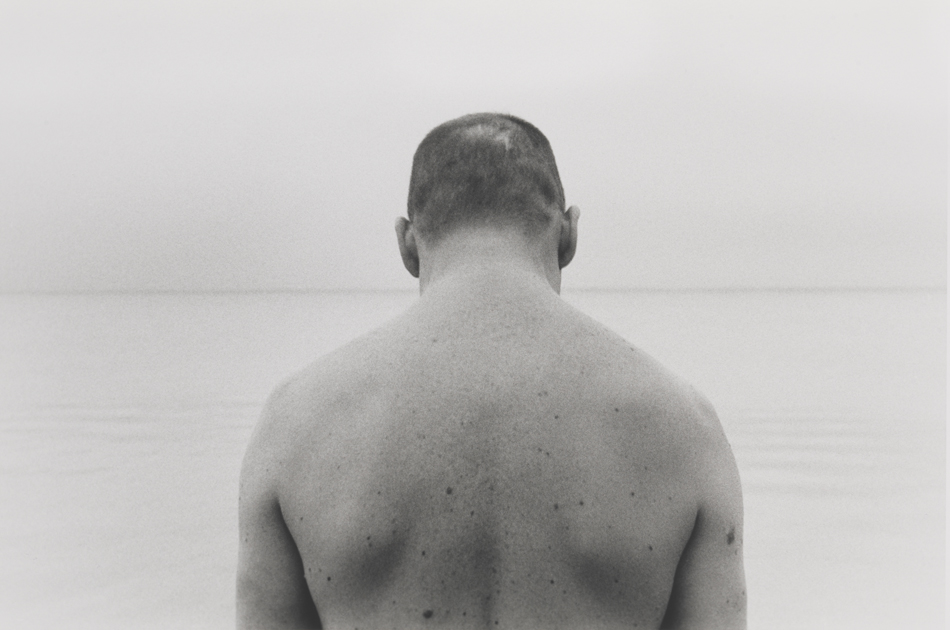

“Bay (self-portrait, Fire Island)” (2010).

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

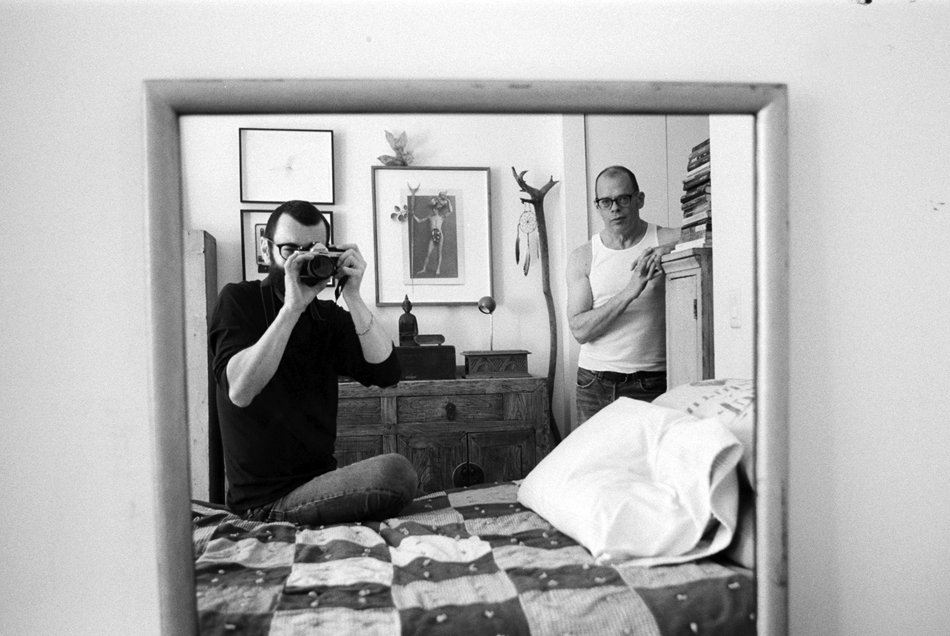

Eric Rhein in his bedroom with Benjamin Fredrickson, New York City. March 2021.

“It’s not unusual for me to have younger men visit my studio,” the artist Eric Rhein told me while we spoke over the phone in late March. One such visit occurred in August 2017, when Paul Michael Brown, a writer and curator who then served as director of Lexington, Kentucky-based Institute 193, came to Rhein’s studio in New York for the first time. The two had met a few weeks prior when Rhein, his mother, and his sister were in Kentucky — where his mother Shelbi had been born and raised — to participate in an oral history project focused on Lige Clarke, Shelbi’s brother. “Uncle Lige,” as Rhein calls him, was an early and outspoken advocate within the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. Clarke and his partner Jack Nichols wrote a column called “The Homosexual Citizen” for the groundbreaking gay publication The Mattachine Review beginning sometime around 1965, as well as two books on same-sex relationships: I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody (1972) and Roommates Can’t Always Be Lovers (1974).

During the studio visit, Rhein said, “Paul particularly gravitated toward this portfolio of photographs from the early 1990s: nude self-portraits, images of friends and lovers.” Rhein began making many of these photographs following his HIV diagnosis in 1987, and they offer glimpses of desire, intimacy, and care between him and his companions. A selection of these photographs — alongside images of Rhein’s assemblages of wire, leaves, pages of books, and other elements — was collected in the monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines, published by Institute 193 last fall. “The relevance and significance I saw in [the photographs] increased in recognition in more recent years,” Rhein told me. “It particularly struck me when Truvada came on the scene. Seeing these younger men with whom I was sharing this portfolio of what had become historical works — there was a mirroring between myself and these younger men in their mid-twenties to early thirties, the same age I was in the photographs that I was showing them, and in the conversations that would arise between us.”

Much like his artwork, Rhein’s manner of speaking finely balances delicacy and forcefulness. At multiple points in our conversation, I wondered if our connection had been lost, only to realize Rhein had paused mid-sentence to consider precisely what he wanted to say next. Once he articulates something, however, his sincerity is impossible to doubt. Speaking of his ongoing memorial project honoring lost friends and lovers, exquisite wire drawings of leaves and flowers, Rhein said: “Starting the Leaves piece was my response to genuinely feeling the spirits of people I knew who had died as this energy field that was enveloping me, holding me up to find my place in a world that I had been ready to leave. It wasn’t an intellectual decision to make something as a tribute to my friends who had died; it was a spiritual one.”

Even as black-and-white photographs, the images in Lifelines impart this profound sense of spiritual interconnectedness that is central to Rhein’s artwork and worldview. For him, this monograph is an important container of the intersecting experiences that tie together generations of gay and queer men. “Between Paul and me, there’s this intergenerational conversation: how does this younger HIV-negative man from the South and his upbringing and his consciousness of this time fit with mine, or my Uncle Lige’s, or yours?” he asked. “It’s a history we’re all involved with, and my photographs are the point of departure.” In the book’s introductory essay, Brown recounts discovering, during that first studio visit when they met, he was around the same age as Rhein was when he received his HIV diagnosis. “It feels important and serendipitous, and for a moment we live through the experience of the other,” he writes. “In moments like this, I feel like we’re family.”

Eric Rhein: Lifelines published by Institute 193 is available via this link.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 14, get a copy here.

1/19