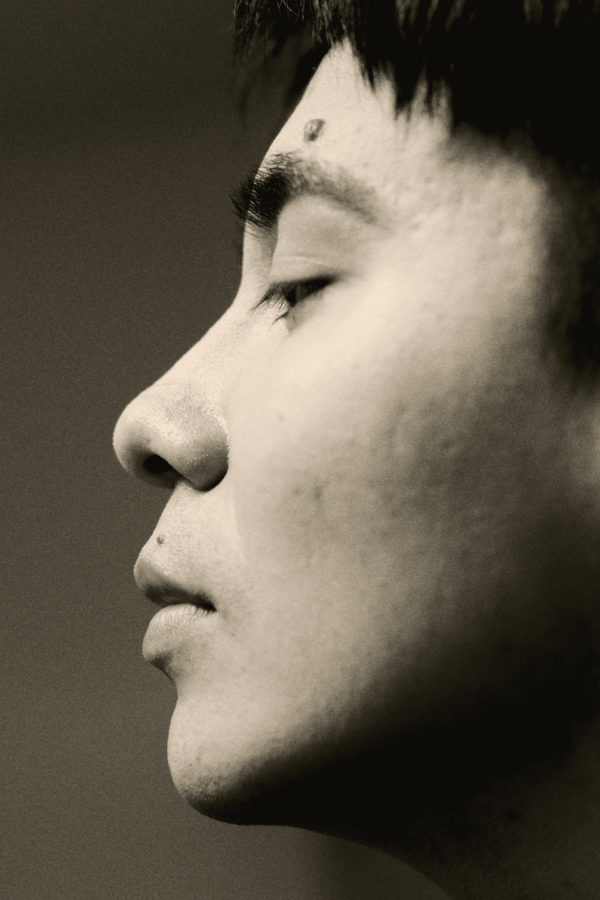

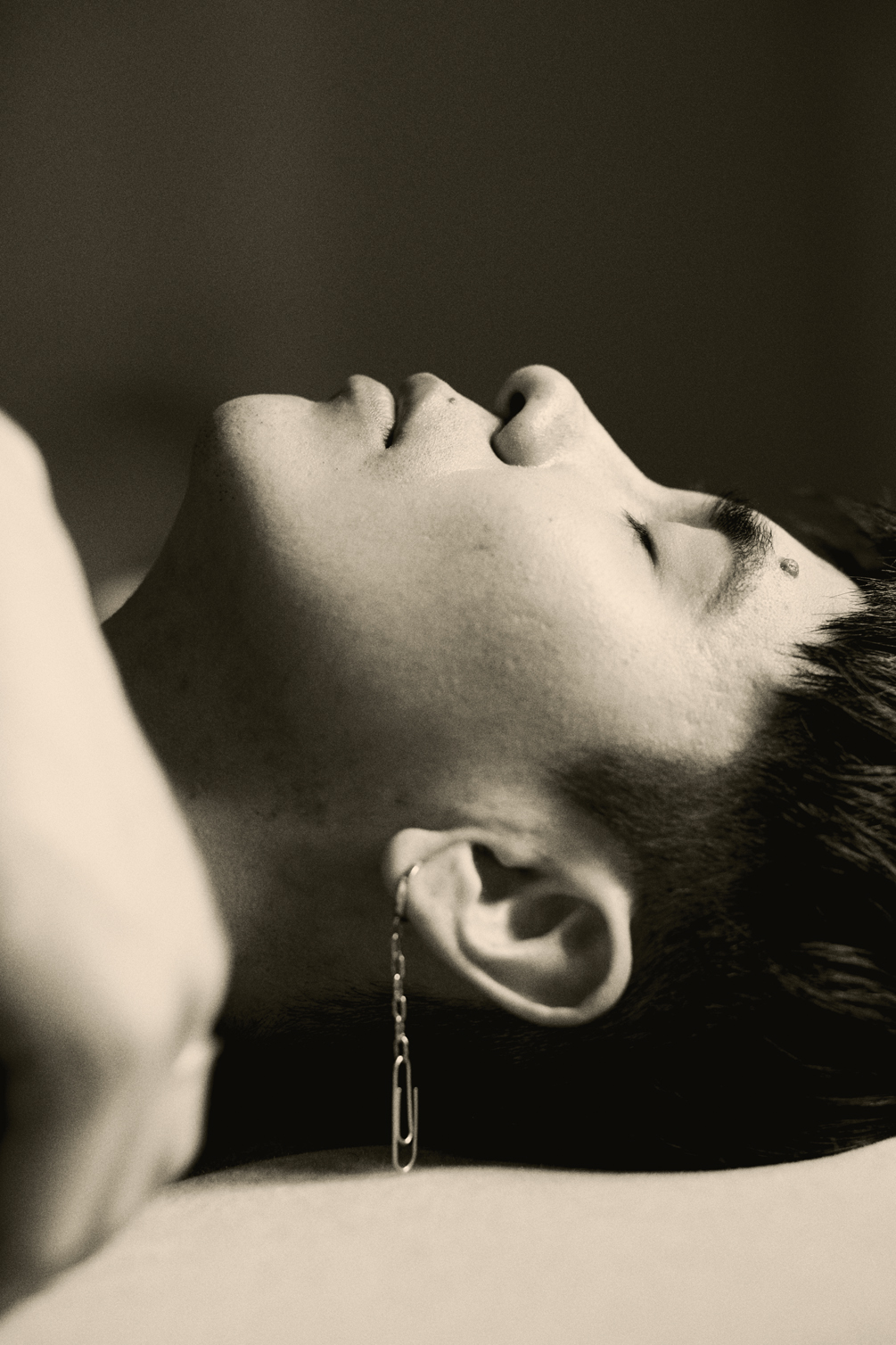

PHOTOGRAPHY BY FUJIO EMURA | STYLING BY SHO TATSUISHI

Ocean Vuong

It is impossible to ignore Ocean Vuong’s accolades: He’s won a MacArthur Genius Grant, a Whiting Award, the T.S. Eliot Prize for Poetry, and in 2019 his novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous was long-listed for the National Book Award while spending several weeks on the New York Times Best Seller list. His lyrical name is recognized outside of the literary circuit. Only so many authors are; many of them dead. That is to say, Ocean is not in the company of many contemporaries. While the ‘public intellectual’ has been called an endangered species, Ocean is one of the few we have writing today. This is more surprising given his lack of a Twitter presence, where writers often gain popularity for pontificating on anything and everything. Still Ocean, earning continued praise for his deft craftsmanship, is rarely far from the literary conversation. He is a writer’s writer — most comfortable at his desk, mulling over the pliability and banality of language.

Ocean broke out in 2016 with his debut collection of poetry Night Sky With Exit Wounds (Copper Canyon Press).. He enjoyed critical success and more. Fashion magazines, fashion brands, and even Netflix came knocking. Ocean, his star-ascendant, has made, and is making, poetry cool again.

Time Is A Mother, Ocean’s second collection of poems, arrives at a very different moment. While she lived long enough to see her son’s phenomenal success, in November 2019, Ocean’s mother passed away. She figures prominently in his first books as the central pillar of his matriarchal, immigrant family. The poems in Time Is A Mother turn away from Ocean’s previous style. Clear narratives expand into more associative timelines while representational imagery gives way to impressionistic scenes. Generally, the speaker of the poems is much less defined than in Ocean’s previous work. In Night Sky and On Earth, Ocean succeeded in making himself legible — as a poet, as a gay man, as an Asian-American. Time Is A Mother enjoys similar moments of legible identities, but the collection is most exciting as it deviates from preconceived ideas of Ocean’s poetry; that it is beautiful, and not too complex. Ocean’s new work puts forward a more experimental point of view. The speaker drifts into the banal, where poetry finds reality, rather than searching for realities that can become poetry. The book signals a great shift in the poet’s thinking.

Time Is A Mother feels very different — contextually, sonically, and formally — from your debut collection, Night Sky With Exit Wounds. What is your formal relationship to these new poems? I’m proud of everything I’ve done. That doesn’t mean there are not regrets. If I had a shot at editing every page I’ve ever written, I would probably take it. And every page would be a little different, even just moving a comma. One thing that’s a stark difference between this book and the others is that I didn’t feel like all of myself were in the other books. My sentiment, my sensibility, with humor, the calling of more pop culture and really using all registers, of lexicons and vernaculars, colloquial, regional speech. One of my heroes is C.D. Wright, and I’ve always been trying to write towards her capacious use of varying levels of dialects. That’s what I’ve always reached for. You know, like any debut — I debuted twice — there’s a lot of self-consciousness and uncertainty. After my mother died, I was just like, Fuck it. Everything I did was for her. When she died, I just felt I could do whatever I want, like what’s the point of all this. It was like swinging between two extremes. Either, it was just forget it, like, there’s no point in writing, or — it was during COVID — I was like everybody else; depressed and uncertain, and grieving. Personally, my mother died in November [of 2019], and COVID happened in March, a few months later. So I felt liberated. It’s a word that I don’t use often.

I noticed I wanted to showcase more of the New York School influence on my work, which has always been there. I didn’t have the confidence to really use it. I always wanted to start with the word “Hey.” It seems so clear to me. Hey, I’m here. Hey, this is a poem starting, a metaphysical plea or signal to say, We’re here together now. We’re in this room together. There’s a sort of intimacy and I didn’t have the shirts to do that. It took me however many years I’ve been writing — 14 or 15 — to finally do it. I feel all of myself is here, finally.

Time Is A Mother has that New York School pedestrian quality. Who are some of your queer influences, and any from the New York School specifically? Judith Butler, [James] Baldwin, [David] Wojnarowicz, Peter Hujar, and John Rechy. [James] Schuyler from the New York School. Amiri Baraka was also part of the New York School — he’s been whitewashed. Of course [Frank] O’Hara, [John] Ashbery. Then the second generation with Alice Notley, Bernadette Mayer, and Ted Barragan. Joe Brainard is probably the most prominent one because he has an innately hybrid impulse through and through.

The New York School is so directly associated with painting, and the downtown visual arts scene. Could you speak a bit about your relationship to visual arts? If I had more patience, I would be a photographer. I don’t have patience. I admire the work of Collier Schorr, [Henri] Bresson, Gordon Parks. I love Susan Sontag’s work on photography, and Roland Barthes, of course. Camera Lucida. The covers of all my books are photographic because I feel a very great kinship with photography in its ability to create a myth out of the real. You look at a photo, and anything you write about, it ends up being true, right? So the photograph because of how it’s framed is very seductive and capacious and ends up being to me a very queer form because it sets up what is seemingly fixed. As we interpret [photography], or as we contextualize it, anything could happen. For me, that’s the closest I see to my own work in ‘auto-fiction,’ or auto-mythology, which is how I view my poems. Taking the lived experience and then mythologizing it towards other tropes. My poems don’t tell about lived things. They set up lived scenarios, and then they turn them into something else. I think photography is really elusive in that way. It’s seemingly so static, and so finite. Every pixel, every frame is there, but the mystery is in the interpretation. I think if I were to look at my own work, it’s the perspective that is in response to the real, the large, ongoing photograph of living and lived experience.

Unlike the New York School, the poems in Time Is A Mother exist outside of the metropolis. How do you think about nature? It started in On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, and I’m trying to develop it further, this idea of queer rurality — what is queer worldliness if it does not depend on the metropolis to save it? What happens to those of us who can’t go to the city? The trope is that there’s this linear proportion in which the city is the salvation, and that if you can escape to the city, the narrative ends when you arrive. It looks so similar to what marriage is for straight heteronormative narratives. If you marry, the story’s over; The bildungsroman, when you either graduate, high school or college. I just felt like what happens if there isn’t a destination for a quick narrative? Which is why in On Earth there’s no triumphant finale. On Earth begins with this idea that the speaker has already finished college. So that the kind of spilling-back-into memorializes ruralness. I want to keep writing and exploring this idea of queer worldliness in nature and recalibrate it as something that we can take root in, and we might not have to always escape. I see that in my life. I’m a New Englander, and I don’t know if people are aware, but New England is mostly rural. I mean, you think about Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, even Massachusetts, in Western Mass. If I just put you in the backseat of a car and you’re just driving, it could look like Kentucky… including the Confederate flags. Most of my friends are farmers.

They’re queer farmers. I know a lovely couple who raise flowers, which is the gayest thing I’ve ever heard of. They took squash fields and turned them into flower beds. There’s a CSA run by a trans man. I think so much about what happens if we don’t leave, if we actually refuse total opposition, the project of opposition, and turn towards the project of alterity? What would happen? That’s already occurring in my community, and really inspired how I think about my work, and somehow the relationship with nature is usually a fraught one. Also, for a person of color I was indoctrinated in elementary school and throughout my education — when someone says hiker, archaeologist, conservationist, I don’t see a person of color. Or a hunter. Or a farmer. Meanwhile, these are things that establish civilization across the globe, yet in the American semiotics, we don’t see that. It’s often a white man in the propagandized symbols that we see consume. And so nature is very important to me, and it’s something that I’m still working towards, in my ameliorating it within the queer context.

OCEAN WEARS JACKET AND SHORTS BY BODE. ACCESSORIES THROUGHOUT, OCEAN’S OWN.

OCEAN WEARS JACKET AND SHORTS BY BODE. ACCESSORIES THROUGHOUT, OCEAN’S OWN.

Do you feel like there are clear differences between a queer rural community and a queer urban community? A hundred percent. In the rural community, the same faces come back. This is more about ruralness, rather than queerness. In ruralness we see each other more often because it’s smaller. The distances between us actually get collapsed. For example, if you’re just going to birthday parties for your friends in a rural community, you’re going to see everybody all the time in the same circle like 12 times a year, and that creates this real rich relationship where the conversation ends up going beyond, “What are you up to?” I’ve lived in New York for 11 years.

I went to school here and I floated around trying to cut my teeth as a writer, and I felt it was very thin, right? You see people less. You see people maybe twice a year at a reading or something. There’s so much to see and to do. Then the conversation is usually just these updates, but when I went back to New England, with a much more capacious way to live, I realized, “Oh, I want to live like this.” There’s so much more to this, and there’s so much more care, I think, because there’s so few of us. We know that when one of us is having top surgery, there’s a meal train, like we all gather around. And there’s something really unique, where it starts to feel like a village, it starts to feel, ironically, or maybe not ironically, like Vietnam, the way I grew up in Hartford, the way my ancestors still live in the village where everybody’s crisis becomes your own for the time being.

Now back inside of a rural setting, are you more or less protective over your queerness? I’ve never considered myself protective over [my queerness] at all. I want to think of it more as a quest, and I’m excited about how expansive it might be. I think for me, it’s about like, “What else?” I think that’s part of my refusal to move towards different pronouns, even though I don’t necessarily feel like a male in the traditional sense. What happens when you don’t depart a frame, but ask what’s in the frame to be more, right? In a way, it’s like looking at the photo and asking for it to come out, or forward or be more three dimensional. I think for me, that’s why, although I don’t always feel like a male in the traditional sense, the conventional sense, I insist on keeping he/him pronouns. I don’t want what has participated in it to be the last word because it’s been participated in so poorly. It’s also a destination for so many trans folks, this idea of maleness. I think that’s why we shouldn’t let heteronormative straight folks have the last word in this space. There’s an argument of just saying, “let’s forget about all that, and then move on.” And I think that’s valid, too. But I’m interested in this agenda, or this project of like, “what if we had to stay here?” Just like what if we had to stay on this planet? Like, if we can’t jump off the planet what will we do? How will we expand it? How will we complicate it? I think for me staying in this same space and expanding its possibilities, in that sense, I don’t know if [my queerness] is protected, as much as deeply invested, curious. I don’t want to see my identities as things that are concluded. Anything that I present to the world, I don’t think it’s finite. I’m always learning more about it. Every living day.

There’s a great line in the new collection: “It’s hard to tell gender / from breathing.” Do you think poetry is gendered? It’s so gendered. It’s so gendered, and it shouldn’t be. A lot of my heroes, Denis Johnson, Raymond Carver, [William] Faulkner — It’s always the men who turn back at their poems and say, ‘That’s juvenilia’ as a way to code it as to say it was childish and thereby feminine, dreamy, flowery, decorous, frivolous, and thereby should be discarded, or in other words, ‘I moved on from that.’ I think poetry still has this gendered position in the mainstream approach, but also in literature. Even amongst its practitioners, even amongst its best practitioners. I’m sick of it, but what can you do? When men have dominated the conversation for so long, you see their fragility is deeply embedded. Homophobia and misogyny is telling them that they should divest themselves of this very important thing because they’ve gendered it. It should never have been that way, but they did. And then you see poetry as this sort of childish, whimsical affair, not in the real world, right? And the real world is also gendered. The real is the male work, right? You’ve probably met so many straight men who say they only read nonfiction. This is the idea of the the quest of nonfiction, which is by the way also fiction. History, rendered in the sentence, is a fictional project, depending on who’s telling it. But there’s this kind of mythos that if you read the truth, then somehow you’re performing more of your masculinity.

Are you feeling like you need to address these things when you’re writing? No. Sometimes I feel like I should say so, but I don’t because poetry is so much more than that. As an artist, I’m interested in not turning my art into purely an oppositional project because when you’re always in opposition, you always speak second. You’re always responding to the failures of the imagination of hegemony. I think in that sense you’re then perennially subordinate. I think when it comes to creativity, this is our one shot to create something on our own terms. I’m more interested in alterity. But that doesn’t mean I don’t address the things that matter to me, the things that are killing us. But I don’t go on saying it’s my job to correct straight people because then my job as an artist is maligned. I take myself actually out of the scenario as a maker, and I can’t do that. I’m not interested in saying, “I’m here to do XYZ because XYZ people are ignorant.” If I do that, I’m like the maid of your own knowledge. And I’m not anybody’s maid.

As a Vietnamese person in America, as a queer person in America, as a writer in America, do you yourself ever feel dangerous? I don’t. I want to say yes, but I don’t. I feel very small. I’m only Ocean Vuong when I’m legible in context. I’m Ocean when there’s the program, when there’s a stage, when there’s an interview, when there’s an introducer, and a podium, but when I go out, I’m a chink. I’ve experienced that all the time. I get an ID for the college where I’m a professor, and the woman says, “Well, you don’t look like a professor.” I think it’s important for me to articulate that, in certain realms, I’m this big thing, but in the majority of the world, I am still seen first as an Asian body, in the optics and all of the misinterpretations are mounted on that semiotic structure that I can’t escape. It’s interesting too, because I see people change. I go into certain rooms, and when they know, when I’m introduced, I see the way people physically, invisibly, change the way they speak to me. I’ve been to parties where they thought I was the waiter until I was introduced as the speaker. You know, and then all of a sudden, there’s this kind of… it’s like that math lady meme.

I don’t feel dangerous at all. I feel powerful, when I’m at my best. Sadly, I feel most powerful at my best when I’m, you know, in my room at my desk. I feel most powerful in front of the page, but I don’t feel dangerous, at least not yet.

OCEAN WEARS VEST BY AMI, SHIRT BY A.P.C. AND PANTS BY DIOR.

OCEAN WEARS VEST BY AMI, SHIRT BY A.P.C. AND PANTS BY DIOR.

OCEAN WEARS SHIRT AND JEANS BY COMMISSION, TANK TOP STYLIST’S OWN, UNDERWEAR BY SAVE KHAKI.

OCEAN WEARS SHIRT AND JEANS BY COMMISSION, TANK TOP STYLIST’S OWN, UNDERWEAR BY SAVE KHAKI.

Ocean Vuong photographed in New York City. April, 2022.

This story was printed in GAYLETTER Issue 16, get a copy here for the full story.