ILLUSTRATION BY NARUKI KUKITA

STEPHANIE YOUNG

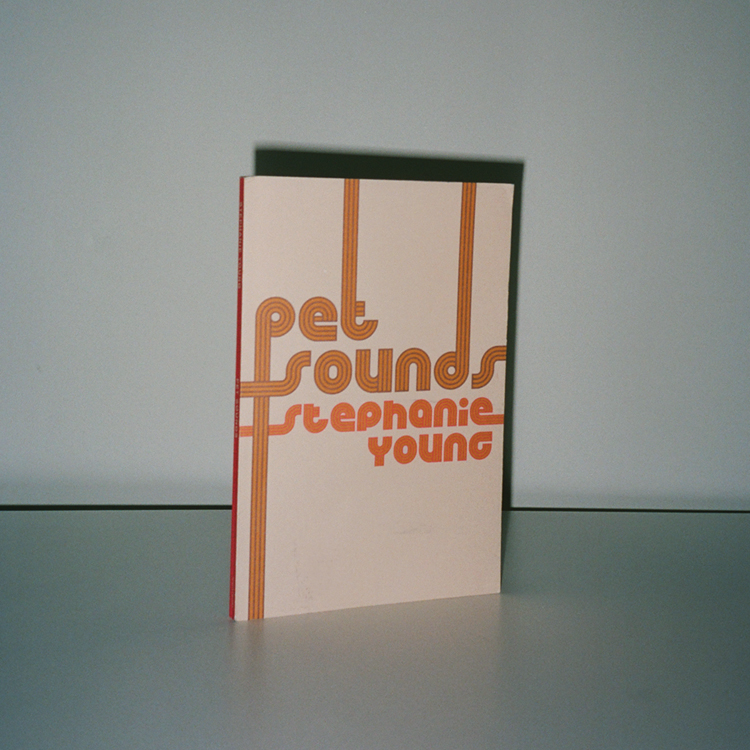

On a late summer morning, we called writer Stephanie Young to talk about her latest book of poems, Pet Sounds, and about her scholarship on disparity in contemporary American poetry. What follows is our conversation alongside an excerpt from Pet Sounds, the poem “IN MY MEME.” Meow.

Trying to be a good researcher, I listened to Van Morrison’s song “Madame George,” the original take from his album T. B. Sheets, referred to throughout Pet Sounds. It was cool to hear all the voices intermix and interrupt. What drew you to writing your version of “Madame George?” I have a group of friends who get a place in the summertime to write together. Revising and revising. I was driving home from that retreat, it was in the days past CDs and yet my car still had a CD player. I had that album [T.B. Sheets] in the car. I put it on and it did that kind of Proustian thing, opening up a wormhole into the past. It opened up a history, an autobiographical story that I wanted to tell. This complicated story about being bi, and about not wanting to ever claim that because I live in a relationship that’s recognized as a cis-hetero couple in the world.

I was listening to that song and remembering arriving in California. That summer, there was a dryness in the air. It was probably a fire season moment. I remembered arriving in California 20 years earlier. Music holds the past; it holds these moments up. And then it opened up. I couldn’t stop listening to the song. I went on a serious bender.

This is a way that poetry feels related to the essay form for me. Once I started listening and had that moment of encounter that felt almost mystical or something, I’m like, “oh, research. What have other people said about this song? What are the material conditions that produced this song? And what can I learn by looking at them?” Then, it’s like all American history. You touch it and it’s pure injustice, inequity, and bullshit. Like heterosexuality, or the couple form. You touch what feels intimate and what you find behind it is a property relation. The song became the vehicle for all of that.

So much of Pet Sounds felt like how, when you’re in love, you’re not just who you are right now; you’re who you’ve been for so long. And “nothing fits,” to quote another poem. That sounds like that queer relationship to the ex, right? It’s this large community.

The whole community is exes. I’m like, that feels right. And how does one think about a present cis-hetero relationship on the continuum of one’s past? Or one’s own relationship to queerness. It was uncomfortable for me to suddenly be like, “I’ve written this book about bisexuality,” even though this is something I’ve always really wanted to think through. It felt really hard to do. One of the big things that kept me from it was not wanting to claim a type of space. This is all very normal bi stuff.

The term is almost taken as a joke, but honestly, last night I was thinking as I fell asleep, “I’ve committed bi erasure.” It makes sense that that’s a common experience, but feels perplexing to try to describe to others. It is hard to take that term seriously when you think about the range of things we’re up against. It’s interesting to the extent that it’s some kind of symptom of limitations in thinking around sexuality that we still live with. I’m more interested in how those things are connected to larger problems. Like, you track it long enough, and it is connected to the atomized social relationships that keep us separate, in terms of the family unit or compulsive heterosexuality, which are all major problems connected to capitalism, which is what’s killing us. I’m interested in the kind of long stoner thought that leads me there. My personal experience of bi erasure doesn’t need to be taken seriously.

Thinking about the impetus for the book, have you read that Alice Notley piece, “Disobedience?”

No, but I’m writing that down. Alice Notley and Bernadette Mayer were my major influences coming up as a poet. Some of the main questions in “Disobedience” are “What is the thing that can’t appear in poetry right now? What is the thing that’s not being written about?”

I think I was trying to write a book that was about a relationship to queerness, to bisexuality, that was much more about discomfort with the category. I wanted to write against narratives of visibility or easy identification with the category, if that makes sense. I don’t know how much I’m reading about “nothing fits,” “nothing feels right.” We’re in a moment where there’s a category for everything.

The first poem in the long section, introducing the kitten concept [“in the dark i say you are a kitten / and I am a kitten and this makes us / homosexuals. it isn’t true”], also includes these lines: “what is a kitten anyways? / a younger woman who dates older men / something we have done / stout, furry, gray and white moth” The gesture toward intergenerational experiences resonated. In that moment I was thinking, what does it mean that my person and I are both bi? He’s older than me, but he’s dated men who are older than him. Something about our experiences of queer sexuality are wildly different from one another’s, and yet they also become a correspondence point between us. There are weird moments where I’m like, “Sometimes I feel like I’m a gay man with you. Sometimes it feels like you’re my girlfriend.” As much as we move through the world as a “straight couple” (with all the ease and lack of harassment that comes with straightness), in the intimacy of being together, I suddenly feel like I’m in this topsy turvy moment. It doesn’t feel straight at home.

I appreciate the book’s willingness to not cohere by the end, to not resolve, or become an answer. The last line of the book is “I’m learning to tell the difference.” I feel like that’s important in unmaking the systems we’ve inherited. We [Stephanie Young, Juliana Spahr, Claire Grossman, and I] just had an article come out in ALH [American Literary History] called “Literature’s Vexed Democratization.” Part of it is the anecdotal story of coming up in a moment when technology was making it possible for more and more people to publish. We really felt like this was a good thing.

Suddenly anybody could enter. The literary could be whatever you wanted it to be. What we have now, on the opposite side of what we thought would be a democratization, is a closing and a narrowing of the field. There’s a narrowing of the field stylistically, and paradoxically one of the ways it’s done is by allowing in some things that are different, both formally and in terms of demographics. The prize system can therefore show itself to be this rich, diverse place, yet we keep struggling against the traditions that have been carried forward, the approaches to who gets to be a writer. The wider the field gets, the more things get published, the more the prizes become a sorting mechanism for attention.

My first workshop teacher was Richard Wilbur [the formalist poet, 1921–2017], so I showed up at the MFA locked and loaded, ready to be a formalist if I had to be, but I thought it’d be more open. I experienced the weirdness of mutually exclusive ways to be rewarded for assimilation. To one direction as a gay writer, or the other as a Puerto Rican writer. Around that sticking point, what it means to be assimilated into the system, there’s this Claudia Rankine quote: “The notable difference between Black excellence and white excellence is white excellence is achieved without having to battle racism.” What it looks like for a Black writer to be assimilated into the system is very different. For the various identities that are not white cis men, incorporation into the system is attended to with various kinds of harassment or racism. The system is not in any way set up to have real conversations. It’s a voracious system that wants to eat difference. It wants to do that in very codified ways.

There are certain narratives it wants to uphold. There are other narratives it doesn’t want to hear. It does want the work to take certain kinds of forms. For anyone who’s making work that isn’t the specific narrative around your identity that the system wants to eat, it’s rough.

Very rough. I felt like a test case, or a pH strip. You used the term “Proustian” before: I always think about The Captive and The Fugitive [volumes of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time where the narrator traps his love in his apartment], and I very much feel like poetry is currently a captive of academia. One hundred percent.

Poetry is a captive of many things right now. It’s especially a captive of various national narratives that the U.S. wants to tell about itself. And the way that the Academy wants to repeat those things. A lot of the moment that we’re in comes out of that mid-century control over places where things like the Academy of American Poets and higher education overlap. That’s bonkers that you studied with Wilbur.

I had a semester as his student, and then a semester as one of his drivers. How old was he when you were doing that?

Yo, he was ninety-three when I met him. And ninety-five when I was driving him. Woah.

Yeah, that’s its own mess… It was a pleasure to talk with you. I’ll see you on the Internet.

Photo by Abi Benitez.

Photo by Abi Benitez.